Artist Blog

Every week an artist whose single image was published by Der Greif is given a platform in which to blog about contemporary photography.

Railroad Landscapes: An Illustrated Transcript of a lecture by John Sanderson

Apr 15, 2020 - John Sanderson

Railroad Landscapes

An Illustrated Transcript of a Lecture by John Sanderson

Presented at Lake Forest College, Illinois

Saturday, April 9, 2016

Introduction

Greetings to the Center for Railroad Photography & Art. I thank you for the invitation to speak here among a group of artists whose work has influenced me along the way. Being twice awarded a docent scholarship to attend the conference has allowed me the freedom to create work that I will be discussing here tonight and on display at Glen Rowan House. I also welcome Joe Stroppel, a recipient of the docent scholarship this year, who was a student during my Art on the Tracks film workshop at the New York Transit Museum last Fall. This workshop was an extension of my Railroad Landscapes exhibition which is on display at the museum. Joe – I hope you will absorb a lot here, I certainly wish I had this experience at your age.

I’m here to shed some light on how I came to develop the Railroad Landscapes project, and provide insight into how these photographs function. The first half of my presentation will be a discussion of my project. The second half will be a narrated journey of railroad landscapes from my home in New York to the farthest west I’ve so far photographed for this project, Glacier, Montana.

I’m often asked why there isn’t a train in these images. For a while I would answer by stating that it would change the composition dramatically or de emphasize the surroundings. I realized recently the best answer to this question was more oblique: to explain how I came to leave the train out, which is where I will start today.

Trains are where I started. Beginning photography at the age of 13, I was driven – literally and figuratively – to photograph the steam railroads in eastern Pennsylvania. I knew them from my youth when car trips from our home in New York City brought me to these mysterious machines, machines which seemed to hold human attributes – they struck me as alive even in repose. The hisses, clicks and clanks of the feedwater heater, or release from the poppet valves exuded excitement. Movement from their visible gears became a ceremony for me – the fact that men were somehow in control of these Beasts seemed implausible, for containing its power seem unfathomable – in my wondrous mind the steam locomotive engineer seemed to hold powers beyond the bounds of mere mortals. It was with this wonder that I began shooting the steam trains in Pennsylvania.

Soon after, proximity led me to begin photographing modern freight railroading my neighboring Hudson Valley. While working at Barnes & Noble in Manhattan, I became intimately familiar with the work of O. Winston Link, whose photographs I studied. I found they reached beyond the bounds of documentary photography and struck me on a deep level as a more universal photograph than what I was creating. This work taught me the importance of context, the train is often small within the frame, yet its presence underscores each picture. Link surrounded the train with people, interiors, and the vernacular essence of rural Virginia in the late 1950’s. Because of how Link diminished the train, it grew in importance, and actually reinforced the impact of the train in the picture.

Concurrently my interest in shooting freight railroading began to subside, due in large part to comparing it to the “golden age” of the 1950’s. I also began to shy away from steam excursion photography. My reasons for this were clarified as I prepared this presentation, so I thank you for the opportunity. Events which position the train as an object of adulation are ceremonial in intent and therefore unrelated to their historic role — I wanted to start looking at the contemporary railroad scene in a way that engaged a larger audience. It also struck me as unnecessary to try and beautify in pictures what had been done by so many brilliant photographers in the past, and I was never truly happy that my pictures did them justice. And of course, as I began working with large format cameras, photographing moving objects became difficult — in the end, maybe this is the reason.

So I decided to leave the train out, and embrace the challenge of finding beauty in the landscape independent of its intended use.

A Quality of Absence

What is the meaning of a train in a picture? I think the general public, and we railroad photographers, are conditioned to react against emptiness. Proving the landscape to be populated by the railroad’s activity and for much of American history the train was a companion in times of prosperity, and in the darkest days, an escape to opportunity. As I looked farther back than Winston Link’s work, to photographs from 1860 to 1910, I began to find myself within a tradition of railroad landscape photographers that I was theretofore unfamiliar with. The incipience of railroad photography began in the mid 1800’s with photographers such as Carleton Watkins, William Henry Jackson, and later around 1900, William H. Rau.

Their subject was often the rail lines and infrastructure itself; the ‘conquering’ of the vast American landscape by rail was, at the time, a most industrious feat — more so than the locomotives themselves. It is here where focus shifts from the train to the tracks — within this development, the track’s gesture in each picture supplies the energy, replacing the momentum of the train — more on this later.

In order to better understand the interplay of color and shade on surfaces, and since all these early photographs lacked color, I began to study 20th century American realism in painting. This brought me to the the graphic dimensionality of Charles Sheeler’s precisionist paintings. Referencing industrial architecture, his work’s strict linearization of form, shape and ‘energy of line’ symbolize the subject’s momentum and created, on a flat surface, an internal rhythm that guides the eye around the picture.

