Natalie Krick

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

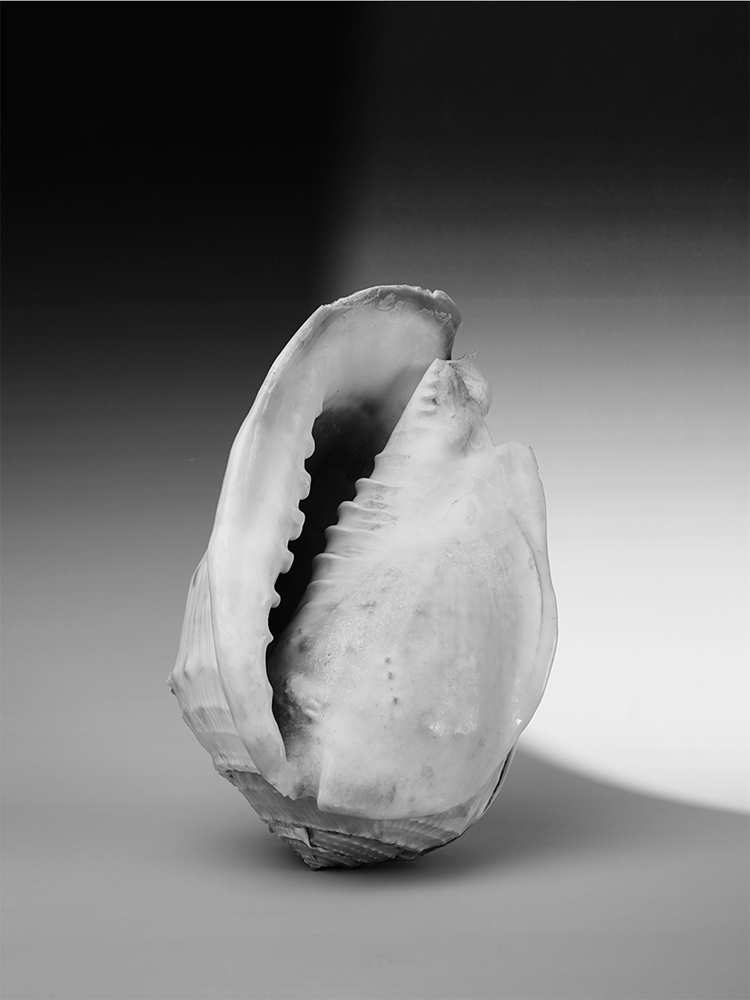

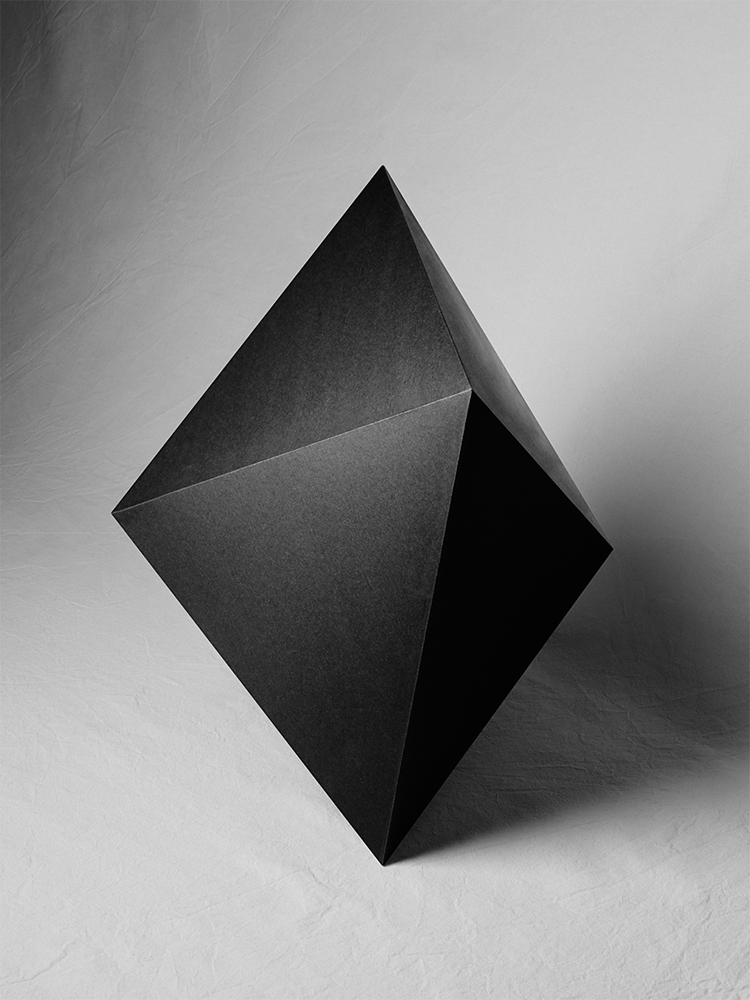

Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup - Blank

Jun 02, 2017

Bearing no marks; not written upon; empty; fruitless; abortive; entirely without interest; nonplussed; unrelieved; expressionnless; sheer absolute; with spaces left for details; without ornament or break; unrelieved; not filled in; empty; void; exhibiting no interest or expression; lacking understanding; confused; absolute; complete; devoid of ideas or inspiration; an emptiness; blank space; characterized by incomprehension or mental confusion; unfinished; unrecorded or erased; fading away; colorless; appearing or causing to appear dazed or confounded; lacking incident or result; temporarily having no knowledge or understanding; showing no emotion; without memory; lost; which is irrelevant; worthless; meaningless; who has no psychological depth; break in continuity; where something is missing; lacking reality or value; state corresponding to the total absence of any real particle; nothingness; vacuous; feeling absence;

«With the advent of photography, the relationship between images, the real and the body of the artist have undergone tremendous changes. Photography stands at the crossroads of «two series of secular knowledge and dispositive: on one side, the camera obscura, optics; on the other side, the sensitivity of certain substances to light».1 It is this encounter between optics and chemistry that has resulted in the ability to capture luminous phenomena. For the first time, a machine replaces the human hand and vision as a device to visualize (represent) the world. There is an urge to see this new device as a possibility to compensate for human deficiency. A sudden appeal emerges for objectivity, global vision, and loss of hierarchical structure -in brutal contrast to older modes of representation. A new connection between the things of the world and images is sealed: whereas «manual images come from the artist himself, away from the real, photographic images, which are luminous imprints, associate the real and the image, at a distance from the operator. The ancient unity man-image is being replaced by a new unity real image».2 In that sense photographic images are not a «representation» (a description, a symbol, a spectacle) of the world but its «capture» (a seizure): they do not depict the real but show the visible, they display – representation, icon, imitation opposed to imprint, index, recording.» «It is interesting to see here how deeply the advent of the digital has further undermined long-term beliefs regarding photography. It has brought a new light onto elements that were part of the medium from its birth, but rarely as prevalent as they are today: that photography is not inherently linked to truth and reality. Photographic causality, its analogue direct link to its referent, which has led to an almost unquestionable claim for veracity, has been torn down. Digital images are no longer dependent on the «real world» for their existence. In the words of Martin Lister: «such a «photograph» may be based on knowledge of, but not caused by, the action of light reflected by a particular object. But what it does refer to is other photographs».3 For that reason – the resemblance with traditional photographs they wish to attain, and often do – they «carry the [same] authority and information».3 » «I understand photography as a means of perception. Images, «established – in the realm of the virtual – by the artist but dependent on the beholder for their realization, and their property is to make the beholder aware […] of the active, subjective nature of seeing».4 I am interested in understanding how photography can be used as a way to alter our perception and to express incidents invisible to the bare human eye. How can photography suggest a continuous flow of time and space, and a constantly changing or manipulated reality?» These are three short excerpts from an essay I wrote on the nature of photography, perception and reality (Perception, Lies and Reality, selfpublished, Lausanne, 2012). They embody what is at the center of my photographic practice and approach to the medium. With the project «Blank», I am attempting a visual exercise at representing these notions. The images carry the authoritative quality of photography, its narrative properties and an attempt at capturing the abstract and conceptual qualities of light and perception. Bringing together heterogeneous techniques and modes of representation, mixing «straight photographs» with highly manipulated images thus blurring the fine line between fact and fiction they are an experiment on bringing forward the unfathomable and deceiving qualities of the medium, while retaining a narrative quality open to personal interpretation and a search for a certain truth: «there is not the truth of one reality by which one might then even deduce that another, different perception is not true. The notion of reality itself can only be used in the plural. That is where the reality of the images lies; only if one believes in the truth of one reality one can talk of «lies». Thus true lies is the befitting expression for a contemporary perception of reality that cannot be limited to one single perspective any longer».5

