Artist Blog

Every week an artist whose single image was published by Der Greif is given a platform in which to blog about contemporary photography.

Alexandra Davies – Interview

Mar 02, 2015 - Andrei Nacu

Alexandra Davies – Tabula Rasa »The project draws upon a collection of personal and found family photographs of siblings dressed in identical outfits to explore themes of identity, memory and absence within the family history. An attempt to restage these historical photographs in a contemporary context has led to questioning the relationship between mother and child and also the realisation of the importance of clothing in relation to certain memories. In venturing to recall memories from these photographs a certain overlap of fiction, which seeks to complete the gaps in the narrative has been identified and the addition of short stories to accompany the found photographs question the reliability of the photograph as a tool for recollection. Being highly aware of the weight of history which the collected family photographs held and their intensely personal nature she attempts to isolate them from their true identity in order to create a new imagined history for them. It is human nature to draw upon our own experiences in order to connect with the unfamiliar and the text integrates fragments of truth from conversations with those who have donated photographs with elements taken from literature, cinema and the artist's own imagination.«

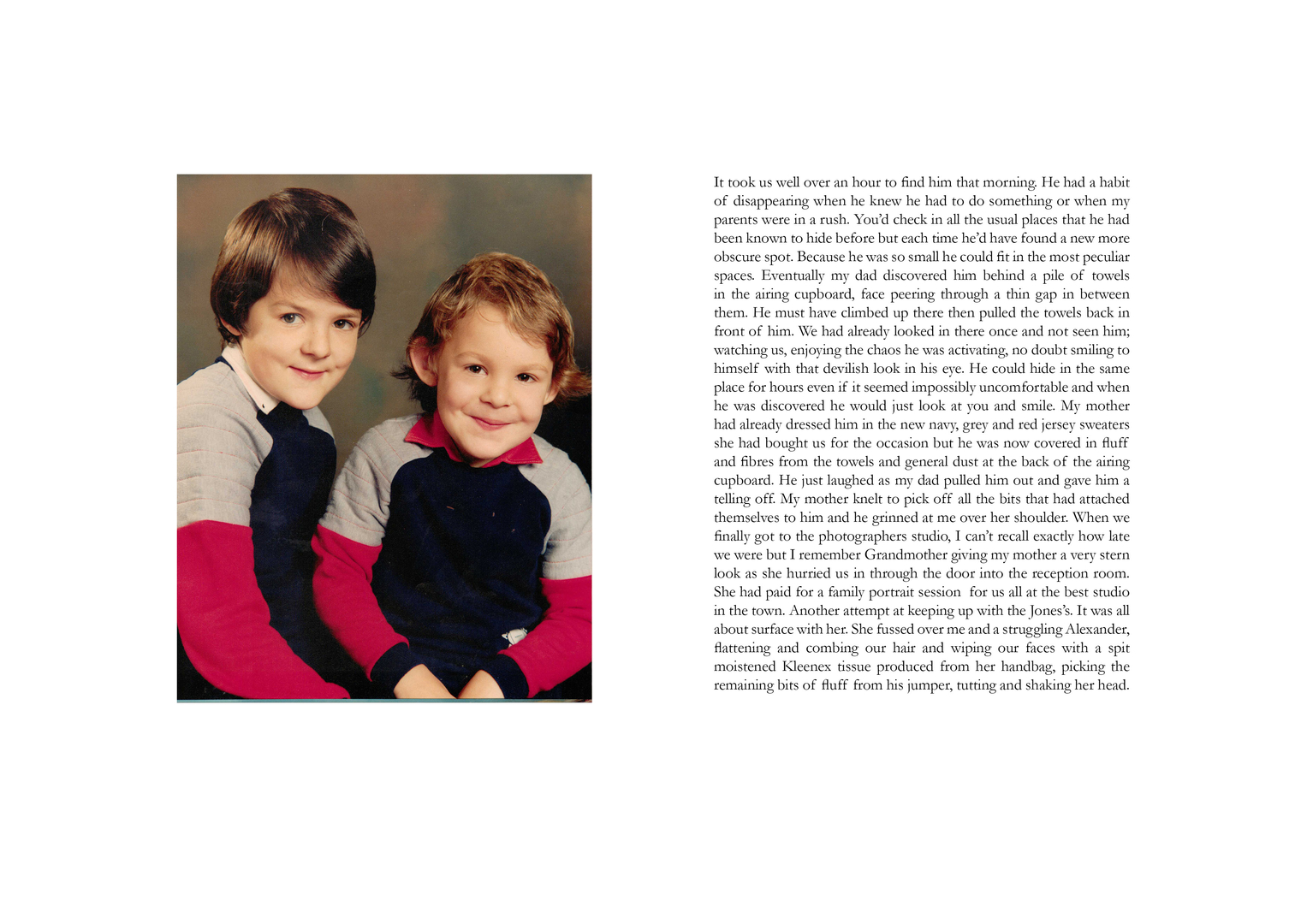

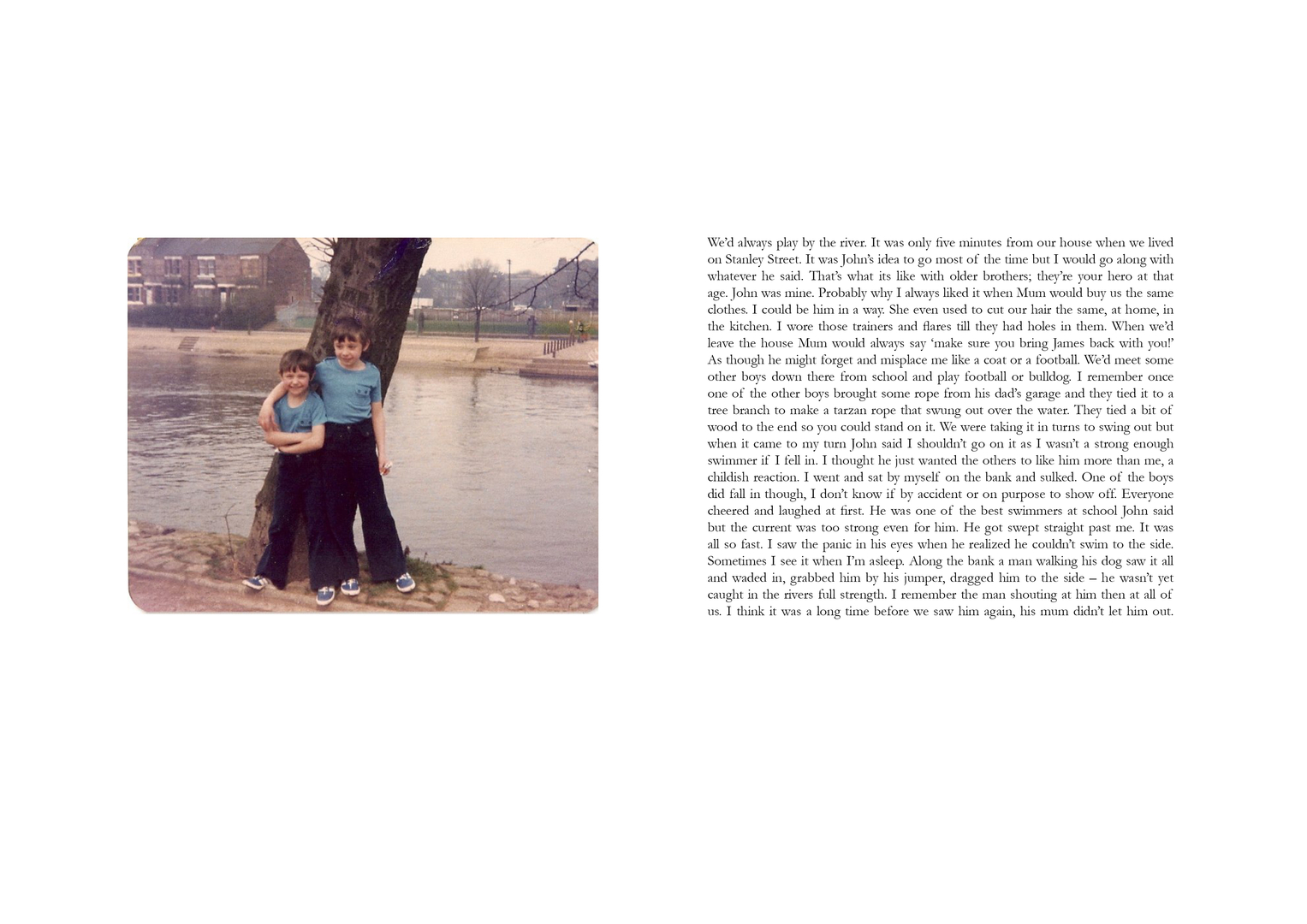

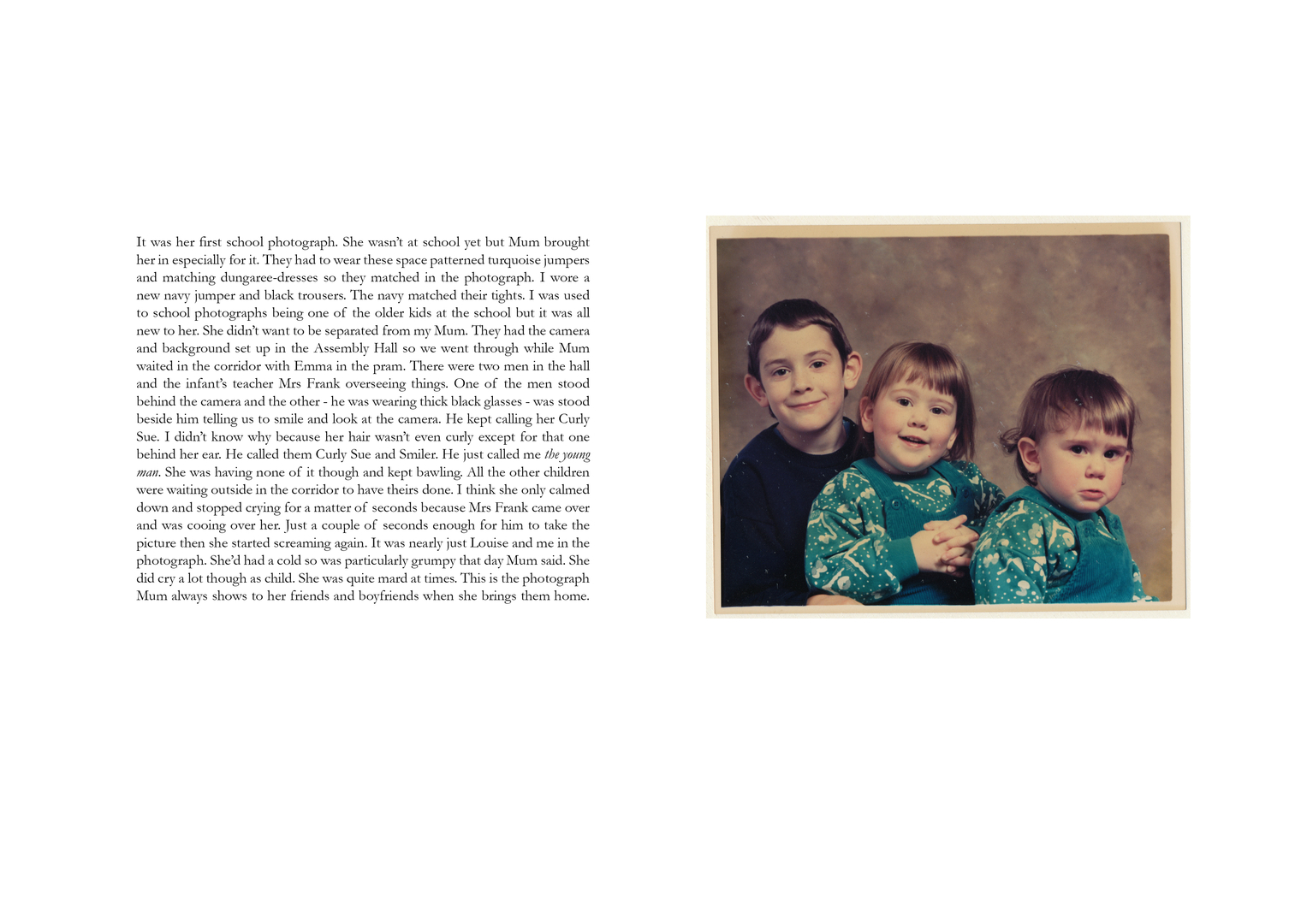

If in your earlier projects your practice was concentrated on creating your own images, with "Tabula Rasa" you work more as a curator and writer. How did you become interested in the family album and collecting family photographs and how has this interest evolved? I have always been interested in the family photograph and its ability to say yet at the same time withhold so much about the family sociology, the dynamics and relationships within a family structure. Beyond all other areas of photography I believe the family photograph has the strongest connection with memory, identity and loss and these were all themes I was trying to explore within the project. At the beginning of the project I would visit my mother’s house and look through her vast collection of family photographs; some arranged in albums, others loose or still in the sleeves that you’d get from the processing lab. Looking through them, I was struck by how often my mother would dress my two sisters and I in identical outfits. It would mostly be for special occasions; family get-togethers, birthday parties, holidays and almost always for school photographs. This got me to wondering why she would do this and whether it was as commonplace in other families as I thought it may have been. I collected together all these childhood photographs of my sisters and I then decided to put out a few online requests and ask people I knew