Peter Watkins

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

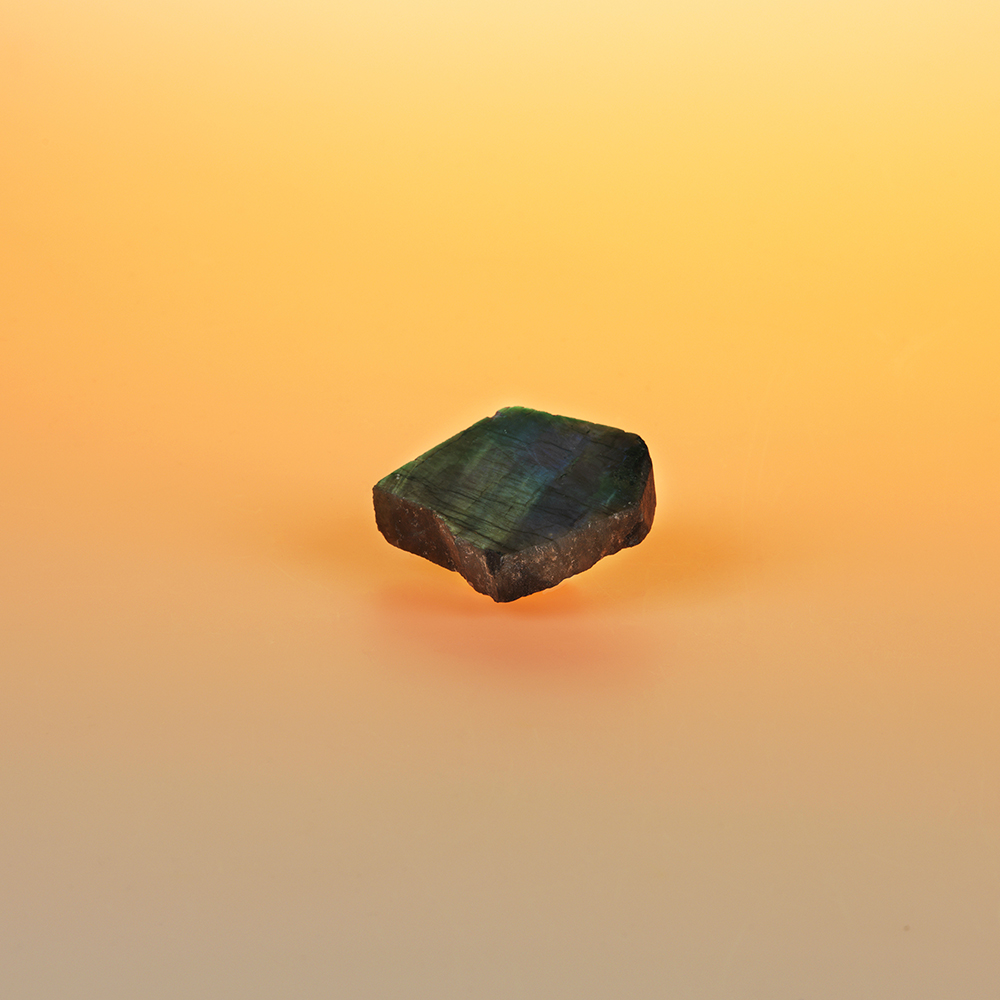

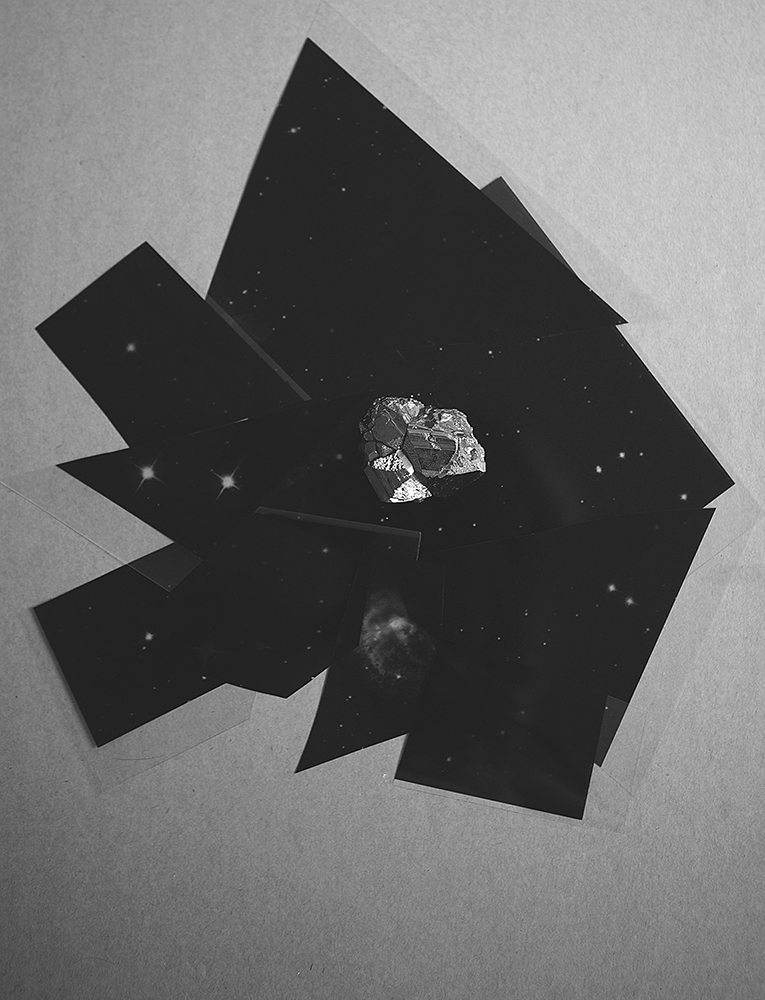

Alexandra Lethbridge - The Meteroite Hunter

Jun 03, 2015

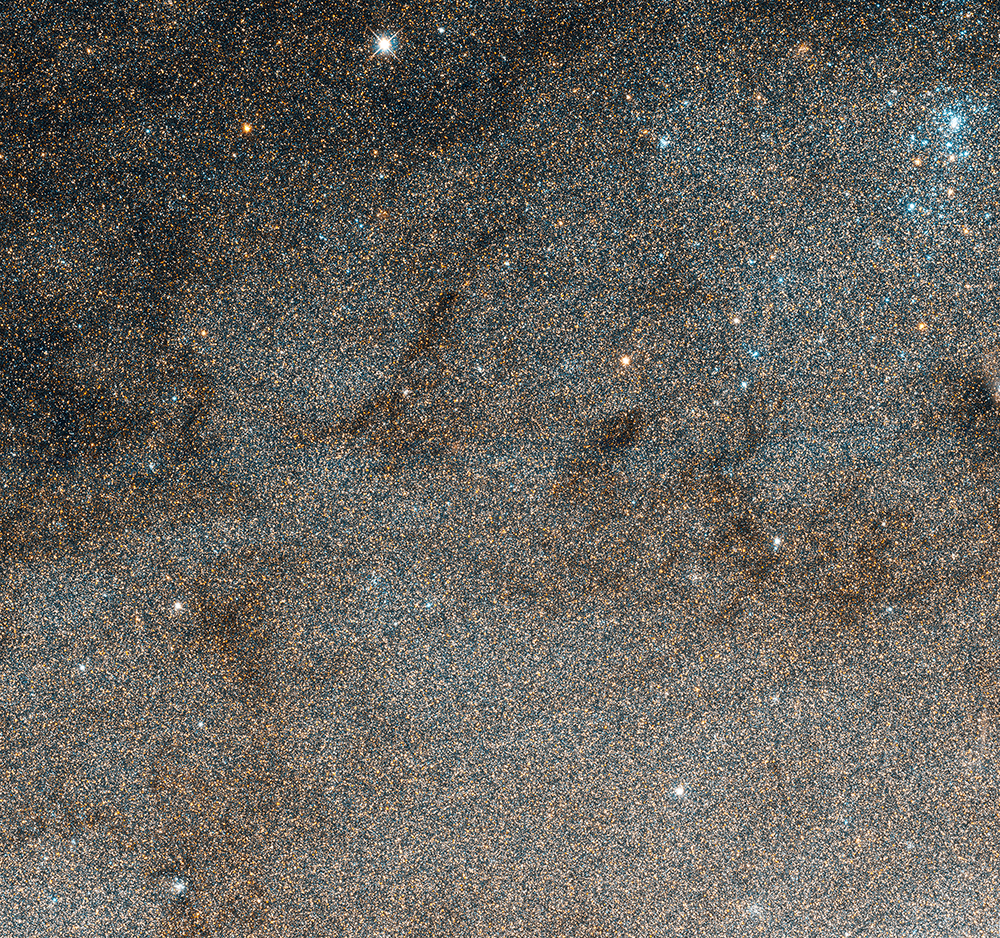

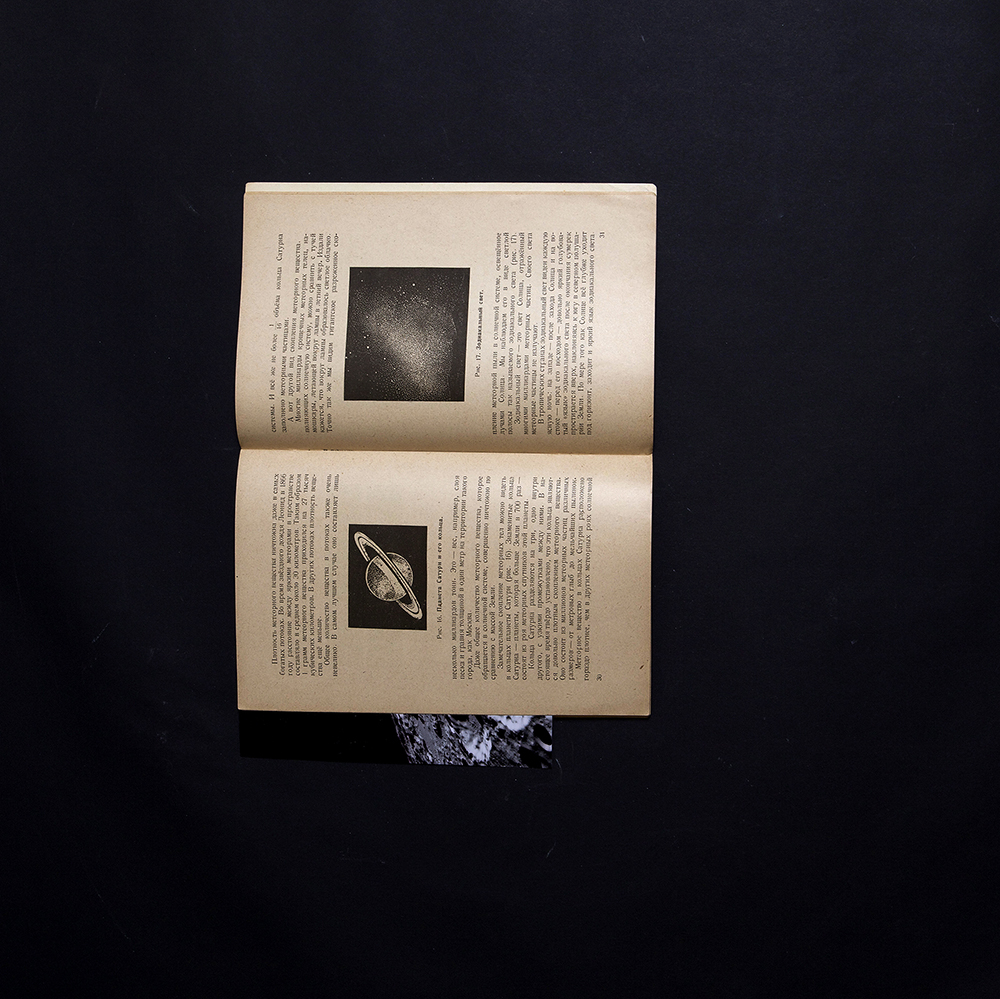

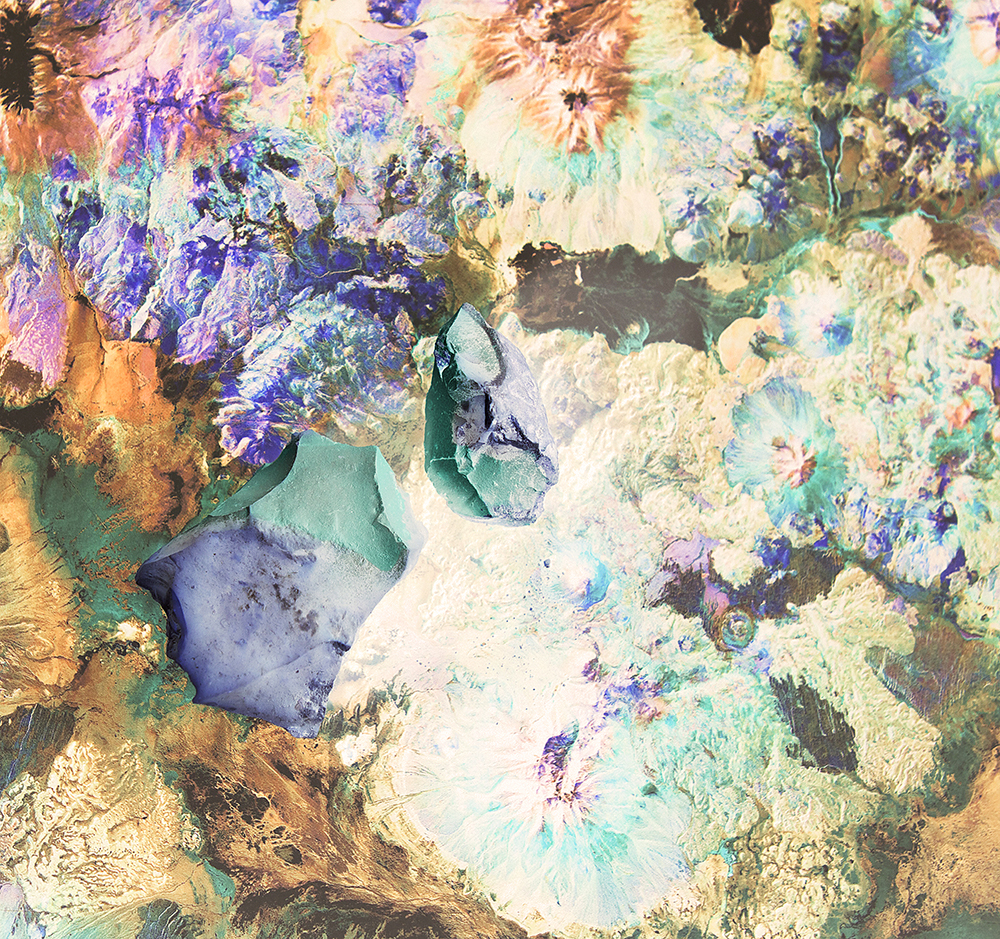

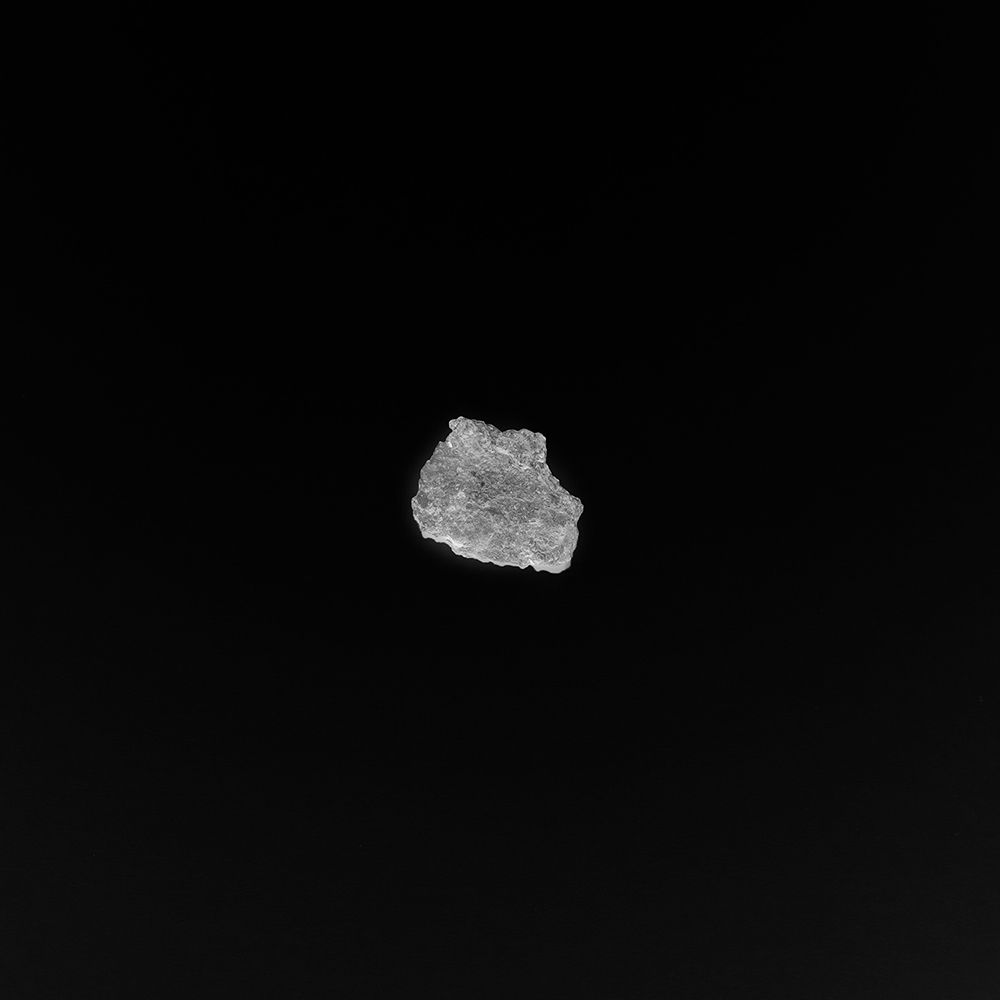

The Meteorite Hunter is an archive of a search for meteorites and the places they come from. A Meteorite Hunter is someone who commits to the art of finding space rocks in a focused pursuit. Their job entails searching for a glimpse of a translunary guest, a clue to something that tells us more about who we are and where we come from. Using the notion of the Meteorite as a metaphor for the fantastical hidden in the everyday, the body of work is a document of a hunt to locate the ethereal and sublime in the mundane