Olivier Lovey

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

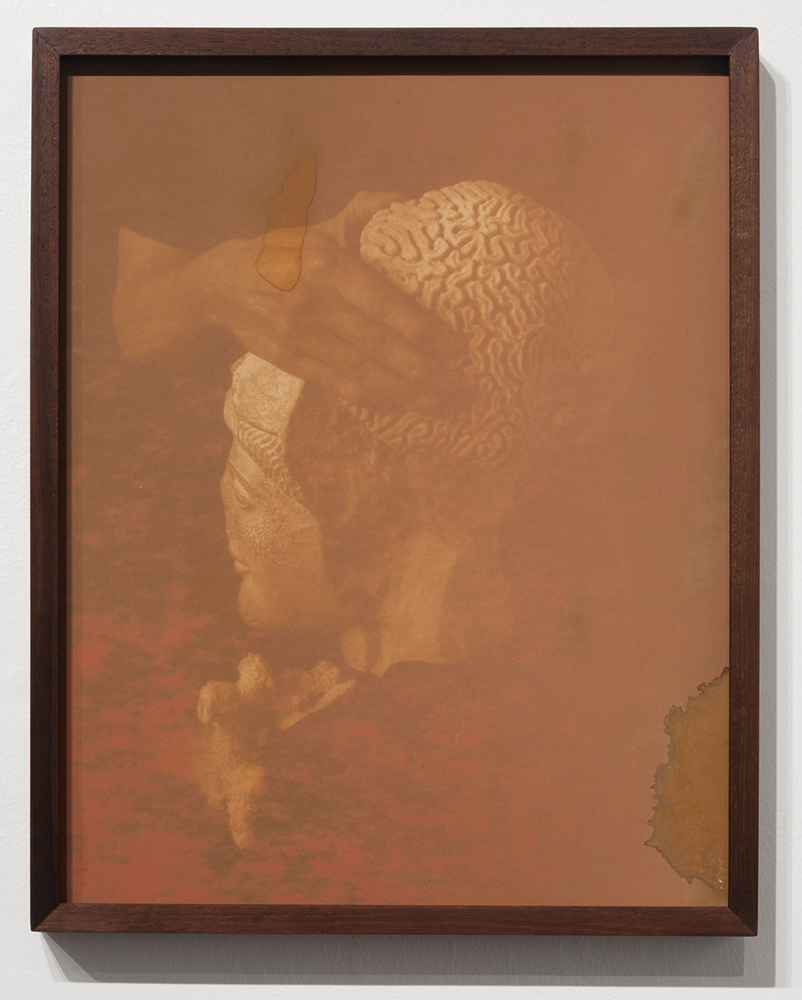

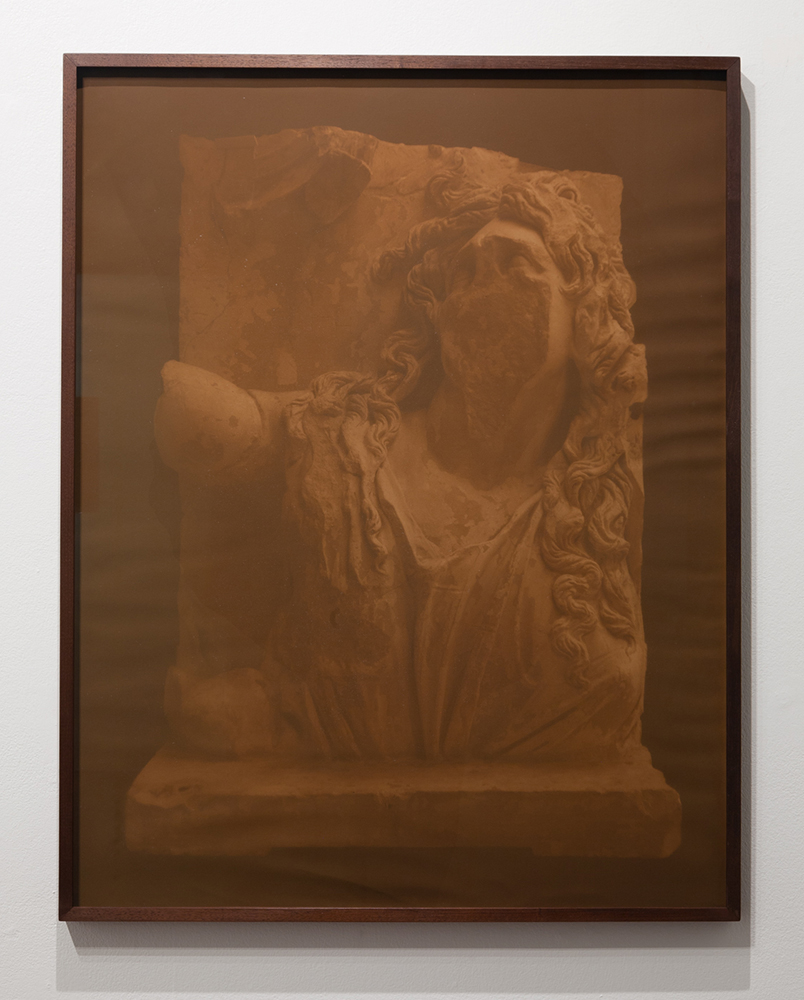

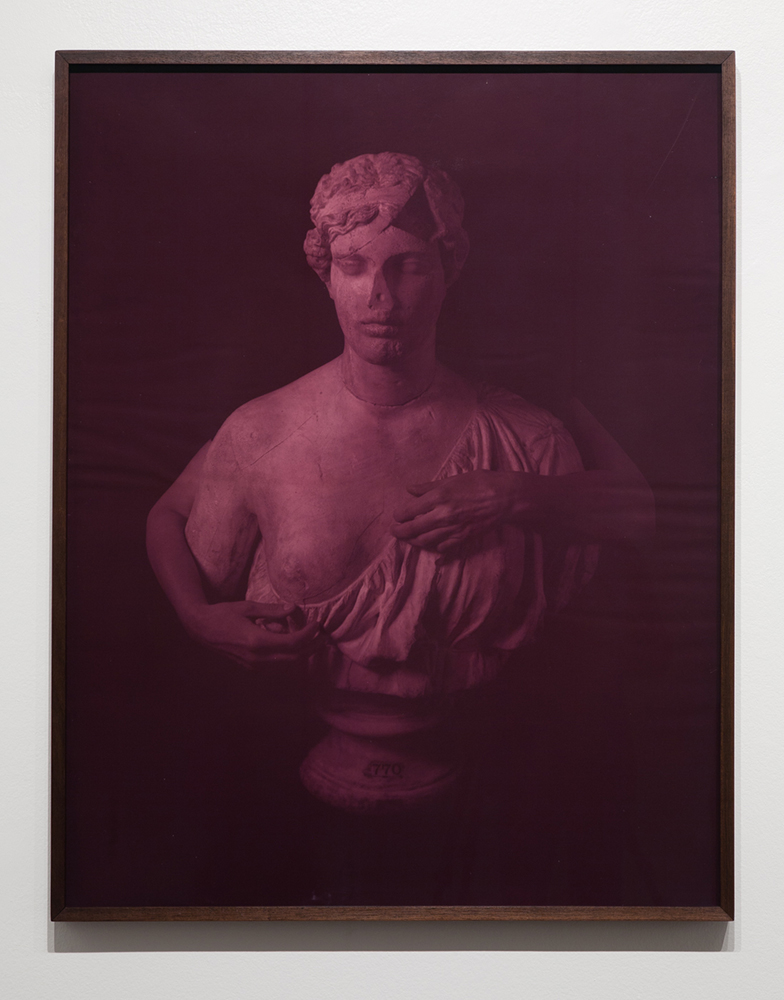

Christine Elfman - Objects Apparitions

May 02, 2018

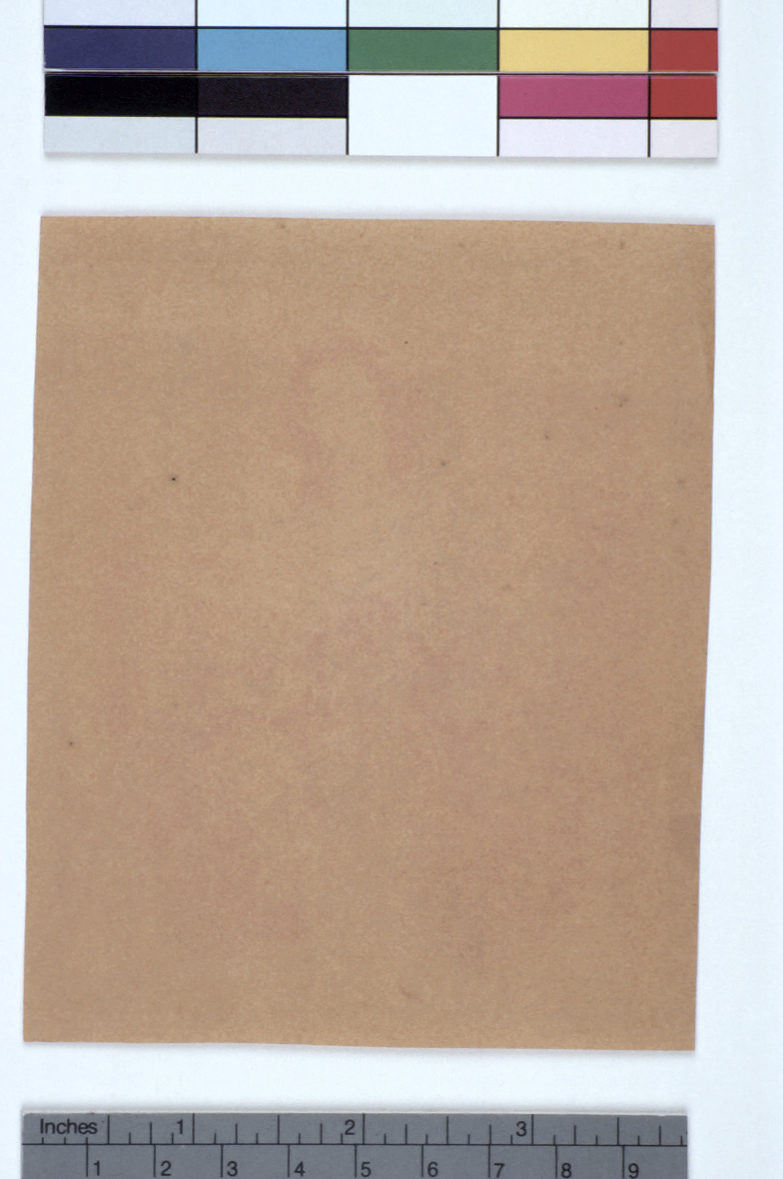

These photographs embody the temporal wane of objects, images, and memory. Color slips from the surface of paper, subjects become shadows, recognition fades into lore. Using the anthotype process, the images develop slowly: sitting outside for a month, the sun bleaches paper saturated with light-sensitive plant dyes.

Once complete, the photographs will continue to fade from the light that allows them to be seen. When paired with fixed silver gelatin prints, they reflect a tension between the archival impulse and the ephemerality of photographs and their subjects. Over time, objects and images become evidence of nothing but the impossible desire for permanence.

Emphasizing the tension between recognition and entropy, the works offer a rare opportunity to witness the constant cycle of growth and decay, as the images are continuously made anew as they decline. While the gaze of the viewer witnesses the gradual destruction of the image, the photographs begin to mimic the shape-shifting apparitions of recollection and reminiscence.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Guest-Room Charlotte Cotton«