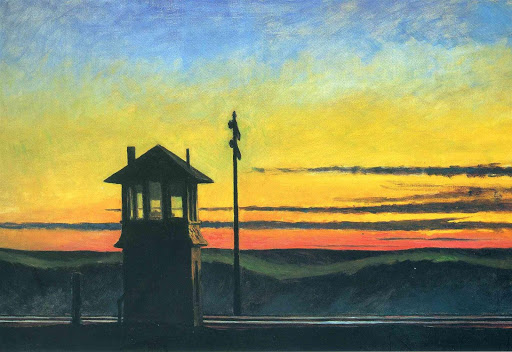

A contemporary of Sheeler, Edward Hopper’s series of paintings depicting the railroad landscape are a touchstone for my earlier images at Storm King and Iona Island. Hopper, in contrast to the precisionists, was less overtly interested in the shapes and lines of American industry. His was a judicious observation of how light communicates mood in a fleeting context, and this demanded a technique less geometrically realistic than the precisionists. His later work, such as “Road and Trees” (1962), abandoned figures and suggested movement through an empty landscape.

The way these painters applied color to the ostensibly drab and everyday elevated their subjects beyond the ordinary into the realm of what I’ve come to label documentary and poetic. I adhered to an exploration of the railroad landscape using color film because I enjoyed the challenge of ‘searching’ for color in these places, and while I wanted to work to have a documentary aspect, I felt using color would free me from the constraints of a full-on documentary mode.

After my research, I began to connect with those who struggled to capture the same animistic quality of the landscape as I was. But most importantly I saw in their work ingredients to help move forward in my photography. If you haven’t noticed yet, the tracks are an overarching visual motif and I will look into how they operate within a picture.