1 – p.35 ROUILLÉ, André. La Photographie. Paris: Editions Gallimard, folio essais, 2005

2 – p.36 ROUILLÉ, André. La Photographie. Paris: Editions Gallimard, folio essais, 2005

3 – WELLS, Liz. Photography, a critical introduction. New York: Routledge, 1997 – p.260 «Photography in the ageof electronic Imaging».Martin Lister

4 – p.18 GAMBONI, Dario. Potential Images: Ambiguity and Indeterminacy in Modern Art. London: Reaktion Books, April 4, 2004

5 – p.13 SPIELER, Reinhard, Nolte Gertrud. True lies: Lügen und andere Wahrheiten in der zeitgenössischen Fotografie = lies and other truths in contemporary photography. Katalog zur Ausstellung Museum Franz Gertsch, Burgdorf, 18.01.-28.03.2004. Bern: Atelier Verlag, 2004

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Guest-Room Bruno Ceschel«

Perception, Lies and Reality: Conclusion

Jun 09, 2017 - Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup

[…] Through all the works presented here, something becomes very clear: the idea that photography accounts for an all encompassing and neutral vision, a mirror of reality and a medium that never lies – free from human subjectivity – is no longer at the center of the medium. Rather, photographers are utilizing the essential components of photography (optics and light sensitive materials, digital or analogue) to investigate new ways of creating images. More often than not, these are constructions of the mind; images well thought out, researched and built to represent as faithfully as possible the idea in the photographer’s mind, and the message or sensation he aims to convey. Photography has here merged with the other visual arts that were at all times seen as inherently infused with the artist’s hand. The epoch when photography was seen as a device enabling pure mechanical reproduction, one that was able to capture the essence of the things and people it depicted by means of a direct and physical trace between the object or person and the resulting image seems past. We must also not forget that images generating a controversy regarding their veracity (such as Robert Capa’s «Death of a Loyalist Soldier, 1936») or clearly manipulated (as for example the photograph by I.P. Goldstein of Lenine addressing soldiers on may 5th 1920, where the figures of Trotsky and Lev Kamenev have been removed in an attempt to rewrite history) have appeared throughout the history of photography; years before the development of digital photography and more recent scandals in the news. However, we have been in the state of mind of believing photographic images for such a long time, that it is hard to start distrusting these images constantly. Our reflex, when first seeing a photograph, remains to believe what we see. It is this that enables photographers to play with our understanding of images: it is a play with our beliefs, which are still deeply anchored in us, and an echo to the thousands of images we have stored in our heads. I would like to conclude with a quote from Reinhard Spieler, which I believe gives a good ending and conclusion to this research: «there is not the truth of one reality by which one might then even deduce that another, different perception is not true. The notion of reality itself can only be used in the plural. That is where the reality of the images lies; only if one believes in the truth of one reality one can talk of «lies»L. Thus true lies is the befitting expression for a contemporary perception of reality that cannot be limited to one single perspective any longer».35

[…]

L – Lie: to mislead, untrue | to play wit the spectator | intentionally false

35 – p.13 SPIELER, Reinhard, Nolte Gertrud. True lies: Lügen und andere Wahrheiten in der zeitgenössischen Fotografie = lies and other truths in contemporary photography. Katalog zur Ausstellung Museum Franz Gertsch, Burgdorf, 18.01.-28.03.2004. Bern: Atelier Verlag, 2004

Perception, Lies and Reality: Illusion

Jun 08, 2017 - Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup

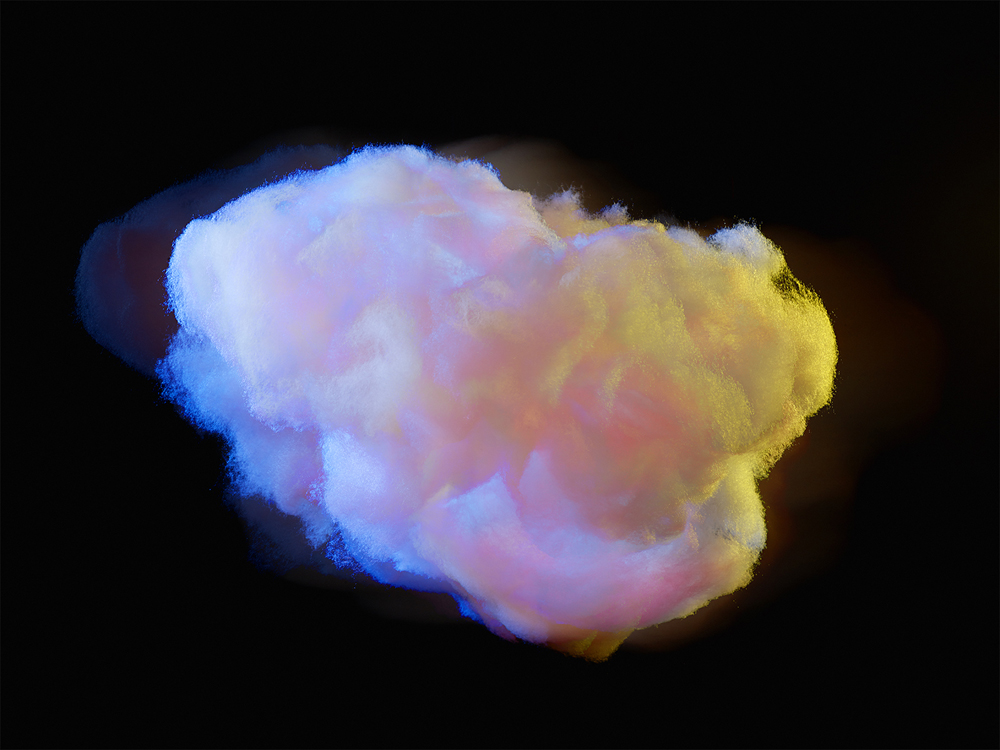

Illusion

[…] These images reinforce the effect of «constructed» images of the previous category as they add illusion. Using both elements, an aspect of construction and of optical illusion, they accentuate the illusory, elusive and ephemeral qualities of photography. They give materiality to a vision that can only be seen either through the lens, from a particular angle – generating new forms for the sole purpose of being photographed – or with the aide of digital technology. They do not pretend to depict anything real, rather they play with the abstract, the mental and the absurd.