and banal. The resulting archive acts as evidence to this search, documenting the accumulation of artifacts overlooked in search of the exotic. Using these ideas, the work aims to challenge our preconceptions of our surroundings and question the parallels between our own world and our imaginations. All images in the series vary in size and are printed on a combination of tracing paper and photographic paper. The work includes a selection of found images and objects.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Der Greif #8«

Jury Service Inspiration

Jun 09, 2015 - Alexandra Lethbridge

href="https://dergreif-online.de/www/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/11.jpg"> For my last post I thought I would end with some thoughts about my next body of work. I’m carrying on with my ideas around perceptions and narratives, trying a new route to explore these.

A few months ago, I was called to do Jury Service, which I have to say, filled me with dread. I’m not very good with blood and as a result, steer well clear of horror films and the likes. I was convinced I was going to be assigned to a gory, drawn out murder case and would have the spend the rest of my days in counselling to recover from it. The reality when looking back on this is fairly amusing, but needless to say, at the time, my imagination got away from me and I was sure this was my fate.

Jury service as a whole, is fairly tedious. Ample amounts of hanging around, tea breaks and Jeremy Kyle on repeat. I was actually assigned to a case, to which I had mixed feelings - I wanted out of the waiting room but I felt anxious about what the case might entail.

Luckily for me, I had a fairly tame case, a bust up on a night out, fairly standard stuff and nothing you wouldn’t see for yourself if you happened to find yourself in the wrong place at the end of the night. The interesting part came in the CCTV footage. The positioning of the fight in relation to the camera meant that the head of a lamppost was obstructing the view precisely at the point at which the fight got serious. What we as a Jury, were there to decide, was who was to blame.

We were presented with some pretty solid evidence. One man missing a tooth, another man with a cut in his hand which included a large fragment of tooth - not his own. I was pretty sure at this point that we could wrap it up. But it wasn’t that simple. As we couldn’t see this happen, we had to conclude, or be persuaded by the prosecution, that this DID happen. There were arguments presented of self defence. Perhaps the tooth lodged in the man’s hand was there because he hit his opponent in the mouth, but maybe he did that because he was hit first?

