Diego Ballestrasse

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

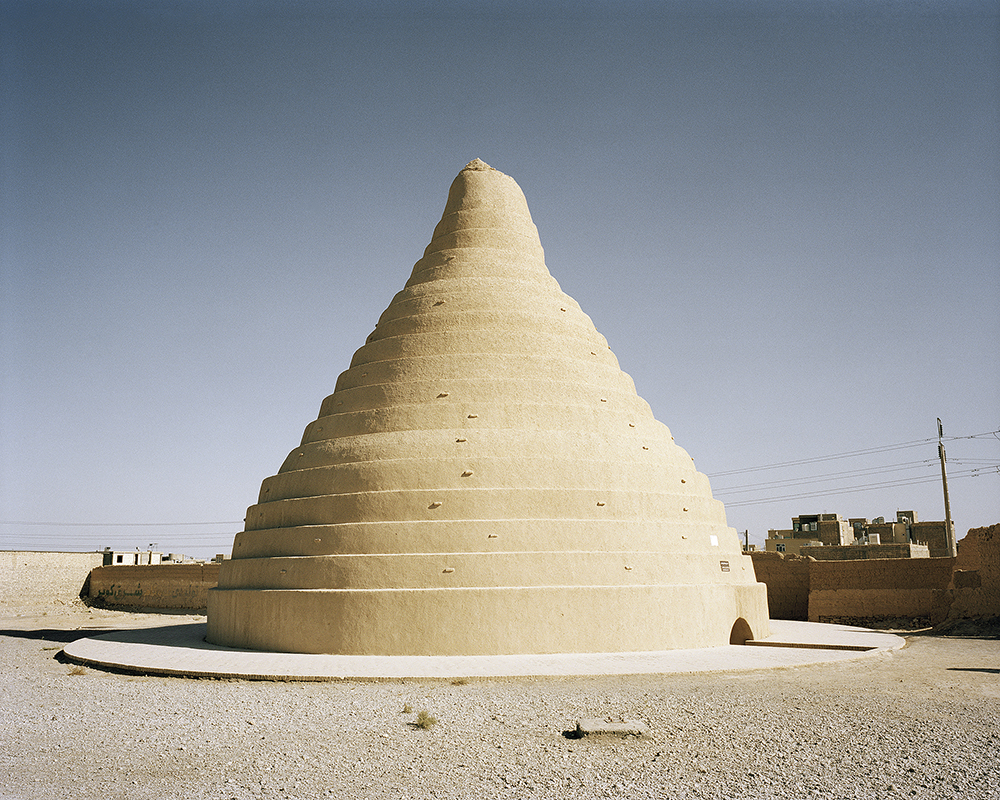

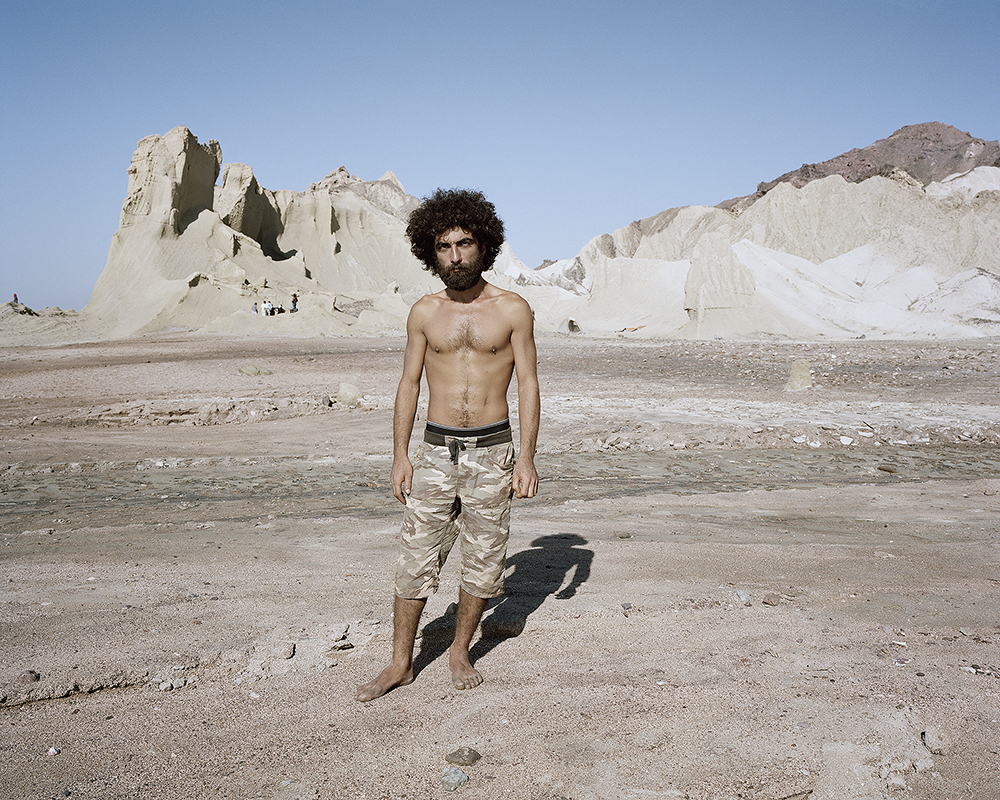

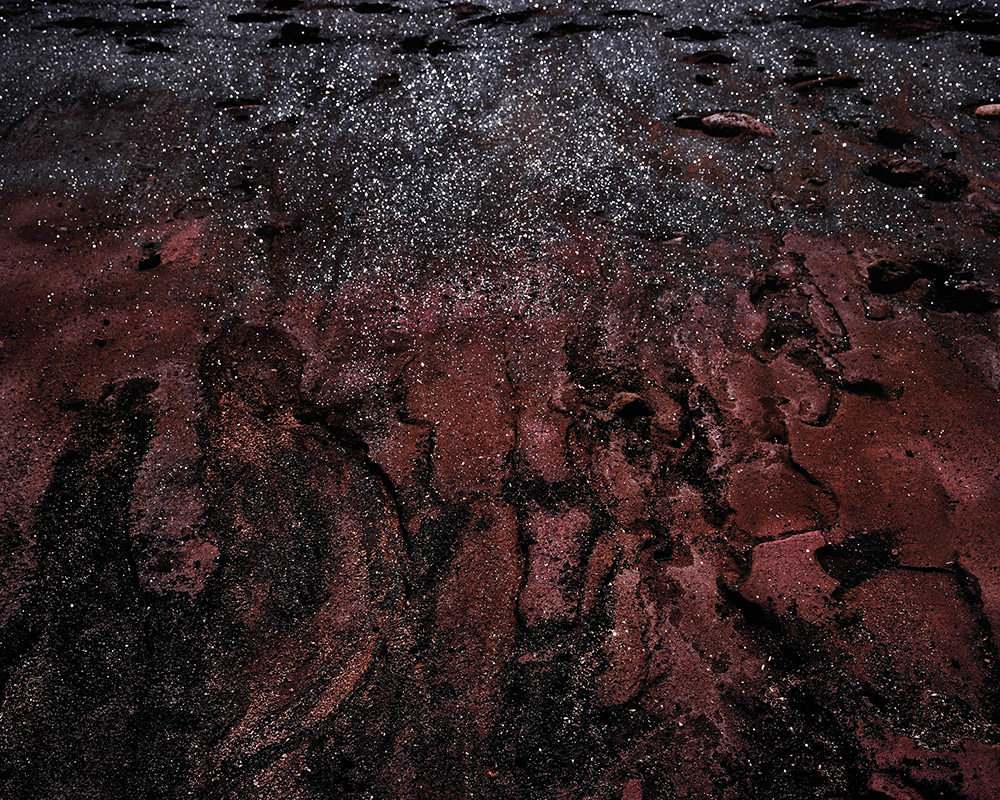

Hoda Afshar - In the Exodus, I love you more

Dec 07, 2016

This work is about Iran – my Iran – and my relationship to my homeland: a relationship that has been shaped by my having been away; by that distance that increases the nearness of all the things to which the memory clings, and which renders the familiar… strange, and veiled. It is an attempt to embrace that distance and to turn it into a kind of seeing. To let what is both there and not there shine through the surface. To let the surface speak. It is an attempt to explore the interplay of presence and absence in the history of Iran and in Iranians’ lives, and to discover the truth that lies there in their never-ending meeting, in-between.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Der Greif #9«

