Czar Kristoff

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

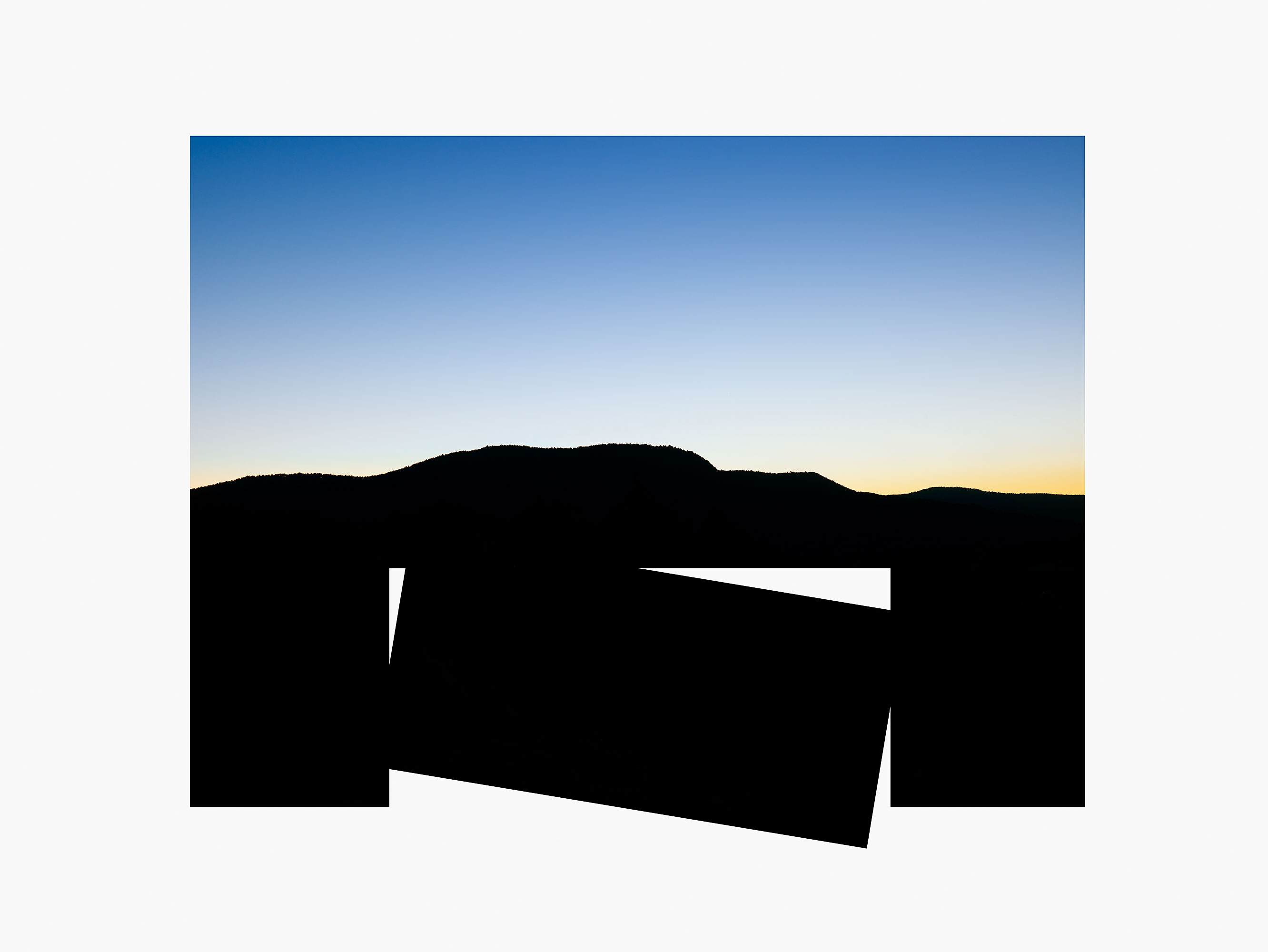

John MacLean - Hometown

Sep 30, 2015

HOMETOWNS Artist’s Text by JOHN MACLEAN Artists’ biographies frequently concur on one point: their subjects first awaken to the idea that they may be able to make art when they encounter the work of an established artist. That is, most artists are converted to art by art itself. This first creative affiliation encourages the fledgling artist’s latent ambition and bolsters their self-belief; it may then be supplemented with others, forming a network of mentors-by-proxy within which the burgeoning artist begins to articulate their voice. Peruse the book collection of anyone with a serious interest in art and you will find a similar network here too — an inner circle of ‘desert island artists’ represented by the most-thumbed books on the shelf. Whilst a prevailing aesthetic may be evident, any suggestion that the relationship between the viewer, the image and the artist is just a mutual appreciation of formal values is to deny that artists are able to tap into something that runs much deeper. One could speculate that good artists act as conduits, putting the experiences of their lives into their work. Great artists are able to put something of themselves into it as well. These are underlying qualities, but they can often be recognised by the viewer, whether consciously or not. So if art can explain the artist, I would suggest that the art we surround ourselves with explains something about who we are, too. The qualities we admire in an artist, which we ‘know’ through the emotive function of their work, are the qualities we value, or aspire to, in ourselves. If paths run through people as surely as they run through places, the art we revere represents a crossing of the artist’s paths with ours. Unsurprisingly perhaps, if the developing artist becomes aware of a stylistic junction with their mentor, their instinct is often to cover their tracks rather than explore the common ground. This is the ‘anxiety of influence’ that has created avant-garde movements in art, most apparent in Modernism’s ‘fear of contamination’. If the quest of the artist at this crossroads is for a truly innocent gaze, it will always be out of reach: motifs in art exist throughout human history and across cultures, supporting the concept that we are born with a foundation of shared images — a collective unconscious of archetypes. Artists evolve by absorbing what they need at any given time, from any given place. They collect and refract into their art a spectrum of influences through their own prism of insights and limitations, eccentricities and obsessions, certainties and vulnerabilities. To take one example, Peter Fraser does not flinch from the creative influence of William Eggleston, nor Eggleston from Cartier-Bresson, nor Cartier-Bresson from Degas, nor Degas from Manet. In each case the artist has an innate personal vision strong enough to prevent their art from being inundated with influence, but equally knows that embracing its intertextuality prevents their art from stagnating. They absorb existing ideas, re-energize them, make them new, and pass them on. Artistic influences may be amplified or compressed as they pass through artists, but their passage through history is recorded in the open-ended volume we call tradition. Every image is constructed through inheritance and reciprocity; every image bears a lineage from previous images, and every artist a lineage from previous artists. Paradoxically, whilst the creative desire is always to look forwards, ‘original’ art is always, at least in part, an encoding of work from the past. Hometowns takes a reflexive look at this process of encoding. It began life as a line in my notebook: ‘Photograph the hometowns of your heroes’ — an idea for a layered investigation into the places which influenced those artists whose work has coloured my own. Two years later, that line has become a sixty-five-image, photo-homage to a unique group of artists who have been my own mentors-by-proxy, and an endeavour to untangle the strands which connect me to their work. In total, I have travelled to twenty-five towns and cities — the environments where ‘my’ artists each spent their formative years. Every trip was preceded by a period of biographical research, which inevitably refreshed my memory of the photographs, paintings and sculptures that emerged (at least partially) from these neighbourhoods. Important artworks had persuaded me to travel to these locations so, unavoidably perhaps, I photographed each hometown through their afterimage. But each place provoked an individual response, and I found myself swimming with and against those currents. Paying tribute to the spirit in which each artist worked was a central concern, but intrinsically this meant making my own imprint too. After all, to make works that were mere genuflections would have been an artistic betrayal. The key seemed to lie in the paradox of this series: that these photographs have been formed by a process of unravelling. So I have tried to find opportunities where I can add ‘twists and turns’ of my own to the photo-mechanism of re-braiding. Overall, I hope they have an underlying quality that reflects the ambivalence experienced by every artist: both the anxiety and ecstasy of influence.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Guest-Room Annekathrin Kohout«

