Salvatore Vitale

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

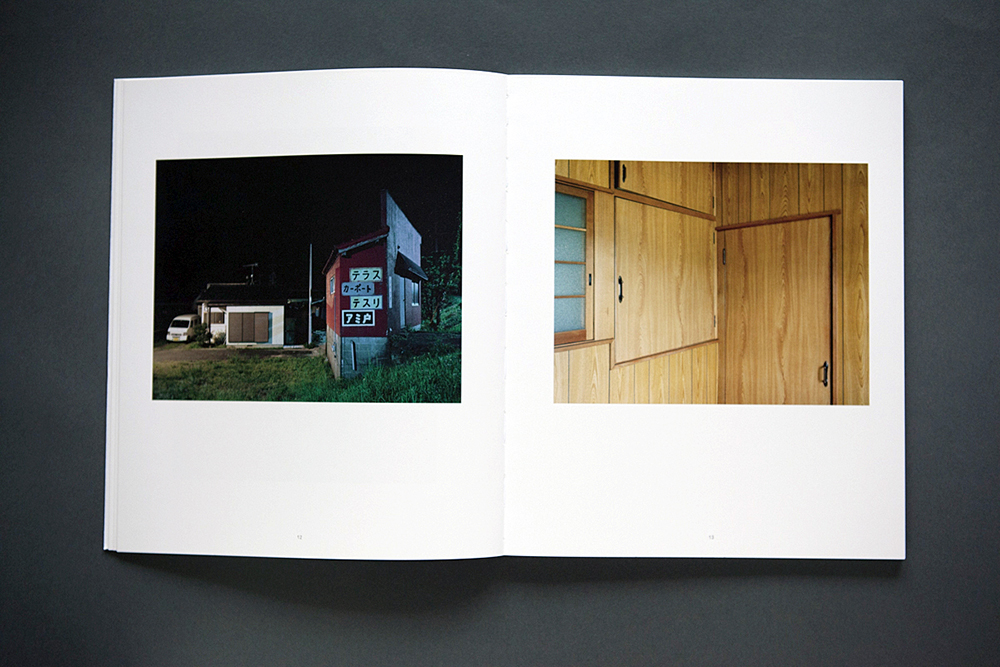

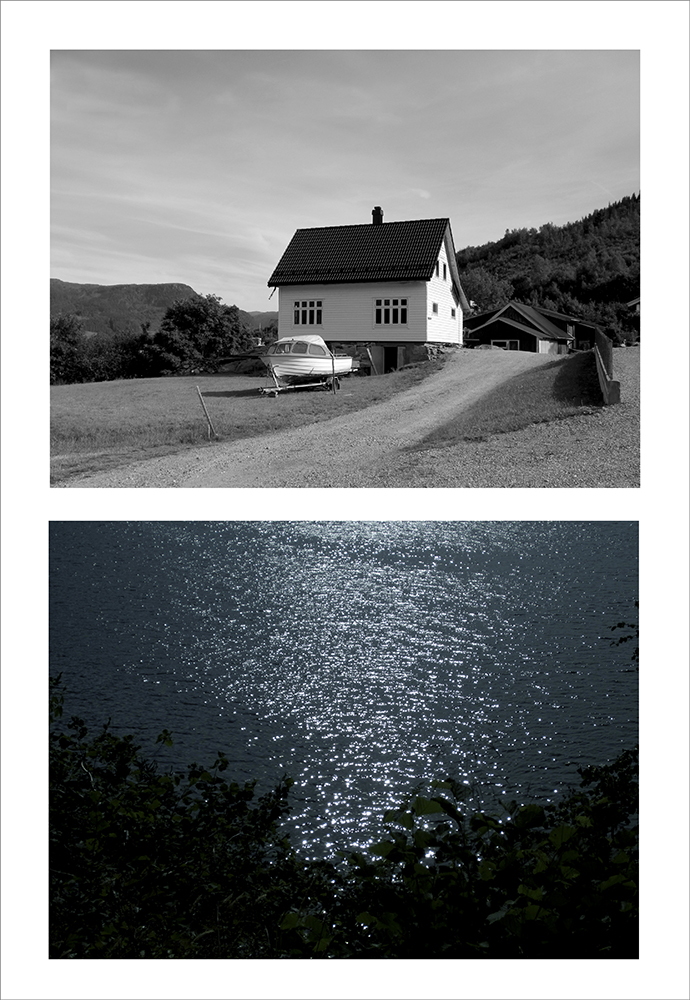

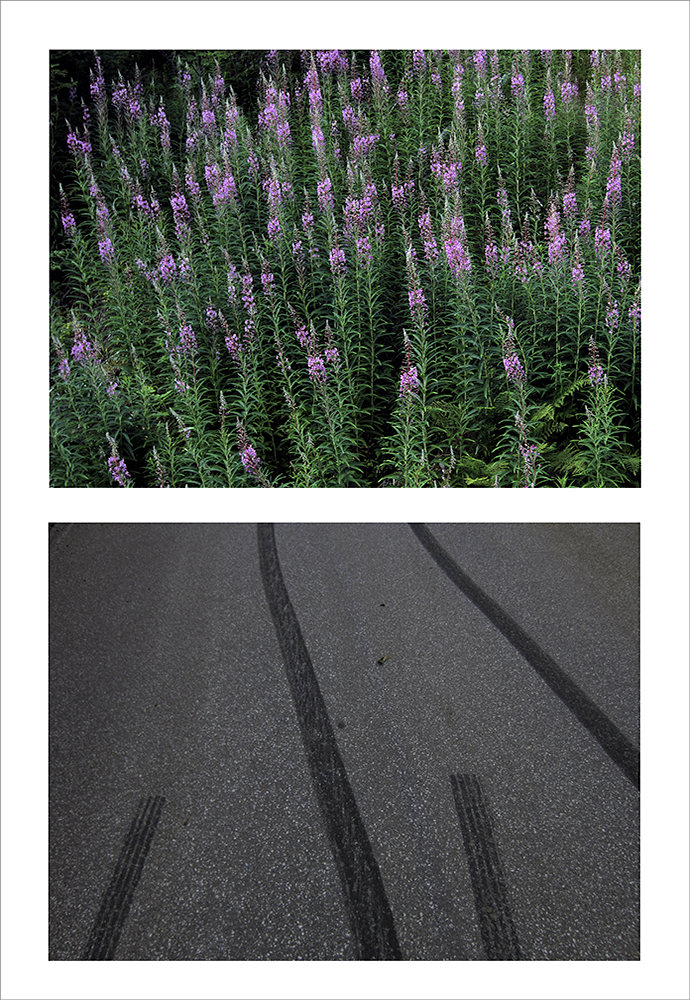

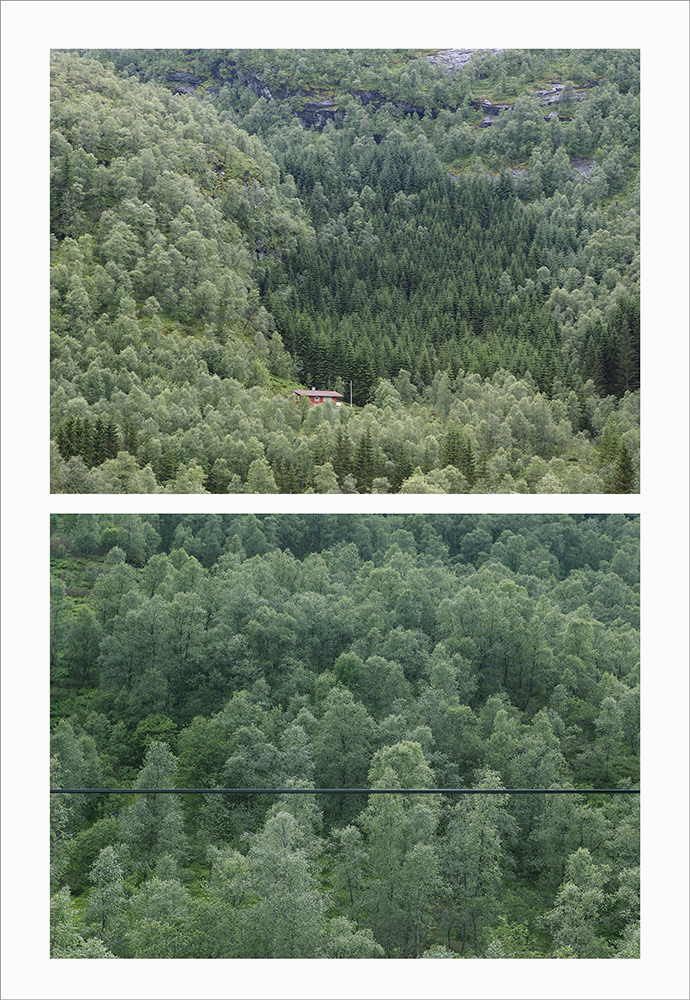

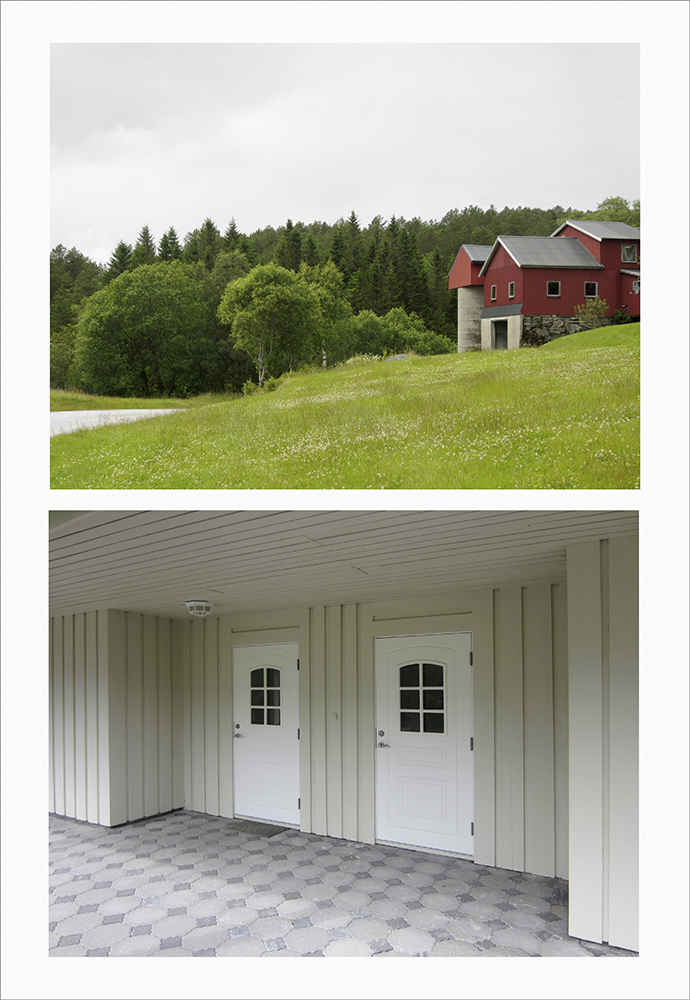

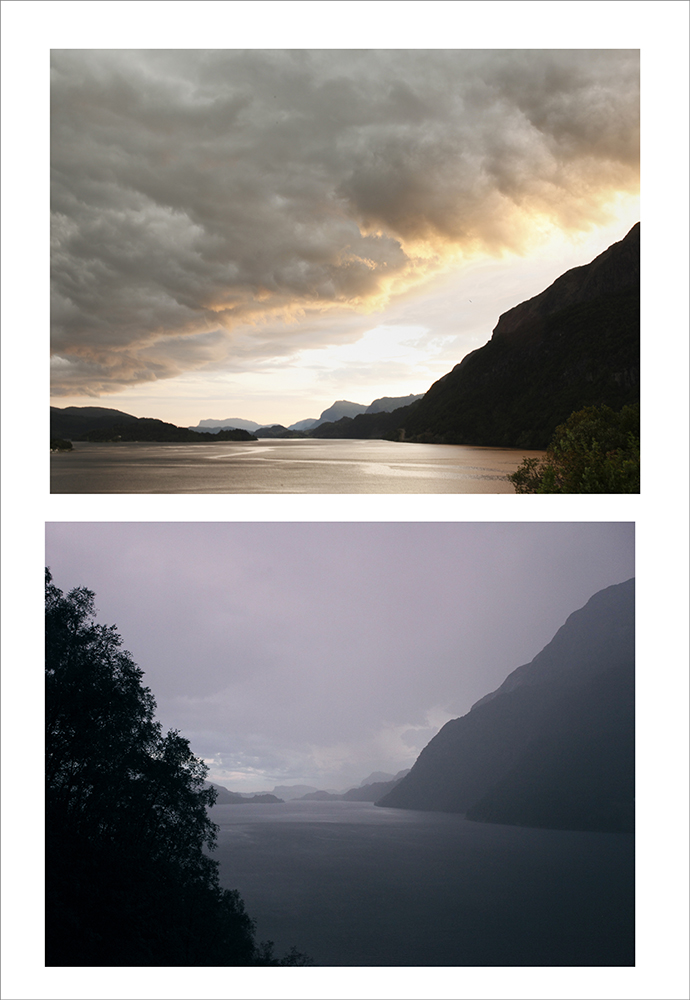