The work of Lukas Blalock, in a quite opposed style, deals with similar notions of constructed and illusionistic images – which involve both a physical building and an important part of postproduction. Blalock’s photographs seem at first to stand in total contrast to the series I mentioned previously, with his rough digital work, his intentional disclosure of the mechanics of the construction. His images are no perfect illusions, rather they are a comment on the construction itself: they hint at, and deliberately show, the manipulations behind the scene. He uses all the tools at hand to create perfect images, all the tricks used in advertisement, in a deliberately coarse manner to expose them. The end product resembles collages, unfinished paintings or other seemingly rapidly made images using Adobe Photoshop in the «wrong» way: applying masking techniques The work of Lukas Blalock, in a quite opposed style, deals with similar notions of constructed and illusionistic images – which involve both a physical building and an important part of postproduction. Blalock’s photographs seem at first to stand in total contrast to the series I mentioned previously, with his rough digital work, his intentional disclosure of the mechanics of the construction. His images are no perfect illusions, rather they are a comment on the construction itself: they hint at, and deliberately show, the manipulations behind the scene. He uses all the tools at hand to create perfect images, all the tricks used in advertisement, in a deliberately coarse manner to expose them. The end product resembles collages, unfinished paintings or other seemingly rapidly made images using Adobe Photoshop in the «wrong» way: applying masking techniques and other tools, he stops half- way to leave the evidence of the construction. He explores ways in which falseness and the disclosure of the mechanics can point to specific aspects of the photographed, and to photography’s inherent ability to confuse and alter reality, as we know it. They are a very interesting comment on the state of contemporary photography and the actuality that images are becoming ever more counterfeit. They disclose better than ever the fact that all images are manipulated, constructed and illusions. As Blalock himself explains, it is less about the mechanics of the camera than the viewer’s direct interaction with the pictures: «I am interested in the photograph’s power to direct and focus attention. […]. For me the digital interventions are less in terms of the image than they are about bringing out specific qualities in the objects, places, or people photographed. I want pictures to feel provisional, and to in some way make the viewer aware of my choices as well as the set of possible choices inherent in the making of the image. I […] believe that by making people aware of the mechanics of a situation you more fully engage them in the possibility of its outcomes».34 The illusion is here more in the way he engages the spectator to open his eyes to new visions and to the many possibilities at hand when making an image. The falseness is made evident to reinforce the elusive qualities of photographs.

It is surprising to see how two diametrically opposed approaches bring a similar effect on the spectator: wonder, disbelief, and a forced mental reading.

[…]

34 – http://hafny.org/exhibitions/soloshow/lucas-blalock-sam-falls/interview/

Perception, Lies and Reality: Constructed reality

Jun 07, 2017 - Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup

Constructed reality

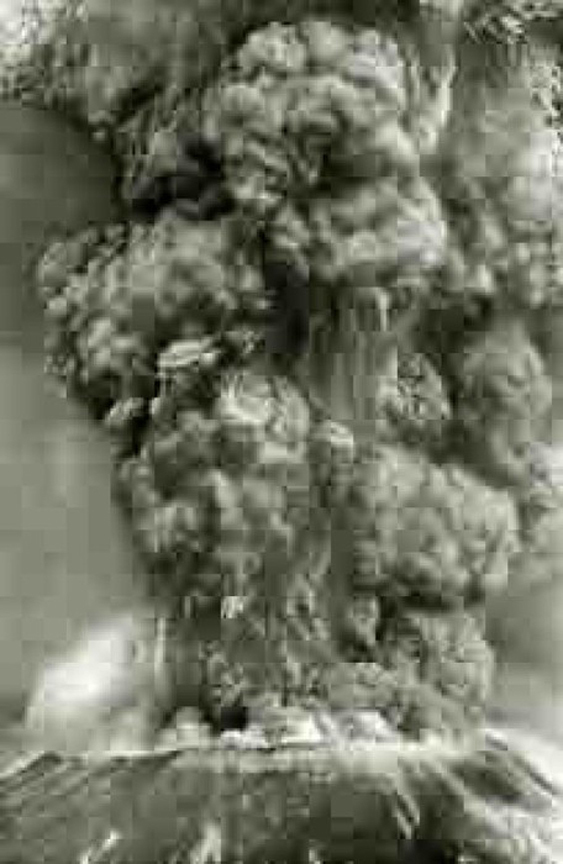

[…] This category is precisely concerned with constructed reality: photographs of small-scale worlds made to lure the viewer into confusion. They are photographs, which appear, at first sight, to be «normal» straightforward depictions. Only if we look very closely, do we realize that they are «fake». They directly point to a coming together of a collective memory and ideas about specific events, places or periods in time and history with more personal recollections. They give form, almost in an attempt to bring them to life, to mental ideas resulting from a converging of various sources of information (drawings, writings, the media, scientific analysis, etc.). There is no truth in these images, except that they are actual reproductions of (small) constructions, which were already a reinterpretation of «reality». They are a beautiful but insidious play with our minds.

Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs of dioramas are a good example. The absence of perspective and defined background, the precision of details and the smooth lighting with its delicate shading from black to white give us the impression to be staring at a wide-open space – a space, which recalls untouched land and wildlife. We barely notice that, in some of the images, the figures are replicas of ancient men or dinosaurs. In a way, they bring to life our fantasized idea of the past; using a «true» constructed reality, they play with our imagined conception of certain places and times. We are faced with a representation of mental ideas: ideas put into our heads by other depictions such as writings, paintings and illustrations. Thus when we see a seemingly «real» photograph of these, in an unforeseen coming together of our interior world with the one surrounding us, we loose sense of what is true or false.

Thomas Demand pushes this «construction» even further. He himself builds small-scale architectures, which are meant to last just long enough to be photographed and «attain perfection at the precise moment when he releases the shutter».32 He pushes the accuracy, as far as to construct the models with, in mind, the point of view from which he will photograph them. His models are so well done, that it is only in the small imperfections that we discover over time, that we start to see their «fake» aspect. He plays very directly with our perception, and the notion of multiple interpretive levels: he represents places, buildings, rooms, which are based on his personal experience, while they are reminiscent of a particular moment in time and history. He compels the viewer to dive into his own memory and look for significations, relying heavily on the media and their shaping of a collective memory. Demand plays with the mundane, the banal, the ordinary and how it can encompass memories, dreams and narratives: «a continuous shifting between reality and fictionK is fundamental to Thomas Demand’s works which are ambiguous screens placed at the boundary between abstraction and detail, between formal materiality and two-dimensional illusion. His photographs are expansive fields on whose surface media images, personal memories and collective history intersect».33 The images are constructed edge to edge, with no place for escape. The viewer is literally drawn in and forced to reflect: faced with a reproduction of an «image» of his own real life experience and memory, he starts to ponder on how much these recollections were also manipulated. The «fake» of the models evokes a manipulation of the real world.

[…]

K – Fiction: narrative, telling of a story, message | to represent, to idealize, to create | personal view/vision | fake but not necessary untrue | something that is invented, made up and constructed

32 – Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea. Thomas Demand. Gineva-Milano: Skira, 2002 – p.10 «Thomas Demand: The Image and Its Double». Marcella Beccaria

33 – Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea. Thomas Demand. Gineva-Milano: Skira, 2002 – p7. «Thomas Demand: The Image and Its Double». Marcella Beccaria

Perception, Lies and Reality: Scale

Jun 06, 2017 - Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup

Scale

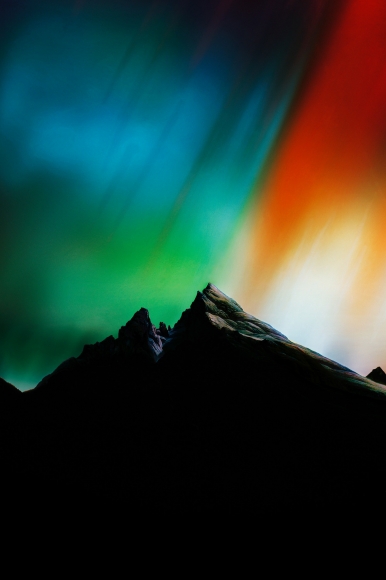

[…] In this category of images the notion of painting and scale play a major part. The photographers presented here create images, which play with our perception of what is clear and intelligible and depend on an active reading from the spectator. These photographs many times ask for a somewhat physical reading as we are forced to move back and forth (in space) in order to grasp the various layers of reading. Often forcing us to dive into our personal recollections, whilst relying heavily on a collective memory generated by the media, they touch upon the degree to which our understanding of reality can be manipulated through images. There are here no clear outlines, everything gets blurred and with it the impossibility to point to a sole and unique version of the truth comes to light. The vision of photography as a mirror of reality is shattered.