Once all the facts were presented, we gathered to deliberate. Having heard from all the witnesses on their accounts of the night’s events, it was still fairly clear that it hadn’t been in self defence. But yet we couldn’t be sure. We watched that CCTV footage again and again, to see if there was something, anything that could help clarify what had gone on behind that lamppost. But there was nothing. And because of that we had to conclude that he wasn’t guilty. Or he was guilty but we couldn’t prove it and the defence hadn’t done enough to prove anything either. So he was let off on the basis that we could not be sure, beyond reasonable doubt that he had committed the assault.

The process was a real eyeopener. The outcome was fairly unsatisfying and although I could see the logic, it didn’t seem to me to be completely truthful. At the time, I was starting work on another project, but I became obsessed with this notion of what we think vs what we know in particular relation to the justice system. In the same way that I used Meteorites and Space to discuss ideas, here suddenly was another way to interpret those very same ideas but in a completely different format. This new work is still in it’s early stages currently.

For my last post I thought I would end with some thoughts about my next body of work. I’m carrying on with my ideas around perceptions and narratives, trying a new route to explore these.

A few months ago, I was called to do Jury Service, which I have to say, filled me with dread. I’m not very good with blood and as a result, steer well clear of horror films and the likes. I was convinced I was going to be assigned to a gory, drawn out murder case and would have the spend the rest of my days in counselling to recover from it. The reality when looking back on this is fairly amusing, but needless to say, at the time, my imagination got away from me and I was sure this was my fate.

Jury service as a whole, is fairly tedious. Ample amounts of hanging around, tea breaks and Jeremy Kyle on repeat. I was actually assigned to a case, to which I had mixed feelings - I wanted out of the waiting room but I felt anxious about what the case might entail.

Luckily for me, I had a fairly tame case, a bust up on a night out, fairly standard stuff and nothing you wouldn’t see for yourself if you happened to find yourself in the wrong place at the end of the night. The interesting part came in the CCTV footage. The positioning of the fight in relation to the camera meant that the head of a lamppost was obstructing the view precisely at the point at which the fight got serious. What we as a Jury, were there to decide, was who was to blame.

We were presented with some pretty solid evidence. One man missing a tooth, another man with a cut in his hand which included a large fragment of tooth - not his own. I was pretty sure at this point that we could wrap it up. But it wasn’t that simple. As we couldn’t see this happen, we had to conclude, or be persuaded by the prosecution, that this DID happen. There were arguments presented of self defence. Perhaps the tooth lodged in the man’s hand was there because he hit his opponent in the mouth, but maybe he did that because he was hit first?

Once all the facts were presented, we gathered to deliberate. Having heard from all the witnesses on their accounts of the night’s events, it was still fairly clear that it hadn’t been in self defence. But yet we couldn’t be sure. We watched that CCTV footage again and again, to see if there was something, anything that could help clarify what had gone on behind that lamppost. But there was nothing. And because of that we had to conclude that he wasn’t guilty. Or he was guilty but we couldn’t prove it and the defence hadn’t done enough to prove anything either. So he was let off on the basis that we could not be sure, beyond reasonable doubt that he had committed the assault.

The process was a real eyeopener. The outcome was fairly unsatisfying and although I could see the logic, it didn’t seem to me to be completely truthful. At the time, I was starting work on another project, but I became obsessed with this notion of what we think vs what we know in particular relation to the justice system. In the same way that I used Meteorites and Space to discuss ideas, here suddenly was another way to interpret those very same ideas but in a completely different format. This new work is still in it’s early stages currently.

The Weather Project – Olafur Eliasson

Jun 08, 2015 - Alexandra Lethbridge

In looking at the ways that we can be taken to different places and how our perceptions can shift, an exhibition that had a real influence on me, is Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project. I went to see this exhibition when it was at the Tate Modern in 2003 and was completely overwhelmed by the reaction I had to it. Viewers of the exhibition would come and lie down under the ‘sun’, a habitual reaction to seeing the presence of the sun. There was absolutely no heat generated by this installation. The representation of the sun came in the form of a visual representation of the sun through mirrors, and lighting to mimic the warmth radiating from it. There were also humidifiers that would pump a mixture a sugar and water into the air to create a mist. The illusion of the sun was created by a half circle of light reflecting off of different jagged mirrors placed on the ceiling. This means that the illusion of the sun is fractionally offset which makes it more believable, almost as if it was shimmering. By placing mirrors on the ceiling, sun bathers were shown a reflection of themselves and viewers would be seen to be waving their hands and legs in order to find themselves in the mass of people. All this helped to add to the sense of scale created by the sun and as a viewer you couldn’t help but feel you were dwarfed by this radiating mirage. It actually had a real calming effect, much like you would have on the beach and it worked to make you think you had connected with the energy of the sun in some way. This show stuck me with for its ability to helps me to translate an experience in a certain way. I began to understand what it takes to represent a notion, or an element, without having the substance of the element present. Oddly, having recently visited Photo London on the opening night, I can’t imagine the turbine hall transforming so radically as it did when that show was open. It was a real indication to me at an early age of how immersive art could be.

Blindness and Memory

Jun 07, 2015 - Alexandra Lethbridge

rrying on with my previous posts in thinking about seeing differently and changing perspectives, a talk that has never failed to inspire me is Professor John Hull on Blindness and Memory. Hull lost his sight in 1980 and has now spent the same amount of time without sight as he spent sighted. He talks about how his experience lead him to understand that vision is directly related to visual memory, and that loss of the former leads to loss of the latter. As his vision finally left he entered into a process of relearning and remapping his surroundings to see acoustically. As his vision finally left after a slow recline into blindness, Hull said:

‘I had not been a blind person; I had been a sighted person who couldn’t see. I began to enter into deep blindness. What I mean by that is that visual memory began to disappear.’

