Louis Heilbronn

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

Ana Zibelnik - We are the ones turning (ongoing)

Mar 25, 2020

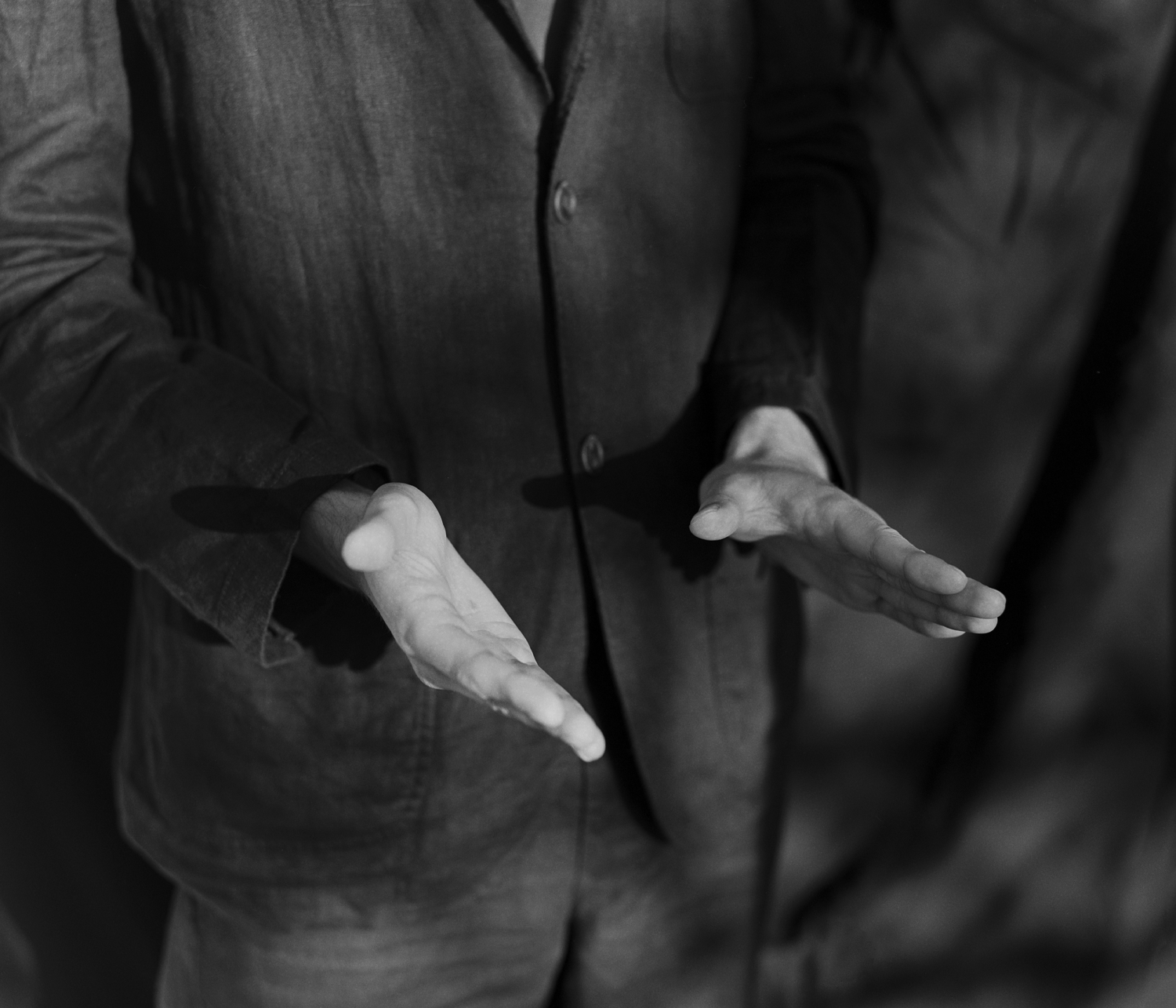

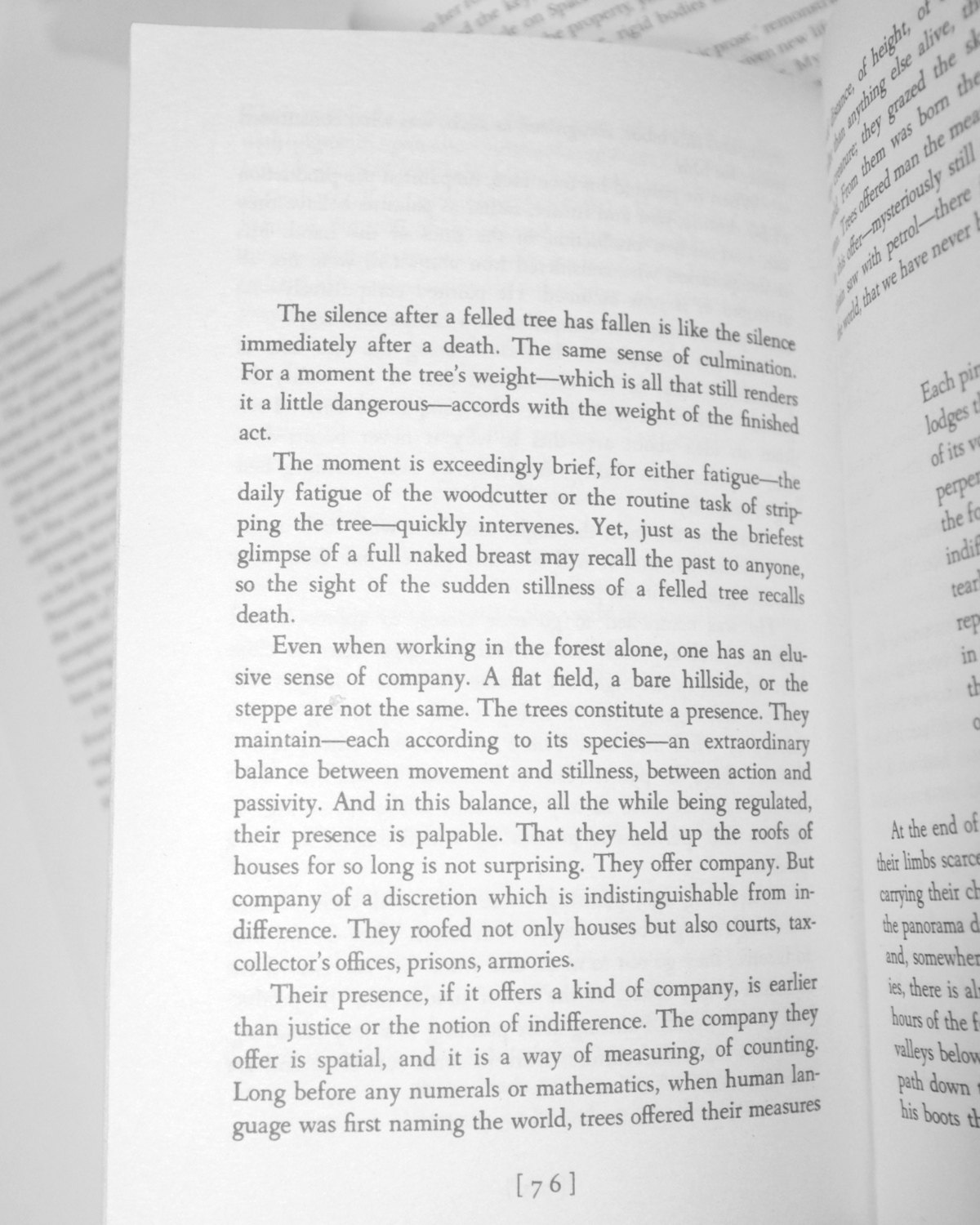

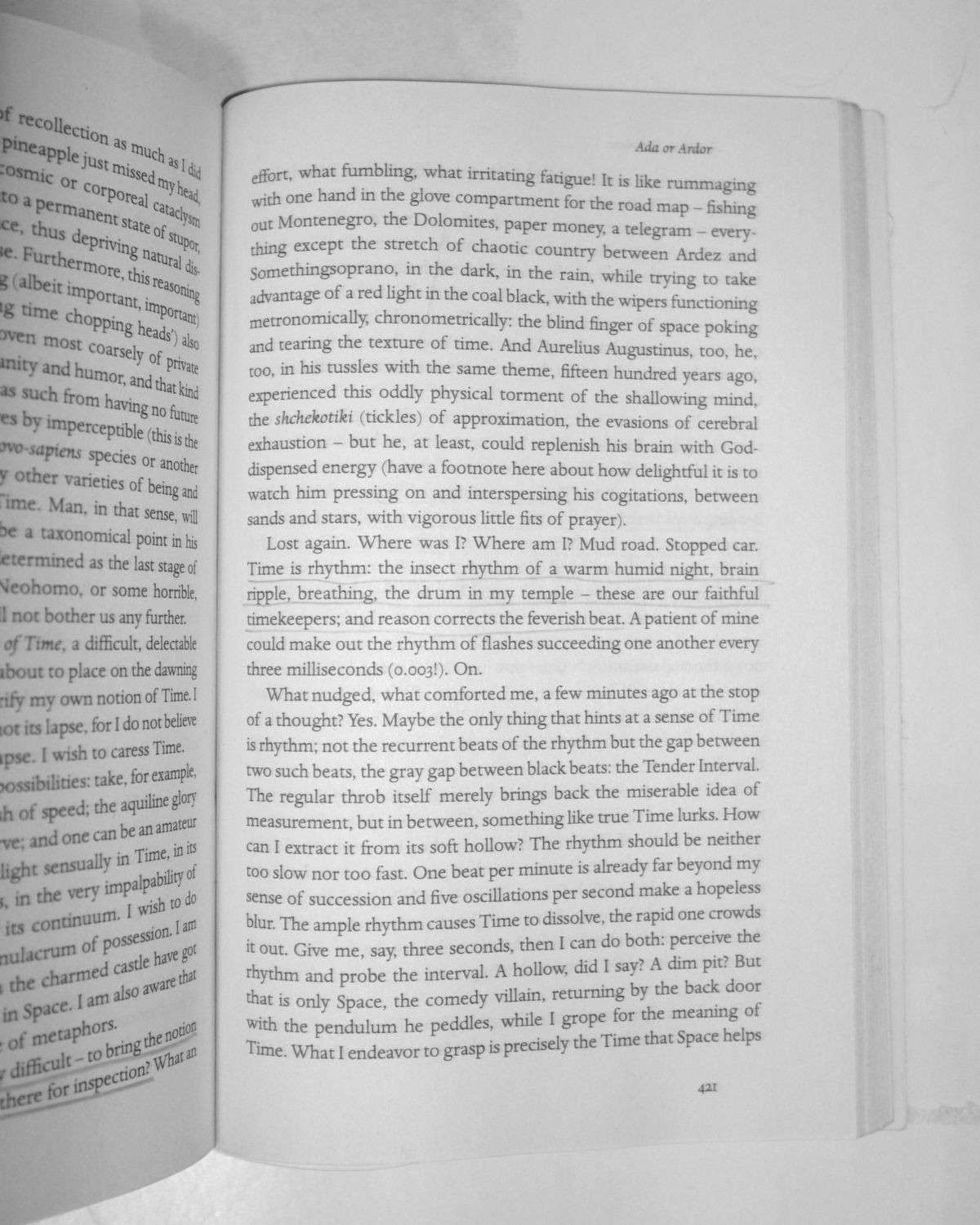

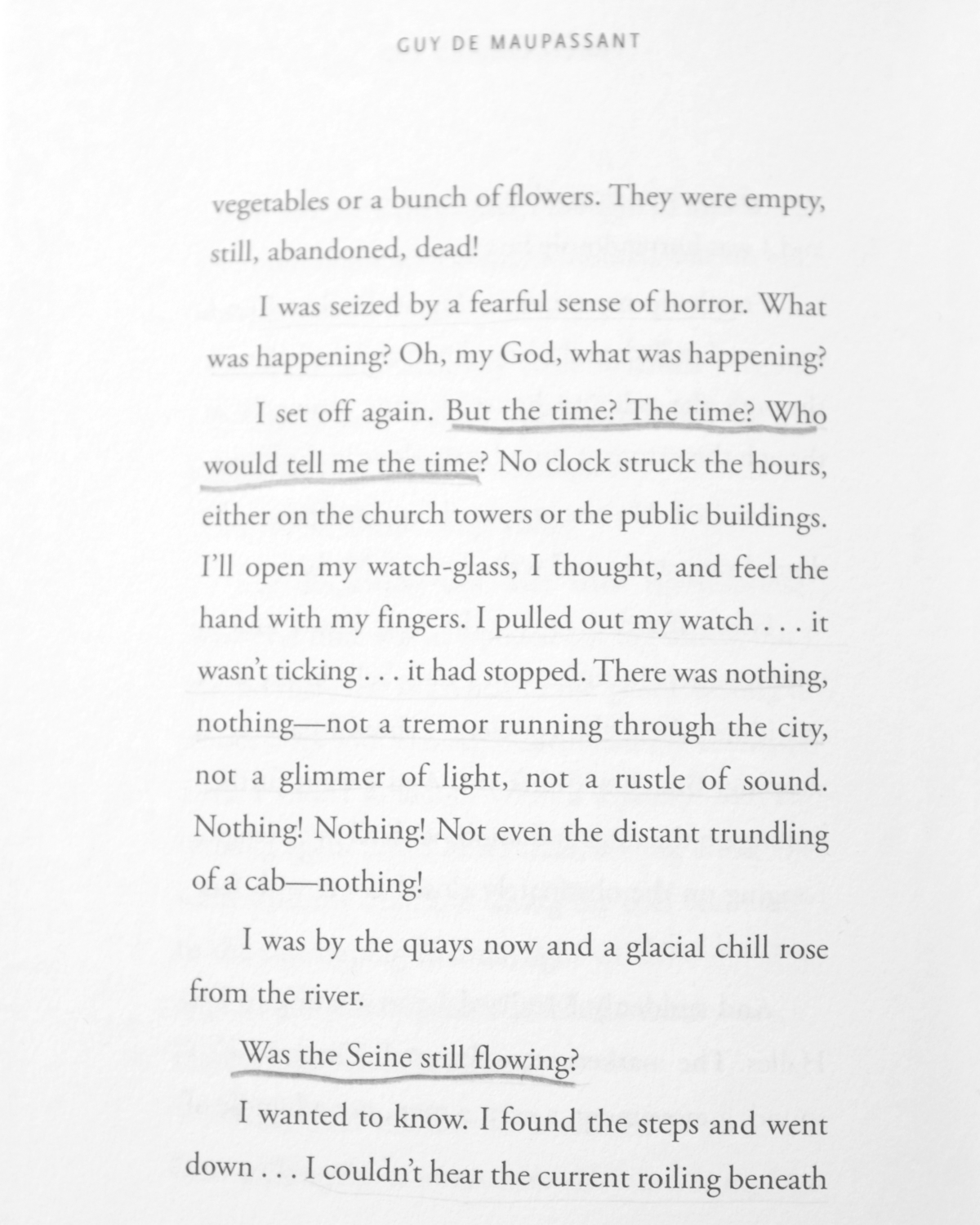

Mortals are those who experience death as death. In this sense, human beings are identified by an awareness of the fact that they are running out of time; an awareness which is reinforced and revisited simply by living. We