»Der Greif #8«

Early Childhood Expeditions

Oct 04, 2015 - John Maclean

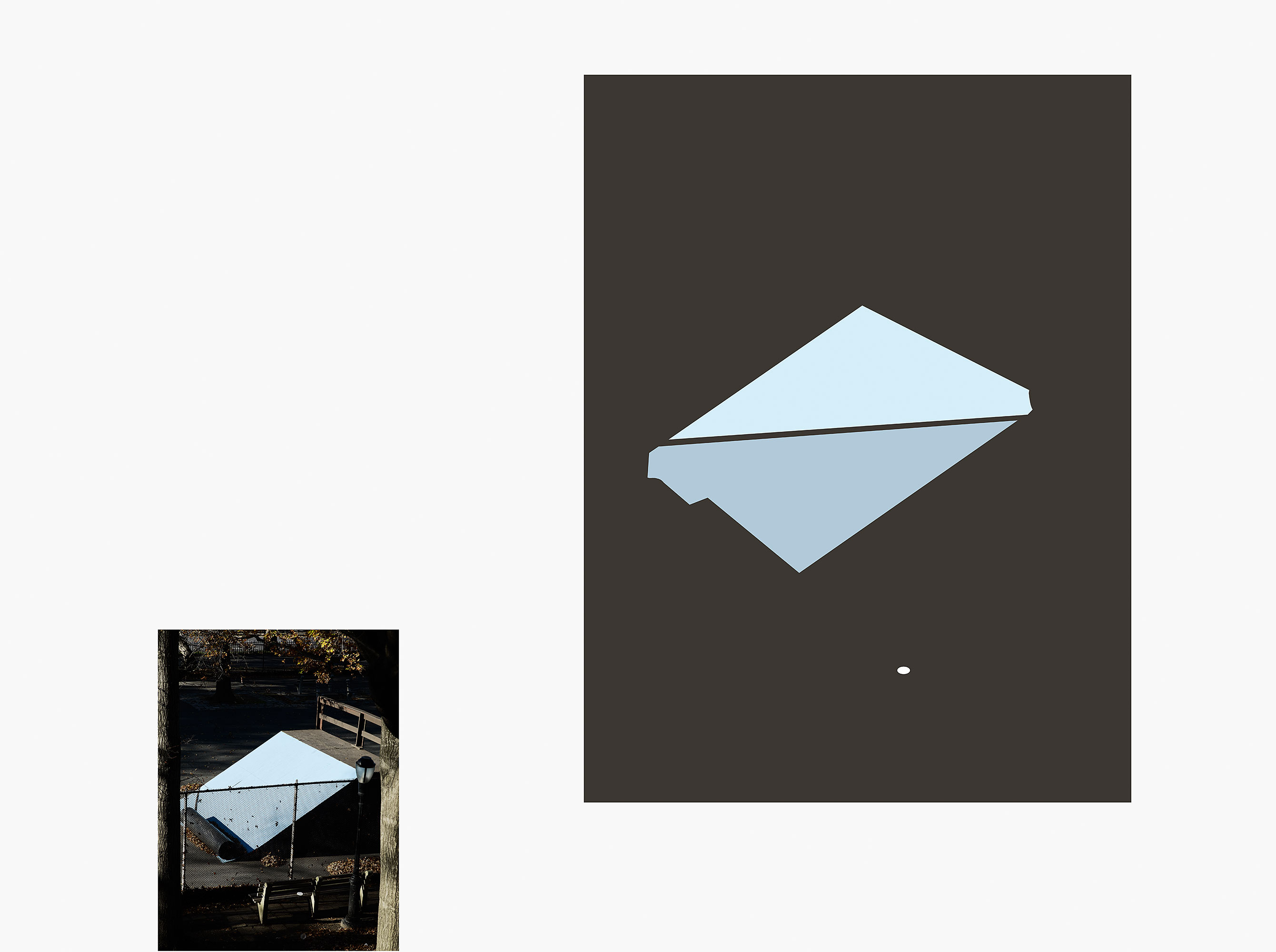

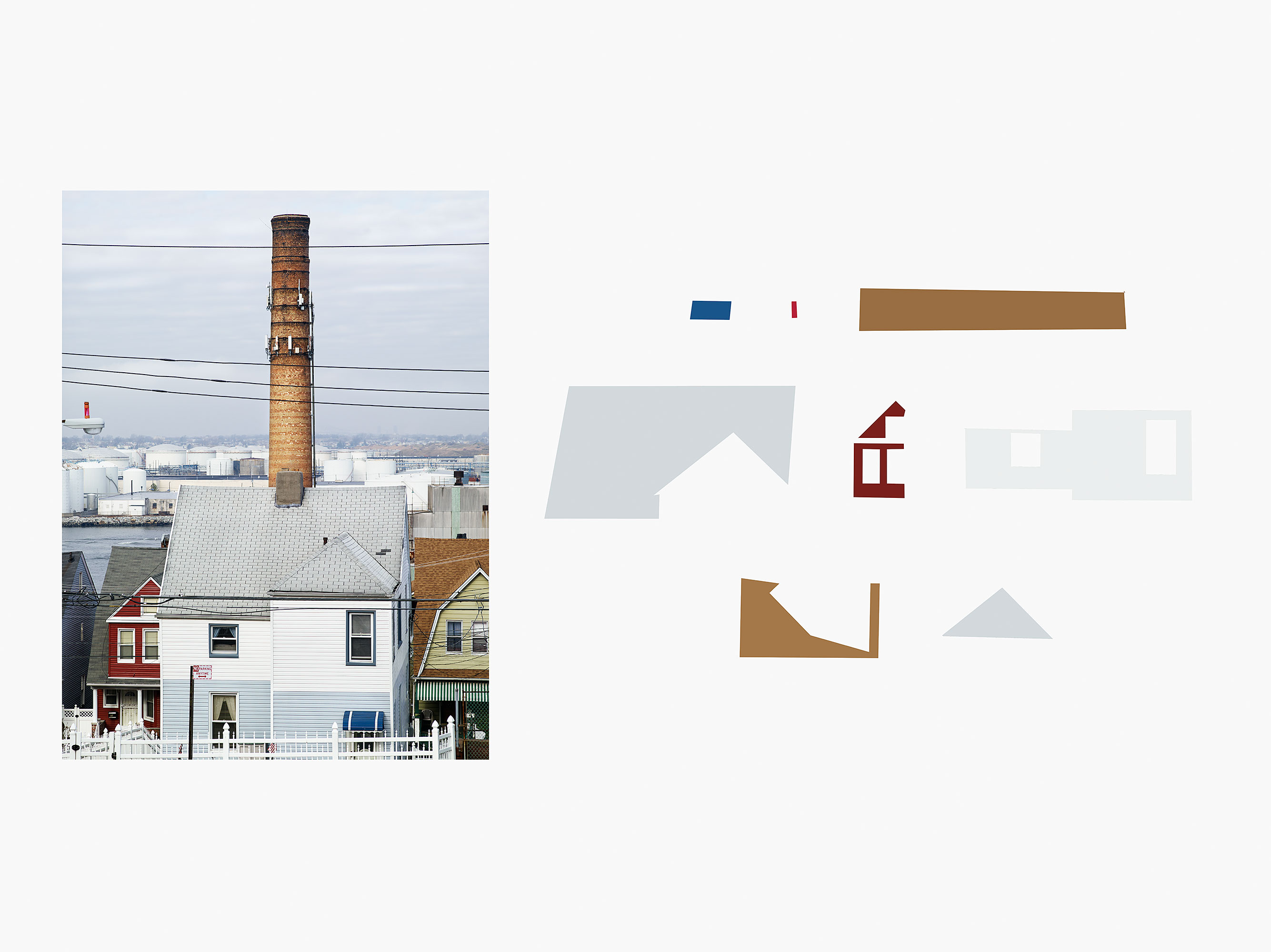

An introduction to a recent photographic project of mine: Hometowns. Showing at Unseen 2015. http://www.jmaclean.co.uk/ 'It is very difficult to know people… for men and women are not only themselves; they are also the region in which they are born, the apartment or the farm in which they learnt to walk, the games they played as children, the old wives' tales they overheard, the food they ate, the schools they attended, the sports they followed, the poets they read, and the God they believed in. It is all these things that have made them what they are, and these are the things that you can't come to know by hearsay, you can only know them if you have lived them.' W Somerset Maugham, The Razor's Edge, 1943. ‘Nothing is so well observed, nothing is so real, as what we see for the first time, in childhood, adolescence and youth’. David Bellos. ‘It is art that explains the artist’. Carl Jung. Introductory Text by Aaron Schuman 2015 Several months ago, my wife and I allowed our son – then nine-years-old – to wander out the front door and down into town, alone, for the first time. It began on a Sunday morning, with a mission to get a pint of milk from the nearby shop. With change in hand, he tentatively meandered around the corner and out of sight; a few minutes later he returned triumphant, literally jumping with excitement. In the subsequent days, many more journeys to the same shop followed – for butter, for sweets, for whatever he could think of that would get him out on his own for a little while. And then his territory began to expand rapidly, to the park, to friend’s houses, to the playing fields, the town center and beyond. As both his familiarity and confidence with his surroundings grew, I was struck by how much he relished his newfound freedom and sense of independence. I was also reminded of how, on such early childhood expeditions, even the most modest facets of one’s immediate environment – a street corner, a parking lot, a crooked crack in the sidewalk, a low-hanging tree branch offering access to its canopy – become pregnant with private meaning and purpose. As one begins to consciously consider and survey this vaguely familiar but nevertheless novel terrain for the first time, the boundaries of one’s own life, experience and understanding of oneself are expanded exponentially. And through the process of identifying and absorbing particular landmarks, contours and features that contain specific significance for oneself, one redefines and reestablishes one’s own idea of ‘home’, of its borders, and ultimately of one’s relationship with the world at large. Within a matter of weeks a child explores, and then absorbs, their surroundings in a remarkable way, not only defining it for themselves but then defining themselves through it – ‘the town where my home is’ becomes ‘my hometown’. In his poignantly observant body of photographic work, Hometowns, John MacLean pays homage to the incredibly subtle yet important influence of the hometown, particularly in relation to the fundamental visual development of artists themselves. Beginning with a simple idea that he quickly jotted down for himself in a notebook several years ago – ‘Photograph the hometowns of your heroes’ – MacLean has since explored and photographed more than twenty cities, towns and neighborhoods around the world, where a number of his artistic ‘heroes’ spent their childhood. From Moscow to Mexico City, from the south-west of England to the American Midwest, MacLean has traversed the globe not in search of its most spectacular monuments or most exotic landscapes, but instead in search of the everyday places that served as the most basic visual