He begins to relate the disappearance of his visual memory to an imagined visit to the National Portrait Gallery in which during each visit, different portraits disappear and are left blank - no longer visible. The comparison of the memory to a framed object, much like the photograph, shows how Hull was relating his visual memory to ‘remembered’ portraits that speak more to traces of memory rather than real experiences. He reiterates this point when discussing the memory of his wife.‘I found it hard to remember (his wife’s face) but there were certain photographs I could remember.’

When confronted with loss of memory, it’s interesting to think that our recall for photos stays longer than our memory of the real person or event. He ends his talk by discussing how his tactile memory has taken over his visual memory. If you have some spare time, I highly recommend watching the talk. It’s connections to how we process images in relation to our memories is a real eye opener. [vimeo video_id="61088287" width="1000" height="563“]The Overview Effect

Jun 06, 2015 - Alexandra Lethbridge

href="https://dergreif-online.de/www/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/AlexandraLethbridge04.jpg"> My work in the broadest sense explores ideas of reality vs fiction. I’m interested in how our perceptions react to those notions and the role our imaginations play in navigating between the two. My most recent body of work, The Meteorite Hunter, was a way for me to explore perception by presenting a collection of artefacts and concealing the source of their origin. The images that make up the project consist of found images sourced from places such as EBay, as well as images sourced from NASA’s online archive.

During my research into NASA, I came across a scientific phenomenon called The Overview Effect. I wanted to share the resulting essay I wrote as part of that research.

The Overview Effect is the scientific phenomenon experienced when astronauts are faced with the sight of Earth from Space. In the act of looking back at the orbiting Earth they experience an overwhelming sense of the Earth as a collective being, a feeling that stays with them once they have returned home. The notion became so commonly reported amongst returning astronauts that an institute was formed dedicated to its study. The fascination with this phenomenon is the value of looking at something so familiar with a renewed sense of importance and perspective. In the space expeditions astronauts undergo, the focus is always on discovering the new, unfound and alien but many report the sensation of looking back upon what we experience every day, as the most eye opening of all discoveries.

So often the familiar is overlooked in favour of the exotic as we crave to see and experience things that are strange and different to us. Sometimes the perception of something extraordinary or unusual lies within our control and the search for the otherworldly becomes an obsession where the reward is always out of reach.

The epitome of that is The Meteorite Hunter. This hunter is someone who commits to the art of finding space rocks in a focused pursuit more akin to a necessity than a desire. Their job entails searching for a glimpse of a translunary guest, a clue to something that tells us more about who we are and where we come from. The Meteorite itself becomes the reward, driving hunters through our landscapes to find clues of its whereabouts. The Meteorite, in her modest way, hides within our surroundings in layers of sand and dirt, her exotic homeland concealed in her camouflage.

As the hunter travels, so too does the Meteorite; its flight can be broken down into segments. In orbiting through space the rock exists as a Meteoroid. Once in the Earth’s gravitational pull it becomes a Meteor and if it manages to impact with Earth and survive it becomes a Meteorite. The journey becomes a signifier. Space; pointing to the ethereal and celestial and Earth; to the concrete and factual. The act of the extraterrestrial Meteor landing on Earth creates a realm where these two things interact in a way that is most unusual and unexpected.

The Meteorite Hunter himself becomes the guide between these two realms, anticipating and calculating the arrival of any of these specimens. The job of a Meteorite Hunter is one of patience, understanding and skill. The constant, relentless searching expresses a need to understand more than we know and more than we have. The hunt sees them sift and wade through our earthly rubble, constantly casting aside the fantastic objects that exist all around us in favour of the celestial and otherworldly. Soon the artefacts that are collected along the way begin to cluster and multiply until there exists a vast archive of forms acting as evidence. When we view the archive as a collection, as an overview of the hunt undertaken by the Meteorite Hunter, we lose the separations between what is ‘mundane’ and ‘sublime’. In questioning the origin of any of these objects we un-know what is familiar and therefore overlooked.

When we consider the relationship between space and earth and engage with the process of The Meteorite Hunter, we are given the opportunity to connect these two realms and it is this resulting synergy that breaks down the separation between this world and the universe. In this space we are invited to consider the two as being connected and as one. In considering how viewing the whole can teach us more than the sum of the parts, the value of the Overview Effect becomes apparent. Being able to consider and appreciate our surroundings with renewed appreciation frees us from the search and welcomes us to contemplate the place we find ourselves in here and now.

My work in the broadest sense explores ideas of reality vs fiction. I’m interested in how our perceptions react to those notions and the role our imaginations play in navigating between the two. My most recent body of work, The Meteorite Hunter, was a way for me to explore perception by presenting a collection of artefacts and concealing the source of their origin. The images that make up the project consist of found images sourced from places such as EBay, as well as images sourced from NASA’s online archive.

During my research into NASA, I came across a scientific phenomenon called The Overview Effect. I wanted to share the resulting essay I wrote as part of that research.