Jules Spinatsch’s image «discontinuous panorama A240635, 2003» encompasses the concepts of time and narration present in Hilliard’s photographs, while inviting for a new reading which involves a notion of scale. The spectator can either glance at the «photograph» in its entirety, or zoom in. When the image is looked at closely, we realize that each of the pixel-like squares, which form the whole image, is actually a photograph on its own. Suddenly, new interactions emerge, stories are created and we are forced to move back and forth while looking at it. The macro and micro converge in a new dimension.

A similar phenomenon is present in Thomas Ruff’s series «jpeg». In this series Ruff uses digital images that he enlarges way beyond their «size». He enlarges them to a point where the pixels become truly apparent, where the images lose their sharpness and capacity to precisely describe the object or landscape photographed. The viewer is forced to go back and forth between a global look and a zooming into details. The confusion remains: from up close the pixels become like blown up brushstrokes with no apparent relation to one another; from further away the pixelated image prevents us from fully grasping what is pictured. We are forced to recall images present in our memory, to make sense as to what it evokes. In Susan Sontag’s words: «Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy».27 Furthermore, in treating idyllic images (landscapes) in the same way as dramatic subjects (bombings) «it is impossible not to draw parallels between this experience and the daily bombardment of visual stimuli to which we are subjected, without much discernment, as to the veracity of what we are seeing. In other words, Ruff’s process emphasizes how easily the visual messages that enable us to relate to reality can be manipulated, and how fleeting their grasp of truth is».28 This brings us even deeper into the notion of perception, as we are here faced with images that play not just with the notion of point of view, but with that of a manipulated and constructed reality: «Ruff’s entire body of work is informed both by a desire to experiment with different modes of expression and by an acute awareness of the realistic effects that the camera is able to produce».29

Florian Maier-Aichen, falls more into the relationship to painting of this category, as he creates composite images in direct reference to paintings. Using a great variety of techniques – drawing, painting, photography (analogue and digital) and animation stills – he reshapes his photographs into creations straight from his mind. With these fantastic illusions, he overrides photographic truth and plays not only with the real, but also with the medium: «subverting the expected documentary quality of photography, Florian Maier-Aichen approaches his medium as a form of painterly illusion. Adopting his process as a means to «draw with light», his photos blur fact and fiction».30 Maier-Aichen plays with constructionJ an all levels, to «produce seemingly straightforward photographic landscape subjects while other images that engage the most conventional photographic techniques may themselves be subjects of pure fabrication».31 The spectator is once again left wondering, despite the fact that the images somewhat blatantly point to their untruth (being often too abstract, too idealized, or displaying otherworldly colors), where and when the disbelief should begin. We are here seeing a sort of ideal process of image making, which includes at once the most advanced techniques (digital photography, virtual imaging, etc.) as well as ancient ones; a process that allows new visual creations and perceptions.[…]

27 – p.23 SONTAG, Susan. On photography. New York: Picador USA, 1st édition, August 25, 2001

28 – Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea. Thomas Ruff. Milano: Skira Editores S.p.a, 2009 – p.42 Giorgio Verzotti

29 – Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea. Thomas Ruff. Milano: Skira Editores S.p.a, 2009 – p.34 Giorgio Verzotti

J – Construction: building, shaping, creating something new | the creation of an abstract entity | physical, mental and virtual | intervention (artist/human)