are the ones turning explores how we grapple with the “possibility of impossibility” in everyday life – a topic that extends far beyond the fear of death and can deeply affect our perception of time. Zibelnik combines the prosaic with the uncanny, the sentimental with the insensible, thus contrasting the mechanical flow of time, symbolised by the clock, with our experience of it. The gesture of the turning hands, which sets the rhythm of the series as its Leitmotif, is derived from American Sign Language, where it indicates the notion of death.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Guest-Room Dominic Bell«

On Preventable Causes of Death

Mar 30, 2020 - Ana Zibelnik

An excerpt from On Preventable Causes of Death, an essay written by Jaka Gercar about longevity politics. All the photos are from our 2017 trip to Perdasdefogu – a small village in the Nuoro region of Sardinia:

“It would be difficult to say we had a dialogue; we had some kind of rapport, but it was hardly a propositional one. Obviously, the prevailing reason for this was the language. The other his age. But he held my hand firmly, as did his wife, and many other anziani. The physical contact established an acute sense of togetherness, difficult to achieve in talking. Then there were the beautiful toothless expressions of tenderness. Ana took photos of Armando from the moment we’ve entered. Nearing our departure she leaned closer towards me to say she went through three rolls of film, yet it seems like Armando will have the exact same facial grimace on all of them.