experiences and foundations for those artists who have inspired him, and thus for his own catalogue of creative inspiration. Extremely well versed in the works, approaches, practices and personal biographies of his ‘heroes’, MacLean is remarkably adept at visually tapping into each one of their childhood environments, and invoking the underlying role that even the smallest of details may have played within the young minds of great artists-to-be. A soft morning fog slowly evaporating around a radio tower that stretches high into the Californian sky invokes the ever-shifting heavens explored by James Turrell; a tangle of dirty rope and rusted wires lying across Moscow snow pays happenstance tribute to the serpentine brushstrokes of Wassily Kandinsky; simple and straight-talking signage seen throughout Oklahoma City - for softball, sound systems, and Chevrolet – quietly mimics the pop-infused imagery and deadpan aesthetic of Ed Ruscha; and so on. Yet beyond delicately echoing, referencing and reverberating with intimations of each of his ‘heroes’, MacLean’s photographs are strikingly original, visually arresting and deeply personal in their own right. In a sense, Hometowns collectively reflects MacLean’s own artistic ‘hometown’ of sorts, built of childhood stomping-grounds and populated by influence of those artists that he most admires. Like a child let loose into the world alone for the first time, MacLean carefully surveys, defines, explores and then absorbs his surroundings – in this case the territory of his own, personal artistic influence – but then expands far beyond it, mapping an entirely new and fascinating creative terrain, and redefining himself as a mature artist in the process. In doing so, he allows both himself and his audience to reflect on the notion of influence altogether, and then relish in the newfound insight, playful excitement, and remarkable sense of independence that such a freedom to roam affords.

The Grin without the Cat

Oct 03, 2015 - John Maclean

Photographs from a work in progress and some thoughts on their origins. When I was at school we were occasionally asked to supervise art classes for the younger children. I remember being intrigued by one child who would draw off the page and onto the table. Once, with a sheet of sugar paper in front of him, he painted onto it—then onto the wall—then onto the floor. He had no sense of edge. Watch how a child draws a house for the first time. The child draws the front, the sides and the back; then, perhaps he sketches the path leading to the tree and swing, and perhaps even then something that is inside the house. These elements are either drawn separately or jumbled up together. Looking over the child’s shoulder, the teacher or parent might say: ‘Oh no, you can’t see all these things at once!’. But in a sense the child is right in the first place. The child’s version is richer and more alive; the adult’s version is narrow and conveys less about the manifest experience of a house. In the 19th century, German pedagogue Friedrich Froebel encouraged the idea that the child should be an explorer of the world’s textures, laws and frontiers, who should be left to make his or her own discoveries through unstructured play. Froebel wanted children to ‘reach out and take the world by the hand, and palpate its natural materials and laws’. Early Froebelian kindergartens had few figurative toys. Instead of trains, dolls and knights, there were wooden cubes and spheres, coloured squares and circles, pebbles, shells and pick-up-sticks. Children spent their days singing songs and playing games, arranging the pebbles in spirals and circles, balancing blocks and picking up sticks. This open play was, as Froebel imagined it, the means by which ‘the child became aware of itself, and its place within the universe’.