30 – http://www.saatchi-gallery.co.uk/artists/florian_maier_aichen.htm

31 – http://www.artrabbit.com/uk/events/event&event=14161

Perception, Lies and Reality: Fragmented temporality

Jun 05, 2017 - Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup

Fragmented temporality

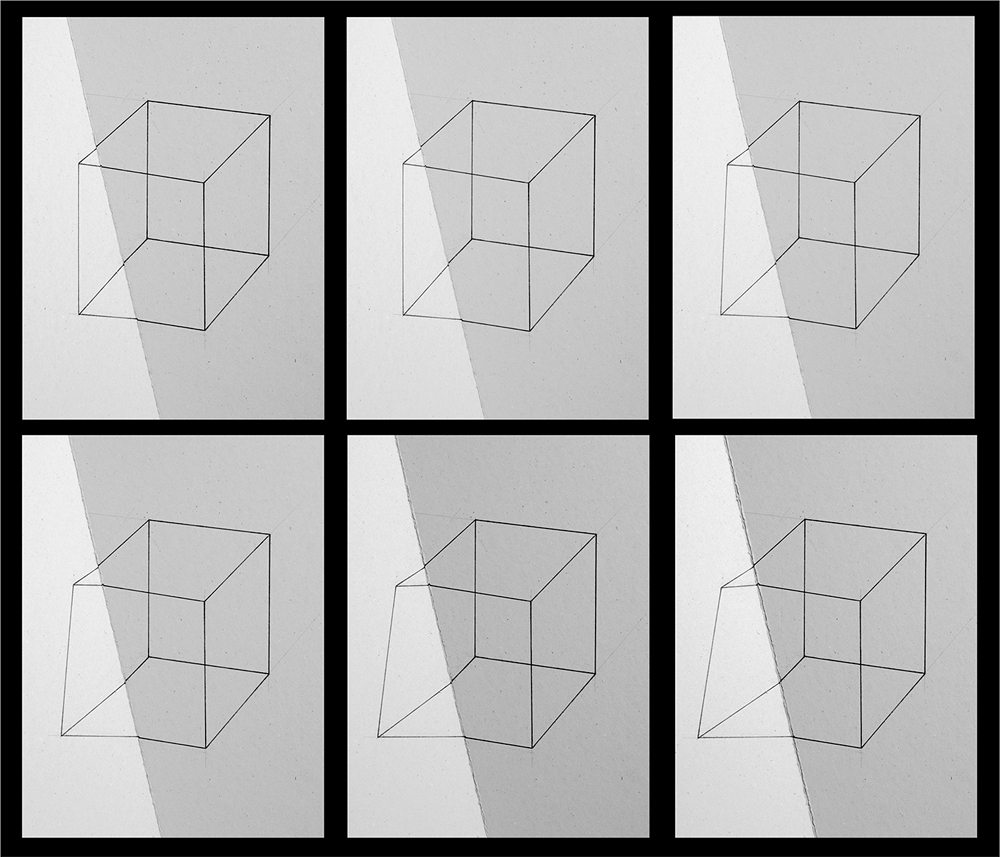

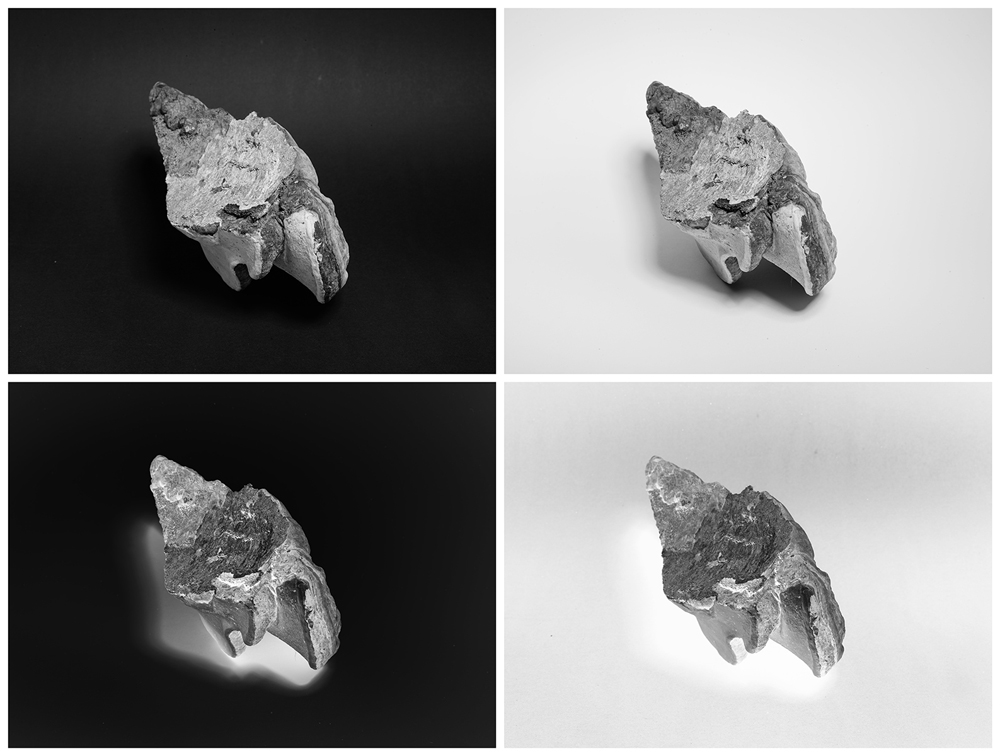

[…]This category still has at its core the idea of temporality, but in a more fragmented way. We are no longer faced with a continuum, an image that encompasses a span of time. Rather, we are seeing here, in Maurice Merleau-Ponti’s words, «a world in which no two objects are seen simultaneously, a world in which regions of space are separated by the time it takes to move our gaze from one to the other, a world in which being is not given but rather emerges over time».22 Thus, this type of images engages the viewer in a more active reading, a reading in which he becomes a core element of the work. Again, it is disproving the so-called decisive moment and the idea that the world can be contained in one single frame. The conception of photography as a tool for objectivity is shattered here as well. We are forced to see how immeasurably small changes may affect the interpretation of an image and how everything depends on the point of view: everything depends on the man behind the viewfinder, the decision maker. Photography is not a mere mechanical reproduction, but one involving human intervention.

Walter Niedermayr’s photographs (fig. 29, 30) are fragmented, allowing for small shifts of point of view, which extend and transform the image «into an image-activity by the lively contribution it imposes on the viewer, who must shift his or her attention back and forth between the parts. The observer is thus in the midst of the image, and the isolated presence of the individual image is overcome and merged into something communal».23 These fragmented images, through the repetition of certain elements – the people walking through the landscape – and the slight changes in perspective at once allude to the impossibility of capturing the entirety of a place. Meanwhile, in their precision, attention to details and careful play with light and colors – or the lack of it: whiteness – they allude to photography as a medium. Despite the omnipresence of certain natural elements – the mountains – and the intrusion of human beings with an attitude obviously harmful to these original landscapes, Niedermayr’s images are not concerned with environmental issues. They touch upon the nature of photography and its relation to time. They embody an «eternal gaze looking down on a mythic but changing landscape and moments of frozen time, as if the visible is in the process of disappearing into whiteness, not fading away but condensing into a crystal clear image engraved on the retina».24

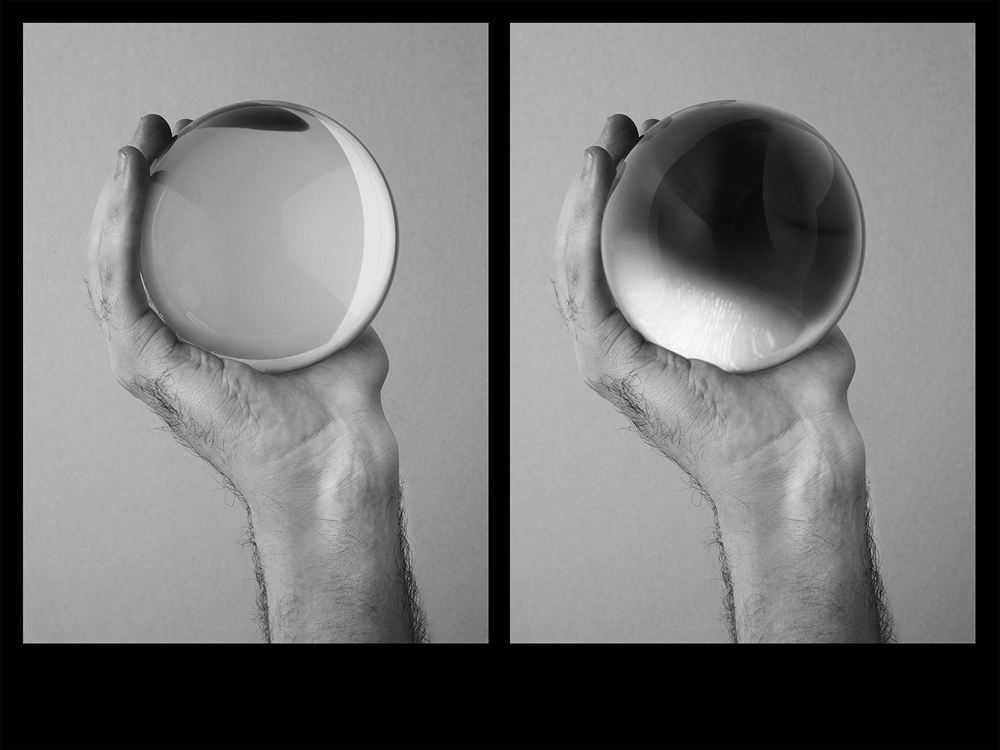

Roni Horn’s series «Becoming a landscape» (fig. 31) also uses the form of multiple images, this time however to show the minute alterations which take place within the interval of a fraction of a second. Unlike Niedermayr with his vast landscapes, her images leave no room to breathe and escape. She exposes the viewer head on to what seem at first sight to be two exactly similar photographs. Slowly, as we look at them, small differences emerge, and with it the interrogation: which is closer to reality? Is there but one reality? By creating an interaction between the images, and between the images and the viewer, Horn manages to engage a questioning about space and time, while positioning photography as a central part of this challenge of perception. The effect her photographs produce on the spectator is close to that of stereoscopic images as described by Suzanne Holschbach: «Contemporary description verify that the «visual desire» that arises when viewing stereoscopic photographs lay in the feeling of immersion: The outside world disappears in favor of the space of an image, which is experienced as a real space. […] the observer is in no way merely a passive recipient of images of the outside world, rather the images are created in the visual process».25 Roni Horn forces the spectator to literally dive into the photographs and recreate in his mind a composite of the two images he is facing. Only through this mental gymnastic will he be able to grasp the whole picture.[…]

22 – p.41 MERLEAU-PONTI, Maurice. The World of Perception. New York: Routledge,

1st édition, march 2008

23 – NIEDERMAYR, Walter. Civil Operations / Zivile Operationen. Ostfilden – Ruit: Dr. Cantz’sche Druckerei, 2003 – p149. «Listen to your mountain». François Xavier. Baier

24 – http://www.nordenhake.com/php/artistsExhibitions.php?id=15

25 – HOLSCHBACH, Suzanne. «Continuities and differences between photographic and post-photographic mediality». Photo/Byte | http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/photo_byte/photographic_post-photographic/print/

