Anna Ziegler

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

Diego Ballestrasse - The Fourth Wall

Nov 30, 2016

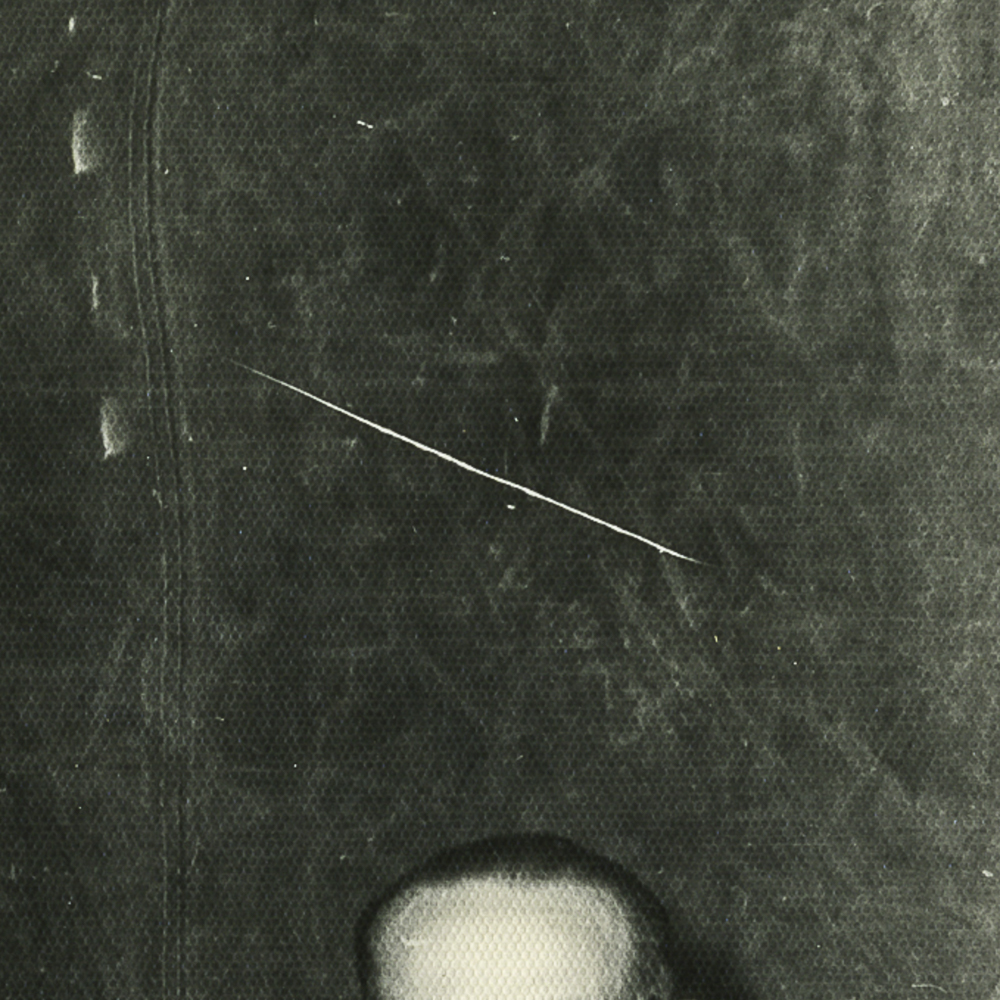

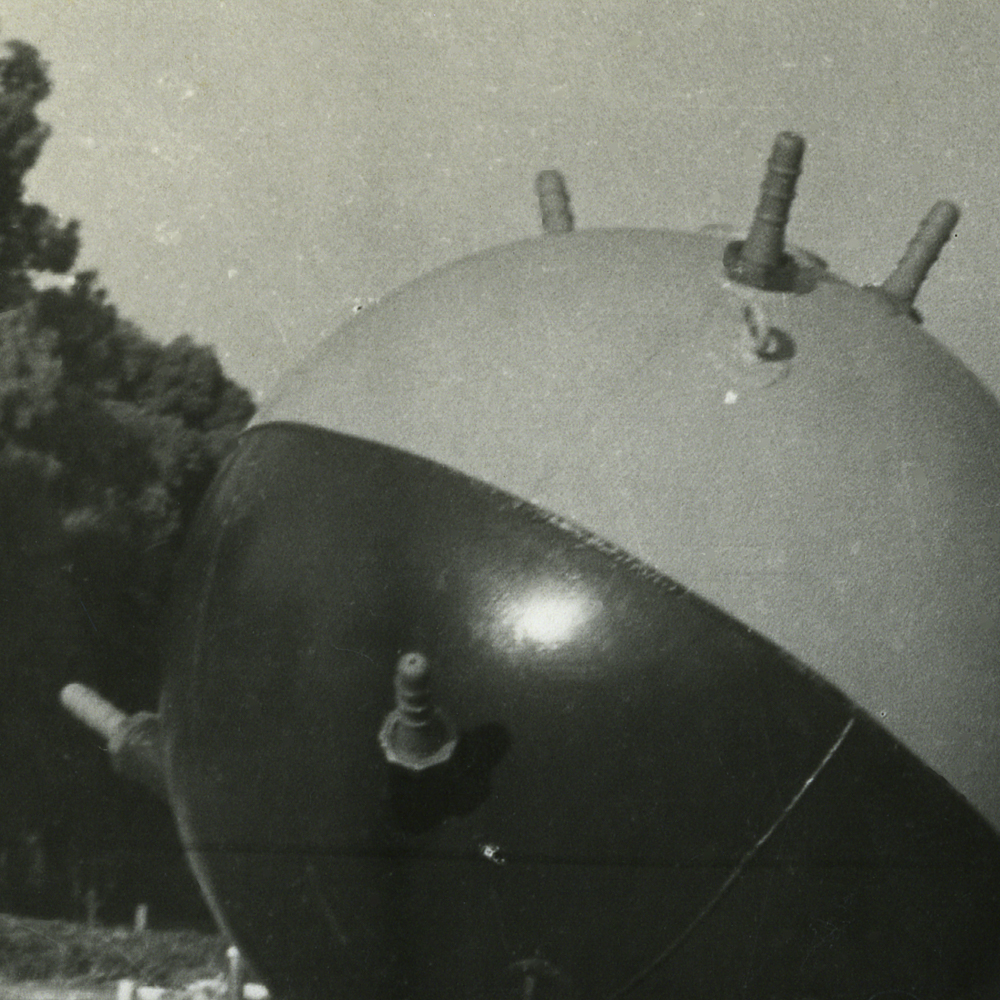

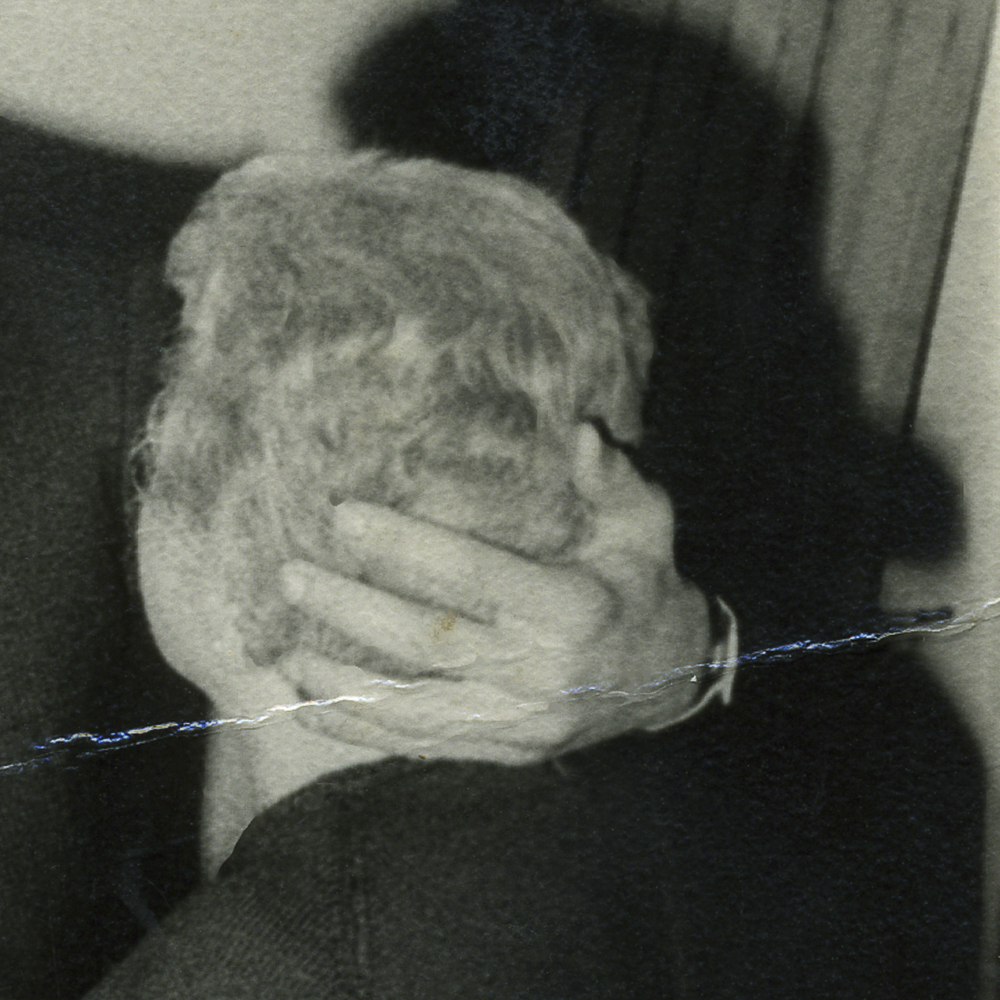

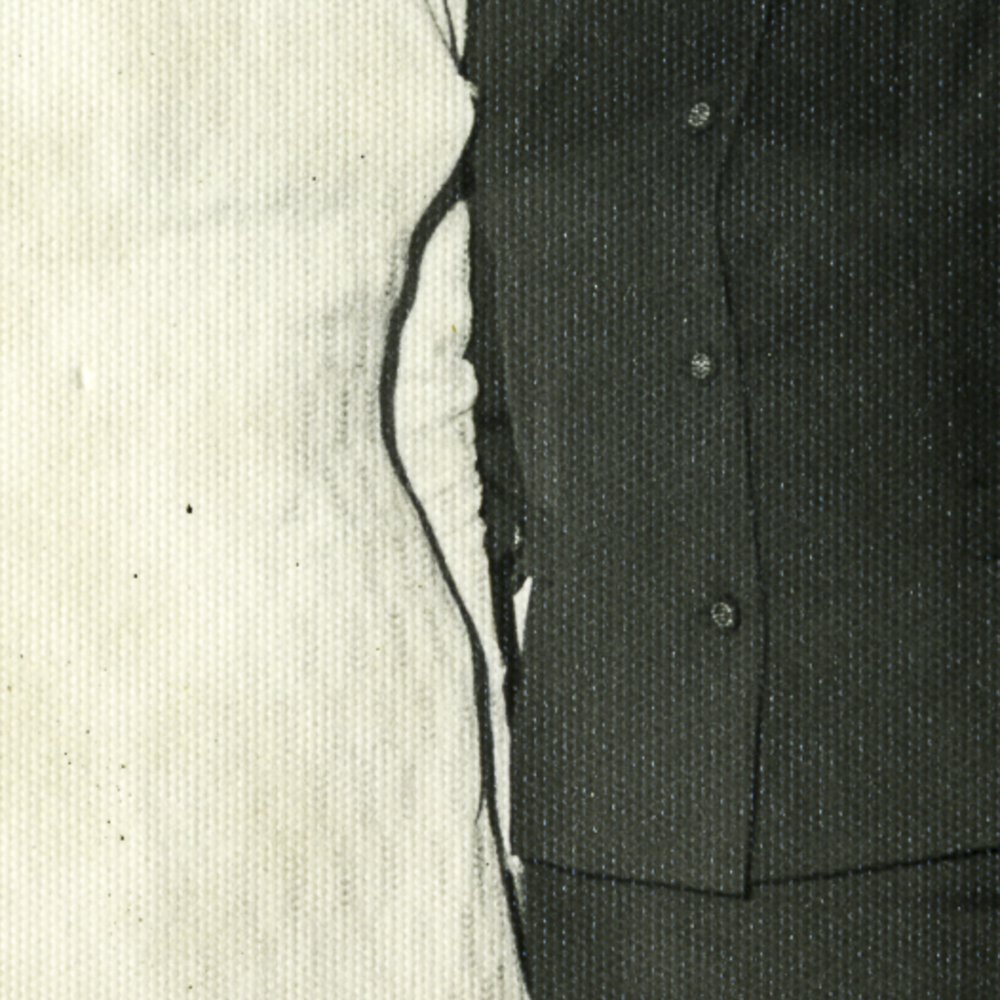

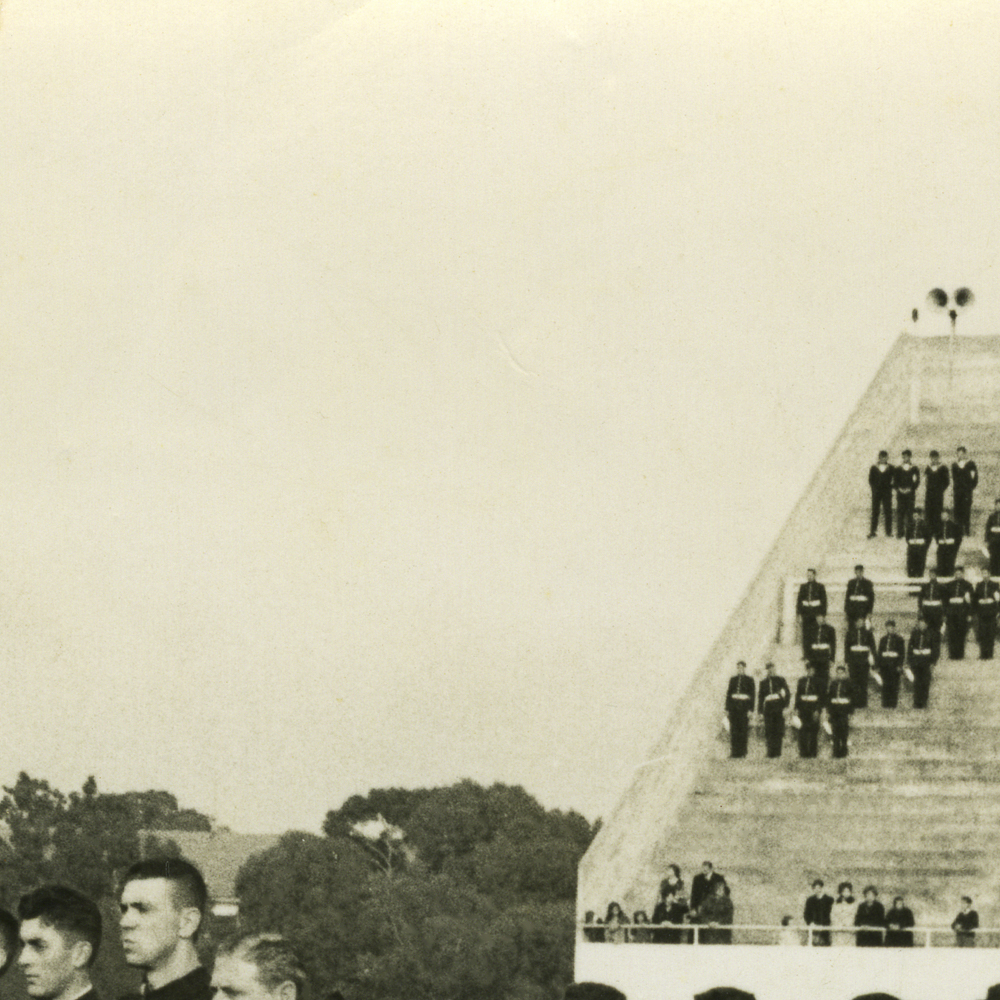

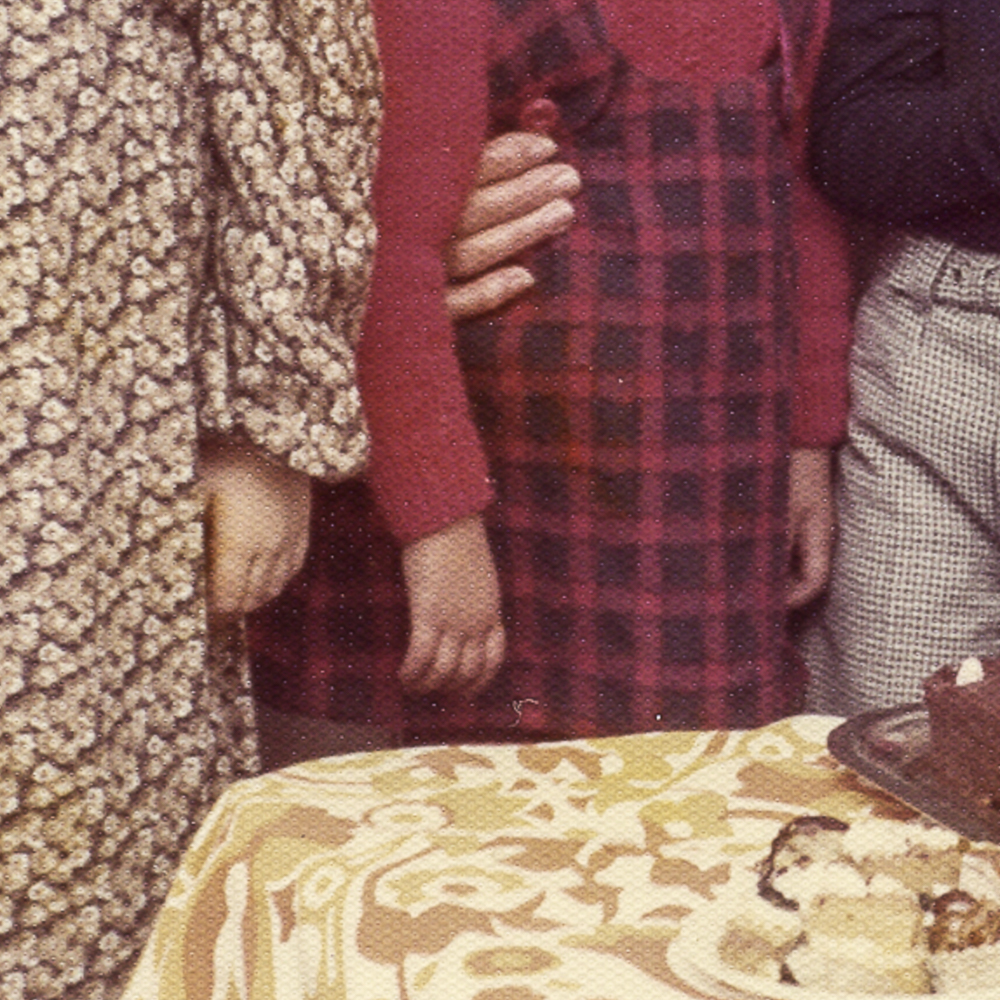

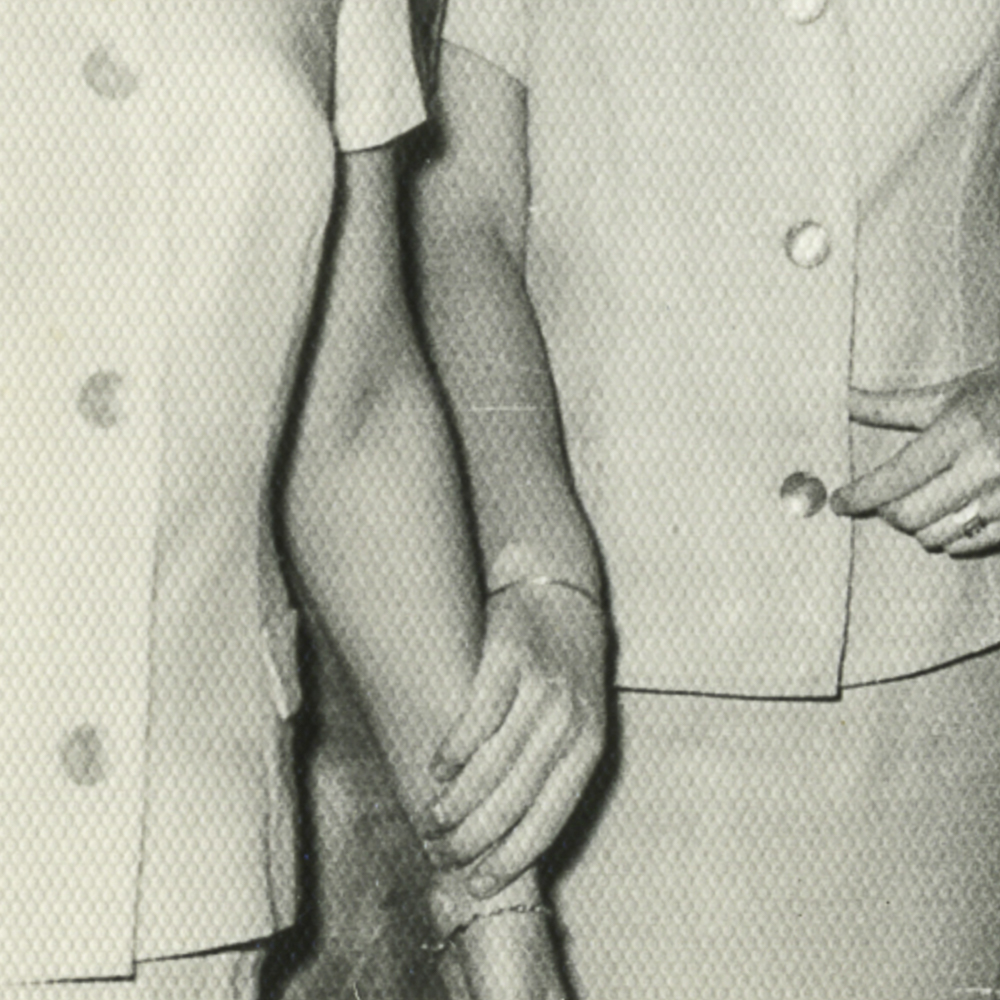

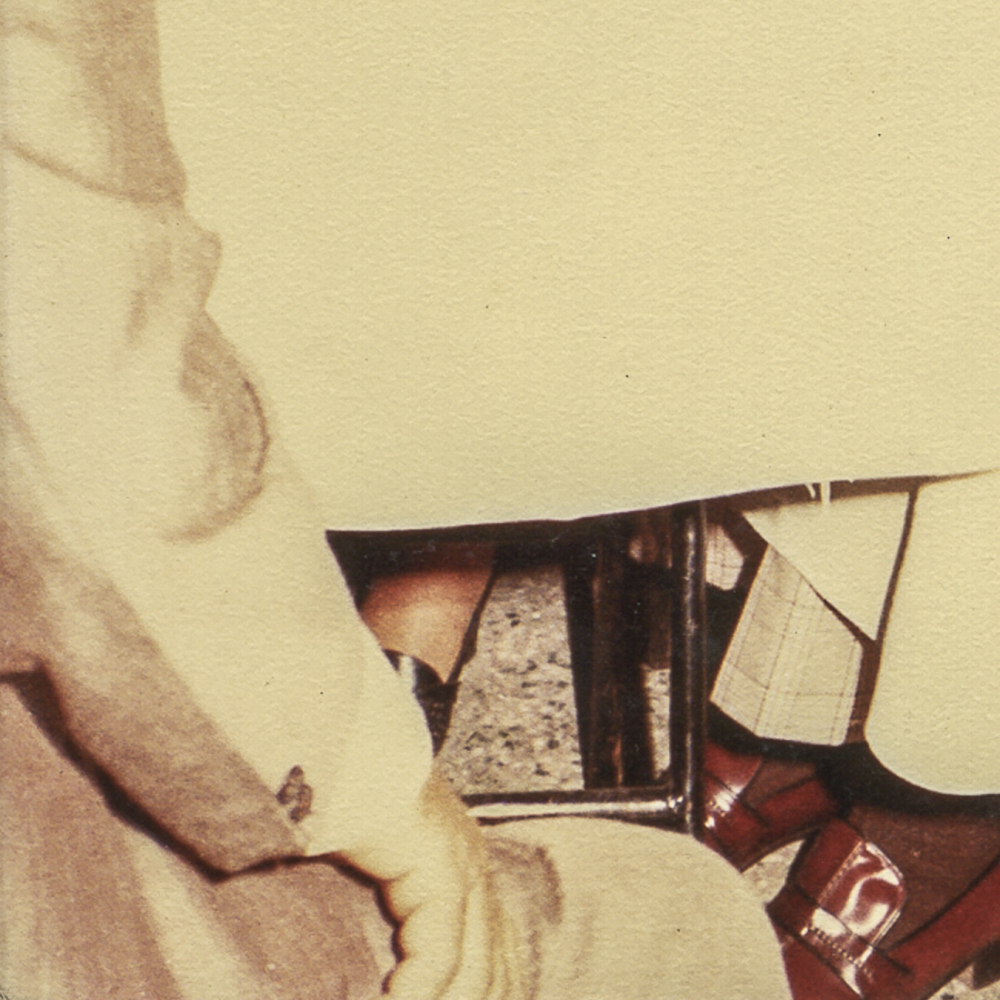

The fourth wall responds to the desire to explore the physical dimension of the photographic object to find some answers regarding the functioning of the family photographs as psychological territory: how do photographs mediate our family relationships? How do they intervene in our links in our understanding of family ties? Heeding to the mediation operated by the camera, the process has consisted of penetrate the image, immersing into it, to discover from there the opening to spaces reflection regarding both the family scope (in the gestaltic and relational senses) and the multiples temporalities of the image. In this sense, it points to another way of understanding the photographic event that goes beyond the shooting of the photographer (in the ontological sense suggested by Ariella Azoulay).

