Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

Q&A featuring Broomberg & Chanarin, Donald Weber & Shailoh Phillips

Feb 25, 2019 - Gita Cooper-van Ingen

We discuss the first year of the KABK’s new MA program in Photography & Society with Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, Shailoh Phillips and Donald Weber.

“Students of media are persistently attacked as evaders, idly concentrating on means or processes rather than on ‘substance’. The dramatic and rapid changes of ‘substance’ elude these accusers. Survival is not possible if one approaches his environment, the social drama, with a fixed, unchangeable point of view – the witless repetitive response to the unperceived.”

– McLuhan, Marshall, Quentin Fiore, and Jerome Agel. “The Medium Is the Massage”. 1967. London: Penguin Classics. 2008. 10.

Could you give us a few comments on this quote by Marshall McLuhan in relation to your ideas behind this Masters in Photography & Society? What are some of the ideas behind your approach to un-learning and why is this important for the MA program, what kind of people are you looking for?

I see photography being altered through technological systems of seeing, such as automated technologies of image production and distribution, machine-to-machine based image culture, and a global culture of amateur photography, all combined with the changing economic capabilities of traditional media. Amongst all this, society’s capability to render this new visual language as a meaningful participant in everyday life has become of utmost importance. Visual culture is changing, and it’s imperative we keep up. With all this in mind, it certainly raises many questions for the identity, purpose, and possible social impact of (documentary) photography. My main critique of photography is largely related to its own disciplinary nature, and how regimes of value construction, awards and capitalization have such outsized influence on the practice.

I see a discipline where students and young photographers are largely trained instead of educated, where the systems of awards and festivals in which professionals participate are significantly shaping their understanding about what is considered “good photography.” Amongst all this, the image acts as a mechanism for the ideological reproduction of the status quo, and it becomes harder and harder to expand the possibilities and relevance of photography.

So, thinking through all these critical layers, we want to position Photography & Society to help contribute to the conversation and debate of what photography can be in this rich landscape of images. Our program sees photography as a practical medium, while simultaneously asking why photography matters. We really want to create a space where the critical and reflexive opening up of the discipline can happen, engaging with other cultures. Firstly, we believe in the necessity to engage with other established disciplines, connecting photographic discipline to broader ontologies and strategies that can help to significantly enhance photography’s impact, while also informing photographic decisions for the student.

Secondly, this ‘extra-disciplinary’ approach of reaching into and towards different kinds of knowledge, such as communication and media, empowers possible photographic strategies. With Photography & Society, I really believe that photography is communication, and by understanding critical knowledge of the media ecologies within which documentary operates, we can further strengthen the capabilities of the photographer. For me, it’s very simple. By embracing a broader form of visual engagement, photographers can emancipate themselves from well-worn tropes of storytelling in order to further create compelling means of visual communication. I prefer to think around the ideas of (un)-disciplining and (un)-learning photography. This approach can then advocate for radical change in the discipline itself by looking into possible strategies, which aim to empower documentary as a field of knowledge and practice of social engagement.

In Photography & Society, we do not see the role of photographer as submissive to market forces, but rather we want students to come with determination to impact the world in ways that would make it a more just place, while at the same time being equipped with the knowledge, skills and understanding that enable the photographer to do so.

Again, really see it as simple logic. If we can question the Identities that are bound to current disciplines and allow them to shift, then knowledge relevant to documentary could become response-able. A starting point should not be who we are but what we want to achieve – and once we know this – who we want to become. With this in mind, if you are interested in opening yourself up and looking for ways of productive collaboration with culture and willing to counter the mechanical expertise and technical formalism of modern society, then we would love to have you at Photography & Society! That’s because we believe in educating photographers who have both the knowledge and awareness to make critical decisions, are able to reflect on conditions of photographic production, and just want to engage with the world.

What were some of the more important insights, highlights, excursions, routines etc. for you and the students so far?

The first semester of study is really about loosening the framework of your practice that you came in with. We don’t ask you to discard it, but we do want you to consider it, and to question it. Questions lead to further questions, and in return, a deeper sensibility of what you’re really here to do. It is a Master’s education, after all.