Perception, Lies and Reality: Time and the process of drawing with light

Jun 04, 2017 - Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup

Time and the process of drawing with light

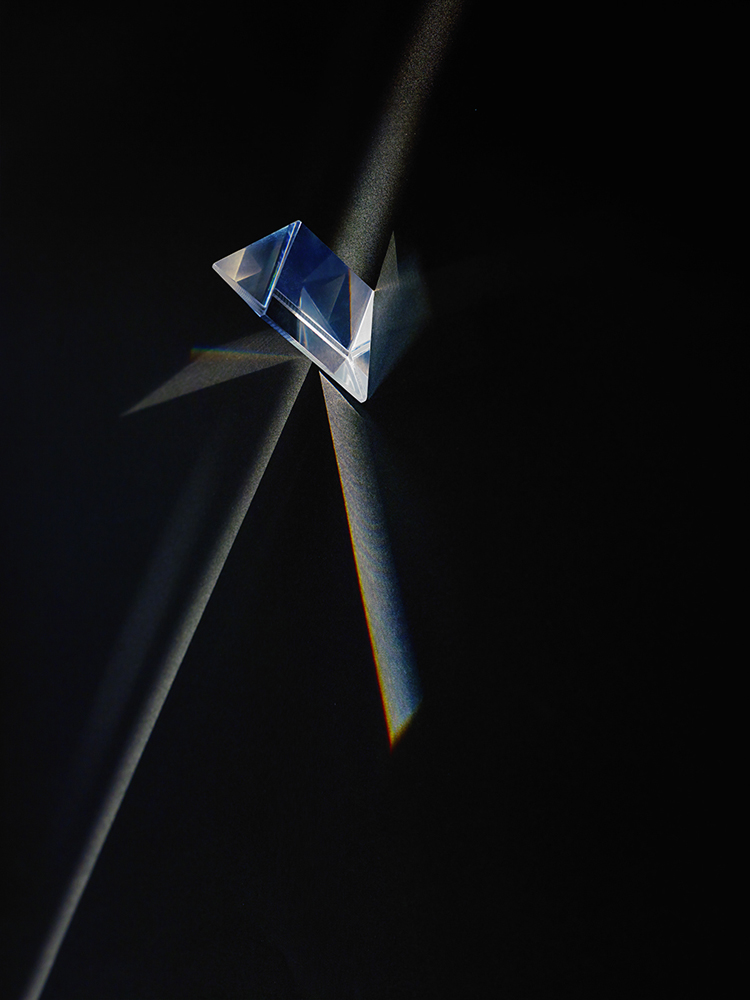

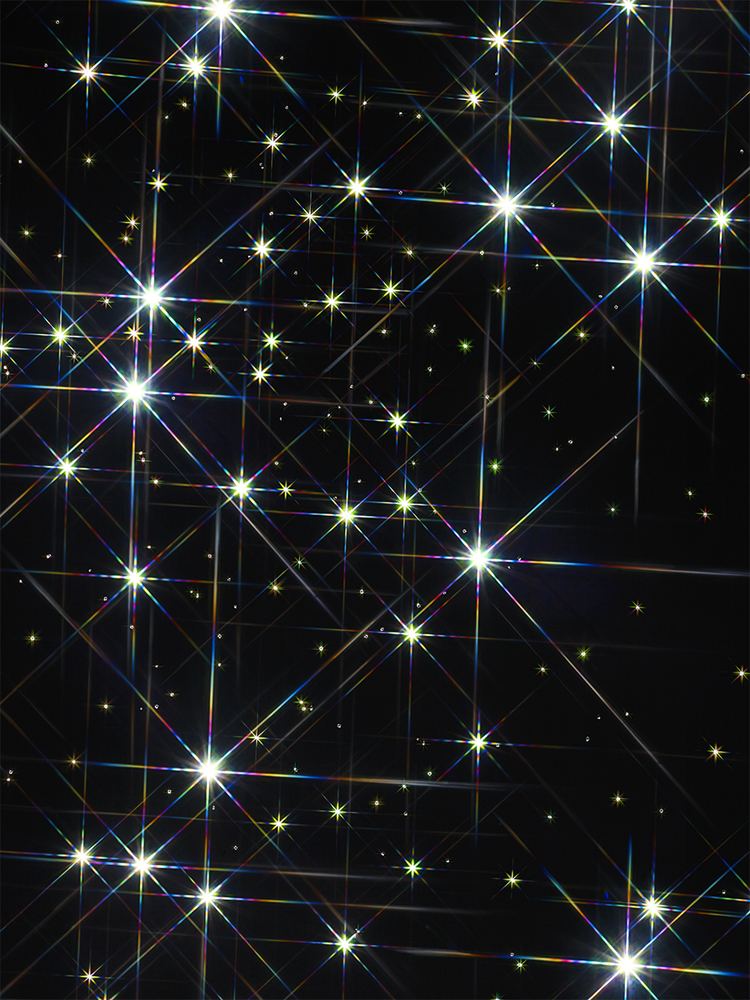

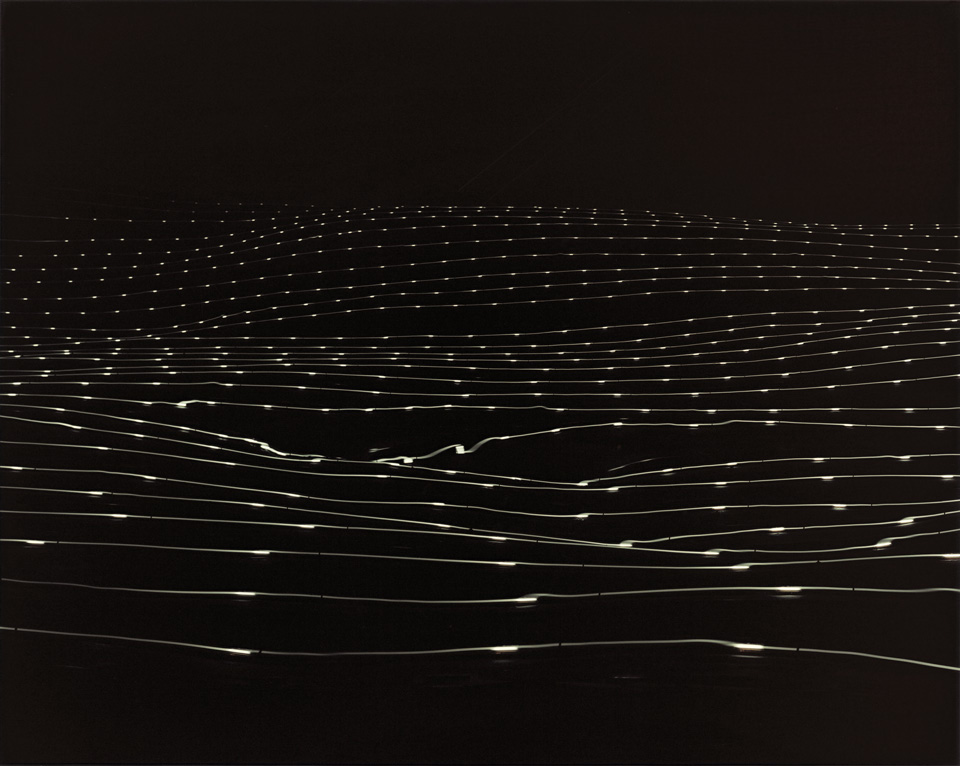

[…] This category of images is more directly concerned with time, and experimenting with the process of photography. They are images, which have a closer connection with the exposure that was necessary to fix the image.