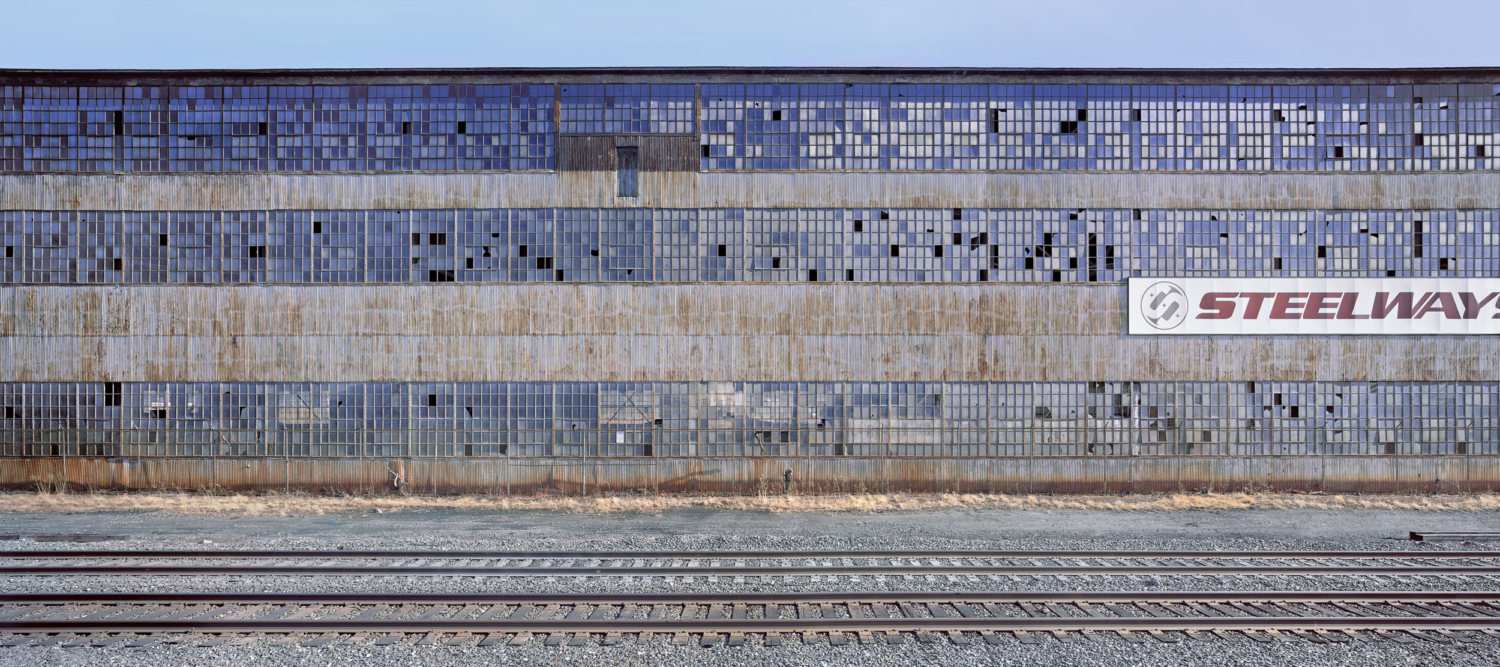

Gesture of Line

Gesture is defined as the shape of the rails in each picture and develop from three main types of perspective. Zero point horizontal perspective is associated with the views of the tracks running across the frome. It is a view I became drawn to early on when there weren’t any trains present, such as Storm King, New York, 2003. I felt an urge to capture these scenes — and having an interest in architecture, the similarity to an architect’s elevation drawings in some of these views was sobering (such as Steelways Shipyard, Newburgh, NY). Two other perspectives in my work are the more catchy one point and two point perspectives, such as the tracks disappearing into the horizon. My work started to take on certain conventions formed out of these three styles of perspective. Patterns emerged with how the tracks fit into each landscape — be it natural, urban, or industrial.

In the above diptych, we see two photographic modes underpinning the series. The first is what I’ve come to call cross-illustration and the second a counterpoint between the documentary and poetic. Cross-illustration is illuminating as it recapitulates similar elements across a two separate pictures. If you will pardon me I am often guilty of comparing photography to music since I feel their share similarities in structure. Cross illustration is akin to the recurrence of a melody within a musical composition (maybe a symphony) — what it does for the listener, or in this case the viewer, is to restate an idea in a different context. While the context may be different, the similarity of line or shape within the image recalls its previous iteration and is therefore familiar to the viewer.

In establishing a documentary and poetic mode, we see two images that are captured in different light and which perhaps embody contrasting mood – but I will let the images do to what they will to you and not direct too much. To briefly define my terms, the documentary is that which reveals particulars of a certain place at a certain time – in other words, a historical quality. The poetic indicates a heightened mood and directs how the photograph portrays its subject – for instance, the attribution of light and weather. When developing projects or bodies of work, I relate each picture through recurring motifs and the aforementioned idea of cross-illustration. The documentary/poetic mode runs across these projects at various intervals. Juxtaposing the harmonious and dissonant at varied intervals can only lead to a better understanding of how these objects function visually within the railroad landscape. Sorry I’ve devolved into using musical jargon again, but really musical terms are very useful when speaking about visual art… don’t you think?

Photo as Document

I wish to return to my earlier work for a moment. Coming from a background in political science, I am drawn towards subjects which describe a layered history. Even from my earliest railroad images, I was interested in the context the railroad, particularly structural elements — both urban and natural. Indeed, despite the interpretative power of railroad paintings, it is photography’s ability to act as a document, as well as an expressive object, which interests me.

As I corresponded with Jeff Brouws about my project, the book Metropolitan Corridor came up, written by John Stilgoe, this book deconstructs the American Railroad and the variety of environments it connects — from the city, countryside, to the remotest of districts. Although my project was well underway at that point, this text became a touchstone for me. As photographers and artists, I feel it important to understand the context with which we are working. Looking outside our specialty frees us and helps reinforce the meaning in our work. I have been working with the New York Transit Museum in developing a teen education program — and during our first round of workshops in the Fall, Metropolitan Corridor proved a great text to give the students a background on the American railroad.

“Metropolitan Corridor designates the portion of the American built environment that evolved along railroad rights-of-way in the years between 1880 and 1935. No traditional spatial term, not urban, suburban, or rural, not cityscape, or landscape, adequately identifies the space that perplexed so many turn of the century observers. Reaching from the very hearts of great cities across industrial zones, suburbs, small towns, and into mountain wilderness, the metropolitan corridor objectified in its unprecedented arrangement of space and structure a wholly new lifestyle. Along it flowed the forces of modernization, announcing the character of the twentieth century, and abutting it sprouted new clusters of building. Its peculiar juxtaposition of elements attracted the scrutiny of photographers and advertising illustrators; its romance inveigled poets and novelists; its energy challenge architects, landscape architects, and urban designers. Always it resisted definition in traditional terminology. And suddenly, in the years of the Great Depression, in the ascendancy of the automobile, it vanished from the national attention. Yet the corridor remains, although now often screened by sumac and other jungle like trees and avoided by highways, still snaking from one well-known, often-studied sort of space to another.”

-John Stilgoe

Technique

I began working with large format view cameras at the urging of my mentor in High School. Because of the camera’s slower process, I began doing much more of the composition and camera placement decisions in “the mind’s eye” as Ansel Adams would say, prior to photographing. This influenced my work. The Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, whose exhibition Manufactured Landscapes introduced me to the industrial sublime in photography, coined the phrase “contemplated moment” to describe the slower process with his large format cameras. This is in contrast to Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment.” I think this is a great way to look at working with large format. Looking at the railroad landscapes we see scenes which are suited to the use of large format. These include long views with fine detail and architectural views where the camera’s movements allow the correction of perspective.

I will now turn to a discussion of pictures.

END