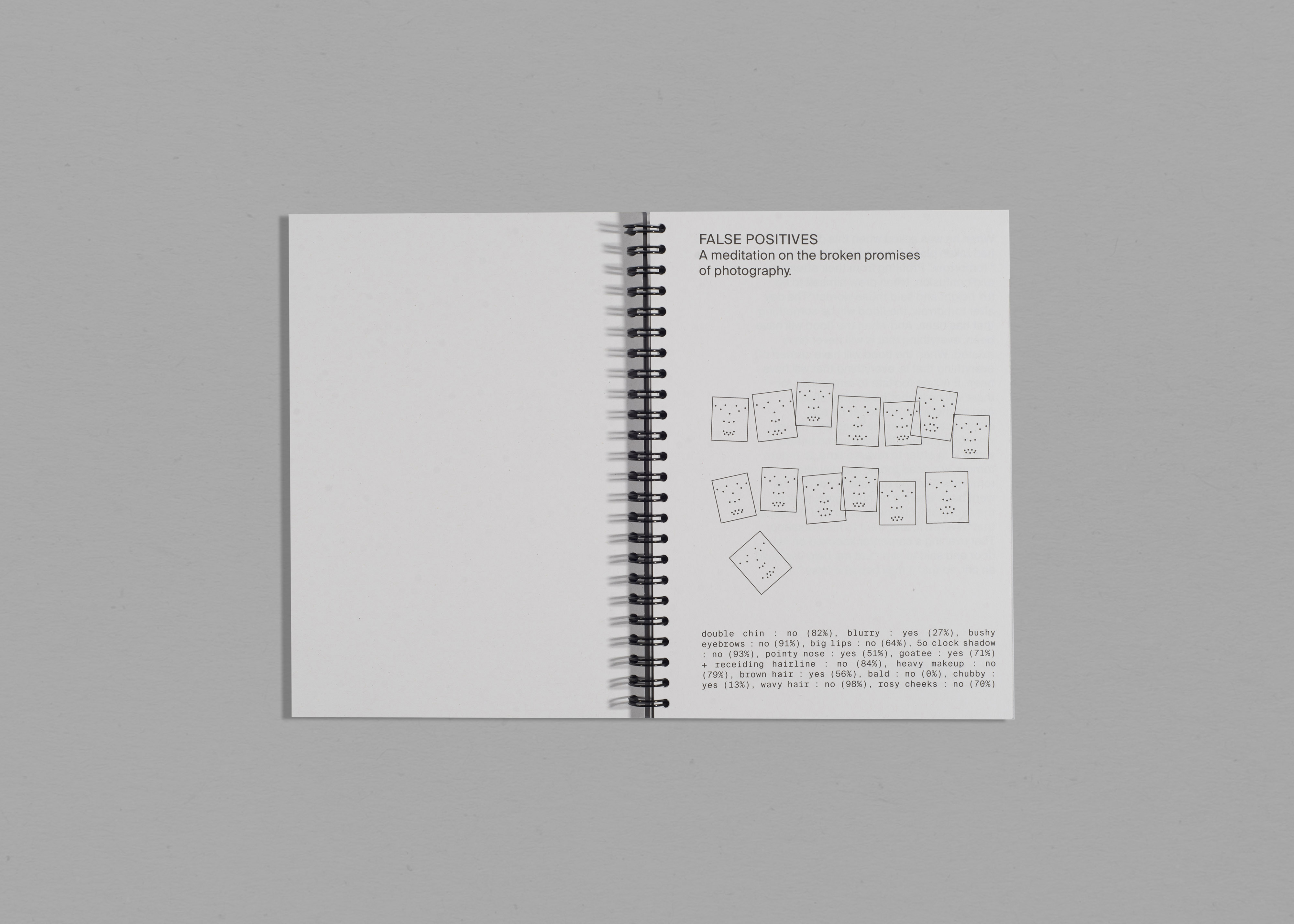

Therefore, we really wanted the first semester of the program to be very intense, very rich and at times invite existential questions from the students. The first half, in Adam’s studio which we called The Liquid Image, the students were confronted with a simple question: What can photography be? We wanted students to be exposed to multiple ideas around the medium, but not getting lost in endless discussions of ‘photography is dead, or is it:’ that ship has sailed. It’s really about the evolution of visual culture, so in this studio we want to engage students to make explorations further afield, to begin to slip into other disciplines. So, for example, how does blockchain technology affect the idea of an original in photography? What about the poor image, the amateur, the idea of the medium as pleasure? We also looked at the gaze and race, something which cannot be overlooked at all, especially in an economy of images where machines are the predominant mode of seeing and are deeply embedded in practices of power. Lots of things! This was a 6-week course, and the students were obliged to constantly be making, making, making and responding to critical issues in visual culture today. We summed this studio up with a student-led publication that they called ‘False Positives’, which looked into the “broken promises of photography” (while seeking to create new promises).