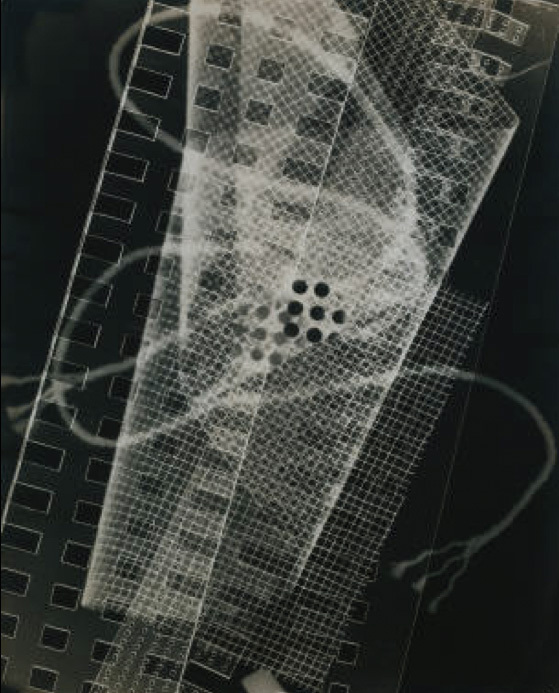

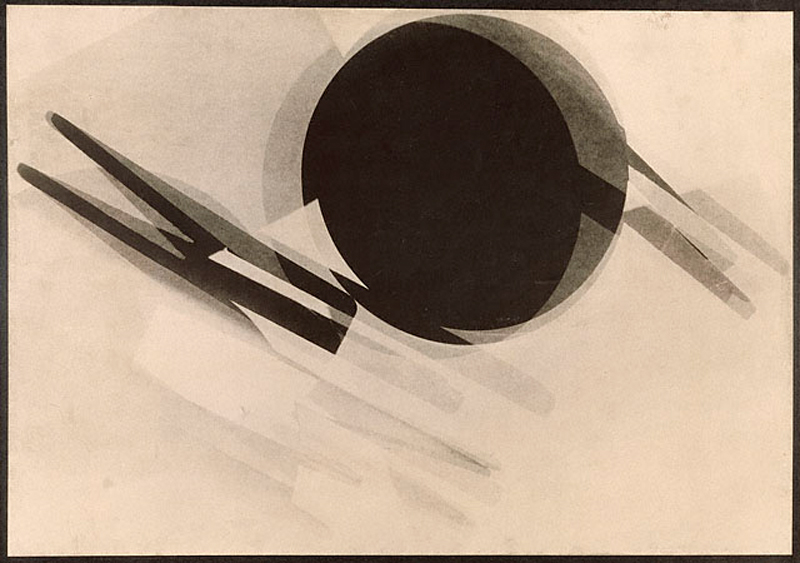

One must here recall the work of László Moholy-Nagy and his conception of «drawing with light». He experimented with the notion that «photographic images – cameraless and other – should not deal with conventional sentiments or personal feelings but should be concerned with light and form».19 He aimed to bring into photography a new notion, diverting from the conception that photography relies on a reproductive mechanism with an artistic twist. He wanted to reinstate the medium (chemically light sensitive surfaces) as a central element of the photographic practice, an element often disregarded, the main concern having been set on the apparatus (the «camera obscura»). László Moholy-Nagy regretted how that negligence had put aside new possibilities of representations, in contradiction with the traditional idea of photographic imagery following the laws of perspective and how objects reflect or absorb light. Rather, he thought that exploring the chemical process of recording light – with the help of the camera – could have led to new visions, to the perception of phenomena invisible to the bare human eye: «Just one of [photography’s] features – the range of infinitely subtle gradations of light and dark that capture the phenomenon of light in what seems to be an almost immaterial radiance – would suffice to establish a new kind of seeing, a new kind of visual power. […] Photography is the first means of giving tangible shape to light, though in a transposed and -perhaps just for that reason- almost abstract form».20 Indeed, the photographers shown in this category, unlike the advocates of the decisive moment, make use of time and its infinite dimensions to reveal (in photographs) light phenomena otherwise invisible. […]

Hiroshi Sugimoto uses a similar process – long exposures- in his photographs of movie theaters, in which he exposes for the length of the film projection. The images give us a metaphorical vision of the passing of time, taking the counter point of the «decisive moment». Light and time – the fundaments of photography – develop into the central subject of the image and a blank space. The whiteness of the screen, in which the evidence of a movie playing still lingers, stands against what remains immutable in the surrounding landscape: any non permanent details (cars driving by, people, etc.) have been removed by the long exposure. In Sugimoto’s own words: «too much information ends up in nothingness, emptiness».11 We are seeing on one side the permanence and on the other the moving; two absolutely opposite dimensions of time. Light, time and their influence on what becomes visible are here once again essential. Something similar happens in Sugimoto’s seascapes where, due to long exposures, the waves disappear and give way to a surprisingly still field of water. The archetype of photographic recording, the capture of the totality of an image in one single fraction of a moment has here been replaced by another temporality, in closer relation to the process of fabrication of a painting or a sculpture. On another level, Sugimoto himself sees these images connected to an ancient time, insinuating a journey through history: his goal was to give the contemporary spectator a vision similar to the one experienced in ancient days, hundreds of years ago. The absence of anything but water and air make it impossible to date the photographs, thus they become timeless and permanent. The spectator, drawn in, loses himself within the picture, and is set free from the strings of time.11

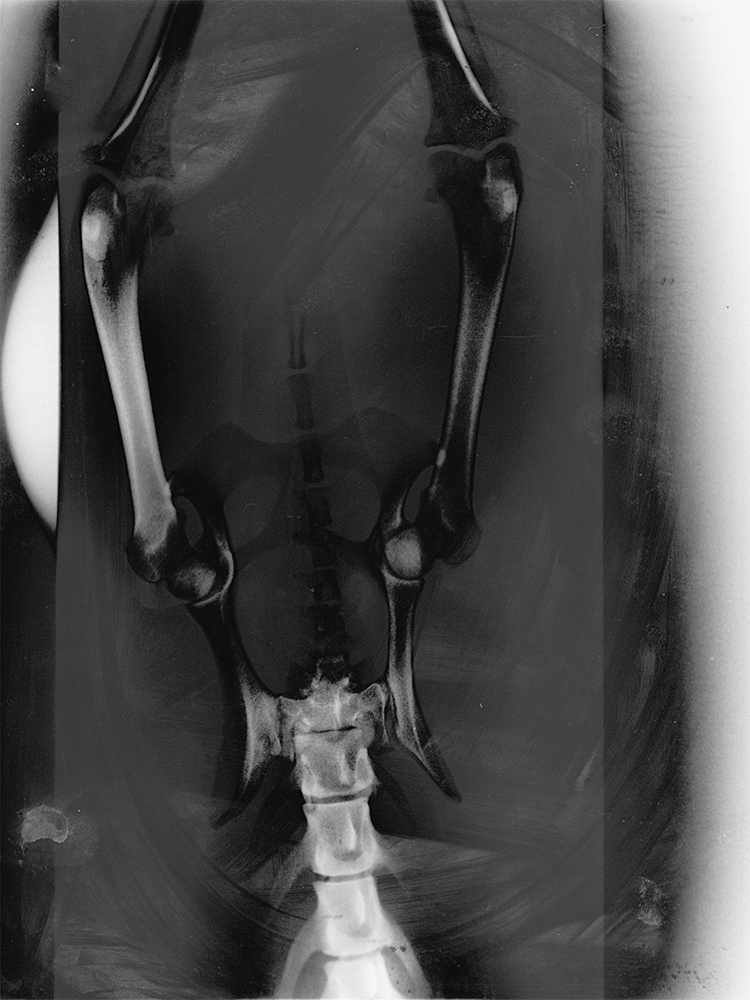

Thomas Flechtner, in his series «Walks», even more actively participates in the «drawing». He shapes himself the ephemeral traces that are left behind, as he walks through the landscape. These traces, which vanish as soon as they appear, have however left a continuous mark on the photograph. Flechtner draws out the underlying ghost lines enclosed in nature. This enables him to expose the viewer with a new outlook on the landscape: the figurative details and the perspective have vanished, leaving only the lines that follow the curves and undulating hills he travels through. Not only does the resulting image evoke a topographic map, it reveals the very structure of the hills – as an x-ray would with the skeleton of a body. Photography becomes here again a way of recording and bringing to light something invisible to the naked eye. It is also an acknowledgment to the flow of time, which makes one recall Lyle Rexer: «the very idea of a still photograph is artificial and abstract, involving a severing of particular objects from the flux of forms and instants that make up the continuum of time».21 […]

19 – p. 394 ROSENBLUM, Naomi. A World History of Photography. New York: Abbeville Press,

third edition 1997

20 – TRAUB, Charles H., HELLER, Steven and BELL, Adam B. The Education of a Photographer.

New York: Allworth Press, 2006 – p.199-200 «Unprecedented Photography». Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

21 – p.185 REXER, Lyle. The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography. New York. Aperture, 1st edition June 30, 2009

Perception, Lies and Reality: Multiple exposure

Jun 03, 2017 - Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup

»Blank«, the body of work presented in the Artist Feature this week, came out of my master thesis research, which addresses the notion of truth and perception in photography. I will thus be posting a few short excerpts from this essay throughout my take over of the artist blog.

