Marinos Tsagkarakis

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

Bucky Miller - The Toad

Mar 04, 2020

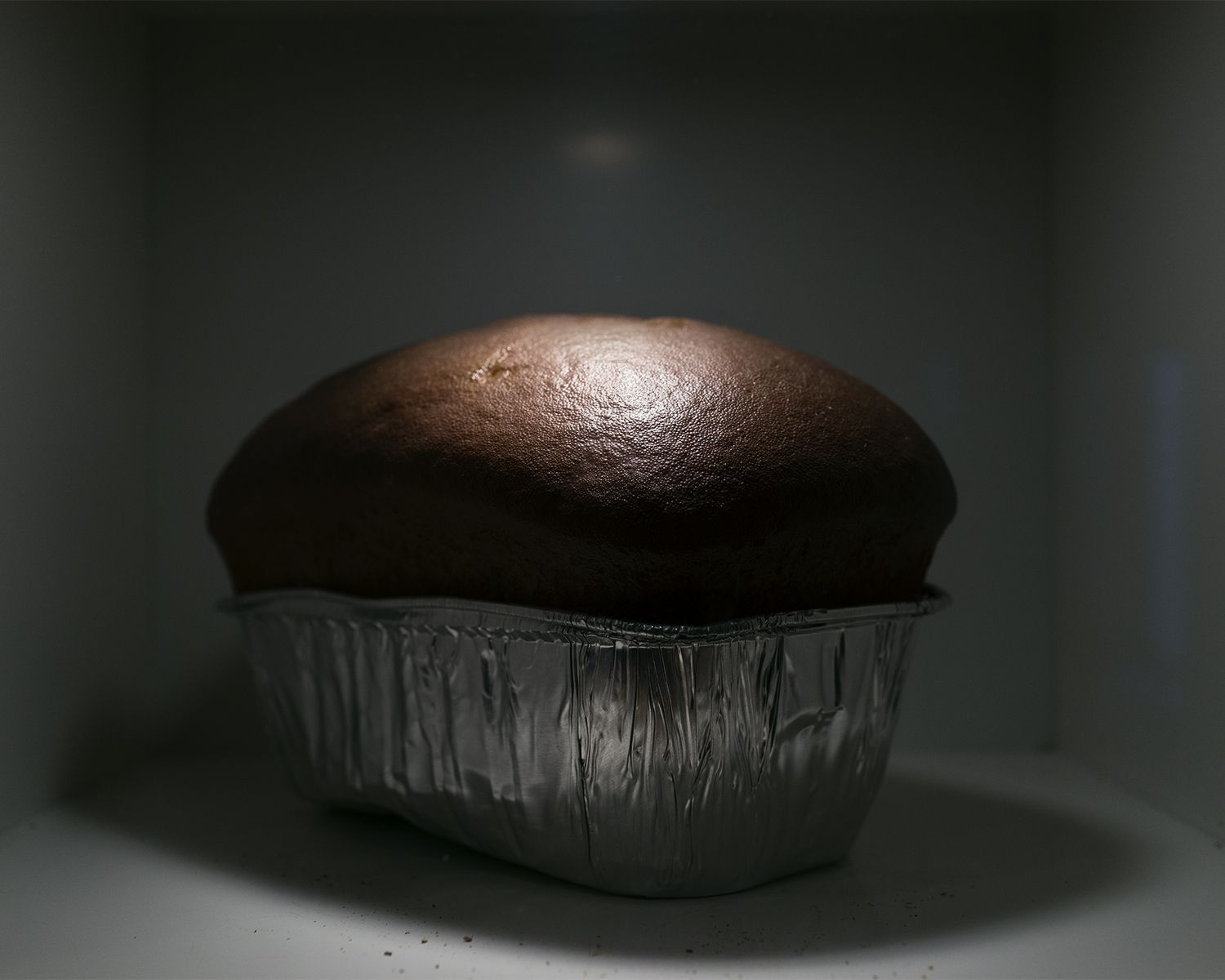

The Toad is a group of photographs dedicated to the toad in Austin, Texas that lives outside my old apartment. I understand that the Toad is actually many different toads, as it changes in size and color, appears in quantities greater than one, dies and come back to life. But beneath the level of rational thought, I am sure that the toads are one entity—the Toad. Very similarly, the photographs in the body of work, The Toad, drift in and out of rationality. They decompose photography’s alleged “documentary” properties into something more affective; less tethered to what happened, they ask what could happen, even if only in one’s mind. The photographs look closely at city animals, not only because the Toad is one, but also because those nonhumans’ negotiation of our shared spaces approximates a photograph’s interpretation of the world more closely than ours does. It seems safe to assume that raccoons notice more in a tree than we can unaided. Yet neither raccoon nor photograph knows a tree is called a tree. Without the burden of language, space becomes feeling. The already dubious, increasingly questioned notion of truth in photography gives way to trustworthy dissonance—we learn, from the Toad, from the photographs, that we cannot know. I love the Toad, but I do not know the toad.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Guest-Room Emma Bowkett«