There was a workshop led by Carlos Spottorno, who helped us understand and visualize the impact of photography and to seek alternative platforms to share photography works. Through a local organization in The Hague, called Justice & Peace, we collaborated with an Egyptian human rights defender on a small action campaign directed towards the lack of housing in The Hague. Students also are encouraged to collaborate with other departments, and this year they created a small project with Master students from INSIDE (Interior Architecture), all the while fervently working, reading, gathering, speculating and making.

A benefit of being located in The Netherlands, is that there are lots of interesting people constantly passing through the country, so we try to invite as many people as possible (but not too many, we must stay focused too!) These guests are invited to spend intimate time with students, and gain insight into each other’s’ practice.

In the second semester, we have transitioned from working really intensively on smaller projects, and move towards a 12-week project situated in a community called Duindorp in The Hague. This studio, which we call Platforms for Visual Resistance, is being conducted with Oliver Chanarin and Henk Wildschut. The goal is to engage questions of audience and the role of impact. It’s a collision where the principals of both ‘photography’ and ‘society’ (and all that they stand for) are put into practice. To get to this point, Andrea Stultiens led the previous studio called Photography as Social Practice, which confronts the student with the need to seek and understand the level of responsibility, and to use photographs to not speak for, or about, but with others, and thus attempt to transcend spectacle and ‘otherness’.

In this program, it is important to understand that both the practical action – the making – and theoretical reflection – the thinking – go hand in hand. One cannot exist without the other, action and thought must be inextricably linked. We have a very engaging philosopher of photography, Ali Shobeiri, who explores the notions of beauty in photography. He asks what is profane, and what is abjection? Ali takes students and looks into the ideas of vulgar art, kitsch, porn, abjection, profanation, and ugly humour. This program is dedicated to the aesthetics and politics of taste in photography. In Thomas Bragdon’s theory program, he engages with students to encourage them to speak and write about issues like the ethics and politics of migration, or investigate non-violent action groups that proclaim human rights without state-protection, or question the truth-value of photography in the latest developments of the media. Students have visited the members of the action group ‘We Are Here’ whose actions interlink the issues discussed in class.

What can prospective students already expect and what should they know before considering to apply?

We have two deadlines – March 1 is our priority deadline, and (especially if you are a non-EU student), and May 1 is the final deadline. Keep in mind we like to create an intimate group of students that feel safe, and have a desire to explore and take risks. Therefore, during the admissions procedure, we will invite prospective students to come to The Hague and meet the current group of students, as well as interviews with Faculty, tour the school, check it out and see if this is really the place for you. It’s about commitment – we want to know you’re as dedicated as we are. All the information to make an application is readily available on the KABK website.

Photography & Society is a rigorous program, so we really ask you to come prepared to engage with your practice as it stands in its present condition. The program is structured in such a way to enable you to open up questions of practice so that you can begin to formulate a set of circumstances that can allow you to see what you choose to bring forward, to carry with on, but also to deeply examine what needs to get left behind.

Be ready to critically address your position within photographic practice, and have a strong desire to move beyond the bounds of the discipline and start looking at photography as an extra-disciplinary practice. In other words, Photography & Society is very much an incubator where questions of responsibility, political engagement and experimentation are allowed to be considered, chewed apart, reformulated.

I like that we are both confrontational and interventional. It’s not about making artworks destined for the wall of a collector’s home, but rather we want photography as a way to confront power structures, and to help create a different set of tools to understand and confront the world. Our program is responding to all the new social and political conditions that are rapidly forming in the 21st century, and so we are looking for students who want to urgently contribute to a new set of possible practices.

For further information on how to apply please visit the KABK website.

Can you show us a selection of the current first year’s works?