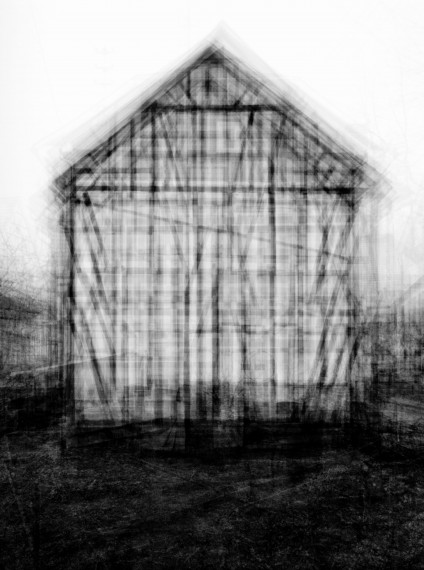

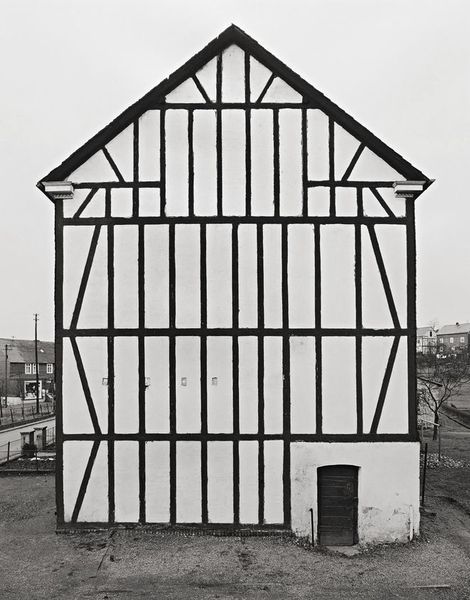

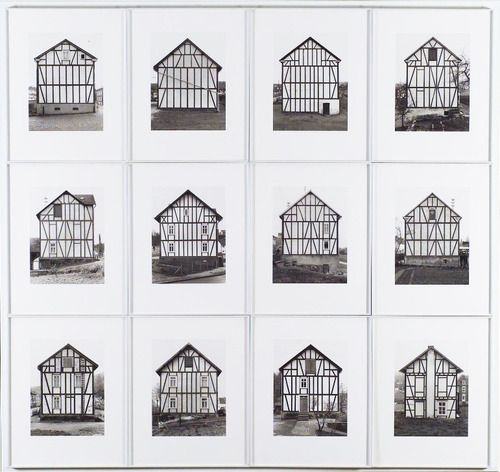

Multiple exposure

[…] This category is composed of photographers, who use multiple exposures or the layering of various shots in one single image. It is a way to show both some sort of permanence – at the core of every being or object – and a state of perpetual change. It illustrates to a degree Barthes’ sudden and utopist urge for the image and the self merging in the photograph: «what I want, in short, is that my (mobile) image, buffeted among a thousand shifting photographs, altering with situation and age, should always coincide with my (profound) «self»».12 It is a way to search for the enduring things that underlie all individualities or categories, as though there are similarities at the basis and differences only in futile and ephemeral details. We are faced here with a kind of «invisible»: that of the core of the self or thing – which emerges through these composite portraits – and that of the ghost like resemblances that appear in the photographs. These images find themselves radically opposed to the idea of photography as a mirror of the world: they bring together numerous moments diverging in time and space in an attempt to give a vision closer to another reality. They allude to a truthH that cannot be found in one well-chosen moment frozen in time, rather to one that undergoes perpetual change. It is only by bringing together diverging moments that we may hope to grasp the essence of the actual state of things.

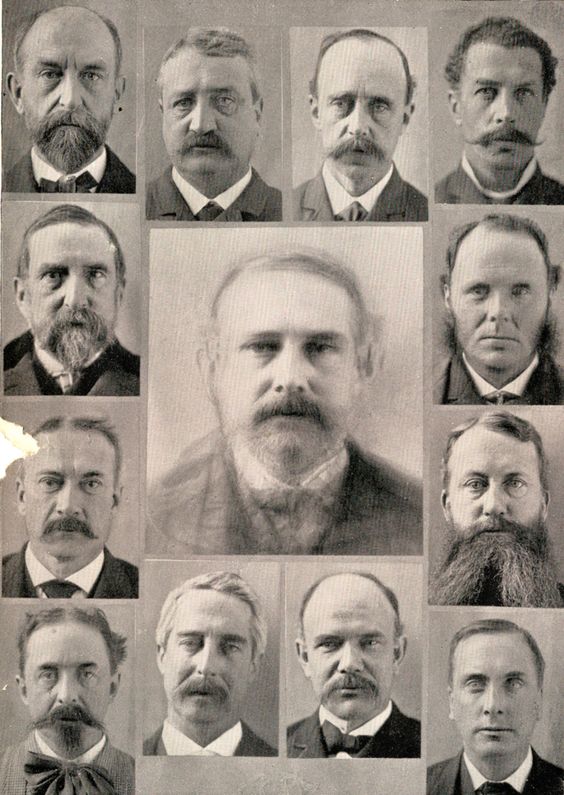

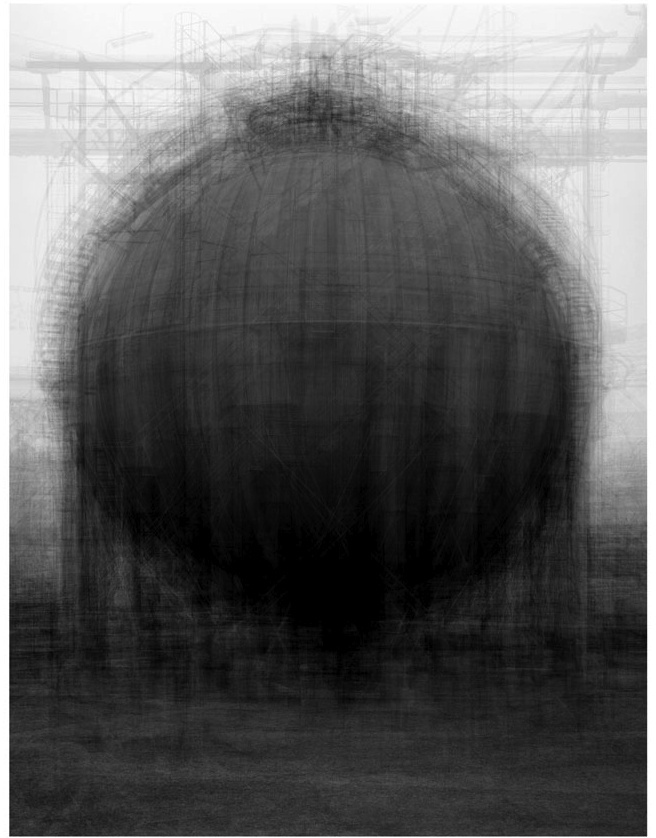

The photographs of Idris Khan are a very good example of the idea that there are types of individualities and objects, which become clear only through a layering of images. Using the images taken by Bernd and Hilla Becher, Khan’s photographs seem to draw further attention to the infinite richness of variations of the functional architecture displayed in the original photographs. The images resemble sketches, displaying the multiple attempts needed to achieve a final shape, hinting at the great amount of constructions built over time. They have no definite outlines and still there seems to emerge a common shape at the basis of all the layered images. They become a new way of creating typologies, and allude to Gamboni’s observation that «superimposition was seen to have heuristic value and might even enable the reconstitution of the authentic image of a historical character through identification of the common features of [this] surviving portraits».13 It is truly surprising how all the trivial details (elements in the background, fine details on the surface, etc.) have disappeared in Khan’s images, to leave only a black shape against a grey background. The details so important in Henri Cartier-Bresson’s vision of the decisive moment have lost all consistence and left room for a more general and permanent interpretation. Khan is indeed reenacting what Francis Galton and Arthur Batut did with people at the end of the 19th century when they superimposed images of inhabitants of various villages, families or people with specific personalities in an attempt to outline a «type» of people in these families, tribes, races, etc. […]

H – Truth: honest facts, things as they are | in accordance with facts or reality | accurate, exact,

no interpretation or personal intervention

12 – p.12 BARTHES, Roland. Camera Lucida. London: Vintage Classics, 2000

13 – p.162-163 GAMBONI, Dario. Potential Images: Ambiguity and Indeterminacy in Modern Art. London: Reaktion Books, April 4, 2004