The Overview Effect is the scientific phenomenon experienced when astronauts are faced with the sight of Earth from Space. In the act of looking back at the orbiting Earth they experience an overwhelming sense of the Earth as a collective being, a feeling that stays with them once they have returned home. The notion became so commonly reported amongst returning astronauts that an institute was formed dedicated to its study. The fascination with this phenomenon is the value of looking at something so familiar with a renewed sense of importance and perspective. In the space expeditions astronauts undergo, the focus is always on discovering the new, unfound and alien but many report the sensation of looking back upon what we experience every day, as the most eye opening of all discoveries.

So often the familiar is overlooked in favour of the exotic as we crave to see and experience things that are strange and different to us. Sometimes the perception of something extraordinary or unusual lies within our control and the search for the otherworldly becomes an obsession where the reward is always out of reach.

The epitome of that is The Meteorite Hunter. This hunter is someone who commits to the art of finding space rocks in a focused pursuit more akin to a necessity than a desire. Their job entails searching for a glimpse of a translunary guest, a clue to something that tells us more about who we are and where we come from. The Meteorite itself becomes the reward, driving hunters through our landscapes to find clues of its whereabouts. The Meteorite, in her modest way, hides within our surroundings in layers of sand and dirt, her exotic homeland concealed in her camouflage.

As the hunter travels, so too does the Meteorite; its flight can be broken down into segments. In orbiting through space the rock exists as a Meteoroid. Once in the Earth’s gravitational pull it becomes a Meteor and if it manages to impact with Earth and survive it becomes a Meteorite. The journey becomes a signifier. Space; pointing to the ethereal and celestial and Earth; to the concrete and factual. The act of the extraterrestrial Meteor landing on Earth creates a realm where these two things interact in a way that is most unusual and unexpected.

The Meteorite Hunter himself becomes the guide between these two realms, anticipating and calculating the arrival of any of these specimens. The job of a Meteorite Hunter is one of patience, understanding and skill. The constant, relentless searching expresses a need to understand more than we know and more than we have. The hunt sees them sift and wade through our earthly rubble, constantly casting aside the fantastic objects that exist all around us in favour of the celestial and otherworldly. Soon the artefacts that are collected along the way begin to cluster and multiply until there exists a vast archive of forms acting as evidence. When we view the archive as a collection, as an overview of the hunt undertaken by the Meteorite Hunter, we lose the separations between what is ‘mundane’ and ‘sublime’. In questioning the origin of any of these objects we un-know what is familiar and therefore overlooked.

When we consider the relationship between space and earth and engage with the process of The Meteorite Hunter, we are given the opportunity to connect these two realms and it is this resulting synergy that breaks down the separation between this world and the universe. In this space we are invited to consider the two as being connected and as one. In considering how viewing the whole can teach us more than the sum of the parts, the value of the Overview Effect becomes apparent. Being able to consider and appreciate our surroundings with renewed appreciation frees us from the search and welcomes us to contemplate the place we find ourselves in here and now.

Utopian Impulses in Practice

Jun 05, 2015 - Alexandra Lethbridge

I thought I would show some work by other photographers using interventions and experimental techniques to create imagery and expand on some of the ideas I touched on in the last post. The first photographer I’m going to look at is Charlie Rubin and his use of interventions in his project Strange Paradise. This series works by combining photos that he has manipulated with imagery that he hasn’t but seems to have some kind of a fantastical quality about them. It is by playing with the juxtaposition of these two different kinds of images and what is real or fictional, that you begin to engage with this place as possibly existing. It’s in that moment of uncertainty about whether this is real of not that acts in the interpretative space of the Utopian. He has also managed to create a place that is close enough to reality to confuse us but still show evidence of a fictional space. In Thomas More’s writings on Utopia, he talks about how the visibility in the construction and process of the Utopian must be evident for it to be Utopian at all. Should it be too convincing, we might believe it was real and then it couldn’t be imaginary and in turn hold the ideals of Utopia. This point is really important in understanding Utopia within Photography. Another good example of this is Noemie Goudal. She creates constructed spaces leading to make believe worlds where she examines the idea of the photograph as evidence. Her work is based heavily in the construction of this other world. Taking images and reconstructing them into other spaces, she creates a third plane where these two layers exist together. The on site collages that she makes are not pretending to be anything other than what they are. The construction of the interior images are obviously just that – constructions and this visibility is what tells us this is an illusion and allows us to enter it. Andre Bazin in his writings on the Ontology of the Photographic Image, describes the Photograph using the word Hallucinatory. It’s a very interesting use of the word - it opens up our understanding of how we interpret the photograph, particularly in relation to it being truthful. The two photographers I have shown both translate this notion in different ways but ultimately achieve the same results in leading us to an illusionary world through the one we know. Moving forward, I began to think about the reasons for using interventions. Following an email interview I conducted with Julia Cockburn during my Masters – another artist working with found imagery and interventions to create images, I asked her what drives her to make the kind of work she does and I found her response very interesting. “My interventions of cutting or sewing or adding new objects are not supposed to be illustrative. More, they are supposed to interrupt the viewer ‘knowing’ the image (the images I work on are archetypal, recognizable in the collective consciousness), and therefore hopefully able to ask of the piece and perhaps themselves, empathetic questions about what it is to be human.” My discussion with Julie showed me the advantage in disrupting the image is the ability to be able to say or translate something that may speak to a wider context. In the history of collage, the reason for combining 2 or more conflicting elements within the same plane is to be able to make a new form of thought arise. In the rupturing of the imagery, you are able to access an interpretative space outside the realm of traditional, representational photography and within this rupture, you are able to talk about concepts and ideas outside of our everyday experience. These ideas form the basis of my interest in Photography and the core themes that run through my work, in particular my last project, The Meteorite Hunter. For more of Charlie Rubin's work click here. For more of Noemie Goudal's work click here.