The Idea of a Door

Oct 02, 2015 - John Maclean

imeo video_id="110168157" width="1000" height="563“] Some thoughts on Jacques Tati's film Playtime. Playtime, Jacques Tati's fourth film, bankrupted him. He built an enormous set just outside Paris employing hundreds of construction workers. It cost 17 million francs in 1967. To save money, many of the buildings in his film are, in fact, giant photographs — as are the 'extras' who populate background scenes. Tati's comic protagonist (Monsieur Hulot) passes through this constructed world — and his helplessness highlights this new world's absurdity. Playtime mocks concepts which director Tati disliked: work, efficiency, hurry, and organisation. Idleness in Tati’s films is not an absence of work, but a positive form of social behaviour, and a clear pole of value in the world of the film. Tragedy and comedy both deal in errors of perception and their unveiling. In Playtime there are no neat resolutions to close off Tati’s gags, no punchlines, no conclusions. Structurally perfect though they are, Tati’s comedy does not drive plots or make stories. Like John Baldessari, Tati employs humour for its ability to make the ordinary seem absurd and the absurd seem ordinary. A typical Tati gag structure becomes funny... through repetition and incremental exaggeration. Tati believed that if art isn’t playful, it’s nothing. He thought of play as being incredibly important and deeply serious. Unusually for a film-maker, Tati sought to use sound as a comic device. This required him to unravel the rules of natural sound, and to turn them upside down. He knew what the rules were and he learnt to play games with them. Sound in Tati’s films is material and materialistic. Each one of his films teaches us that the only way to get somewhere, anywhere, is by going astray. Playtime was a financial flop. In the original plan for Playtime silhouettes of the film’s characters would have been projected onto the walls of the auditorium, mingling the imaginary with the real, mixing viewers with the film itself. The last 15 minutes of Playtime immerse each spectator in a personal solitude. Then it asks that the audience walk out of the cinema back into reality. It is possible that such an ending is responsible for the film’s failure to connect with the public. Jacques Tati is David Lynch's favourite film-maker.