To photograph placing the camera “inside” the images, responds to the interest of altering the established order’s hierarchy regarding what supposedly gives it sense, and it also raises the possibility of attending to the blind spots of photography, that which usually escapes the gaze. To refine our gaze towards the seemingly secondary information produced by a picture, significantly dilutes the barrier which keeps us as external viewers.

If capturing has been considered for a long time as the essence of photography, the attention to archive has contributed to a new ontology of photography as a relational platform which doesn’t express the intentions of a solo participant. From this perspective, the reflection proposed by this project overtakes the family context and aims to a new comprehension of the photographic event, which surpasses the mere photographer’s capturing. It is in this sense that the fourth wall sets to overcome the understanding of the photographic act as a fait accompli.

In parallel, the anachronism that articulates this project is a way to visualize the multiple temporalities that every image carries, and the potential to upgrade the past, to invoke it and at the same time, reshape it in the present of who observes the image. In this way, the process I have engaged in reframing certain details of the image, has turned out to be a way of getting involved, of feeling part of my family history, rediscovering the imaginary potential within the photographic medium.

The fourth wall incites us to relate to the image in all its phenomenological dimension. This work is on affections and the mechanisms that raise subjectivity in photography, from which it invites the viewer to take a more participant and active role. Therefore, this project allows us to reflect about to what extent it is possible to expand the way we relate to the family album and, by extension, any image with which we are linked to.

Besides Azoulay, this project draws upon several sources, some of which can be highlighted as: Gilles Deleuze for his reflections revolving the image and multiple times, Jorge Luis Borges and his conjectures about time as unknowable phenomenon and protean reality, Michelangelo Antonioni in what concerns the peripheral gaze and Alejandro Jodorowsky in respect of his theories regarding family system’s healing.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Guest-Room Jörg Colberg«

»Der Greif #9«

Bibliography

Dec 06, 2016 - Diego Ballestrasse