Canine Fields

Mar 11, 2020 - Bucky Miller

I went to grad school for photography, or rather I was a photographer in an interdisciplinary MFA program at the University of Texas at Austin between 2014 and 2017. The following are two excerpts from the master’s report that I submitted in partial fulfillment of my MFA. I decided to publish it here because grad school is a big weird thing and I thought maybe they could be useful to someone. Maybe it’ll help an artist deciding whether or not to apply, jog some thoughts for a current grad struggling with a thesis, or jeez, just help me. At the time, one of my readers told me, with a vaguely congratulatory air, that I did everything wrong.

It is fun to revisit. The work that wound up becoming The Toad started as my MFA thesis, transforming through time and revision into something that I could not expect at the end of grad school. Some of the facts of the work have changed in the interim. Many of the pictures have been replaced, and, significantly, this essay calls the work Canine Fields. But I had to write this, and think about it quite a lot after the fact, to realize the importance of the Toad to the whole endeavor. The dogs are still important but now they are a part of The Toad.

3. Killing the Father/Myths of the West

Pope John Paul II went to Phoenix in 1987. My parents probably didn’t have much energy for fanfare, what with Daisy, a blind pointer, and me, a very young baby, around. According to Mom, “we watched him on TV at Sun Devil Stadium—people thought that was funny. I remember trying to explain him to you in baby terms. They showed the motorcade to the airport and his plane taking off, so we went and stood on the tree stump as his plane flew really low right over the house. We waved to him. He was a nice pope I guess, as far as popes go, and the whole thing was kind of sweet. I remember you liking it. Why do you ask?”

We lived on Wilshire, at the edge of downtown in a brick house, dotted with citrus, a big tree stump in the lawn. The stump was once a tree, and when I was a newborn that tree was struck by lightning and burst into flames. We watched it burn as a family. The fire department came; the tree was doused but dead, and was soon cut down with a chainsaw. So even though I’ve seen the tree—immolated!—I can only summon a reasonably faithful image of the stump. I was too young for the tree. The tree is a ghost, nothing but a construct of my imagination, some amalgam probably closer to the oaks I see out the window as I write this than the mesquite or whatever it actually was. My images of the fire are from Hollywood—flames a color only found in cinema. Odorless, heatless, a furious cinder-edged tree either far more or far less dramatic than the actual event had to have been.

Recently, home for the holidays, I drove by the old house and saw no sign of any of that; just a low-profile façade of red brick, big dry yard, decorative oranges, newer swing set succumbing to the same sun as everything else but at record speed. I texted someone a picture of the house along with the observation that I’d seemingly spent my childhood living in a Henry Wessel photo. The comment made sense only to me, as only I had spent the first half of my twenties obsessively reevaluating my relationship to Wessel and the other photographers who made up the 1975 George Eastman House exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape. (That’s the show where seven American and two German photographers displayed some modest, straightforward black and white photographs—and one American displayed some modest, straightforward color photographs—of suburbs, industry, and main streets from across the United States and in the process permanently rerouted the discourse around landscape photography.)

New Topographics does not only feel close to me because I grew up in the sprawling West that most of its artists strove to document. The show’s curator, William Jenkins, later became a professor of photography at Arizona State University. He was there as I matriculated. To his credit Bill wonders why there’s still so much fuss about that show, though his objections did not stop its influential ghosts from lingering inside our darkroom. The same deadpan photographs of parking lots and suburban homes surfaced in student show after student show, and I understand why. We were so close to the source. Many of us grew up in those suburbs, and we felt some sense of expertise with regard to their banalities. But these photographs were mostly redundant and—not necessarily the fault of their makers—as banal, as superficially superficial, as their subjects.

One can find a lingering desire through the history of (specifically) American photography, an attempt to express, with some veneer of objectivity, the conditions of the present through precise renderings of place. In her introductory text to the 2010 New Topographics revival catalog, Britt Salvesen charts this continuum:

In an elegant generational cycle, [Walker] Evans was now poised to play for young photographers in the 1970s the role his own nineteenth-century predecessor, Mathew Brady, had played for him in the 1930s, encouraging them, in a time of social crisis, to situate their medium and their subjects in an explicitly American context.

Extending that timeline to the present, almost the same amount of time has passed since the original New Topographics exhibition as separated the New Topographers from Evans. And we are still in a moment of social crisis. But the Brady-Evans-Topographics thread carries, alongside its Americanness, an adherence to a documentary style that is disconnected from the current social tenor.