Utopian Impulses

Jun 04, 2015 - Alexandra Lethbridge

href="https://dergreif-online.de/www/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/AlexandraLethbridge02.jpg"> For my blog posts, I thought I’d do a series explaining my interests in photography and make a structure by which to discuss my practice and the ideas behind it.

My work plays between traditional and more experimental methods of image making so for this post I thought I’d discuss some of the theories that have inspired it.

My premise for understanding photography is to consider it as a portal. Portals can be thought of as a gateway or link to another place. Science Fiction has long been using portals; or wormholes as locations to travel though time and space without having to travel geographically to get to the destination. The idea of entering a portal is much like entering a photograph and it reminds me of photography’s ability to transcend the photographic print.

I started to think about what it was the portal was pointing to. Within my own work, what in particular was I looking for? What place was I linking to?

My research led me to ideas of Utopia. Thomas More coined the term in 1516 and it is defined as an ideal and perfect state. For the purposes of this post, I am using the idea of Utopia as a representational structure and choosing not to focus on the wider political and social connotations.

Frederic Jameson in his book Archeologies of the Future, talks about a ‘Utopian Impulse’, which is the need to search for Utopian aspects within our everyday. The definition of Utopian can change from person to person and relates to exactly what they are looking for. The term once translated literally means ‘no land’.

I’m interested in this idea as it sums up quite nicely, my own working relationship to photography and the things I look for when making work. This idea of a space between reality and representation begins to explain the kind of things I look for.

For my blog posts, I thought I’d do a series explaining my interests in photography and make a structure by which to discuss my practice and the ideas behind it.

My work plays between traditional and more experimental methods of image making so for this post I thought I’d discuss some of the theories that have inspired it.

My premise for understanding photography is to consider it as a portal. Portals can be thought of as a gateway or link to another place. Science Fiction has long been using portals; or wormholes as locations to travel though time and space without having to travel geographically to get to the destination. The idea of entering a portal is much like entering a photograph and it reminds me of photography’s ability to transcend the photographic print.

I started to think about what it was the portal was pointing to. Within my own work, what in particular was I looking for? What place was I linking to?

My research led me to ideas of Utopia. Thomas More coined the term in 1516 and it is defined as an ideal and perfect state. For the purposes of this post, I am using the idea of Utopia as a representational structure and choosing not to focus on the wider political and social connotations.

Frederic Jameson in his book Archeologies of the Future, talks about a ‘Utopian Impulse’, which is the need to search for Utopian aspects within our everyday. The definition of Utopian can change from person to person and relates to exactly what they are looking for. The term once translated literally means ‘no land’.

I’m interested in this idea as it sums up quite nicely, my own working relationship to photography and the things I look for when making work. This idea of a space between reality and representation begins to explain the kind of things I look for.

To try to clarify what I mean when I talk about this space between, I’ll share a fable by Jorge Luis Borges in his On Exactitude of Science. The fable is about a king who wanted to create a map of his empire. Maps were commissioned in all sizes, gradually getting larger and larger, until they created a map that was point for point the same size as the territory. The map became completely pointless and served no purpose.

The aspect of this story that stuck with me was the notion that an accurate copy of the ‘thing’ itself is completely useless. It’s in the differences between the map and the territory that it becomes useful, only gaining its power from selection and careful separation of reality and representation.

It’s this separation and the room for interpretation that then exists that I mean when speaking about the space between. This excerpt from an online article from the New Yorker really sums it up.

A map that is too exact becomes the thing it maps, endangering both Casey N. Cep, Allure of the Map, New Yorker Magazine, 2014

In the process of making work, generally I look to show something different and perhaps more interpretative than what I see. Photography offers me the choice to make something other than a copy. My interest has developed around the idea of photography as a method to see what we cannot see. Using the camera to reveal the world rather than document it. So in considering how photography might work specifically for my needs, I needed to work out what it is about the construction of a Utopia that is so appealing. In order for me to make sense of my work I needed to examine what I was looking for. Ernst Bloch in his book Principles of Hope talks about why we create ideas of Utopia. He states that we create Utopia because of the difference between our knowledge and our experience. By this theory the realization of Utopia exists in the gap between reality and our imagination. Another way of thinking about this might be, you may have heard of a country but never travelled there. So you may have built an idea of what this country looks like and what you might expect from it and that idea may be completely different to the country in which you live or have ever experienced. Frederic Jameson in his writings, says that if ideas of Utopia are born from our imagination then they are also limited by it. So to go back to my example, your ideas about this country, while they may seem more exotic than your current surroundings, the country itself may in fact be more elaborate than you could ever imagine, it being so far removed from your own experiences, that you have no point of reference to even contemplate what that might be like. It is in these exact limitations of what we know and therefore what we can imagine that leaves room for work that uses interventions within photography to represent Utopian ideas.