In my last post I would like to present a bibliography referring to the topics raised in the previous posts, reference texts of which I adapted some fragments:

The multi-temporality of the image: On Borges and Interstellar

- Borges, J.L. (1996), Obras completas. 4 volúmenes. Emecé, Barcelona.

- Borges, J.L. (2014 [1944]), El Aleph, El Aleph. Barcelona: Debolsillo, 189-210.

- Hayles, N.K. (ed.) (1991), Chaos and Order. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago & London.

- Jaén, D.T. (1992), Borges’ Esoteric Library: Metaphysics to Metafiction. University Press of America, Maryland, Lanham.

- Kahn, C. H. (1979), The Art and Thought of Heraclitus. Cambridge U P, New York, Cambridge.

- Pérez, A.C. (1971), Realidad y suprarrealidad en los cuentos fantásticos de Borges. Ediciones Universal, Miami.

- Pineda Cachero, A. (2000), Literatura, Comunicación y Caos: Una lectura de Jorge Luis Borges (1ºParte).

Available at: javeriana.edu.co - Pineda Cachero, A. (2001), Literatura, Comunicación y Caos: Una lectura de Jorge Luis Borges (2ª parte) Política, Historia y Utopía.

Available at: javeriana.edu.co - Rojas Cocoma, C. (2012), Entre cristales y auras: el tiempo, la imagen y la historia, Revista Historia Crítica Nro.

48, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de los Andes.

Available at: historiacritica.uniandes.edu.co - Yudin, F. L. (1999), Variaciones Borges: revista del Centro de Estudios y Documentación Jorge Luis

Borges, ”Somos el río” Borges y Heráclito, ISSN 1396-0482, 258-271.

Available at: borges.pitt.edu

About the interstice in the Neorrealism:

- Deleuze, G. (1983), Cinéma I: L’image-mouvement. Les Éditions de Minuit, Paris.

- Deleuze, G. (1985), Cinéma II: L’image-temps. Les Éditions de Minuit, Paris.

- Deleuze, G. (2006), Conversaciones. Editorial Pre-Texto, Valencia.

- Durán Castro, M. (2003), Imagen, movimiento y tiempo.

PDF Available at: dialnet.unirioja.es - Cousins, M. (2001) The Story of Film: An Odyssey. Film Documentary.

Review: wikipedia - Kogonada (2013), What is neorealism?

Available at:bfi.org.uk - Massironi, G. (1997), Dear Antonioni.

Available at: IMDB

Ariella Azoulay and The Photography as a Collective Event:

- Azoulay, A. (2008). The Civil Contract of Photography. Zone Books, Nueva York.

- Azoulay, A. (2009). Alegaciones de emergencia: tres argumentos sobre la ontología de la fotografía, en Vicente, P. (ed.), Instantáneas de la fotografía. Arola Editors, 87-97, Tarragona.