Today, disarray—charted through an endless network of screens and slogans—may seem the only guaranteed content. Anthropologist Kathleen Stewart’s assertion that “everyday life is a life lived on the level of surging affects, impacts suffered or barely avoided,” is apt. “It takes everything we have,” she says, “but it also spawns a series of little somethings dreamed up in the course of things.”3 These “somethings” should absolutely appear in new photography, but may only do so if the practice is executed with a loose, inclusive approach. The authoritative objectivity that has become associated with American landscape photography suggests a sense of order that is obsolete. Instead we should reach for a disjunctive harmony, where long views, product shots, appropriated documents, and digital manipulation are free to live alongside more traditional pictures. Through this process we may discover that inside the confusion of the present, everything still is made of the same stuff.

This notion carries over into the content of Canine Fields: In one photograph a small white dog in an orange vest is observed in the early stages of becoming a cloud. Elsewhere a cloud of white foam seems on the verge of solidifying into a dog, complete with a bright orange leash. In both of these pictures an entirely organic—borderline magical—process occurs within a cold institutional landscape, without horizon, all linoleum or concrete. The web of associations is dense, generous.

Next time I visit Phoenix I’ll stop and see if the stump has been excavated. It wouldn’t alter the story, but it would be a reminder that change persists when we’re not watching. When the Pope visited Phoenix, to avoid offending the faithful, Arizona State University consented to enshroud every image of Sparky, their “Sun Devil” mascot whose dumb, generic mascot grin was allegedly modeled after Walt Disney, in yellow cloth.

5. The Picture of the Afghan Hound

I found the picture of the Afghan hound at an antique store.

He was staring up at me from a 3×2 inch card, dated 1948, his eyes warm and nearly religious. “Oh hello,” I said in the store to the piece of cardboard, before bringing it home with me for a dollar. Soon the Afghan needed to enter the work. The inclusion felt like a departure, both because the picture is appropriated and because of the direct gaze of the hound. Most of the animals in my photographs exist at a tangible distance—the space between the camera and the creature always makes the seen thing strange. At first glance this doesn’t apply to the incredibly present, iconic hound, but that sense of direct engagement is a ruse. The Picture of the Afghan Hound is much larger than its source, and the dot pattern of the original info card runs interference on a viewer’s interface with the animal. The sense of engagement gives way to a sense of being duped, of being taken in by a duplicate of a duplicate of the image of a dog, long dead, and frankly alien in the world of the photographs. Considering this, it comes to mind that The Picture of the Afghan Hound has a lot in common with a famous Afghan named Snuppy.

Snuppy died a year prior to my writing this. I didn’t know until now. In fact it was only yesterday that I found out Snuppy ever existed, and by then I was 364 days too late to attempt contact. Not that it would have been easy to say hello, what with Snuppy living in Seoul and me hopping around the southwestern United States. Still there would have been warmth in knowing he was out there, the first successfully cloned dog. Now that I know he was, how can I help but miss that warmth?

One tiny solace: apparently there are others. Snuppy’s family, or something. If I try, I can imagine what it would be like to meet these marvels. Licking, sniffing, smelling of dog, their canine natures would overshadow the technological wonder of their existence. I would want to pet them. I would ask permission from a Korean scientist in a spotless, bright white lab coat, and I would pet them. I would say, in a tone similar to the one I would use with a person, “Oh hello. How are you? You are a nice dog.” Meeting those clones would be lovely, in spite of the mystery, but I admit to heavy bias. Far as I can tell there is always mystery in meeting an animal, and it is always lovely.

For instance, take the Toad. I do not know the Toad, but it has lived in a crack on my front porch since I moved to Texas. On warm nights it crawls out and sits perfectly still on a step, waiting. When I come home from grad school I say, “Hello Toad,” before I go inside. Sometimes I’ll come back out in slippers and stare at it, or take its picture, or laugh. It usually doesn’t budge, which is fascinating. There is no fear. I love the Toad, but I do not know the Toad. I cannot, but this has almost nothing to do with the fact that I am human and the Toad is toad. It has a little to do with distance, and with language, but mostly it has to do with the fact that the Toad is a shapeshifter; it is sometimes brown, sometimes gray, sometimes it is the size of my fist and sometimes it is the size of a key fob. Sometimes it is even two toads, and on one wondrous occasion it was three. How could I ever expect to familiarize myself with such trickery?

Here’s the nearest I can get with language: I know the Toad is like The Picture of the Afghan Hound, and I know they are both like Toad, which is my best approximation of the Toad in photograph form. All three challenge indexes, just as indexes begin to feel understandable. These challenges are the system on which Canine Fields is built. It is a shaky foundation, doomed to crumble over and over, but of course it is. Those surging affects, those lost and hidden things, they’re damn persistent.