Albert Camus famously wrote that there comes a point in life after which a man is no longer responsible for his face. For a young person, the face is a tool, an instrument with which to express him- or herself, the face is a means to gesticulate and therefore take on an identity. Persona, the Greek word for mask, from which the English word person evidently derives, is not opposed to the “true essence” of any individual being; it is precisely the necessary and only way one can establish his or her identity. A supple face is multifarious. Contrary, an unyielding face well past its prime begins to resemble only itself. It is thus forthright and far more revealing. Even Bob Dylan, who as a young musician was convinced that he wakes up as one person and goes to bed as another, cannot help becoming Bob Dylan more and more with every day gone by. The hardships and the worries, the laughter and the cries, the labour and the leisure – nothing escapes the face. The wrinkles, crinkles and rumples deepen, the cheekbones become more visible, the tics get predictable. There seems to be a perfectly analogous phenomenon happening in the domain of the mind. Armando did not only wear his heart on his sleeve, but also his convictions on his collar. Some of the questions I posed to him were deliberately vague and simple; others not so much. For instance, we talked about the importation of large quantities of wheat from Russia and Ukraine. But to all of my questions, it seemed, his daughter already knew the answer to. Sometimes she replied even before interpreting the question loudly into her father’s ear, assertively adding: “You’ll see, he will say the same.” She was right every single time.”