Max Pinckers – the world as stage of appearances

Dec 13, 2016 - Hoda Afshar

Reading Max Pinckers’ powerful and engaging images, and reading what others have written about them, I am interested not only in the similarities between our respective ways of seeing the surface and of constructing images, but also by the way in which our similar approaches – and our individual-but-overlapping intentions – are, or might be, easily mis-read; for like myself, Pinckers’ has elected in many of his documentary-narrative series to use ‘staged’ photography in order both to capture a side of reality (which has to do with the meaningfulness of the world for us as an image, and with re-presentations), and to interrogate the way in which reality itself – and not ‘merely’ our attempts to re-present it – is always bound up with the nature of reality as appearance and as appearing – with the world as the ‘stage’ of appearances – and with the plurality of viewpoints that make up our shared reality; but it is easy to misread this second concern (which in Pinckers’ series “The Fourth Wall”, “Will They Sing Like Raindrops…”, and so on, is partially explored through their ‘cinematic’ language) as a sort of secondary, and perhaps ‘merely’ aesthetic concern which is meant to point to the image’s (and these images’ in particular) blurring of the boundary between reality and fiction – to add an added layer of surreality which is supposed to mirror the fictionalization of lives and stories that we see projected in and through the cinema, newspapers, television screens and magazines (etc.), and which re-enter mediated ‘reality’ as real fictions when living-actors act out the roles they see played out in such scenes. But between these imaginative layers of Pinckers’ work – the back-and-forth play between real life and its captured images, and the self-interrogation of the photographic medium as implicated at one and the same time in mediating and in re-creating ‘reality’ – we can also read in Pinckers’ images (or this is how I read them anyway) a playful but serious concern with the self-selecting nature – the reality – of life as appearance; for the very nature of appearances suggests both what appears, and those beings to whom all ‘appearances’ appear, and on both sides there is always a ‘choice’ – conscious or mechanical – that determines both what is shown (or not shown), and what is seen (or unseen); and this is mirrored in both the actor’s choosing how to appear and in the audience’s choosing what to see – both of which are partially mediated by the circulation of representations (such as stereotypes) that precede us. So, speaking about his series “The Fourth Wall”, Pincker has noted: “The people in these images become actors by choosing their own roles, which they perform for the camera and its western operator”, while in “Two Kinds of Memory…”, Pincker gets ‘real’ Japanese actors to act out our own – “Westerners'” – projected fantasies about Japan, with the important foot-note, which Pincker gives, that these fantasies are in part as well the product of the country’s own projected self-image… None of this, however, can or should be reduced to a simple statement about life itself or its documentary or artistic images as being always situated between reality and fiction, for it speaks instead to the absolute coincidence of being and appearance: to the plurality of viewpoints or positions – situations – that mark the world-as-appearance (which again, is the only world we know) – a constellation of perspectives which, far from ‘resolving’ into nothing, pure fiction (as if the world just were those viewpoints themselves), we must struggle to navigate, and to judge, as both positioned and concerned spectators and actors.

Max Pinckers’ website: maxpinckers.be

(These reflections combine part of my doctoral research, which seeks to connect my own practice to wider theoretical concerns in in contemporary photography, art-making and cultural studies, and another ongoing conversation between myself and Timothy Johannessen, from whom I have benefited from discussions about the writings of Hannah Arendt and issues related to representation and reality in contemporary photography and cinema.)