Review of Menil Collection Exhibition: Photography and the Surreal Imagination

Mar 10, 2020 - Bucky Miller

It was California weather in Texas, and seventy five people were on dates in the park outside, pets, pizza, frisbees, blankets, and big hats. They moved the Magrittes out into the lobby for Photography and The Surreal Imagination. The exhibit took over three small galleries, sorted thematically. The first was called The Body, the second The Image, and the third was The Everyday. The walls were blue-gray. In The Image, a large winged ant crawled diagonally downward across a framed photograph. I stood there with my open notebook in my hands.

The security guard mistook my watching the bug for a very close examination of the picture and asked if I was a photographer.

“Yes,” I said.

“Man Ray is over there. Enjoy—this exhibit is on loan.”

“Oh really?”

“It’s a temporary exhibit—enjoy.”

I thanked him and stepped obligingly toward the Man Ray as I tallied the number of security guards in my book.

“You can take pictures of the labels,” he said.

“But not the work.”

“When I’m not looking.”

I laughed and thanked him again.

“Most are loaned by the artists or somebody.”

“I see.”

“Enjoy.”

Smiling, I thanked him and moved into The Everyday. Atget and others. Since leaving college I have missed being surrounded by people who care deeply about photography, who want to see it pushed to its wondrous best. Going to look at art never parallels the experience of sitting in a dark room and arguing with people you love. But The Everyday got me close. Seeing Lisette Model and Cartier-Bresson in the context of The Surreal Imagination validated some old recurrent feelings of mine around how photography always harbors a massive, fundamental, strangeness. All the pleasures that can be found swirling around inside a constructed image are also intrinsic to nature. The preverbal impulse to record an image knows no restraints. There are so many reasons to keep our parameters broad.

I thought up a show called Surrealism and the Photographic Imagination and closed in on the last picture in the exhibition, which was Diane Arbus’s famous boy with a grenade. He’s always wearing that frustrated grimace; he was staring me straight in the face. In this context his one empty claw stretched to its limits in an attempt to grasp my take on the show. Outside, a clean dog chased a squirrel up a fig tree.