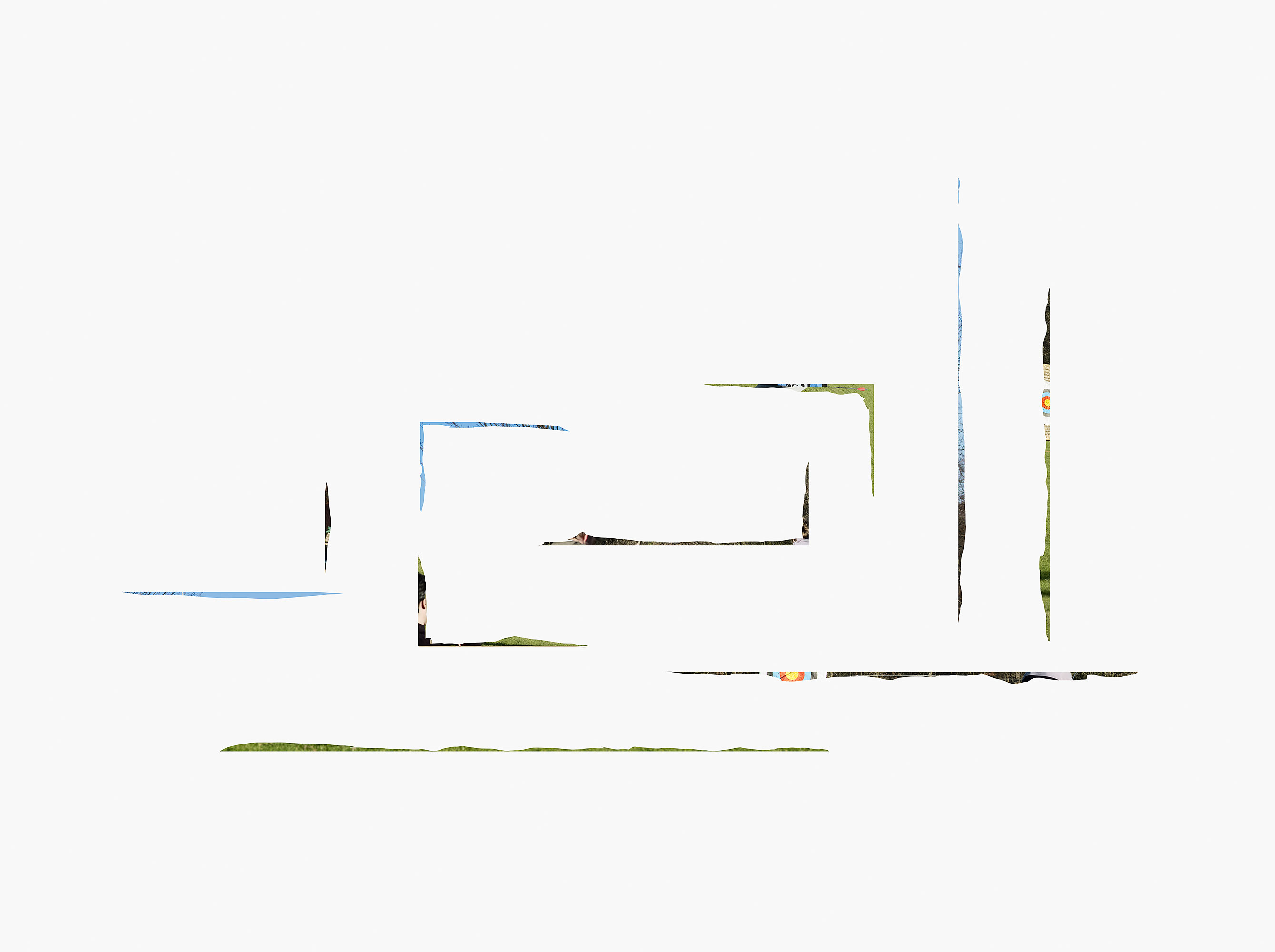

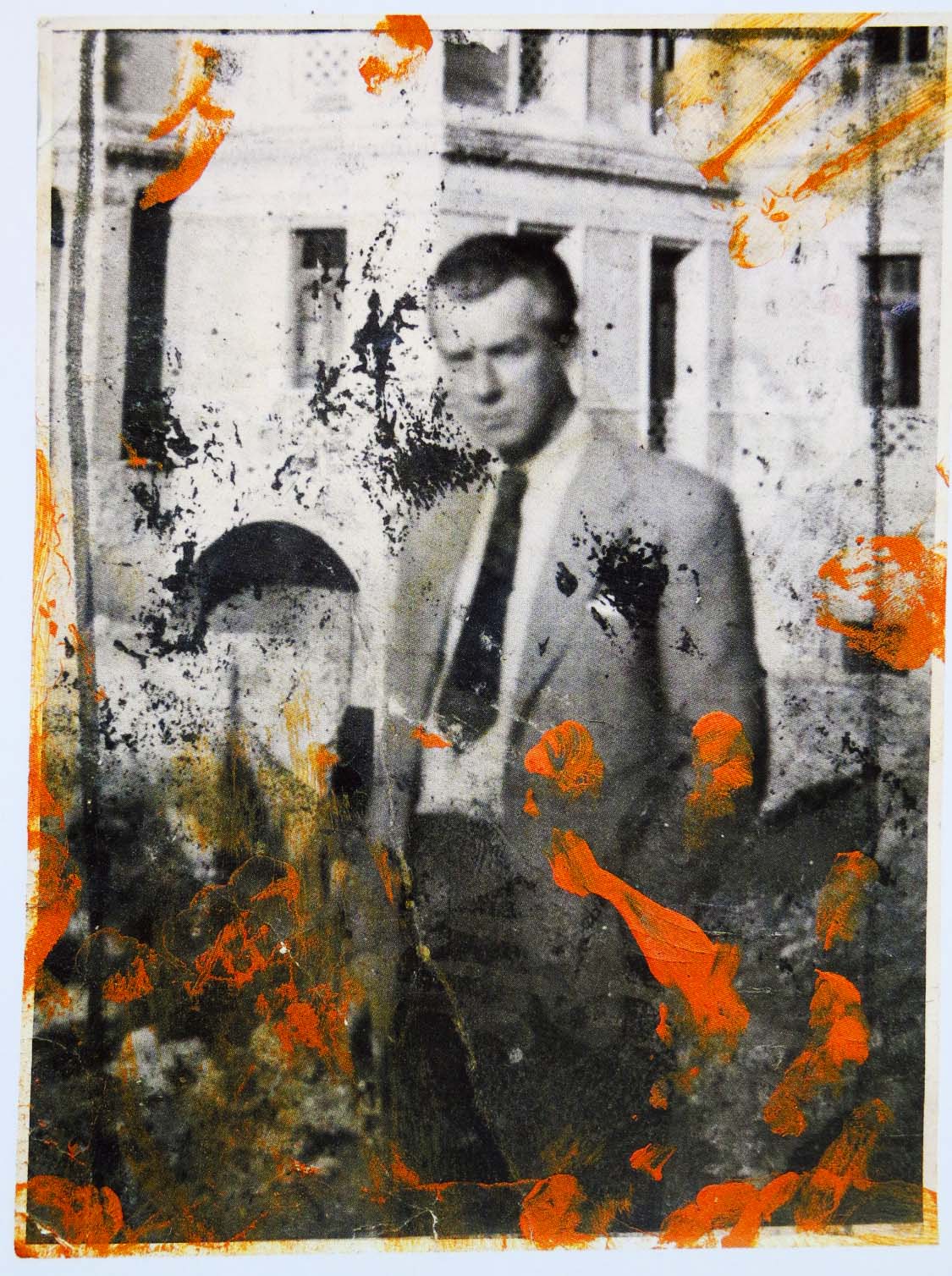

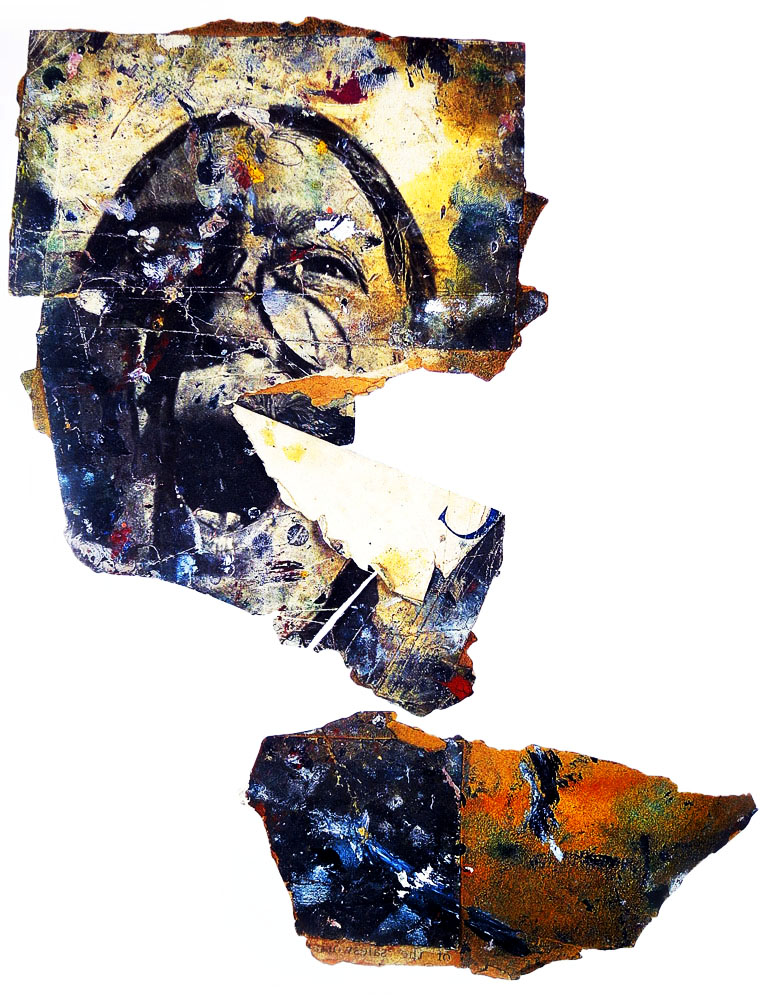

Chaos Breeds Images

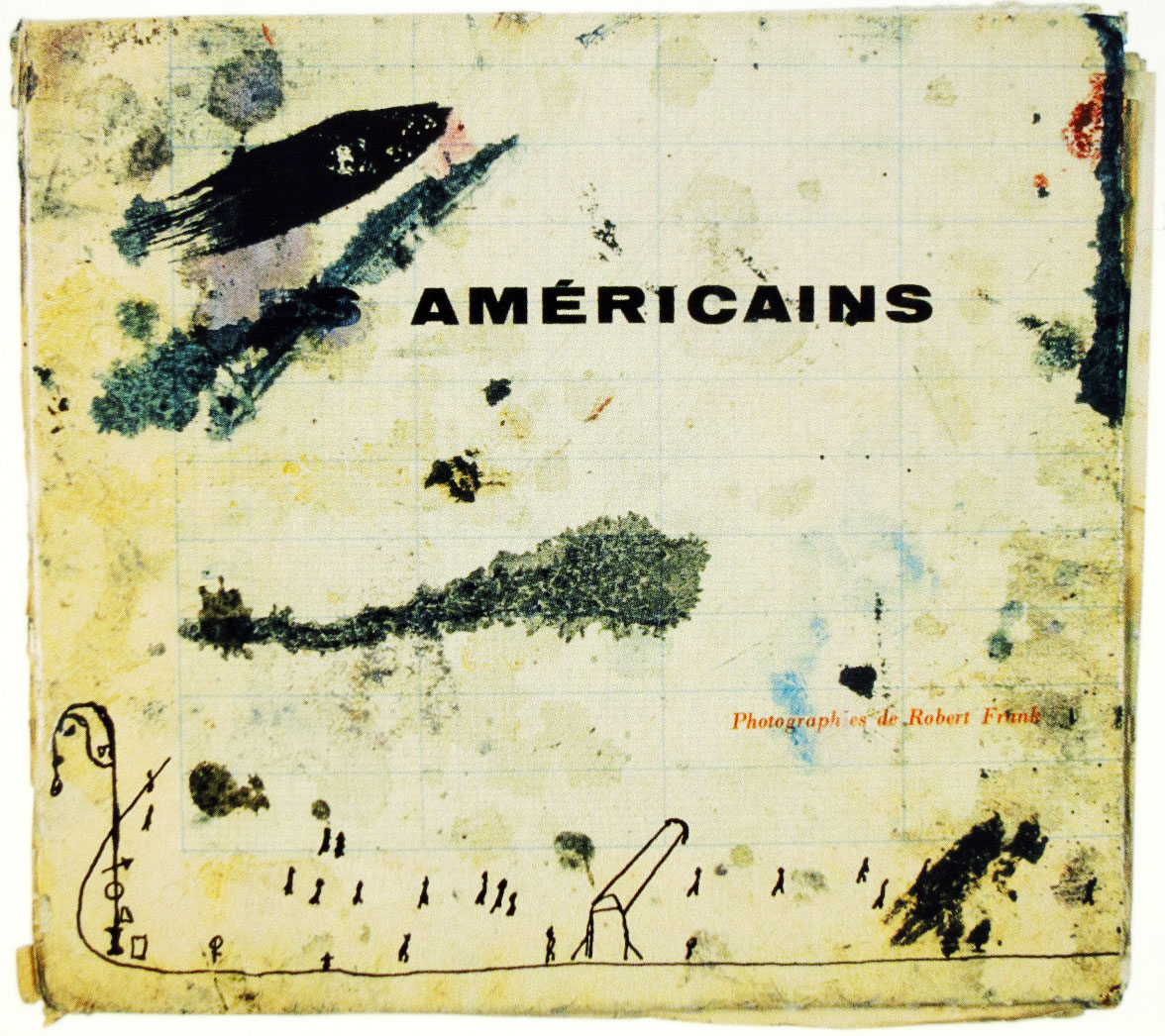

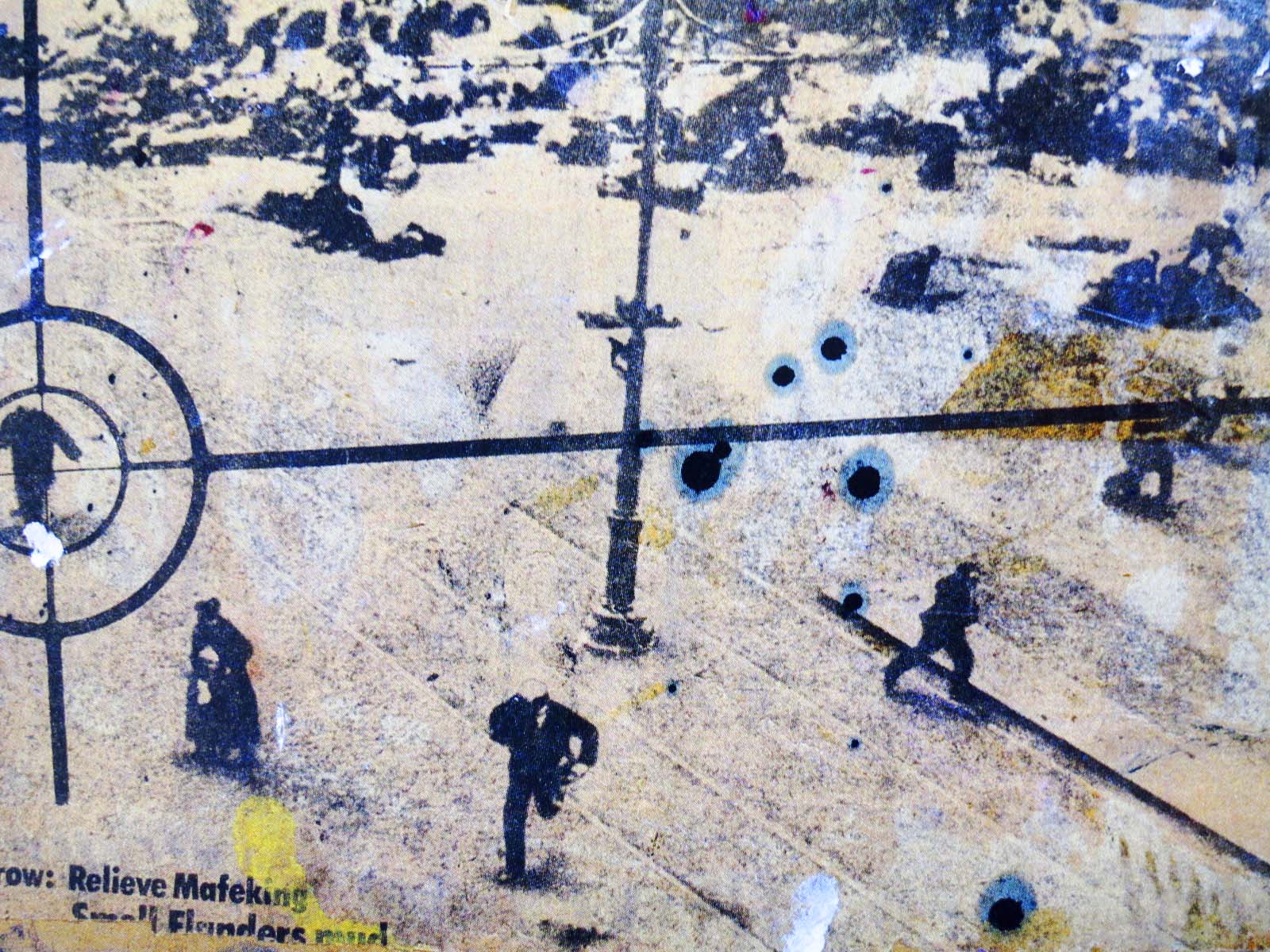

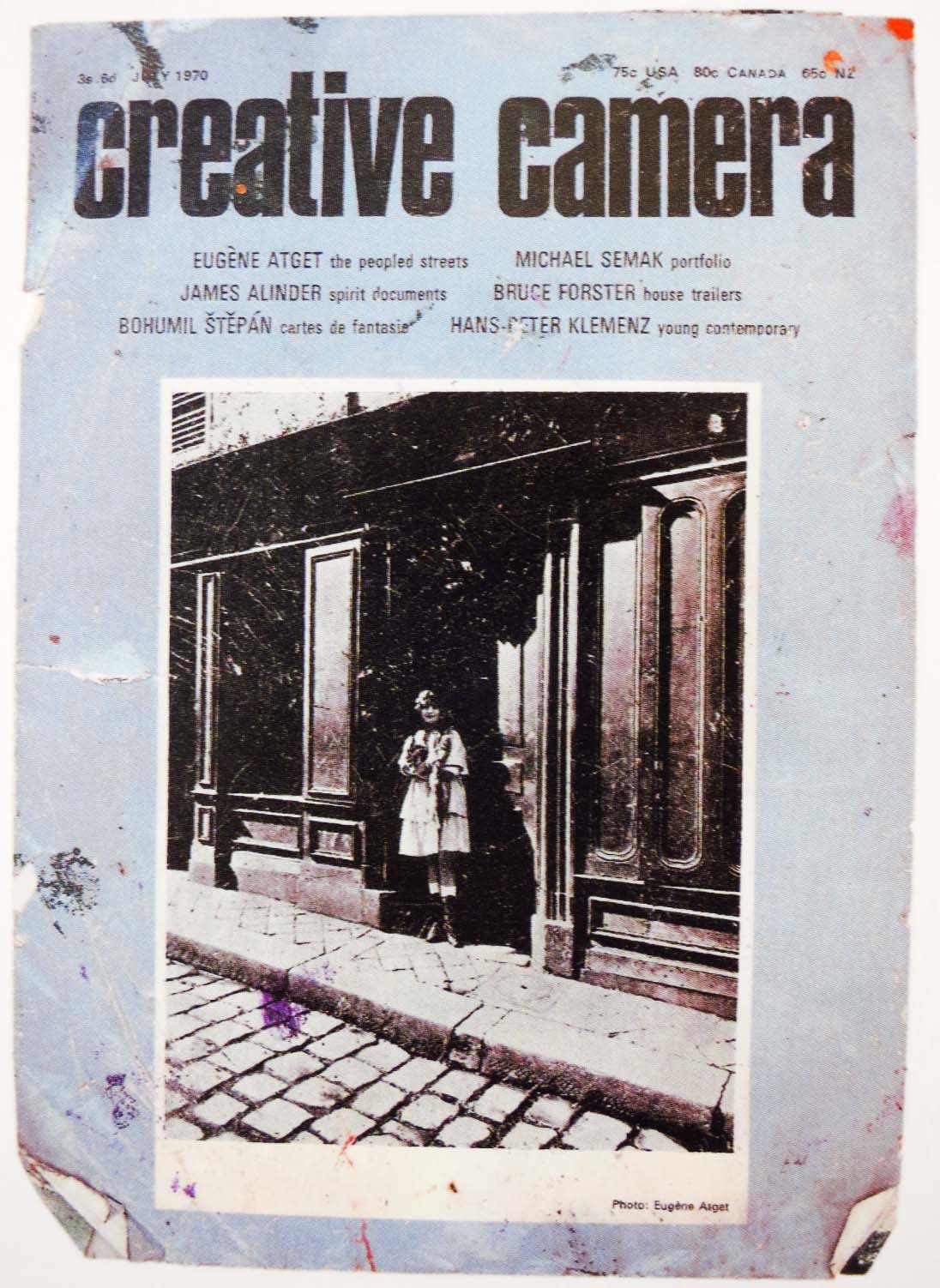

Oct 01, 2015 - John Maclean

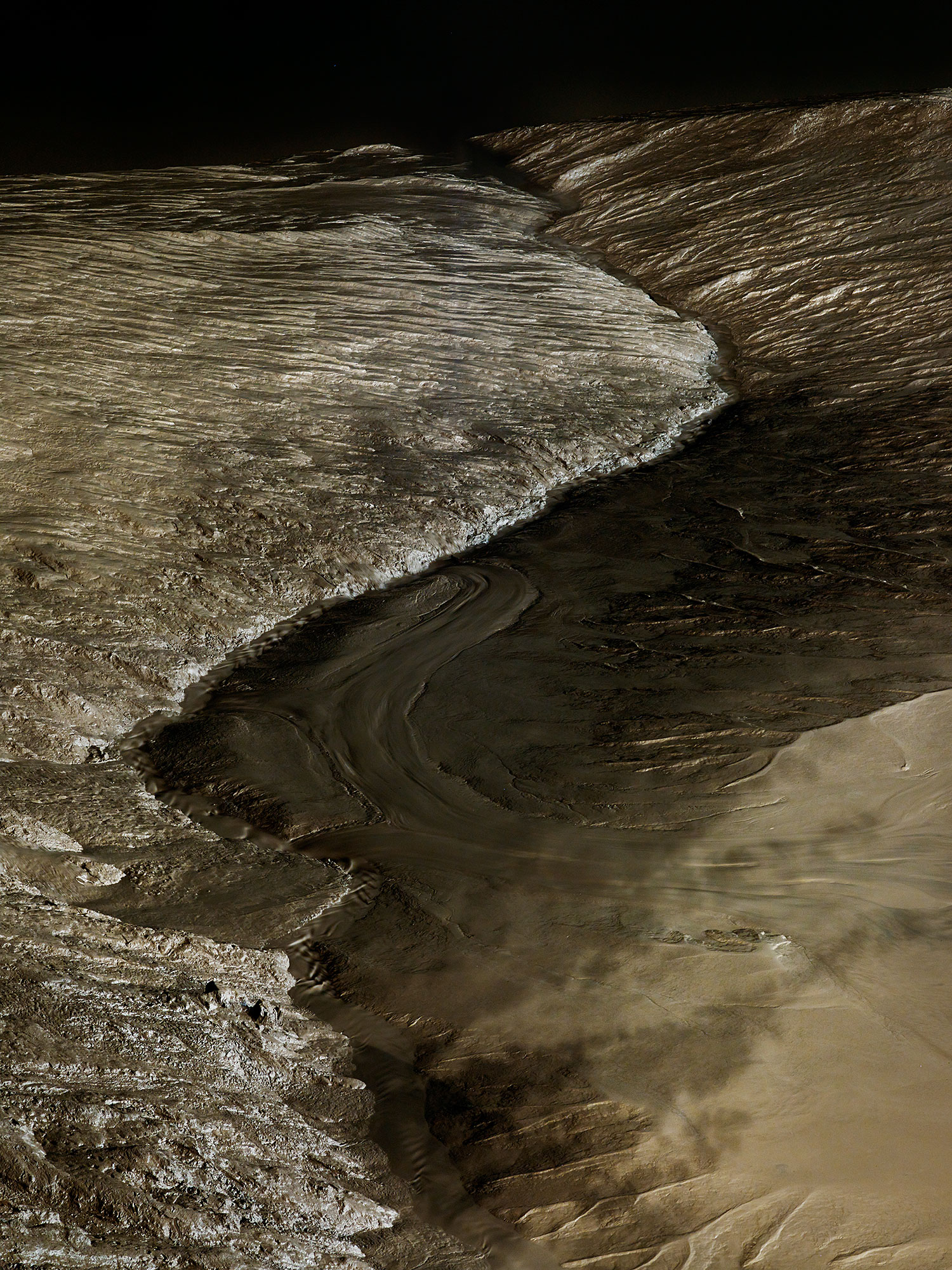

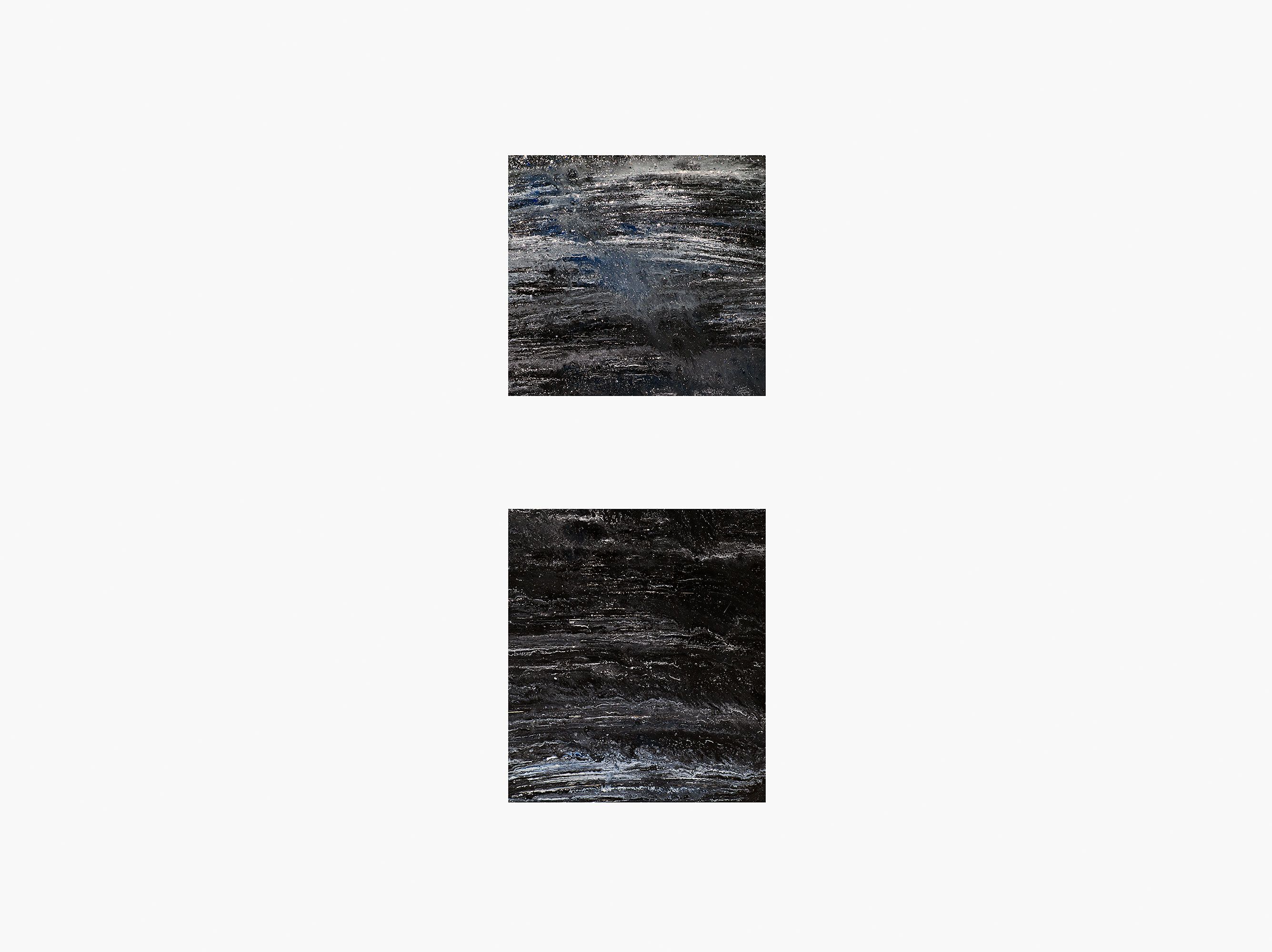

The images above are photographs of printed matter found on the floor of Francis Bacon's studio. They include a first edition copy of Robert Frank's The Americans. Below is a description of his studio by Dr. Margarita Cappock: Francis Bacon lived and worked in 7 Reece Mews, South Kensington from 1961 until his death in 1992. The Reece Mews studio was of immense significance for the artist and some of his finest paintings were realised in this small room. Photographs of the studio taken in 1964 show that layers of material had already begun to accumulate. The studio was to become Bacon’s complete visual world. Of his