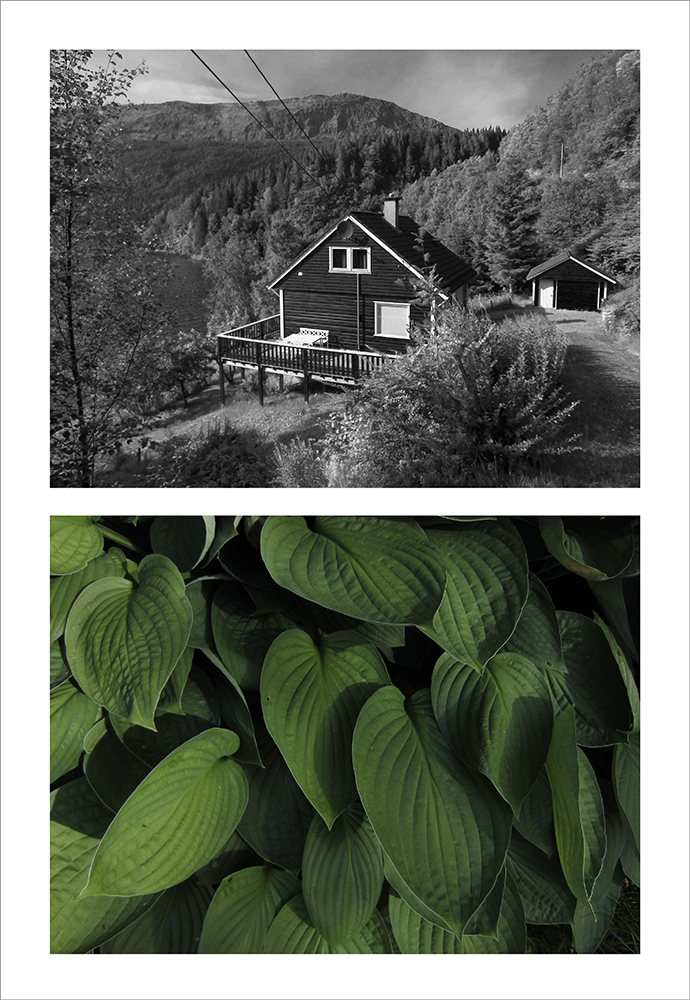

Juliane Eirich - Dale

Oct 14, 2015

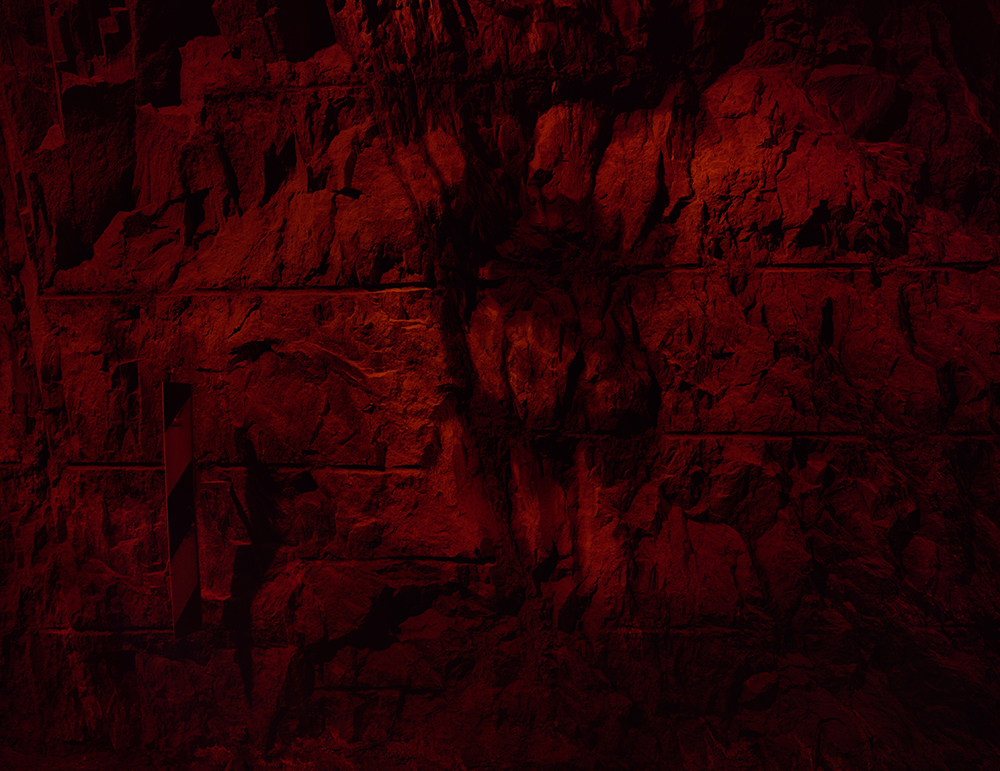

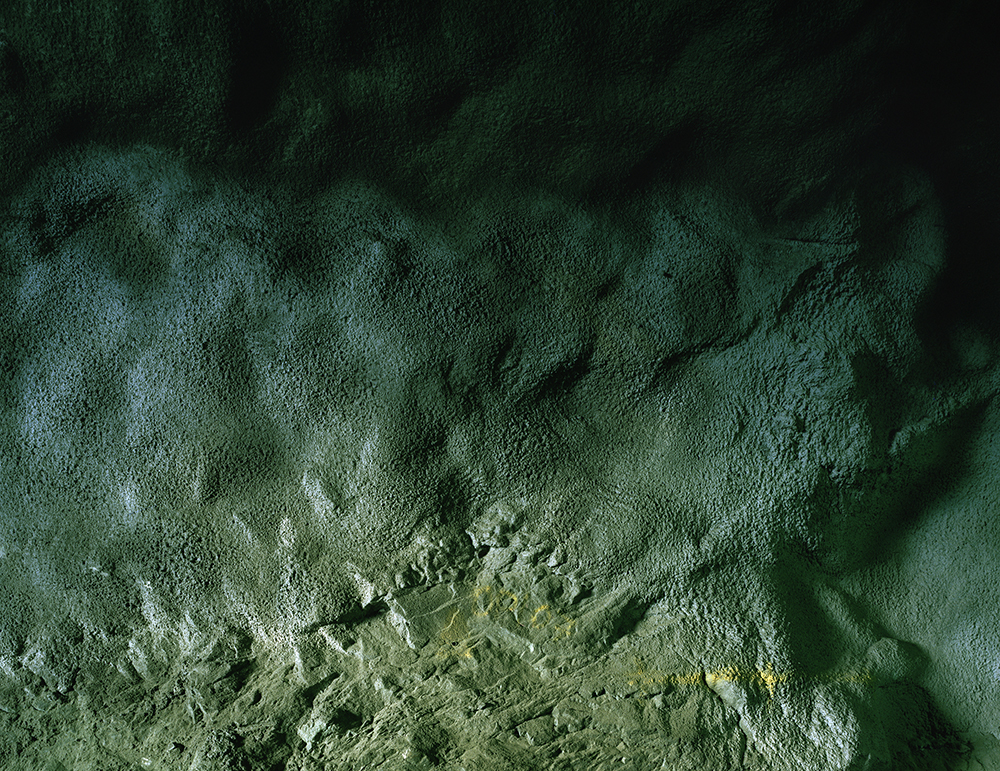

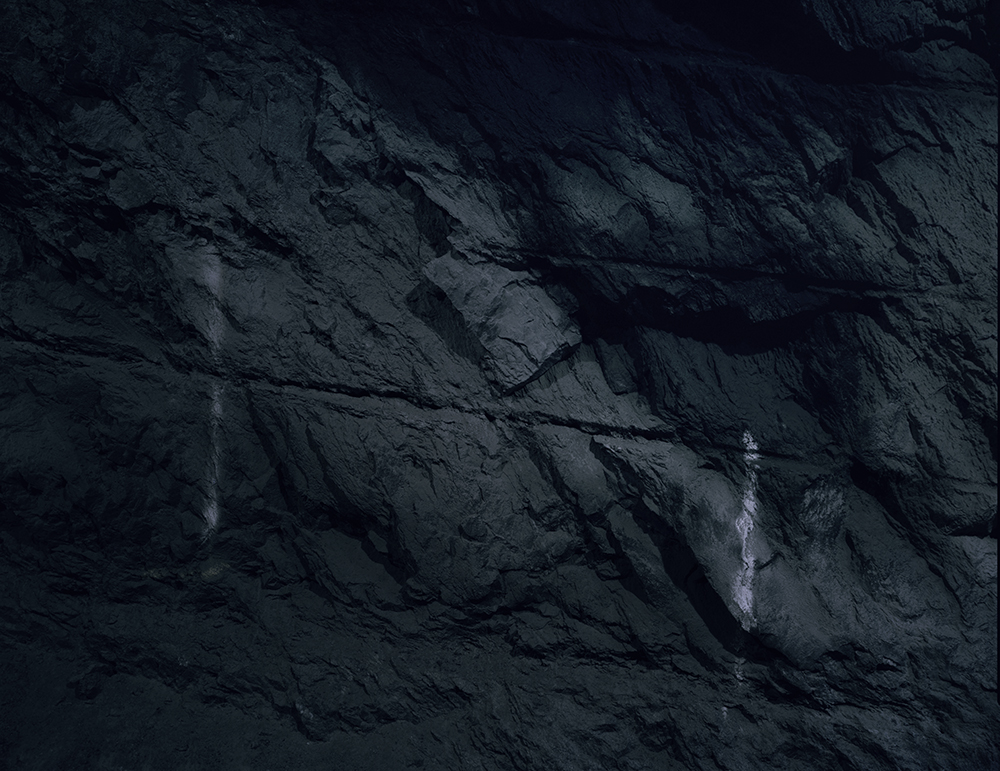

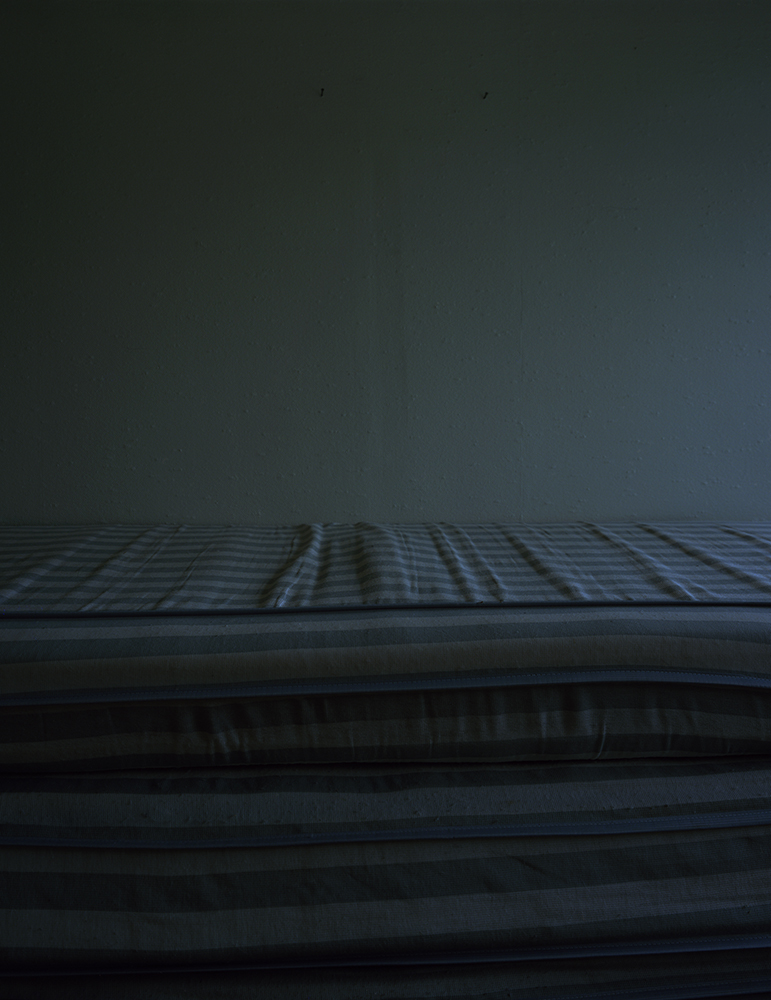

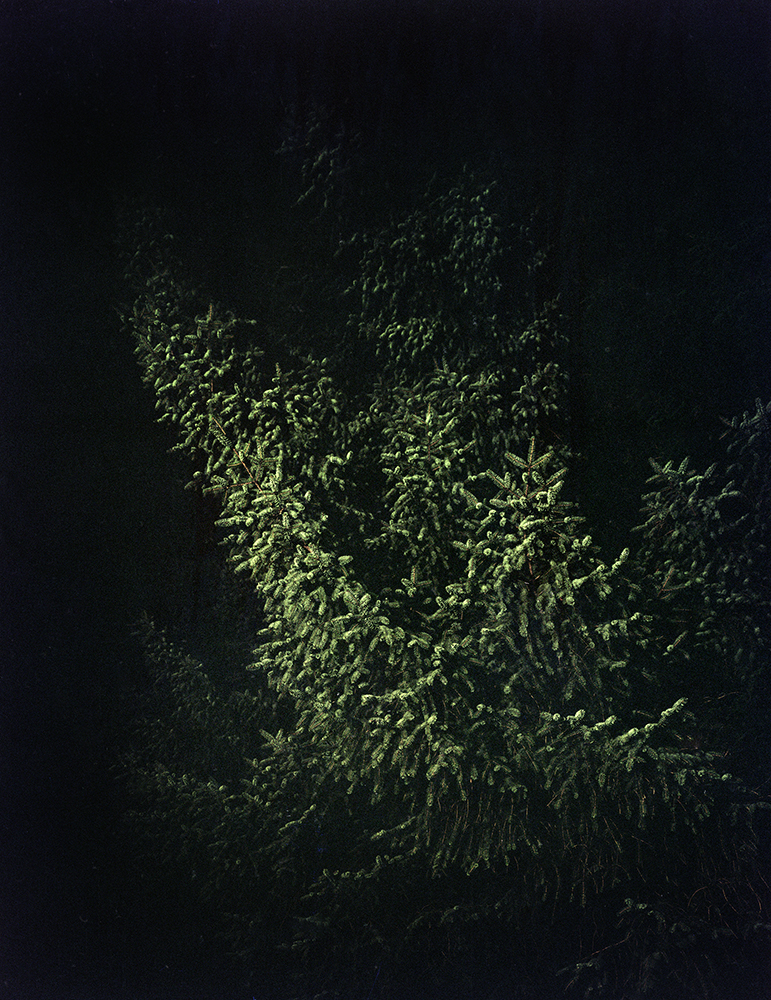

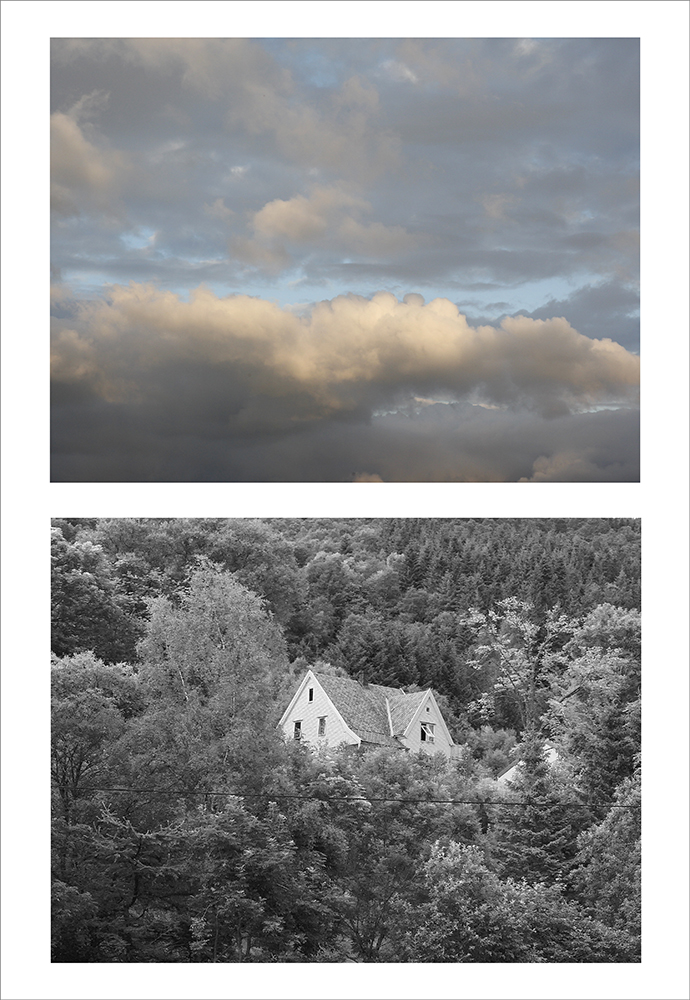

I photographed this series during a two-months artists in residency in Dale, Norway, in July and August 2014. My main interest in photography is the relation between man-made environment and nature. I am exploring how both influence the other in terms of culture/cultivation and social aspects. In my eyes it is both fascinating and entertaining how humans make themselves at home within this world. In my pictures, I want to leave space, literally and figuratively, for personal associations. They should invite the viewer to connect them with their own memories. The motives I choose are often ambivalent, likable, and strange—all at the same time. I think many of my photographs have that ambivalence. It depends on the viewers mood or their story whether they find them comforting or eerie. By framing my photographs differently than before – the Norway series reflects the restlessness and disorientation that I feel in my life – influenced by my environment and the current affairs. My work process always starts with a research on site. After documenting my first impressions and ideas with digital photographs/polaroids and notes I then decide for the motives and topics that are of most interest to me. During that process, I develop a story. The medium I choose for my photography is a large format camera on 4x5 inch film. I want each picture to reflect the essential essence of its content. In Dale, I had a studio for the first time in my life, so the arranged nature still lifes of the Dale series are a new genre in my work.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Der Greif #8«