Some Hidden Language

Mar 09, 2020 - Bucky Miller

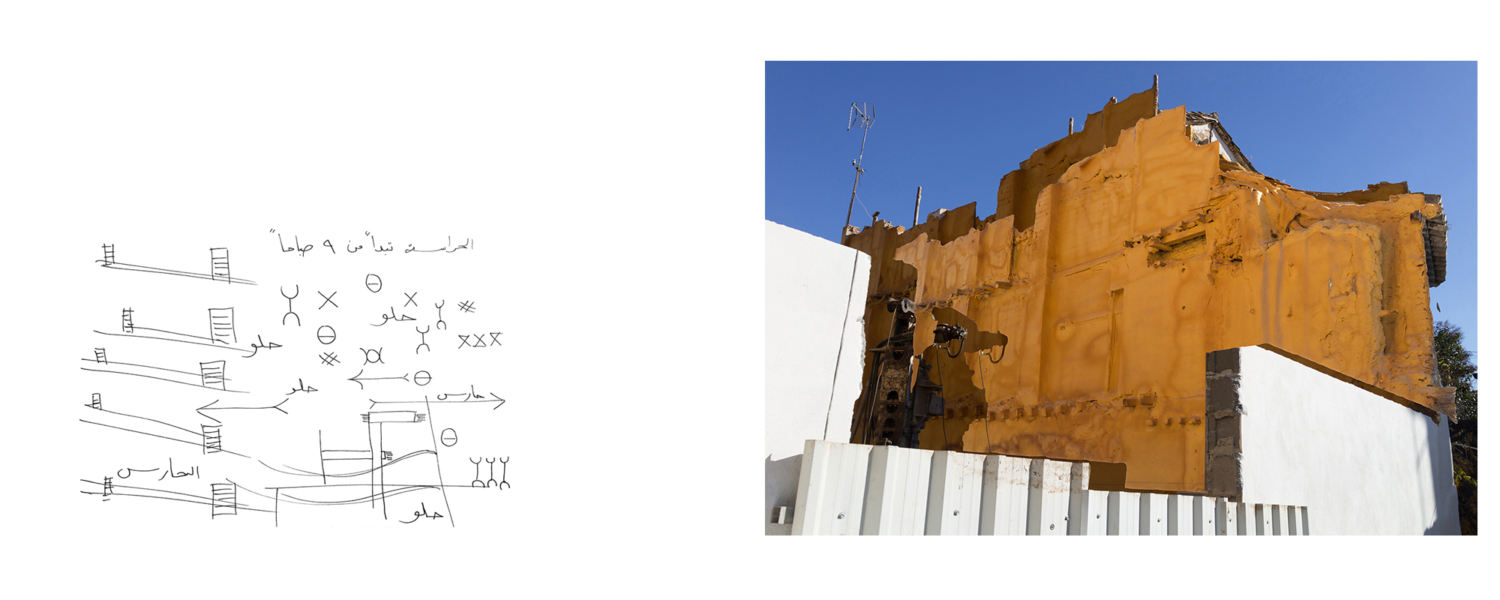

Nidaa Aboulhosn tends to bundle her photographs into carefully crafted groups that glide into a viewer’s consciousness with a subtle and satisfying version of the “it was your house but not your house” component of dream logic. In fact, she describes her working method as akin to decorating a home: Instead of just pulling in all your belongings at once, you start with a few nice pieces of furniture. Those will tell you what else you might need, so you go out and get them. She photographs in locations from Lebanon to Mexico to Morocco and then returns to her studio in Upstate New York to learn from the work. The resulting sequences often describe places that are not geographic but photographic. That, to me, is cool. She is also a valued friend. We should all count our friends among our favorite artists. We should interview them when given the chance.

I called Nidaa in Ithaca and we spent an hour on speakerphone with my computer recording as I ate a sweet potato. We began the conversation by talking about whether photography was a language. She said absolutely, in fact she was teaching a class on the language of photography at Cornell. We discussed a specific sort of coded language that inhabits and helps define her recent photographs. Nidaa’s pictures poeticize photo-language, but there is often a second language inside them. This is a bottled up text made of symbols and fugitive marks that communicates to the photographer and her subjects but is generally cryptic to the viewer. Recently, she started making drawings of elements from the photographs, and then photographing those drawings. We really unpacked this stuff. It was a fantastic conversation. My recording failed to save and I lost the entire interview.

I sent her a text: “It didn’t work and frankly that makes me very sad. I will do my best to write something good.”

“I know you will. But what a bummer & how weird,” she replied.

The next morning I awoke to an email from Nidaa:

“I wanted to try to recall what we talked about before I go to bed while it’s still somewhat fresh in my mind. It’s not that fresh—it’s gotten a bit stale. Anyway, I recorded a voice note about 9 minutes long highlighting the key things we discussed. Here it is.”

There was no attachment on the email, no audio track to be found. I wrote to ask if she could send it again. She said she had already deleted it. She sent me a fresh twelve minute recording but suggested I not listen to it until I finished writing this piece. A copy of a copy of a copy.

Obliging, from a borrowed garage apartment in a nice part of Houston, audio file resting in my inbox, I thought about my friend, her words about her pictures, their language. To feel safe in the unknown, it helps to have a guide. Nidaa’s photographs move the oblique to a position of comfort. Urgent scribbles in handwriting and architecture are revealed as the common babbling of the world, and we are made to feel a little less alone. We are small, but we are all small. There is room to laugh within whatever we are trying to accomplish.

But then I had to go to work, and so on. My thoughts got a bit stale. I figured Nidaa should get the last word:

“I hope what I am saying, recalling, does not contaminate or distort your memory. So, you collect these stacks of images. When reviewing them you discover what you are paying attention to. You realize there is an intelligence, a method behind the way you are photographing that you may not have known if you set out to photograph a specific subject. You learn something about yourself. There is an unconscious, hidden knowledge that I unearth after I make the work and then it is, ah! ok. That is what I have been searching for. There was a lot of talk about why I do not make work in Upstate New York. Squirrels—just trying to jog your memory.”

Review of the Photography Section at the Half Price Books Near My Apartment in Houston

Mar 08, 2020 - Bucky Miller

My first year in Houston I lived more or less in the Museum District, which put me within walking distance of at least four organizations that regularly exhibited photographs. There was also a branch of Half Price Books, a big-box used book buy-and-sell operation. I often walked over to check out their photography section, hopeful that some curator emeritus, discouraged by the direction of whatever local institution, had given up and unloaded a pallet of scarce old photobooks at the shop’s doorstep. I checked earlier today.

Photography is one shelf over from art, and shares a cramped, dead-end aisle with architecture. It is this way at every Half Price Books I have ever visited. I breezed past the endcaps, which always overflowed with remaindered copies of Hollywood portrait books and lists of art to see before dying, heavy things destined to be pulped. In the aisle, sitting in a chair in the corner, was an old man. He was hunched over a large book that contained pictures of houses. Where did he get the chair? He was wearing a blue cap, faded denim shirt, old jeans and running shoes. Head to ankles blue, with a white beard tumbling halfway down his chest in tight curls. I could hear him breathing. He exchanged the house book for another very large volume, this one of portraits. I pretended he was some noteworthy artist from a previous generation, maybe somebody whose silver prints were in the collection of the Museum or whose monograph was right here in front of us. The shelf above his head was half Ansel Adams and half Diane Arbus, including six copies of two different versions of her biography. I was nervous to disturb the man, to stand too close. I studied his Wayfarer sunglasses, which were resting on the shelf atop a row of squatty Lee Friedlander books. He obstructed my view of photographers last name G-J. That was fine. The second half of the alphabet was satisfactory.