- Azoulay, A. (2009), Act of State 1967-2007. A Photographic History of the Israeli Occupation, exhibition (Barcelona, June-October 2010).

Dossier available at: Dossier Antifotoperiodisme - Azoulay, A. (2010). What is a photograph? What is photography?, Philosophy of Photography, 1(1), 9-13.19.

Available at: ingentaconnect.com - Azoulay, A. (2011). Constituent Violence 1947-1950, exhibition (Tel Aviv, March-June 2009).

Available at: cargocollective.com - Azoulay, A. (2011). Constituent Violence 1947-1950, From Palestine to Israel: A Photographic Record of Destruction and State Formation, 1947-1950. Pluto Press, London.

Review: cargocollective.com - Azoulay, A. (2011), Archive, Political Concepts: Issue One.

Available at: politicalconcepts.org - Azoulay, A. (2012). Civil Imagination. A Political Ontology of Photography. Verso, New York.

- Barthes, R. (1989). La cámara lúcida. Paidós, Barcelona.

- Dahó, M. (2015), Fotografías en Cuanto Espacio Público, Revista de Estudis Globales y Arte Contemporáneo, Vol 3, Núm 1.

Available at: revistes.ub.edu - Heano, A. F., La Masacre De Las Bananeras Y La Ontología Política De La Fotografía De Juan Carlos Henao: Gabriel García Márquez Y Ariella Azoulay.

Available at: palabrasalmargen.com - Osborne, P. (2010), Alegaciones de emergencia: tres argumentos sobre la ontología de la fotografía, en Vicente, P. (ed.), Instantáneas de la fotografía. Arola Editors, 115-124, Tarragona.

- Valdés , A. (2015), ¿Quién Teme A Judith Butler?

Available at: elestadomental.com

The temporary alterations in the Expanded Cinema of Douglas Gordon:

- Badiou, A. (1999). El ser y el acontecimiento. Manantial, Buenos Aires.

- Bal, M. (2009). Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

- Bal, M. (2001). Looking In: The Art of Viewing. G & B Arts Internacional, Amsterdam.

- Biesenbach, K. (2007). Douglas Gordon, Timeline (Línea de tiempo).

Available at: malba.org.ar - Birnbaum, D. (2005). Chronology. Lukas & Steinberg, New York.

- Bourriaud, N. (1998). Estética relacional. Adriana Hidalgo editora, Buenos Aires.

- Conejo, J.F. (2014), 24 Hour Psycho, de Douglas Gordon.

Available at: revistacodigo.com - Fernández Pan, S. (2012), En busca del espectador emancipado Rancière.

Available at: esnorquel.es - Galerie Eva Presenhuber (2009), Press Release, Douglas Gordon at Eva Presenhuber.

Available at: contemporaryartdaily.com - Gordon, D. (1993), 24 Hour Psycho Sleepover, video installation 24h at Modern Art Oxford (Oxford, February 2016).

Excerpt available at: YouTube

- Lipovetsky, G. & Charles, S. (2006). Los tiempos hipermodernos. Anagrama, Barcelona.

- Mondloch, K. (2010). Screens: Viewing Media Instalation Art. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- Morrison, E. (1996), 24 Hour Psycho’ Douglas Gordon Documentary, Tv Documentary.

Available at: YouTube

- Osborne, P. (2010). El arte más allá de la Estética. Cendeac, Murcia.

- Rancière, J. (2005). Sobre políticas estéticas. MACBA / UAB, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona.

- Rancière, J. (2010), El espectador emancipado. Ellago Ediciones, Castellón.

- Segura-Cabañero, J. (2012), Temporalidades críticas: el caso de Douglas Gordon, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia.

Available at: Universidad de Murcia, Murcia. - Vice Magazine, Designing Video Installations with Douglas Gordon. Tv Documentary.