Look away or close your eyes

May 09, 2018 - Christine Elfman

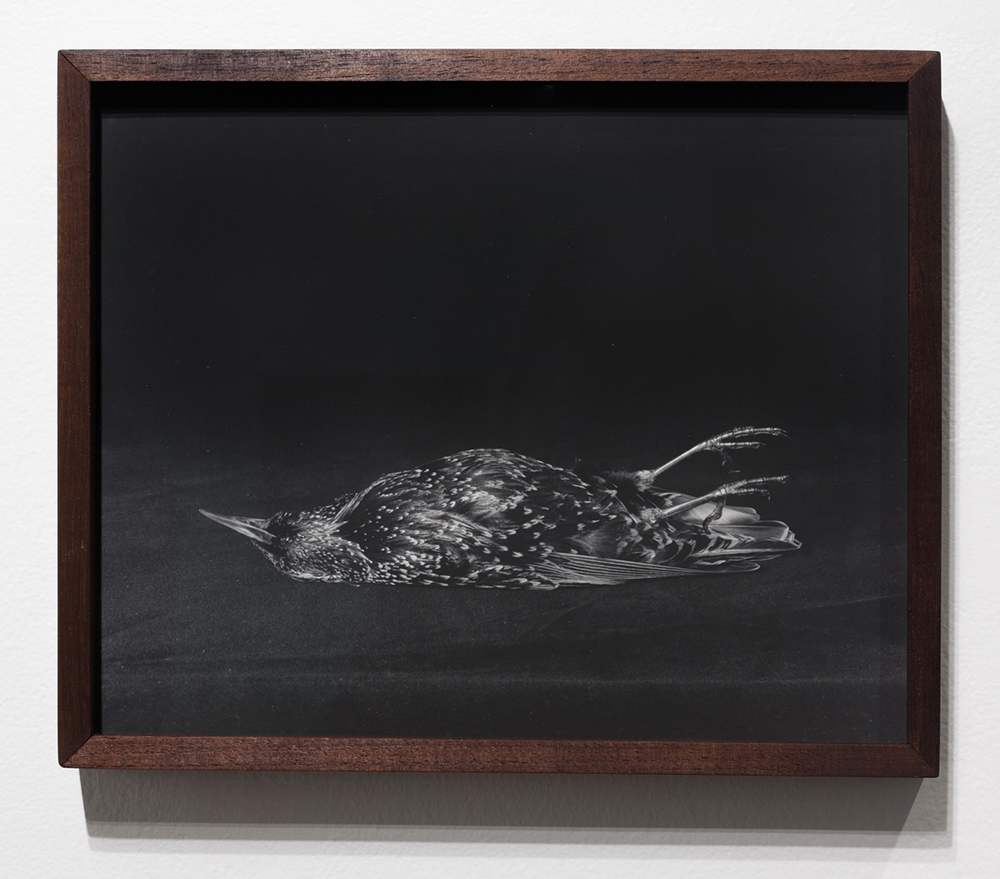

Picture taking sacrifices the subject of the photograph in the present, in order to keep it for the future. It’s like catching a bird for a collection. Once you’ve caught it, it changes, so you’ve never really got it. And even when we think we captured a likeness, eventually we have to distance ourselves from the picture in order to recognize it again.

Looking at pictures is like listening to music. Emotions get worn out, we become desensitized. Sometimes we keep things out of sight, so they don’t lose their impact. So we put it in a box or a drawer or leave it on a hard drive or in the cloud not knowing if we’ll ever see it again. And then maybe years later we look for it, or just let it go. I agree with Roland Barthes when he writes, “I may know better a photograph I remember than a photograph I am looking at….Ultimately – or at the limit – in order to see a photograph well, it is best to look away or close your eyes.”

Maybe the reason people use the words nostalgia and sentimentality pejoratively is because holding on to things too tightly kills them. Photography reminds me of the stories in which people turn to stone when they look back, it petrifies its subjects. If we want the visual evidence, we lose something. Like Orpheus, we lose Eurydice when we look back to verify her presence. I try to remind myself that just because I can’t see something, doesn’t mean it’s no longer there.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius might as well have been a giant photographic flash.

May 08, 2018 - Christine Elfman

What if they turned to stone when they were photographed? It’s as if the desire to capture the likeness, petrified the person. This seems like all the photograph can offer: a stilted cast of the past. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius might just as well have been a giant photographic flash. And when I look at Sommer’s picture, it’s as if I can feel the volcanic impact, like sunburn or nuclear radiation on the skin. The highlights in this albumen print have faded over time, and seem like a photographic overexposure. But really it’s just the gradual fading of the print over time.