Eadweard Muybridge was misshelved in two different places.

Instead of focusing on titles or artists, which seemed to be mostly 20th century American, I glazed over and thought about the scale of the books. They were nearly all humongous. Why has the photobook so often commingled with the coffee table book? The idea is probably that it allows the picture to be larger on the page, but I question the value in that. So many photographs have led beautiful lives inside wallets. I always wish for more book-sized books. Pictures are less demanding, yet more confident, when they are easier to hold. Readers can drift through the work as if absorbing a chapbook without being made to feel they are in church.

There is also the fact that I am at a stage of my life when I move too often. Boxes of books are heavy. I keep this one gigantic cardboard box around in order to transport the largest photobook I own, Peter Fraser’s eponymous thing, a square maroon one with a paper airplane on the cover. Unfortunately I really like the book, so I keep moving it. The box came from Target and originally carried bedsheets through the mail. Since it is the only box I have that fits the Peter Fraser, I wrote BOOKS on the side with a sharpie and I fill it to the brim with books every time I move. It becomes heavy. Meanwhile Ruth Van Beek’s The Levitators is essentially a steno pad, and it is brilliant. Plus I can slot it right alongside my science fiction paperbacks. What I am saying is artists and designer should, can sometimes, be considerate when dealing with good photographs.

The Half Price Books had no Peter Fraser or Ruth Van Beek. It might never. In fact, nothing at all leapt out from the blur of titles. I glanced at the bottom shelf, the one for especially oversized books, and inhaled. As I walked out of the aisle, the bearded man continued to flip through books. Horst. He seemed remarkably content.

Let’s Break Instagram

Mar 07, 2020 - Bucky Miller

Instagram is the dumbest imaginable proof of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy speculations about the significance that photographic literacy would possess in the future. But it is absolutely photography. So what can we, as people who care about photographs, do with Instagram?

Not too long ago I attempted to write an essay about an Instagram account called @garfields_i_found_on_ebay, which, as the name suggests, aggregates photographs of toy Garfields from eBay listings. I was about 4,000 words deep into a strained attempt to weave the history of appropriation art with the superficiality and instant gratification of the Instagram interface when I realized what I wanted to say didn’t actually have that much to do with Garfield, or appropriation, but was really just about the platform. The excitement from @garfields_i_found_on_ebay is in the total lack of beauty or nuance in any of the photographs on the feed. eBay is a holdover from an earlier form of internet. Its blunt, descriptive, often ugly photographs cudgel the synapses when slotted in between the hyper-aestheticized imagery of the present moment.

Instagram is a corrosive platform that I enjoy daily in the only appropriate way, i.e., with pathological fervor and self-resentment. The longer I stay there, the more I become convinced that the best way to engage is to mutilate the feed. We should post slow videos that go nowhere. Deadpan pictures with no connotations, made from the deepest depths of boredom, incapable of generating any fear of missing out. Memes do something parallel to this, I think, and their anonymity allows them to become communal property. But the democracy of memes does little to overpower the rest of the feed and the focused negative emotional impact of the influencer, of the friend on vacation, the successful artist or ex-love. The algorithm may fight us, but only by pushing the medium as deep as we can into pure meaninglessness can we triumph over the capitalistic diseases of alienation and self-doubt!

A disrupted feed has the potential to transmogrify the social media platform most plagued by obsessive rise-and-grinders into something closer to a crowdsourced exquisite corpse whose unlimited participants collectively acknowledge the strangeness of the day—a truly ecstatic possibility. It seems difficult to achieve—and posters must find their own ways through—but it is attainable. My feed is not there yet, because I like my friends and will not tell them what to post. But maybe they will read this. Maybe they will be the only ones who read this. Hi, friends.

The Darkroom Monitor

Mar 06, 2020 - Bucky Miller

The Darkroom Monitor showed up to the photography building at the university a half hour late.

The Darkroom Monitor apologized to the outgoing darkroom monitor.

The Darkroom Monitor looked at his phone.

The Darkroom Monitor entered the darkroom.

The Darkroom Monitor looked at the students printing.

The Darkroom Monitor jiggled the fixer.

The Darkroom Monitor exited the darkroom.

The Darkroom Monitor looked at his phone.

The Darkroom Monitor wrote his phone number on the dry erase board.

The Darkroom Monitor went to get coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor ran into Abe while getting coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor listened to Abe complain.