Available at: YouTube

Douglas Gordon’s temporary alterations on 24 Hour Psycho

Dec 04, 2016 - Diego Ballestrasse

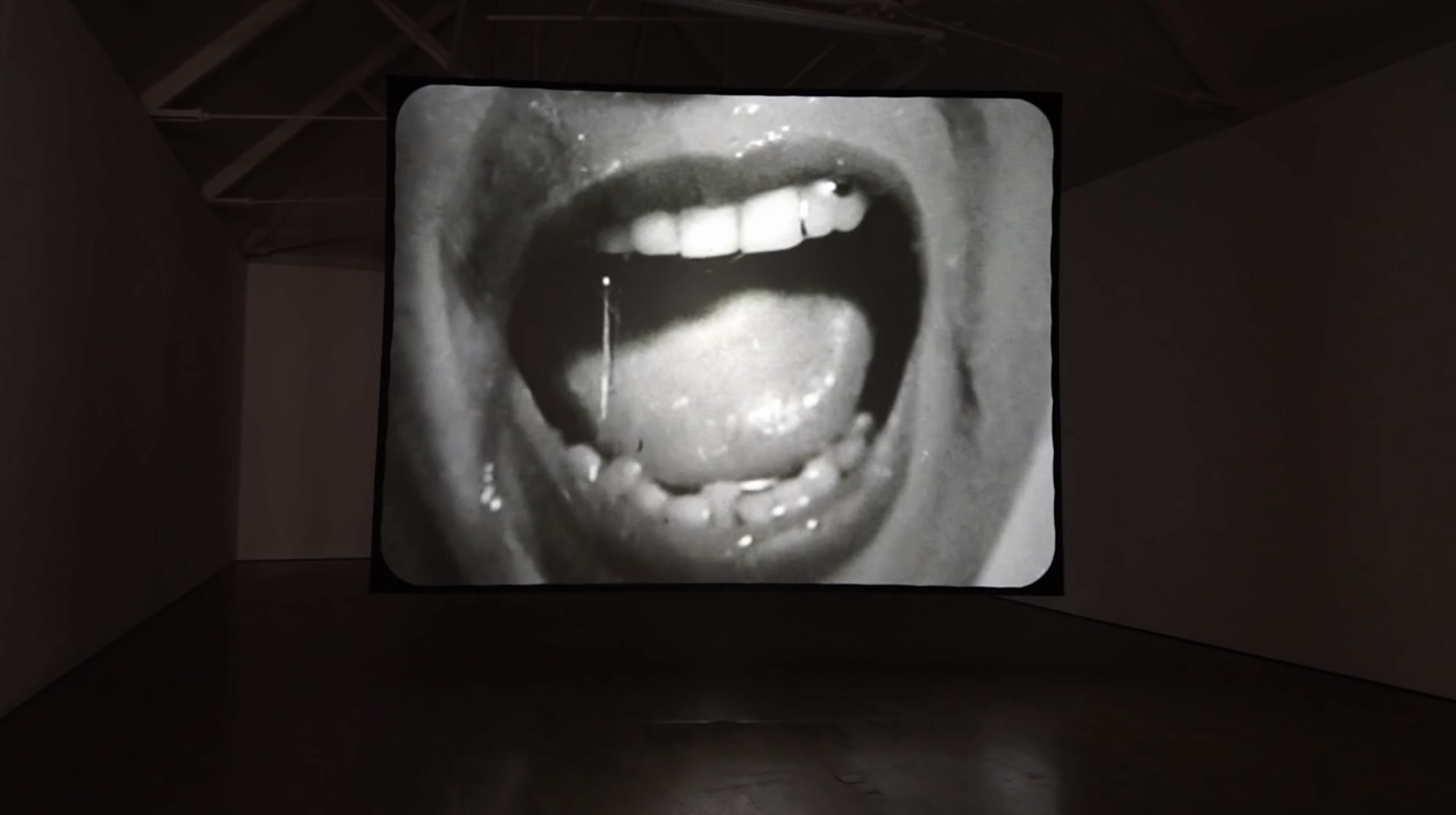

In this fourth post I propose an approach to Douglas Gordon´s work 24 Hour Psycho (1993), handled from the aspects I have been speaking of in previous posts: time and space.

The “Expanded Cinema” describes everything that goes beyond the usual technologies of film production and projection, it breaks the literary and static narrative of the unique image of cinema and incorporates visual resources that expand and question exhibition spaces and montage and distribution techniques(1).

The Scottish artist takes Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), slows down its original duration by extending it to 24 hours, projecting it in two frames per second and taking away its sound:

24 Hour Psycho , Video installation 24h at Modern Art Oxford (Oxford, February 2016). Excerpt:

This apparently simple process reveals a complex mechanism of memory in the viewer, producing a visual and temporal anachronism that allows a void of meaning in the work , and in the symbolic charge contained in it.

When lengthening the scenes, Gordon’s intention with this temporary alteration, is to remove the immediate tension that occurs in them, that is, to take the drama out of the film. An inversion is produced, a symbolic void that modifies the viewer’s way of seeing and thinking. Therefore, it changes around the reception and intensity of what is perceived.

Douglas Gordon appropriates Psycho by manipulating the visual perception of the film by means of temporal resources applied to the projection (scale and space disposition). By altering the temporal structure of the film, he passes off all production of meaning to the viewer’s subjectivity. Now, the problem for the viewer is what he sees in the image, not what will be seen in the following image. Likewise, objects and means no longer have a reality of their own but they acquire autonomy, material value by themselves. The separation between the subjective and the objective is weakened by the replacement of the optical situation by the motor situation. There is an indeterminable, more lax game, focused on daydreaming which generates a kind of oniric relationship, in which the released senses can establish their own relationships. In this operation the viewer leaves the interpreter figure and takes possession of a significant number of images to construct its own translation; what Jacques Rancière has called “emancipated spectator”.

Photography as a collective event

Dec 03, 2016 - Diego Ballestrasse

“Violence is not seen, there are no corpses”. This quote, said in Tel Aviv, was attributed by Ariella Azoulay to a historian, visiting her photography exhibition Constituent Violence 1947-1950.

Ariella Azoulay (Tel Aviv, 1962) teaches visual theory and is the author of several books, among which The Civil Contract of Photography (2008). In this essay, Azoulay has coined the idea of a citizenship of the photography, concept that is structured under the expository format in Constituent Violence 1947- 1950 (2011) and Act of State 1967-2007 (2009).

For Azoulay, the photography’s interest is in the archive. Azoulay compiles image files from various sources, these files -unfinished, open and susceptible to be enlarged- cover forty years of Israeli occupation.

Through the reaction “Violence is not seen, there are no corpses”, mentioned at the beginning, Azoulay points out several commonly held ideas on three themes: violence, photography and Palestine catastrophe. For Azoulay, these three assumptions are connected by the fear of those who show interest in the Palestinian catastrophe; a fear that, in the way it is presented in her exhibitions, is not shocking enough to make the viewer understand the depth of the Palestine catastrophe.

In the occupied territories, Palestinians can not express themselves publicly, and their private sphere is continuously sabotaged (searches, detentions, recordings). Azoulay does not search for images of attacks, but those of concordance. The file documents that those disputes were verbal, in assemblies, markets. Modes of proximity, on daily basis, that were not so contaminated by the violence, even if they were asymmetrical and conflicting. Therefore, it can not be made into a great success, or matter for news. The images of her archive, always accompanied by a legend, far from showing a great event, are intended to record a face to face experience between the photographer and the photographed. This face to face instance is especially significant because, according to Azoulay, for those who lack a State, photography plays a key role as a refuge, the only redoubt where they can still exercise their citizenship.

Azoulay notices a gap between the consideration of ‘this was there’ and the ‘this is X’, traditional photography argument, in such a way that the political relationship that photography provokes shows that “what was ‘there’ was not necessarily there in that way” (Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography, 94). This is what Azoulay calls the civil contract of photography and which consists of assuming the responsibility for reopening the political content that the fixing of the referent intends to eliminate. The viewer of the photography, sensitive to the gap, has the responsibility to reconstruct the event of photography and to re-signify what happens in it through the use of imagination (Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography, 14).

In this sense, Azoulay’s reevaluation raises an understanding of photography in terms of collective meeting. A meeting in which not only the photographer and the portrayed participate, but, in fact, an infinite number of people: those who were present at the time of the shooting, even if they do not appear in the image, as well as those that will later be part of this photographic event, expanded by viewing the image, or when they get to know about it through the story of third parties, taking into account, of course, that not all who participate in a photographic event do so in the same way, nor would access the photographic result produced, nor have the same right to use it, or to spread it (1).