if they had any similar childhood photographs they could send me. I built up quite a collection of these type of photographs and found that people would often send them accompanied by an explanation of what this occasion was, who is in the photograph and how their mother would do this kind of thing too, which I found interesting. It was like they wanted to share the story of that image with me, not just send it without any context. As a response to the material and to try to explore some of those ideas I started to do some staged studio portraits, which attempted to mimic the style of the school photographs with my two sisters. I got my mother to select an identical outfit for us, which we wore in the shoot. The portraits seemed peculiar and I wasn’t really sure they were working how I would have liked. They didn’t match up to my collected photographs and I didn’t feel it was really going anywhere. I think in terms of the process though I needed to try it and it may be something I return to in the future. It seemed to make more sense to focus on the material I had gathered and the importance of memory and narrative within the photographs. In the context of working with found photographs, making them open to new interpretations and narratives, what are your thoughts on ownership and authorship? At times I did struggle with this issue as these photographs were so personal to these people - they represented their childhoods and held their memories – and what right did I have to force upon them my own narrative and present it back to them and to the world? It helped to look at what other artists working with found photographs had to say on the subject as this aided my anxieties when it came to the process of changing the context and narrative of the images. In an interview I watched with British artist Mishka Henner he talks about all imagery being raw material, just as the streets and the world are raw material for photographers. The way in which you use that material to communicate something else is what is important. He likens it to how we do not own the words that come out of our mouths but the way in which we structure those words gives us ownership over them. That sentence has always kind of stuck with me. Also, I think because I had the blessing of the people who donated their childhood photographs I did feel a certain freedom to use them as I wanted. I would pick details from the email conversations I had with those people and then add my own fictitious twists to the narrative. It was a kind of reflection of how memory is often adjusted to support the photographic document and how it is human nature to apply our own imagined narrative to a photograph. Inspiration for the narratives would come from my own childhood memories, bits from books or films and from stories retold by my mother and other family members – I developed a kind of magpie-like collecting of all these memories which then filtered into the stories. I think the knitting together