The Darkroom Monitor ordered coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor sympathized with Abe.

The Darkroom Monitor winced from the temperature of the coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor said the word “scalding.”

The Darkroom Monitor asked Abe about the symposium.

The Darkroom Monitor made a mental note about the details of the symposium.

The Darkroom Monitor walked back to the photography building.

The Darkroom Monitor entered the darkroom.

The Darkroom Monitor exited the darkroom.

The Darkroom Monitor drank his coffee in the corner.

The Darkroom Monitor texted Abigail about the print sale.

The Darkroom Monitor texted Abe about the symposium.

The Darkroom Monitor texted someone on the other side of the country about a political candidate.

The Darkroom Monitor looked at Abe’s text, which regarded the symposium.

The Darkroom Monitor waited for texts from Abigail and someone on the other side of the country.

The Darkroom Monitor confirmed his number was still written on the dry erase board.

The Darkroom Monitor walked to his car, drinking his coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor got in his car, turned on the ignition.

The Darkroom Monitor drove towards the highway.

The Darkroom Monitor drove straight into the next town.

The Darkroom Monitor heard his phone vibrate.

The Darkroom Monitor saw a billboard advertising a political candidate.

The Darkroom Monitor tempted fate by checking his phone while driving.

The Darkroom Monitor read a text from Abigail that said: yes

The Darkroom Monitor saw a billboard advertising a political candidate.

The Darkroom Monitor saw a billboard advertising DOG BITE ATTORNEY.

The Darkroom Monitor exited the highway in the next town.

The Darkroom Monitor drove around the block a couple of times.

The Darkroom Monitor heard his phone vibrate.

The Darkroom Monitor parallel parked.

The Darkroom Monitor heard his phone vibrate four or five times.

The Darkroom Monitor read a string of text messages from someone on the other side of the country, complaints about a bagel.

The Darkroom Monitor walked into the building.

The Darkroom Monitor waved at Abigail.

The Darkroom Monitor saw Abigail wave at him.

The Darkroom Monitor walked towards Abigail, who walked toward the Darkroom Monitor.

The Darkroom Monitor related to Abigail what Abe had told him about the symposium.

The Darkroom Monitor heard Abigail say she knew that already.

The Darkroom Monitor felt self-conscious.

The Darkroom Monitor felt his phone vibrate in his pocket four times.

The Darkroom Monitor drank his coffee, which was now lukewarm.

The Darkroom Monitor looked at the art on the walls.

The Darkroom Monitor recognized prints by Abigail.

The Darkroom Monitor saw a monoprint by a high school painting teacher that depicted cartoon fellatio.

The Darkroom Monitor wandered around.

The Darkroom Monitor admired a picture of a dead duck, by Abigail.

The Darkroom Monitor wondered how much money he should be spending on art.

The Darkroom Monitor purchased one of Abigail’s prints, a dead grebe.

The Darkroom Monitor justified his purchase to himself by reminding himself he was on the clock.

The Darkroom Monitor said you’re welcome to Abigail.

The Darkroom Monitor threw away his empty coffee cup in the bin near the front door.

The Darkroom Monitor walked back toward his car with Abigail’s print, in plastic, under his arm.

The Darkroom Monitor read texts from someone on the other side of the country about a political candidate.

The Darkroom Monitor heard Moby playing.

The Darkroom Monitor stopped at the cafe that was playing Moby.

The Darkroom Monitor walked up to the barista.

The Darkroom Monitor recognized the barista.

The Darkroom Monitor ordered an iced coffee from Moby.

The Darkroom Monitor watched Moby pour his iced coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor tipped Moby $1.

The Darkroom Monitor commented on the strength of the iced coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor watched Moby shovel more ice cubes into his coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor sat down.

The Darkroom Monitor drank his iced coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor disliked the art in the cafe.

The Darkroom Monitor disliked the chairs in the cafe.

The Darkroom Monitor texted someone on the other side of the country about the cafe’s bad chairs.

The Darkroom Monitor texted Abigail a picture of her own artwork in his hand.

The Darkroom Monitor texted Kevin about a political candidate.

The Darkroom Monitor texted Abe about Abigail.

The Darkroom Monitor texted Valerie about god knows what.

The Darkroom Monitor read a text from someone on the other side of the country about poetry.

The Darkroom Monitor texted someone on the other side of the country about poetry.

The Darkroom Monitor put his phone face-down on the table.

The Darkroom Monitor saw some customers enter the cafe and not recognize Moby.

The Darkroom Monitor drank his iced coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor took out his notebook and began to write ideas.

The Darkroom Monitor heard his phone vibrate twice.

The Darkroom Monitor looked at a cat outside.

The Darkroom Monitor wrote some more ideas in his notebook.

The Darkroom Monitor watched the cat enter the cafe.