cluttered studio, Bacon said “I feel at home here in this chaos because chaos suggests images to me.” He rarely painted from life and the heaps of torn photographs, fragments of illustrations, books, catalogues, magazines and newspapers provided nearly all of his visual sources. Commenting on the wealth of photographic material in his studio, Bacon said that he looked at photographs for inspiration in the way that one looks up meanings in a dictionary. Photographs by John Deakin, Cecil Beaton, Peter Beard, Henri Cartier Bresson, Peter Stark and many others provide a fascinating insight into both the bohemian milieu in which Bacon operated and the artist’s method of manipulating his source material. On the studio floor, reproductions of fine art paintings jostled with illustrations of crime scenes, skin diseases, film stars, athletes and other imagery which clearly appealed to Bacon’s artistic imagination. Books and magazines on subjects including art, sport, crime, history, photography, cinema, bullfighting, wildlife and the supernatural were found in precarious piles on the studio floor and highlight the eclectic nature of Bacon’s influences. Some of the most significant studio items include seventy works on paper and one hundred slashed canvases. The vast array of artist’s materials, household paint pots, used and unused paint tubes, paint brushes, cut off ends of corduroy trousers and cashmere sweaters record the diversity of Bacon’s techniques. Other items found in the studio include the artist’s correspondence, a collection of vinyl records and some furniture. Bacon: Chance enables me to make images that my intellect could never make. Bacon: I’m just trying to make images as accurately off my nervous system as I can. I don’t even know what half of them mean. Bacon: I have no idea what any artist is trying to say – except the more banal artists. A story about Francis Bacon told by poet and writer Anthony Cronin: "Perhaps the most revealing story I personally remember Bacon telling about his early childhood in Ireland concerned a maid or a nanny - I had the impression of a sort of Irish mother's help - who was left in charge of him for long periods when his parents were absent from the house. She had a soldier boyfriend who came visiting at these times; and of course, the couple wanted to be alone. But Francis was a jealous and endlessly demanding little boy who would constantly interrupt their lovemaking on one pretext or another. As a result, she took to locking him in a cupboard at the top of the stairs when her boyfriend arrived. Confined in the darkness of this cupboard Francis would scream - perhaps for several hours at a time - but since he was out of earshot of the happy courting couple, completely in vain." "That cupboard," Bacon apparently said years later, "was the making of me." Bacon: I am very influenced by places — by the atmosphere of a room… I just knew from the moment I came here (Reece Mews Studio, Kensington, London) that I would be able to work here.