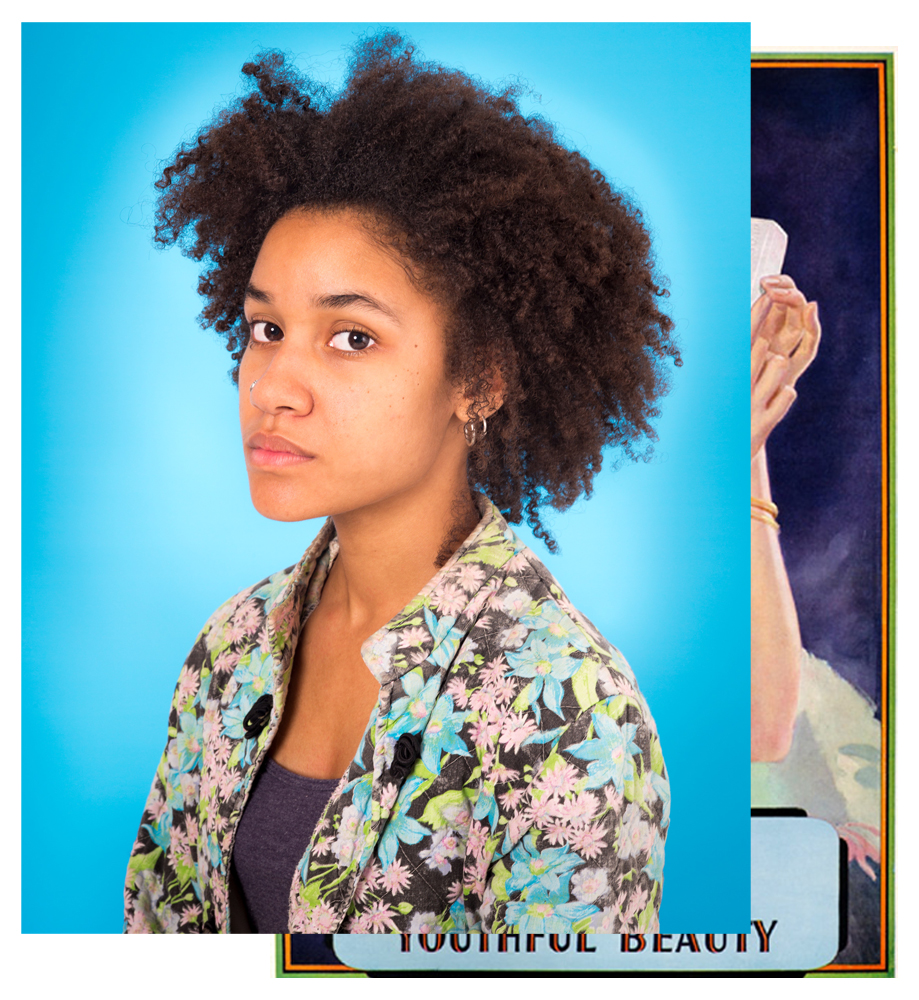

Ana Nuñez Rodriguez

In my work I focus on the relationship between the individual and the environment and how this affects at an emotional level, producing images full of fantasy and mystery that reveal a very personal vision of the social landscape. After living in Colombia for the last few years, my most recent projects have been influenced by how European and Latin America reality converge also within my life, proposing games of contrasts full of irony where I interrogate myself about identity and politics and their complexities marked by the collective memory and the cultural heritage.