The Darkroom Monitor took a digital camera from his pocket.

The Darkroom Monitor heard his phone vibrate four or five times.

The Darkroom Monitor photographed the cat ordering a drink from Moby.

The Darkroom Monitor sipped his iced coffee.

The Darkroom Monitor knew his shift would be over soon.

The Darkroom Monitor heard his phone vibrate.

The Darkroom Monitor put away his notebook and his camera.

The Darkroom Monitor walked back to his car.

The Darkroom Monitor drove back to the university.

The Darkroom Monitor passed a Chevy Aveo on the highway.

The Darkroom Monitor heard his phone vibrate.

The Darkroom Monitor paid for parking.

The Darkroom Monitor found the photography building empty.

The Darkroom Monitor realized his shift ended a half hour ago.

The Darkroom Monitor erased his number from the dry erase board with two fingers.

The Darkroom Monitor greeted the oncoming darkroom monitor.

The Darkroom Monitor accepted the oncoming darkroom monitor’s apology for tardiness.

The Darkroom Monitor looked at his phone.

On Walker Evans

Mar 05, 2020 - Bucky Miller

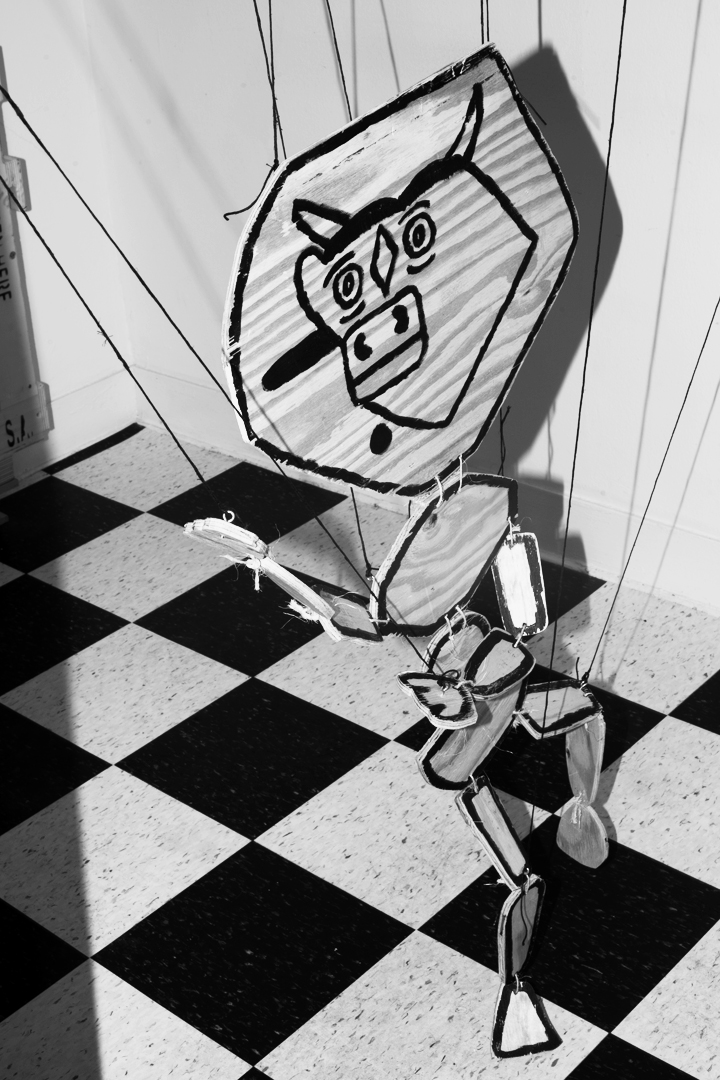

Last year I came up with a story about Walker Evans, about how when he died, instead of just straight-away dying like most of us do, he was transformed into a marionette version of a cow from one of his own photographs. The picture is called Butcher Sign, Mississippi, 1936, and it is one of the stranger photos from Walker’s best known era. It shows a painting on a brick wall of a stunned cartoon cow with white horns, bangs, and a mystery appendage emerging from just below the ear. Whenever I draw the cow, people mistake it for a Picasso. Guernica, I think, which is dated 1937. It is doubtful, but maybe Picasso saw the Evans photograph. More likely the paintings just share a common flatness, a common bovinity.

I imagined Walker Evans waking up the morning after his fatal stroke, brushing a rusted machine screw from his forehead, and realizing that his face had become two-dimensional in the night. He would look in the mirror and realize he was now a cow puppet, then collect himself with stoic resolve. From there, for Walker, it would be business as usual.

But the press would have a field day. “Walker Evans is a cow from one of his own photographs now. What an unexpected development!” I have to think the history of photography at Yale would be a lot different, had this been the case.