Wuppertal

Mar 27, 2020 - Ana Zibelnik

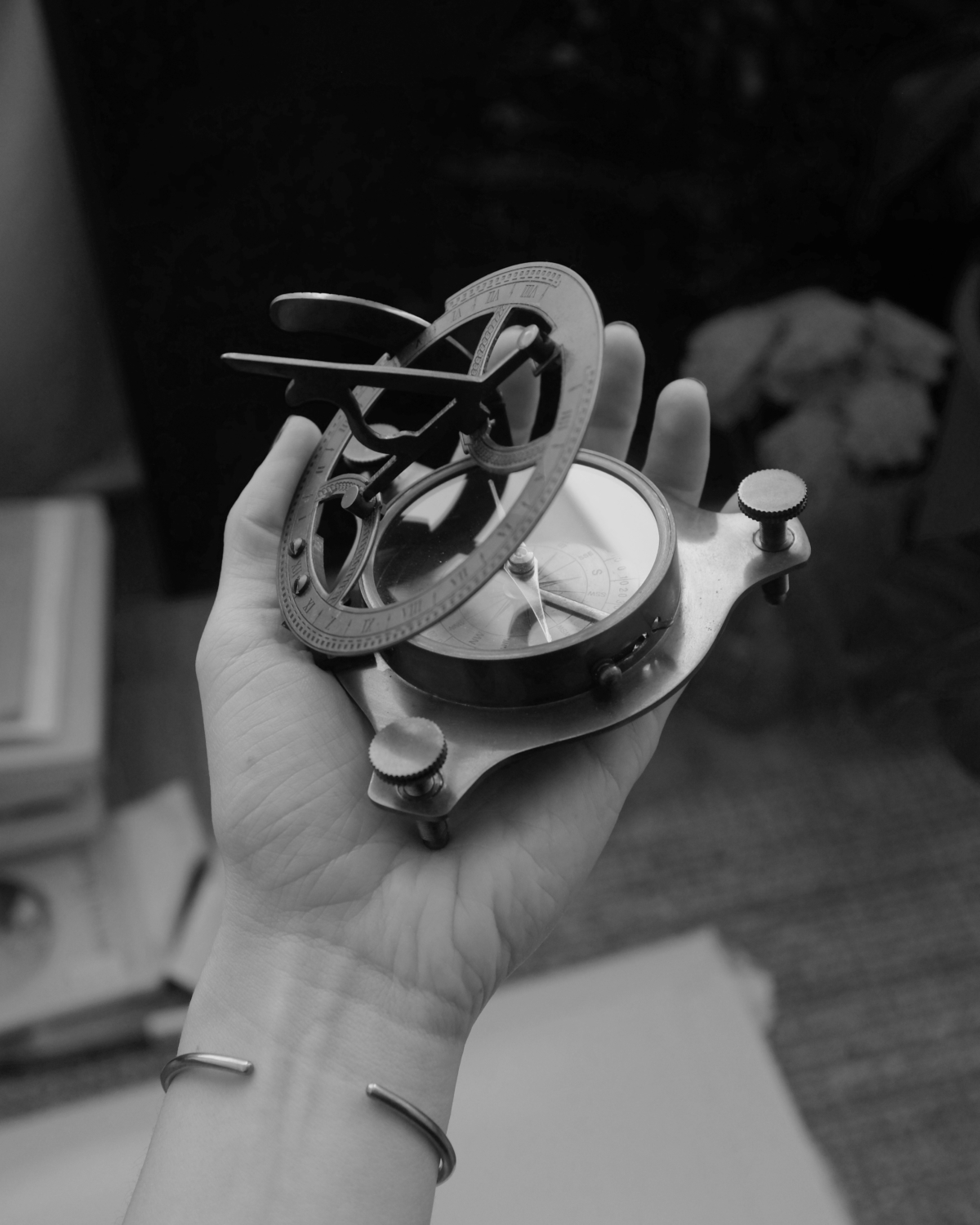

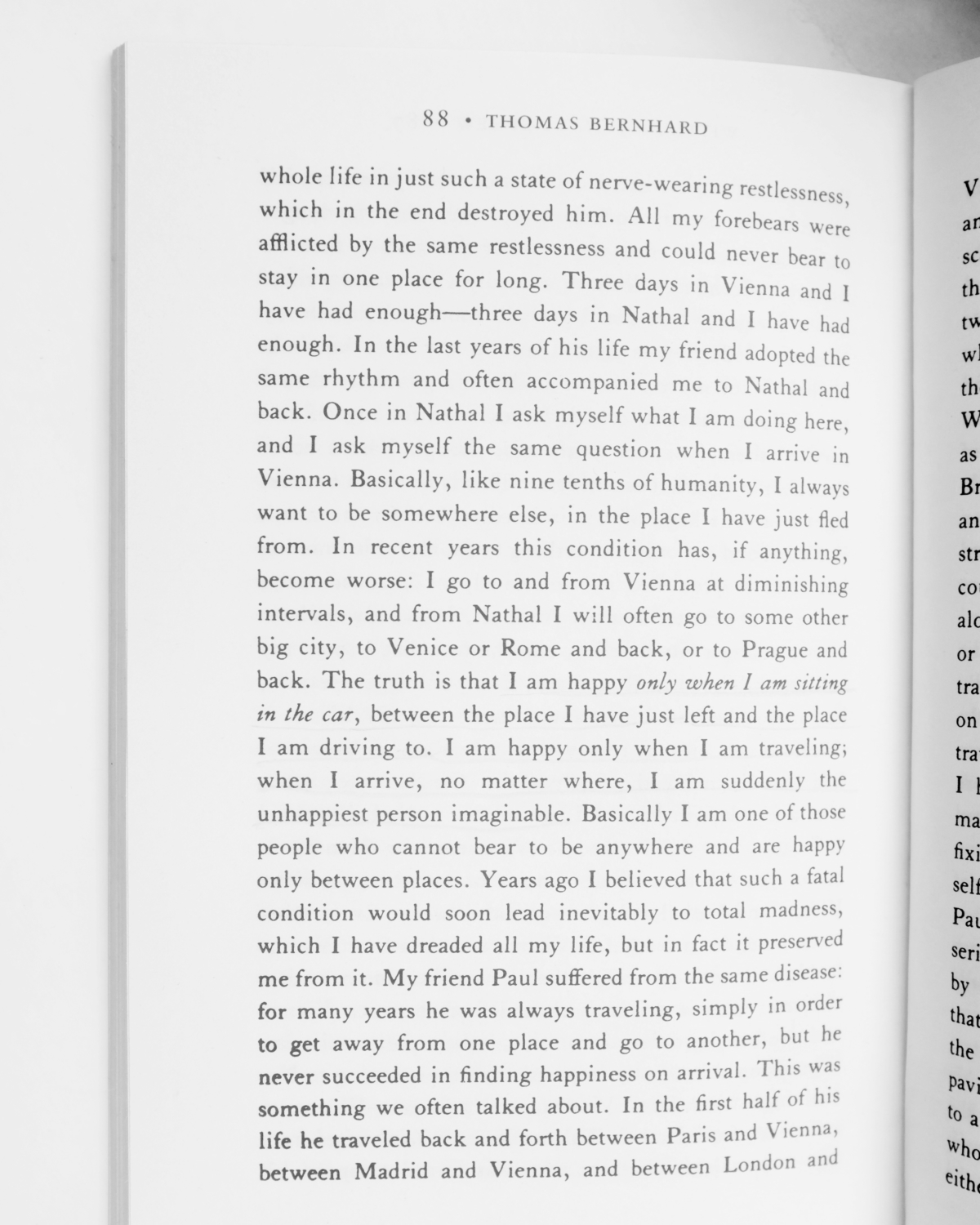

On my 24th birthday, I bought myself a compass. I found it in an antique store in Jordaan, Amsterdam, and it was terribly overpriced. At that time, it had been just over a year since we moved to the Netherlands and none of us liked it. What bothered me most was the country’s perfectly functioning and structured road and railway network. Commuting from A to B has never been faster and easier; a journey that would have taken a good hour at home could be over in just about 10 minutes. Even without the slightest knowledge of the language, it was extremely difficult to take the wrong train and get lost. We came here with an old Ford Mondeo, much too old to legally drive into the low-emission zones of contemporary cities, which I got from my parents in 2014 after gradually colonizing it with CDs, bottles, plastic cutlery, and blankets. I never thought about cars until I was without one, but family wheels hold a special place in my memory, especially in how they divide it into periods. The first one begins with a story told over and over again about how when I was just a few months old, I wouldn’t sleep unless somebody would drive me around on a bumpy road. It was a big blue Volkswagen Transporter from 1990, with the back seats removed in order to make space for musical instruments and two enormous speakers. On the sliding door, there was a sticker: music in motion. The kombi marked the nomadic years of my parents’ career as musicians and my endless journeys in the single remaining back seat. The Mondeo which I later adopted came after it and besides a switch of careers indicated a beginning of a more settled lifestyle: for me, the 12 