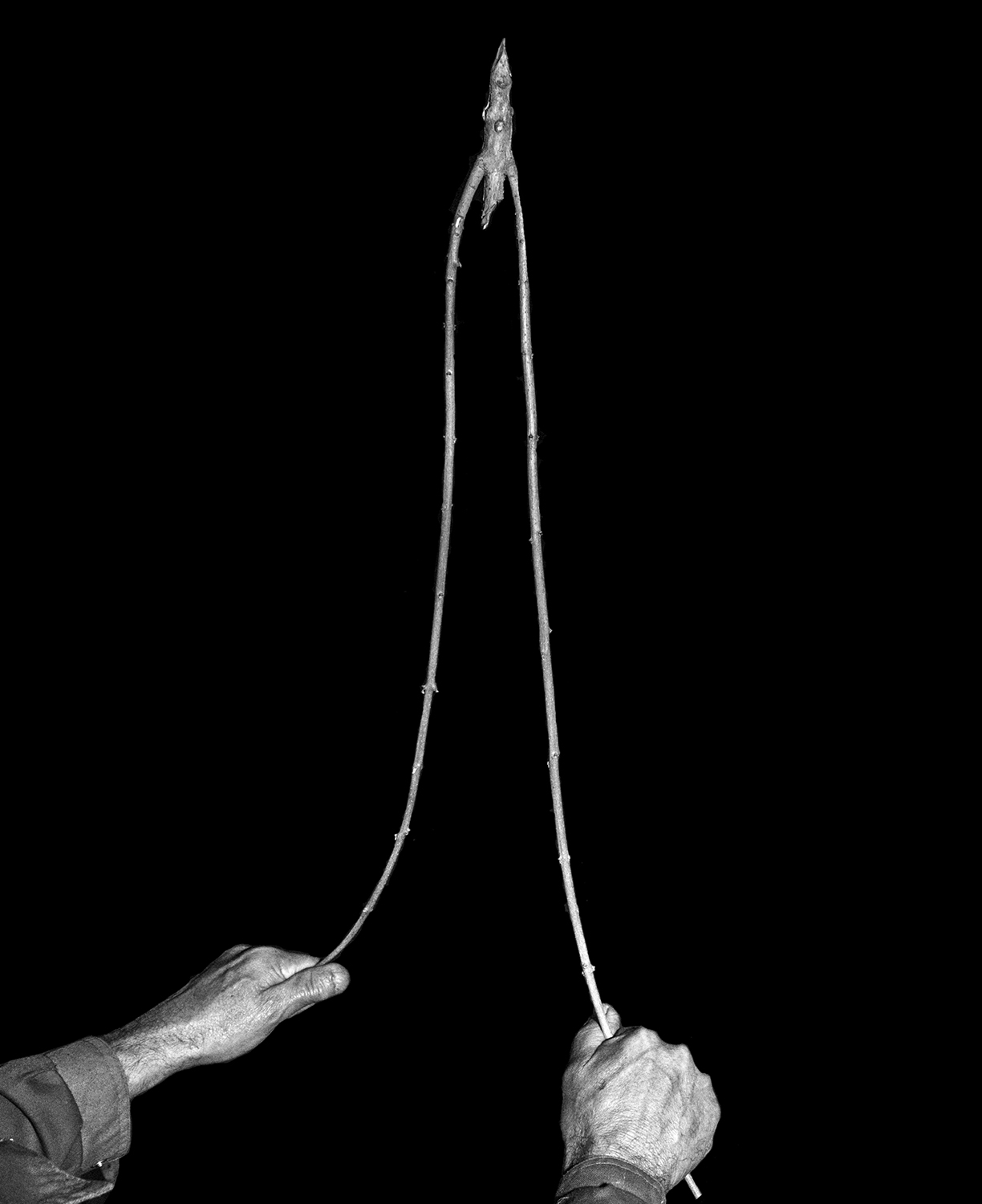

Shadman Shahid was born and raised in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Prior to joining the Masters of Photography at KABK he was teaching Photography and Multimedia at Pathshala South Asian Media Institute for three years, where he also acquired his Professional Photography degree from in 2015. His work is about the precarity of the corporeal and the spiritual human conditions in contemporary society. His photographic methodology walks the line between documentary and fiction and usually, in his work, the content drives the aesthetics. His photographic works have brought him a few accolades including World Press Photo’s Joop Swart Masterclass, BJP ones to watch in 2016 and Burn emerging photographer of the year in 2019.

Olga Roszkowska is a visual storyteller, who through photography and video communicates issues of displacement, spatial identities, unequal exchange and extractivism, currently experimenting with visual strategies for land-grabbing resistance and reflecting on different human and material criticalities. Since 2016 she’s been conducting documentary-research project „Richtung Venezia” in Shuto Orizari- world’s first autonomous Roma municipality within Skopje, Macedonia- aiming to investigate the influence of contemporary nomadism of its residents on architectural expressions and practices of dwelling.Co-founder of Spółdzielnia „Krzak” – collectively run garden and cultural space in Warsaw, PL, which serves as a platform for participation, commoning and exchange through translating environmental care into post-artistic practices.

