Artist Blog

Every week an artist whose single image was published by Der Greif is given a platform in which to blog about contemporary photography.

The Age Old Question

Mar 19, 2017 - Stacy Mehrfar

What makes a good portrait? That’s a question I throw around on a daily basis. It’s safe to say that the answer changes just as often.

While researching for The Moon Belongs to Everyone, I played close attention to the way different artists have tackled the photographic portrait. Here I will go into detail about three artists who’s work I admire and who’s photographs have long influenced my thinking, and my practice.

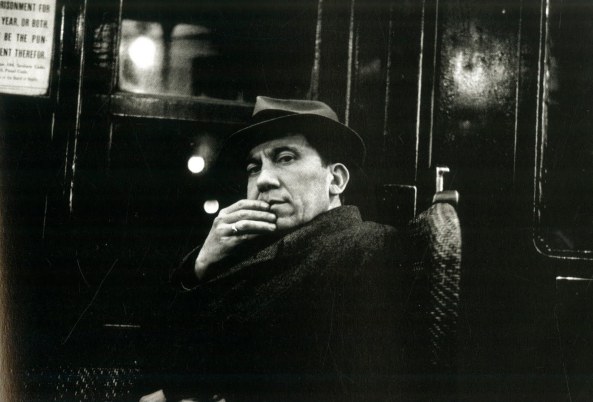

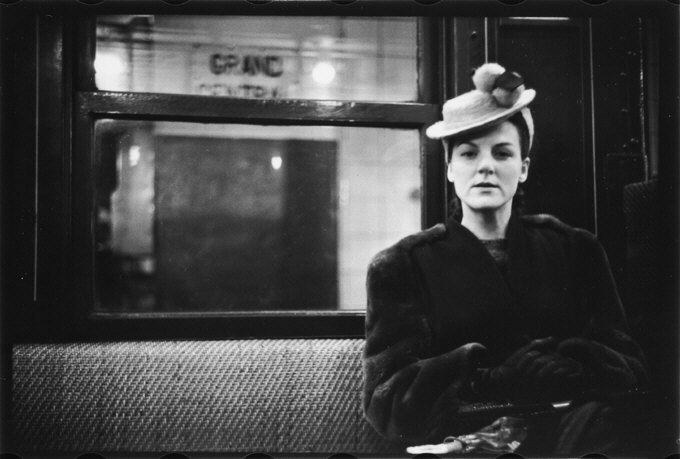

Walker Evans, Many Are Called: Between 1936 and 1941, Walker Evans, one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, photographed passengers in New York City subway cars in what came to be the book entitled, Many Are Called. These photographs were essentially shot ‘from the hip’; Evans hid a camera beneath his coat and a shutter release down his coat sleeve so he could be as surreptitious as possible. The images captured the ordinarily unseen – essentially presenting photography’s ability to depict the in-between, the unguarded, expressions of a human subject. Of the images in Many Are Called, Evans writes, “[These images are] my idea of what a portrait ought to be: anonymous and documentary and a straightforward picture of mankind.” (1)

We are given very little information about the subjects of the photographs. However, Evans’ camera seemingly crosses the boundary from the curious to the familiar, where the photographed subjects ostensibly transform into representations, or allegories, for human emotion. The individual photographs can be seen as an observation of a contemplative moment of a given subject. However, viewed together, the series of images forges a story, a metaphor, a picturing of a group of people in a specific place at a specific time. With each turn of the page, we become aware that what we are observing is a collective identity of New York City in a specific moment in time.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Heads: American photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia also intended to make an artwork that offered an intimate look at New York City’s collective identity. This work, entitled Heads, was exhibited in September 2001 (it opened one week before the tragic events of 9/11 in New York City), and was concurrently published in a book. The significance of diCorcia’s Heads is the exploration of what the camera reveals through ‘the gaze’ and how that gaze can evoke meaning through portraiture. With the camera positioned at a distance of 20 feet, and a flash and a trigger set up on the scaffolding of the streets of New York’s Times Square, the subjects of Heads were photographed unawares. The images in the series are all photographic portraits — close-up, intimate, captured moments of anonymous subjects. The use of a telephoto lens and flash bring the subject(s) out from the background, effectively framing images that offer no specificity of location, thereby focusing the viewer’s gaze onto the subjects’ gaze and pose.

diCorcia’s portraits are reminiscent of techniques used by seventeenth-century artists, where the communication of a private, inward state of a subject is suggested through the manipulation of gesture and form, light and shade. With the employment of strongly lit, bold archetypical faces measured against dark, indistinct backgrounds, diCorcia draws on these conventions. The engagement of such effects, or photographic tropes, directs the viewer’s gaze, leaving she or he with the sensation of being caught looking deep within the subject’s inner thoughts.

Rineke Dijkstra, Beach Portraits: Beach Portraits (1992–2002), a series of full-length color photographs of teenagers and children photographed at the ocean’s edge in the United States, Poland, Britain, Ukraine, Gabon, and Croatia, is just one example of Rineke Dijkstra’s photographic portrait work. In this series, as in the majority of her photographs, Dijkstra draws on a standardised, formal aesthetic to directly address individual identity. Without instructing her subjects on how to stand, or sit, or where to look, Dijkstra’s placement of the camera directly in front of her subject(s) is deliberate. Through a direct lens perspective, Dijkstra allows her sitters the power of the gaze: each subject is given the opportunity to gaze back at the viewer and acknowledge that their image is there to be examined. Her photographic portraits are honest, bold, and dynamic. Rineke Dijkstra’s photographs summon the viewer’s attention — forcing us to look, to examine, to decipher, an individual’s identity.

1. Jeff L. Rosenheim, afterword to Walker Evans, Many Are Called, with an introduction by James Agee, foreword by Luc Sante, and afterword by Jeff L. Rosenheim (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in Association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), 198.