Many of my subjects are plaster casts of statues, copies of a copy of a copy, with exacting indexicality. These statues are printed human life-size, so the viewer might imagine them as people that have been petrified by the camera, as if they were punished for nostalgia. On the surface, these photographs might seem conventional, however this conservatism is complicated by the fact that the images are gradually disappearing. The beauty functions as a hook, making their unattainability all the more relevant. If the viewer is seduced by their beauty, they are reminded that it is impossible to fully possess them.

People often ask me how long it will take for them to fade away. The answer depends on context, on how they’re handled and where they live; it’s the same for our own bodies or anything else for that matter. We can never see a wrinkle actually appear on our skin. Things are always changing slowly and imperceptibly. Photographs are what we’ve come to rely on for a visual reference point, to actually perceive the passage of time.

The photograph is a pitfall trap.

May 07, 2018 - Christine Elfman

This photograph of mine is of a pitcher plant specimen encased in resin. The silver gelatin print shows the subject life size, and is colored out of the same fading dyes I used for the anthotypes in the Objects Apparitions exhibition. When I photographed this object, I didn’t know much about pitcher plants. It reminded me of a bodily orifice, and I thought, well, this is the type of subject that draws one in. After I made the work, I was researching pitcher plants and learned that they are carnivorous plants that lure their prey inside with the use of beauty, texture, color, and sweetness. Once the insect is trapped, their body gradually dissolves. This seemed like the perfect metaphor for a photograph. The photograph is a pitfall trap. It seduces the viewer with color, texture, fine details. And when the viewer is absorbed in the picture, they gradually dissolve. The photograph becomes the captor instead of the captive.

Lady with beads

May 04, 2018 - Christine Elfman

Here’s another anthotype made by Herschel on March 10th, 1842. It’s a ghost of a lady with beads made of faded red stock flowers. The difference in condition between this and the “best surviving specimen” could be explained by the fact that some flower dyes are more stable than others. But I prefer to think that someone was obsessed with this lady with the beads, and kept sneaking peeks at her, and every time they looked at her she faded away a bit more.

The anthotype is interesting because its fade is inherent and unavoidable. It’s something that is made out of fading. The fading isn’t a special effect or filter.

There are many photographic processes that you can purposefully undermine by not fixing. However, the anthotype is actually made out of the decay and does not offer a permanent option. Its not just about fading, it is fading. The more you look at it the faster it disappears. I like to imagine someone living with an anthotype displayed long enough that the image becomes invisible. Then a visitor might see an empty frame hanging in their room, and ask, “Why do you have a blank picture hanging on your wall?” And then they could tell them what it used to be like. The image becomes visible only as a story or memory.

Grecian lady looking at the moon

May 03, 2018 - Christine Elfman

Henry Fox Talbot was frustrated by fugitivity. He complained that his images were “fairy pictures, creations of a moment, and destined as rapidly to fade away.” And then, Sir John Herschel came to his rescue, and suggested he use sodium thiosulfate to remove the unexposed silver, and in doing so, gave us all the ability to fix our pictures. Thanks Sir John! Every time I use fixer I remind myself to try and not take it for granted, to remember what it is.

And for all his heroism in the fight against fugitivity, Hershel also invented an especially unfixable type of photograph, the anthotype. In 1841, he coated paper with the juice of flowers and then exposed a waxed engraving in contact with it to the sun for a few weeks. He made photographs through the action of sun fading the impermanent dyes. It’s really as simple as the color of curtains fading in a sunny window, or the way posters in shop windows eventually turn cyan. But of course, the process never became popular, since it fails to meet the primary criteria for a photograph, stability. Many of these anthotypes are still visible after 177 years, since they’ve been kept in the dark.

Here is “the best surviving specimen” in the collection of the Oxford Museum of the History of Science. It’s a Grecian lady looking at the moon, made of faded crimson poppy dye by Herschel in 1841. Maybe this specimen is so well preserved because it was only viewed by moonlight. Is it significant to note that the digitization process, if only imperceptibly, compromised this object for the sake of visibility and accessibility?