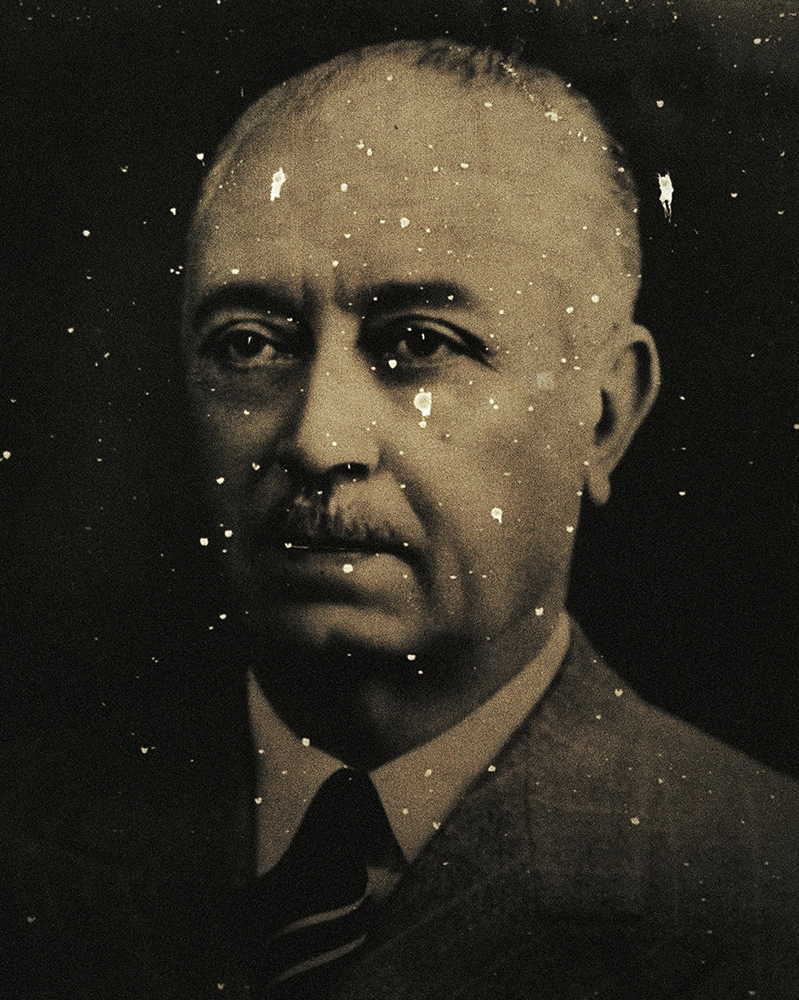

Broken Reflections / images of Iranian martyrs

Dec 12, 2016 - Hoda Afshar

Images of lives, made to be remembered. Evidence, traces, of a history that still lives. Of souls still living. In still images, and in the memories of a nation. Living, till no longer seen… In Iran, more than two decades later, faded, and fading still-photographic images of thousands of these men, martyrs – witnesses – of the Iran-Iraq war still adorn our streets, and grace our walls. They are everywhere. We remember them. And seeing them, we remember. Those of us who lived through that terrible war. But we remember them, and that time, in different ways. And these images— they mean for us, for each of us, different things. But they do mean for us – for all of us – and this is precisely their importance for me, thinking about these images as images, and as an Iranian; they are a metaphor – and more than a mere metaphor – that visibly and tangibly expresses the way in which the image-as-evidence expresses, and creates, a shared, while variously experienced history. A reality. They unite us, even while they divide us— those of us for whom these images carry a particular memory. They are part of our collective memory. And I cannot help but be struck by the way in which the ‘imagined’ community of a nation literally lives, and is born through such images; and too, by the way in which the frayed edges of these fading images express the fragility of life, and the fragility of our memories— their beautiful, but impossible resistance to death and to forgetting. But this truth – the truth of the image as evidence (of the opposition of life-and-death) – does it not lie precisely in what it conceals— in these images’ partial unreality for me? In the value of this truth precisely – and only – as a partial fiction? As a near, but still-in-some-way distant – removed – reality? Is this not the violence of every image, and metaphor— that it necessarily leaves something out in bearing meaning from one place to another, even if its meaning depends, anaphorically, on what came before? Is the truth of the image, as-metaphor, to be found in what remains, or in the remainder— in what has been carried over, or in what has been taken away? This is a very difficult thought. But for me, it is the very thought of the image, and of art. It is what we see in its images of life, and in its broken reflections; and it is what we see, albeit indirectly, in the image’s own way of teaching us to see. And this, in part, is what these images’ meaning is for me.

“Close-up”. Abbas Kiarostami

Dec 10, 2016 - Hoda Afshar

Abbas Kiarostami’s ‘Close-up’ (released in Iran in 1990) needs little introduction. This film not only introduced non-Iranian audiences to the new wave of Iranian cinema, and to a whole new world of film; it also revolutionized cinema outside of Iran (while at home, where the film was at first not well received, the recognition of its critical reception abroad encouraged Iranians to read their own new-wave of cinema in a new light—a fitting dialectic for this film). But apart from its needing little introduction, it is also a film that demands to be seen, and not written about, for its genius, or part of its genius, lies in the fact that what it communicates is communicated precisely in the reflective union of its form and content. Both must be, and can only properly be read and understood simultaneously. And this strange fact (whose strangeness, again, must be experienced to be understood) no doubt explains this film’s success as a film (which is to say, in terms of its realizing the pure possibilities that belong to this medium alone), and so too, its critical success. And so I should mention only a few essential things, including what is the film’s importance for me.

Kiarostami’s Close-up presents the true story of a fiction-drama—of a real-life man, Hossein Sabzian, who convinces a well-to-do family—the Ahankhahs—that he is the noted Iranian director, Mohsen Makhmalbaf. He offers to include them in his next film. But he is eventually discovered, arrested, and taken to prison. All of this really happened; and while Sabzian was still awaiting trial in Iran, the story was published in an Iranian newspaper. Mid-way through filming another production, Kiarostami learns of the case and hurriedly decides to get permission from Sabzian, the Ahankhahs, and the court to film the proceedings. He is successful, and the majority of the film is focused on the court-room trial, during which Sabzian humbly defends his actions, and is eventually pardoned by the Ahankhahs. But Kiarostami manages also to convince both parties, (as well as the journalist Farazmand who broke the story, and the officers present at Sabzian’s arrest) to fictionally re-enact the events leading up to the trial (and these scenes frame the real court scenes and provide the film’s narrative structure), and Kiarostami also ‘stages’ the movie’s dramatic finale: a passionate meeting between Sabzian and the real Makhmalbaf, who visit the Ahahnkhahs together in the beautiful closing scenes.