Mads Holm (b. 1990, Copenhagen) has previously studied Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at International Center of Photography in New York and holds a BA (Hons.), First Class degree in Fine Art Photography from the Glasgow School of Art.

In my search for new pictures and presentation forms I continue to feel ethically challenged by approaching photography both as a representational and aesthetic medium. I question the potential for impact of the photograph when appreciated primarily for its aesthetic features. In the meantime I struggle to carry forward the picture as “report” with qualities relying less on form and more on its reference to a social reality. This dilemma is what I currently investigate in Photography & Society.

Chris Becher is an author of documentary work. His work explores through different strategies how systems of power shape the identity of individuals or groups of people by means of photography, text and video. He holds a diploma from the Academy For Media Arts Cologne where he graduated in 2016. His work has received various awards and was lastly shown in the Kunstverein Wolfenbüttel; Haus der Photographie, Deichtorhallen Hamburg and NRW-Forum Düsseldorf. In 2017 he was invited as an artist in residency by the Goethe Institut to work in India.

What would you say the various teaching approaches this course offers particularly, is there a particular focus?

We are very focused on peer-to-peer situations. Our program is based around the idea of the encounter; that every encounter leads to others, and are able to be re-traced.

How do you structure your teaching?

Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin: We are very focused on peer-to-peer situations. Our program is based around the idea of the encounter; that every encounter leads to others, and are able to be re-traced. Nobody ever tells you what they really think of your work. As an art student it is almost impossible to get good feedback, and once you leave college it gets worse. As a Photography & Society student at KABK, you will learn to give and receive feedback in a safe environment. You will learn the necessary skills to listen, reflect and find the right questions. Honest and constructive feedback is at the core of our program.

Your work (and PhD research!) looks at power structures and how they operate, and what consequences and traces they bring. In what ways have you found The Hague a useful location to start this academic program?