of the ‘true’ memory with the added fiction or borrowed memories seeks to compromise on the ownership and authorship. There are several artists who use found images in their works. How do you see your approach in this broader perspective? I think many of the artist who use found images work in a very conceptual way as it is about the process of taking something out of its original context and presenting it back in some altered form. The purpose of using found imagery, in my opinion, is that you have something to communicate about it otherwise why use it? Artists work with found images in numerous ways – be it Sherrie Levine’s rephotographing of Walker Evan’s American depression-era photographs (in After Walker Evans, 1981), Mishka Henner’s altering of Robert Frank’s The Americans photographs (in Less Américains, 2013) or Julie Cockburn’s reworking of old portrait photographs found in thrift stores – and all do so to make some kind of statement about the original image or what it represents. Although I did experiment with altering the physical found photographs, I think the addition of the text, presented as the same scale as the original photograph presents a kind of commentary without interfering with the images themselves. The text undoubtedly alters the image yet the original appearance remains in tact. Family photographs function as retainers and triggers of memory yet sometimes they are not the most reliable alias against forgetfulness. In your quest to recall memories from these photos you overlay a fictional layer over the stories learned from their owners, seeking to complete the gaps in the narrative. How do you draw the line between fact and fiction and how important is the truth in your work? All memories have elements of fact and fiction even in the first person recollection. Each person in a photograph will have a different recollection of the event or moment depicted so it can be impossible to identify the ‘true’ memory. Over time a memory can alter – details can be forgotten or changed to create a more interesting narrative or provide a happier or more flattering account for its subject. Individual experience at the time or since the photograph was taken can also contaminate our recollection of the original event and the retelling of the story by other parties can make us remember something differently. It was all these variables and uncertainty that I found so fascinating and I wanted to highlight these ideas through writing and presenting these fusion narratives. You give a new life to these images, loading them with a new meaning that was never intended when the photograph was being taken. How did the people in the photos respond to your augmented version of their memories? I think once they were aware of the concept of the work and what I was trying to achieve they understood that it was not me trying to sabotage their memories or anything like that. I think people were interested to see what narrative I had drawn out of their