years of primary and high school. On the day it arrived, I was so excited I accidentally boxed into a sandblasted wall and got myself a pretty painful hand injury. The third and last one was a white Jaguar that my mother bought immediately after moving to England. I always thought it looked cool, but it was again old, drank vast amounts of gas and kept breaking down. It was the car of exploring new territory, of cursing in various Balkan languages over driving on the left, and of slight sadness. There were countless occasions when it would pick me up or drive me to the airport which would make my mother’s eyes teary, and even more of being squeezed between my not so skinny grandparents on our longs trips to the coast while making vivid comparisons of every village or city we passed to those of Slovenian Styria. “Look, it is exactly like Štore”, they would say, when of course it was not even remotely similar. These are all matters of memory, but what cars (especially the lonely rides) do above all is open up space for thought. I can only think while driving, or as Thomas Bernhard put it in Wittgenstein’s Nephew: “The truth is that I am only happy when I am sitting in a car, between the place I have just left and the place I am driving to.” It is not only about the movement but much more about the temporary displacement they offer which makes it possible to dream up all kinds of projects and scenarios. A little bit like in the scene where Philip (Alice in the Cities, 1974, Wim Wenders) alphabetically reads the names of German cities to Alice so she could remember where he is supposed to take her, and she only responds to “Wuppertal” (her nearly last chance), I always wish I could push the final destination slightly further – to a W or perhaps even a Z.