Part documentary, part dramatic reconstruction, the film inhabits these two levels simultaneously, and boundaries blur. There is the story—Sabzian’s-impersonating-Makhmalbaf—and then its reflexive telling, which increasingly becomes itself the subject of the film. Once Kiarostami’s partly-staged documentary enters the real world of Sabzian’s fiction—and the Ahahnkhah’s deception—both the story and the trial (whose course of events is increasingly determined by the film’s involvement) become a sort of alibi for the film’s interrogation of itself or film-in-general’s ability to capture truth without distorting it. And all this is communicated meta-filmically too. Almost everything in the film serves to distance the viewer in some way. We rarely truly get close-up to any character; or the closer we get the more things become distorted. In the re-enacted sequences, cars and objects come between the camera and the scene, or the camera dwells on seemingly unimportant details. The action is always at a distance. During the real court scenes (shot on grainy 16mm film) and in the film’s finale, equipment fails. Sound cuts out. We are made aware of the medium, as if to be reminded that neither staged-documentary nor recreated-reality are adequate to conveying, or discovering, unobstructed truth.

Close-up moves imperceptibly between these layers and by utilizing the pure poetry of Kiarostami’s cinematic language. But despite the constant presence of these themes (reality-as-fiction, art-imitating-life-imitating-art and so on) the film’s intent is not reducible to simple statement about the limits of film or any documentary medium to dis-cover truth, and to lay bare the mechanics of the ‘real’; what it interrogates, rather, is the at-once-beautiful, but tragic promise that cinema (like all art) offers by way of a sort of justification for life’s injustice and suffering. For the artist, no less than the executor of the law, has to choose; she has to stand somewhere, and her impartiality reflects nothing more nor less than her having some criterion, which she uses to determine what is essential and what is inessential, and what can be called upon as evidence. But it is not clear what art’s criterion, in promising some form of redemption, is. Sabzian, we learn, became obsessed with cinema because of the justification, the meaning, that it gave to his own anguish. But he ends up becoming its literal and figurative prisoner, just as the Ahahnkhahs are drawn into Sabzian’s world and ruse through their own obsession for cinema. And though the film manages to draw out a beautiful lesson from this, it is only through its own becoming perilously involved in that reality that it set out merely to represent, and not, as it were, to author.

* These reflections on Close-up are part of an ongoing conversation between myself and Timothy Johannessen (researcher-in-philosophy/artist). For each of us, this film has deeply influenced our vision and practice.

The image as evidence

Dec 09, 2016 - Hoda Afshar

The documentary image—By embracing its reality as a fiction, and by announcing its own presence (and not only what it re-presents: the pretended semblance to an unassembled reality) what it becomes is a sign. A sign that traces its own history, or quite simply: an evidence. This is, in part, how I see this series, which in a way both is and is not a documentary series, since what it attempts to explore, in stages, is the different ways that what is there to be seen, and what is not seen, reveals itself in different ways, in the light of our shared, and personal histories. And in the first place—and this is where I begin—what I am interested in is the surface. With the screen itself, or the stage. With what reveals (and not what is there, at first, revealed, but rather the place, the mirror, in which the world as image appears). But that where, the world as mirror, is itself for us an image, since it is always, and only made meaningful as an image. And again, what interests me is the way in which our understanding of it—of the world—precedes us, and exactly how its meaning and experience for us changes, including the experience of familiar worlds. As, for example, when we migrate—how that distance gives home, our image of home, the air of fiction. But there is a certain truth in this experience too—in the way that distance makes you see things. And really, this is what I’m trying to capture first of all in this series. This sense that leaving ruptures your connection to the place you’ve left behind so that, even when you return, it’s like you’re always waiting to arrive. That rupture is always there; and the way that the past and present, and the presence and absence of all those things that are (or were) both there and not there is felt, it conditions your whole experience. So about my making work about my homeland, Iran—my closeness and my own regard makes it impossible for me to tell what impersonal value my images might have—as reportage, say. But what is there to be seen represents only one side of what is, or can be evidenced. There is also our being there, our presence; and again, it is this that interests me first of all—the different ways that we construct our images of the world, of home, and so on. Different ways of seeing, and of making sense. The image as testimony. As true fiction.