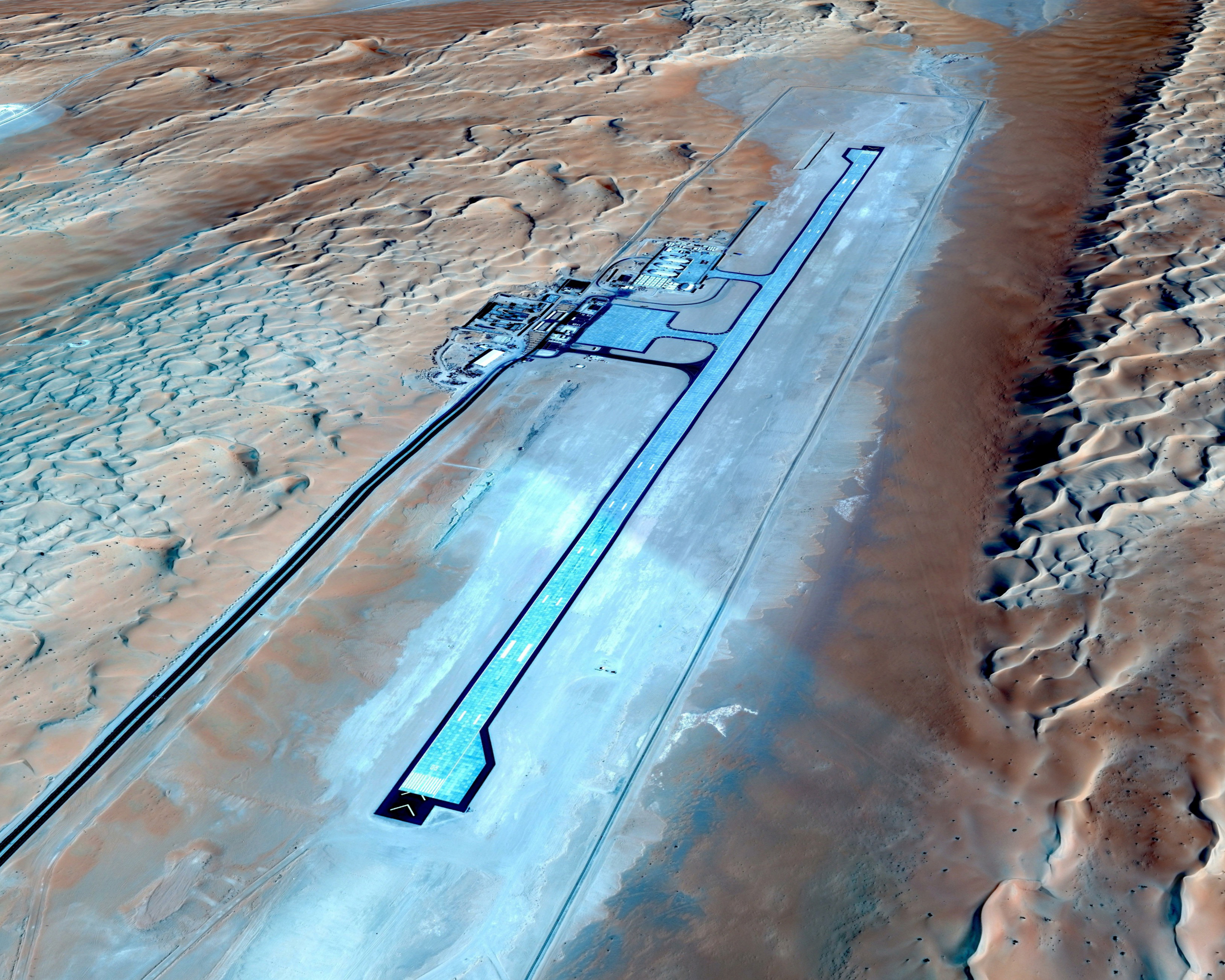

Donald Weber: We are very fortunate to be situated in this city, as hidden infrastructures of power are everywhere. The Hague materializes the values of democracy and justice, and yet the very economies that promote this ideology are embedded in the ecologies of war. The Peace Palace, International Criminal Court, Europol and various Tribunals are all situated within the city limits. To situate a Master program that is designed to confront power through the un-disciplining of photographic practice, we could not be in a better location. The Hague is governed by – and inhabits – the propaganda of security, internationalization and diplomacy. Here, the European project presents itself, as very fertile soil of exploration for any student who wants to question the conventional norms of art, to participate in a socially engaged and responsive practice, and to challenge and map the infrastructures of power.

Amongst the many things you do, you also teach on the new MA Photography & Society program. Can you describe your approach and work in Artistic Research and how that feeds into rethinking our positions within the field of photography?

Shailoh Phillips: In this program, we offer the possibility of working with multiple research methods, such as multimodal ethnography, design fiction, or artistic research. There is not a strict formula of ‘how to do research;’ we expect you to come with your own questions and urgent issues based on your practice. As described by Estelle Barrett and Barbara Bolt, artistic research is “practice-led inquiry that draws on subjective, interdisciplinary methodologies that have the potential to extend the frontiers of research.” This means cultivating the willingness to create your own tools and methods, to question your premises and ways of understanding. To unlearn the things you are most familiar with and dwell in a place of not-knowing. To experiment, explore and allow your practice to be informed by others.

“Art is not a mirror for society, but a hammer with which to shape it” (Vladimir Mayakovski).

This is the slogan of the artistic-activist group Tools for Action (founded by Artúr van Balen) that I am working with, using inflatable sculptures in the context of protest movements. This quote which is obviously at odds with its accompanying visual: the hammer to shape society is a mere toy, an arresting ploy to generate collective action — soft, portable and wrinkly when deflated, large, taut and conspicuous when filled with air. Tools for Action draws on the paradoxical qualities of inflatable objects: their simultaneous mobility, fragility, and impressive sizeInflatables are floating and light-weight tactical tools, ideal for sending political messages, disrupting protests and blocking streets. However, the political orientation of such tools are not fixed; indeed, they are filled with nothing but air, empty signifiers devoid of direction or content. As such, I do not see myself as a photographer, but as someone who creates photographable moments, assuming that there are enough cameras around to ensure the compelling scenes will be shared as images.

Although my own practice borders on activism, I do not expect the same of students. What is crucial, however, is to experiment, explore, question and allow your practice to be informed by others. Curiosity, intellectual generosity, a broad frame of reference, and an embodied way of listening and thinking are things that I bring to the classes, all intended to cultivate the courage to take risks and think through the ethical and conceptual dimensions of your work. One of the important parts of this is the practice of writing. For photographers, this is often a challenge, so we spend time on practicing creative, journalistic and academic writing skills. In my experience, making your thoughts explicit and sharable also feeds into the images you create and helps you to position yourself, as well as find out what you would like to contribute in shaping our world.