photograph. One of the photograph/stories was of my mum and 3 aunts taken on the seafront and there is a bit about them going there in my dad’s old car so when my dad read that the only incorrect detail he picked up on was that I had got the make of car wrong which made me laugh. By making each text precisely the same size as the photographic print you bring into discussion the complex relationship between memory and photography and how a picture can sometimes alter our memory in order to fit in with what is shown within the photographs. How did this decision affect the process of writing the stories? I would often write a draft of a story based on the extracted details and my imagined history for the image without thinking too much about the spacial restrictions of the text as this was before I had decided to arrange the text and image in that way. I was just writing the short stories relatively freely at that time. When I decided it might be interesting to present the text with the same proportions it did make it more difficult as I had to try to edit these stories to fit within those boundaries. I was working to a book/novel scale, as it just seemed to suit that format so the text size was small and I tried to use a uniform size and font for all the stories. During the editing process bits of text had to be removed, moved around or extended to fit within those very rigid restrictions. It seemed very apt though as I just thought how similar that process was to the way in which memories are altered in recollection or to support what we see of an event, person or place in a family photograph. The photograph never lies, or so we are led to believe, and human memory is so unreliable in comparison. I think it's great how you managed to cover most of the typologies found in the traditional family album, from studio portraits and school photographs to snapshots with holidays, birthday parties or daily life. What were your strategies in curating the photos and in writing the texts? I think much of the decision-making in the curating came from the material I received. There were some absolutely fantastic outfits and photographs that I knew I just had to use – they are just great photographs. They had so much to say about the period in British culture they were taken in terms of gender, class and the role of the family – I was fascinated by them. I tried to give a good representation of all those occasions where the identical outfits would be worn, and looking through the collection it became apparent just how much a part of family life it actually was. I guess I selected the ones that I felt had a good visual impact and that weren’t so similar to others I was using and also the ones that I thought had a strong sense of narrative, something that interested me (the puntum as Barthes describes it). In most of the cases the siblings are children, dressed up identically by their mothers, yet there is the story of Gloria and her sister, who decided themselves