In The Fourth Wall, I approach these mechanisms that enhance the subjectivity that all photography entails. Finding myself with the photographs of my own family file has been a continuation of photographic events that occurred in the past. This experience has become a stratagem to approach my past and revisit my own story, after which I feel more involved and active.

(1) -Dahó, M. (2015), Fotografías en Cuanto Espacio Público, Revista de Estudis Globales y Arte Contemporáneo, Vol 3, Núm 1. Available at: Revistes.ub.edu

About the interstice

Dec 02, 2016 - Diego Ballestrasse

In the decade from 1950 to 1960, the irruption of Italian Neorealism entails a significant turning point in the way space and time are treated in cinema, affecting the plot.

Gilles Deleuze has explained how, until that moment, the cinema is governed under the idea of the image-movement, analyzed on his study of cinema Cinéma I: L’image-mouvement (1983).This happens in such a way that the image in cinematographic movement obeys to the need to capture and reproduce actions that are organized in sequences of causes and effects: each image acts on others and reacts to others in a whole that integrates them: the script.

In that sense, Deleuze criticizes the image-movement considering it as a primitive cinema, developed basically within the stimulus and response scheme that governs its characters and the sequences of actions of their scripts. According to Deleuze, this type of film only stimulates the nervous system of its spectators at one sensory-motor level: its cerebellum, in which it produces laughter, sweat and tears. On the other hand, he argues that only by avoiding the scripts of films can the spectator fully contemplate their images, thus turning an experience conducted by a narrative function into a fully visual experience.

The difference between these two possible functions of the cinematographic image is also a difference of perception, especially of the spectator’s experience in relation to time. This is the case concerning the “dead time” in the films of Michelangelo Antonioni or Vitorio De Sica, in which there are images that do not lead to actions or are not explicitly relevant to the development of the script, analyzed in Cinéma II: L’image-temps (1985). This kind of drift from the script is kept for the treatment of time (the time that a scene lasts), as well as the space shown in the scene.

The Italian Neorealism incorporates elements that are usually “disposable” for the classic Hollywood directors. They occur when the protagonists leave the space but their camera does not follow them, nor the action is cut, the camera keeps shooting in the same space after the protagonist left empty, to stay with others who stayed or are about to enter. This way, the takes are maintained and diverted to include others; these “intermediate moments” seem to be essential, the time and space seem richer than the plot or the story.

In these terms, Kogonada defines the essence of Neorealism in this video-essay:

These “intermediate moments” that refer to the temporality of the image on the screen, we could also call “temporary interstices”, based on the passage of time during the scene. However, what happens to what is shown on the screen?

In that sense, Michelangelo Antonioni’s cinema uses unconventional and excessive framings, where his characters appear on one side or half hidden. Antonioni had studied USA abstract painting. His films looked like canvases of modern life in which people partially appear and his vision of empty spaces is related to a peripheral look. In his cinema, Antonioni explores and deepens the concept of emptiness as well as its visibility. According to John Berger, the Italian director’s interest “is always next to the event

shown”, in the words of Roland Barthes, “The artist stops and takes long looks, looks at things radically, until their exhaustion.”

In the famous ending of The Eclipse, Monica Vitti’s character leaves the film and never appears again. Instead, we see places, street corners where we had seen her with Alain Delon. Emptiness seizes everything. The world seems empty. As if all were dead or at home. We see this woman and we think that Vitti is back. But no, it is another restless passerby:

In The Fourth Wall, I explore this “space interstice” attending to the blind spots of photography, those which usually escape the eye. This device that allows me to photograph by placing the camera “within” the images, is not a simple frame within another frame: it is a subterfuge to alter the hierarchy of the established order within the image with regard to what is supposed to establish the meaning. It is a displacement of the attention of the gaze that goes from the explicit to the implicit, from what could be obvious to what is ambiguous, to discover spaces that do not lead to actions or not are explicitly relevant to the understanding or development of the argument proposed by the image.

As a consequence, images from the family archive are “born” like fractals, images that were inside the original image. Through this process, I go through the two-dimensional image at the same time as this is transformed into a deep space, in a three-dimensional scenario.

For all this, this project allows us to reflect to what extent it is possible to expand the way in which we relate to the family album and, by extension, to any image we feel linked to.

On image and time: a gear of different temporalities

Dec 01, 2016 - Diego Ballestrasse

Hello from Barcelona, in my first post I want to tell you about a literary and cinematographic reference which influenced me during the development of my work, The Fourth Wall.

During the initial phase of The Fourth Wall, the research process, I noticed the multiple studies on time and space covered from different points of view, among which I highlight Jorge Luis Borges’s. At different points in his literary work, Borges tackles the study of convergent times and the rupture of temporal linearity; he approaches these ideas in “The Babel’s Library “ (1941) and in “The Aleph” (1945).

Borges’s star is found in multiple films, as is the case of Interstellar (Christopher Nolan, 2014). On the end of the film, in the sequence of the hypercube in which Cooper is trapped, and is allowed to physically communicate over time using gravity, the library that Borges imagined is represented.

The scene shows Cooper trying to talk to his daughter from behind the shelves of her home library, an infinite library multiplied by each one of the moments of history:

This idea of fusion of time and space, also appears in the short story, The Aleph (1944), in which Borges describes a point in space where all the other points of space-time coexist, a point in the space that contains the entire universe:

“El diámetro del Aleph sería de dos o tres centímetros, pero el espacio cósmico estaba ahí, sin disminución de tamaño. Cada cosa (la luna del espejo, digamos) era infinitas cosas, porque yo claramente la veía desde todos los puntos del universo.”

“The Aleph’s diameter was probably little more than an inch, but all space was there, actual and undiminished. Each thing (a mirror’s face, let us say) was infinite things, since I distinctly saw it from every angle of the universe”

In this sense, we can say that the relationship between image and time is a gear of different temporalities. The image, every image, is, in essence, a multiplicity of times and, in turn, a “form” that is frequently updated, which renews processes of the past, which “crystallizes time” but also allows the emergence of aspects of the past that are not relegated to their time of production.

In The Fourth Wall, I address the familiar photographic archive from the present as an intruder that submerges in other times. The work process has proved to be a way of getting involved and feeling part of the family history through the archive and the photography, thereby rediscovering the potential of the imaginary that allows the photographic medium.