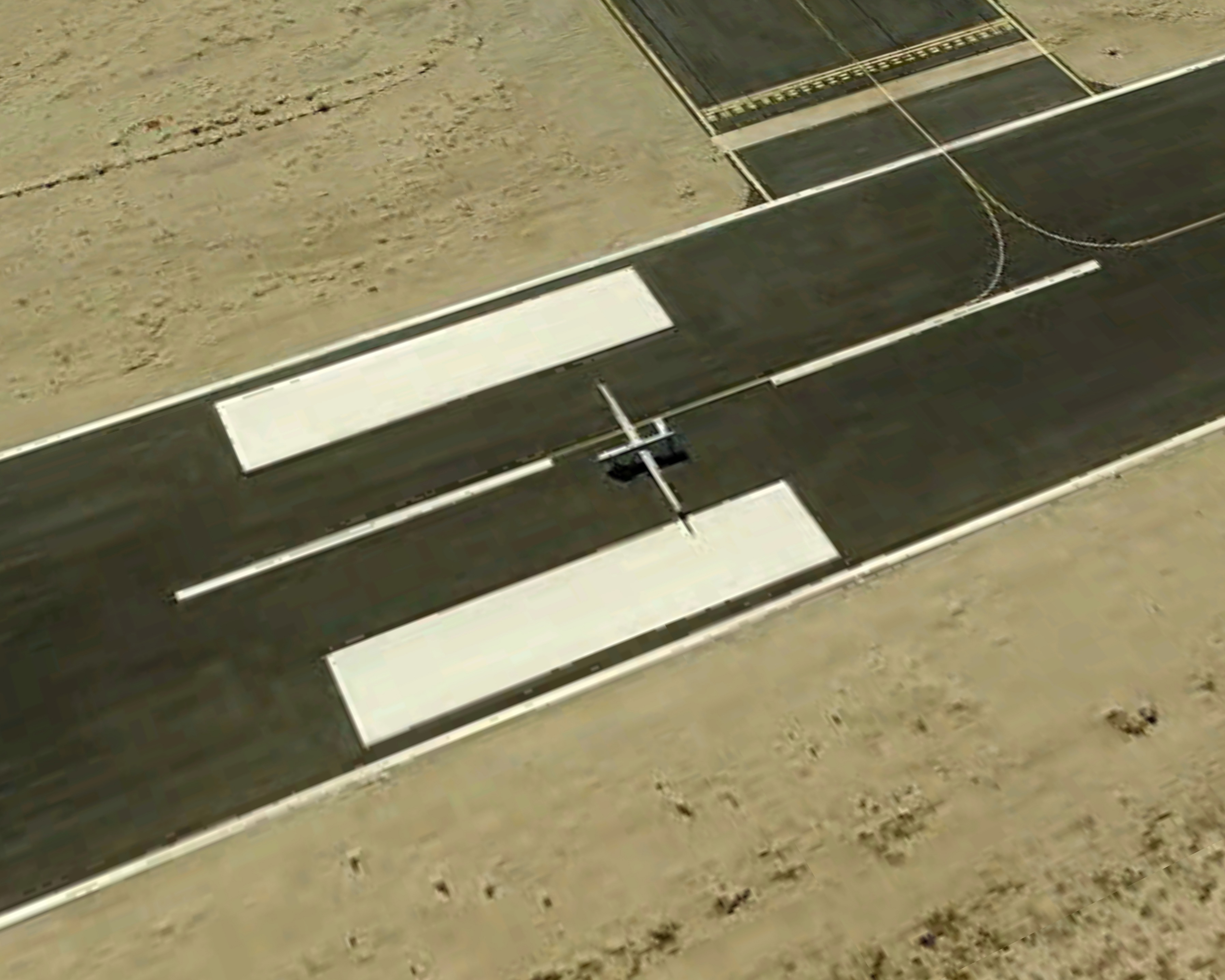

1/4 El Martillo, a 12 meter silver inflatable hammer as an unconventional symbol for climate justice, initated by Artúr van Balen and Jakub Simcik and sent to be used in Mexico City, 19.10.2010, Photographer unknown.