to have the same dress. Why did you feel the need to include this situation from outside the mother-child relationship as well? I wanted to represent the different situations where siblings may have been dressed the same and indeed in some cases it may not have always been the mother’s decision. There were often other reasons why it occurred; sometimes children wanted to dress the same or in many instances it would be the cost of new clothes at the time. That photograph was taken in the 1960’s and the siblings in it were from a family with six children so being able to afford new clothes was something of a luxury. The sisters got around that by buying some material together and making their own dresses. I just felt it was an interesting story and wanted to include it as a little bit of social history. Working at this project was also a process of self-knowledge and re-evaluation of your own memories. How much of your own childhood is reflected in these photos and in their new stories? I think whenever you look at a photograph you tend to apply your own experience and knowledge in order to read and relate to it so it was quite natural that some of my own childhood memories or even memories of films or books or stories I had heard should manifest themselves in the stories. It is in no way trying to be autobiographical. It was more a process of borrowing these bits of memory, bits of narrative in an attempt to make comment on the relationship between photography and memory and how memory is constructed. Obviously the photographs I included that are from my own childhood are more personal but even these have been altered in the reconstruction. I showed my two sisters, brother, mother and father the same photograph of the three daughters/sisters dressed identically with my brother and asked them all individually what they remembered, if anything, of the photograph. This small experiment was enough to observe how different people’s recollections of the same photograph can be. Some details matched, others did not, and some could not recollect anything of the day and were using the photograph to give them clues. It became a jigsaw I had to piece together from these varied recollections.

British photographer Alexandra Davies was born in Crewe, 1987. She completed a degree in Photography with Fine Art: New Media at the University of Chester and a Masters in Photography at Manchester School of Art. Her work has been exhibited at Guernsey Photography Festival and at several shows in Manchester. The work she creates focuses largely around ideas of the psychological landscape, in particular the idea of the »inner space« and are to the eye somewhat aesthetically pleasing, beautiful even, with a sense of underlying melancholy. Her current practice explores family photography and the complex dynamics of female family relationships, focusing in particular upon Mother-Daughter and sister relationships using found photographs and generating new work from these.