I dreamt you were wearing a black suit

Mar 26, 2020 - Ana Zibelnik

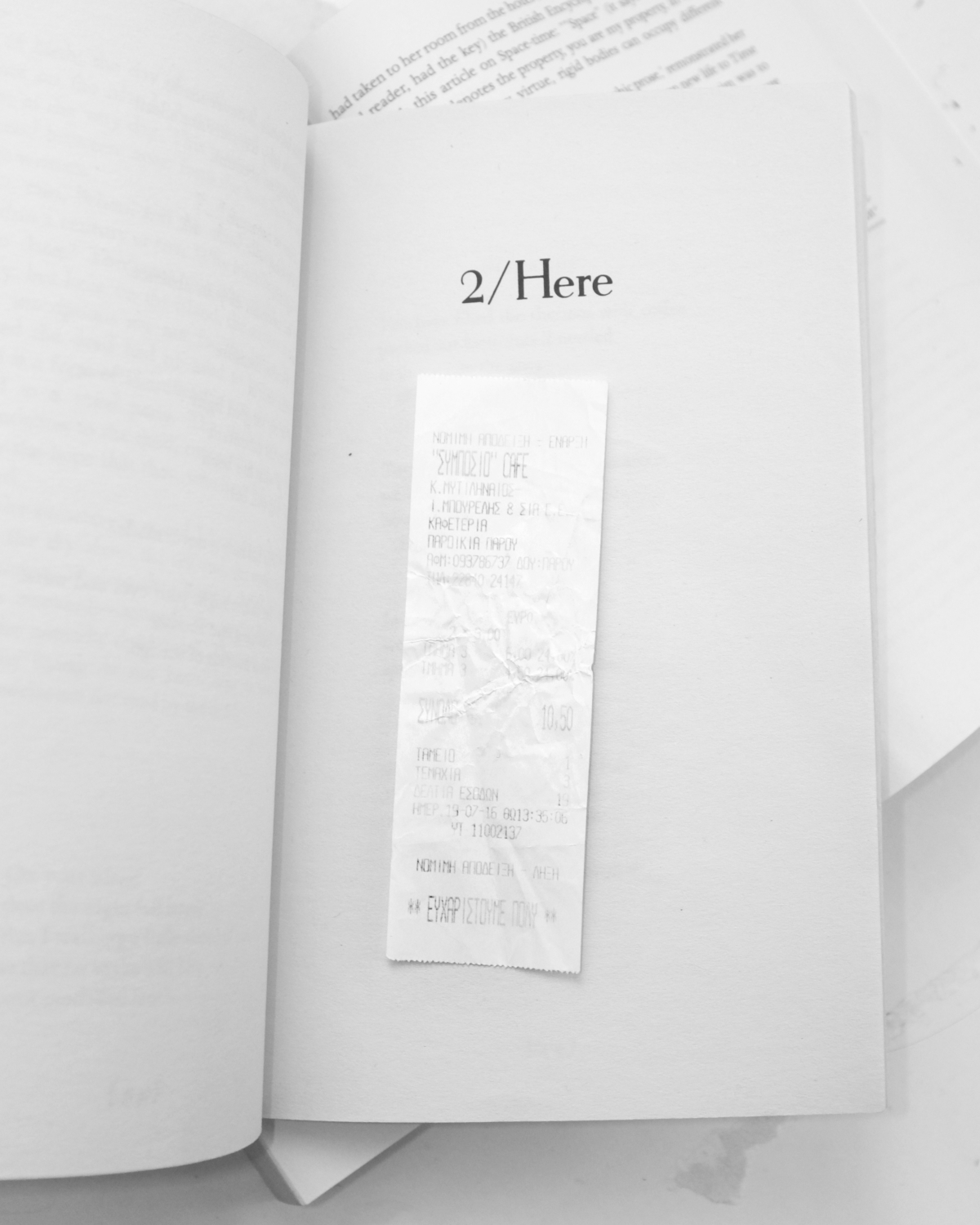

In a song by Narat, a Slovenian singer-songwriter, there’s a line: “dreams are written on the bills”. Inspired by these words, in 2014 or so, I started collecting quotes from books and bits of conversations heard on buses, trains and at cafes, writing them down on the backside of bills – the crumpled pieces of paper one always happens to find in a random pocket. They make for great bookmarks, especially when forgotten or left in books never finished. Finding them years later, one could easily reconstruct a reading map out of the cut-off stories, linking them to places where they were consumed, together with lunches, coffees, glasses of wine or stronger spirits. Why had I stopped at this particular point? Did it bore me, was I so shaken I had to stop or did I perhaps not understand? Most likely I had to leave due to some unrelated interruption, closing the book without even having finished the page. Yet sometimes I would come across a sentence and immediately stop. It would mean I had found it – the image.

I never completely got rid of the habit. Many of my photographs were called into being by exactly such earworm-like sentences, sometimes full passages of books that stuck in my head – with or without context (more often without), of which a common characteristic is a certain sense of mystery, of being unable to properly understand them. It has never been other photographs that would spark my wish to photograph, but words. It is as if what I photograph would make itself visible in the first place only if it resonates with these words. One particular sentence that marked the beginning of a visual direction that We are the ones turning took after failing to be a documentary project is “I dreamt you were wearing a black suit,” which doesn’t even come from a literary work but a phone conversation I heard in 2005. One morning, a relative called, waking up after a weird dream, checking with my father whether he was doing well. The next day, his uncle was found hanging in a shed.