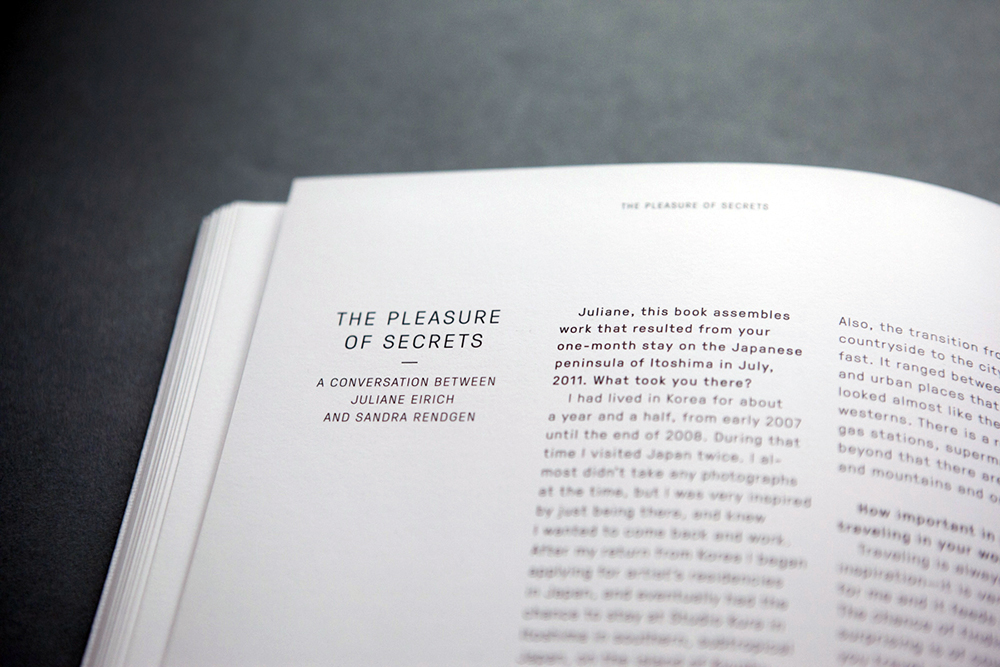

The Pleasure Of Secrets

Oct 20, 2015 - Juliane Eirich

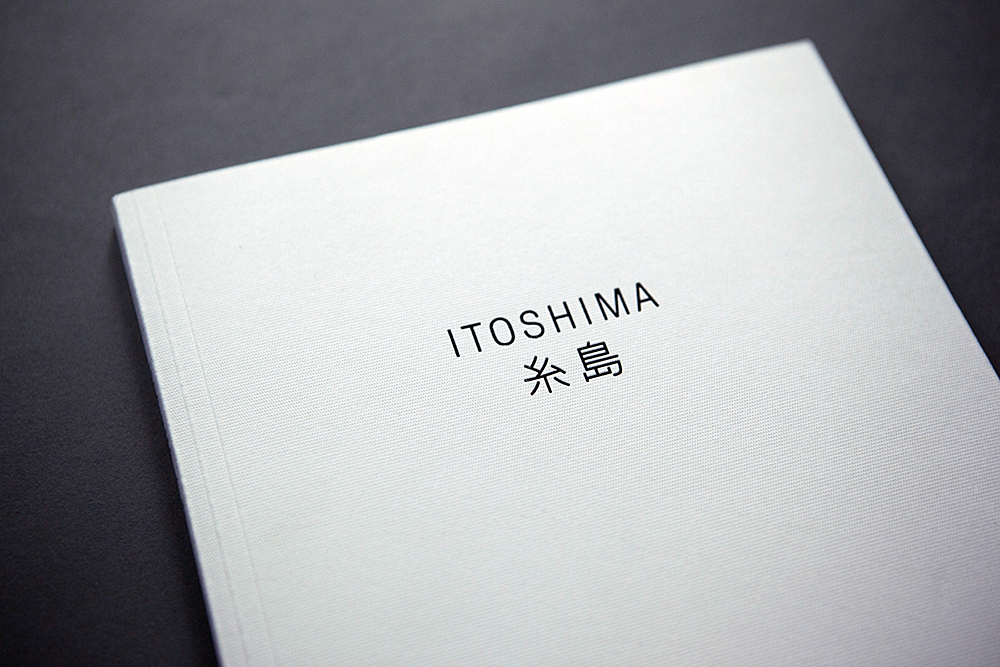

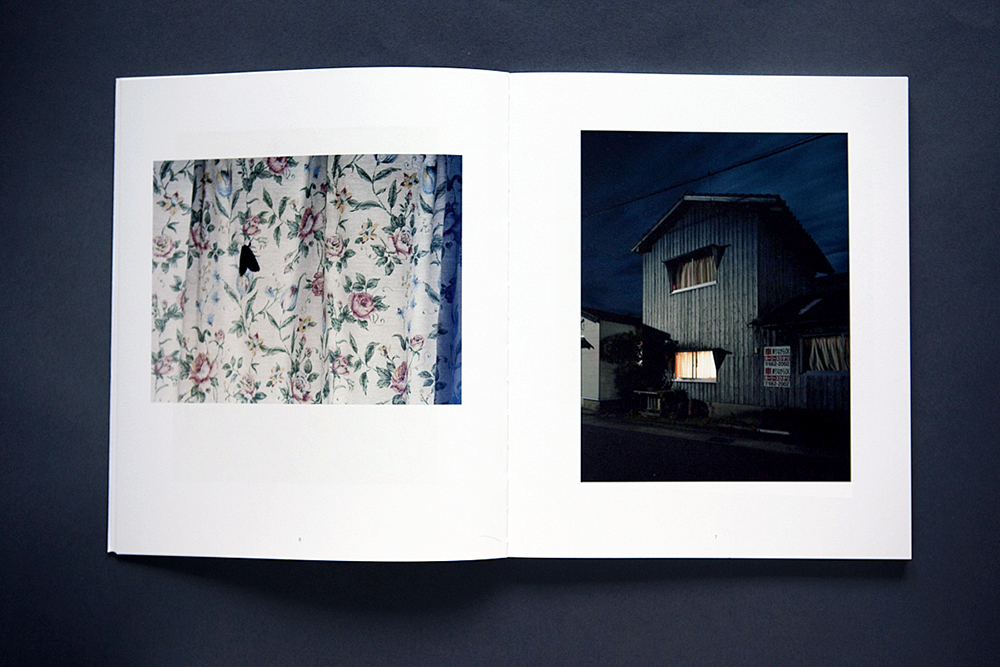

Today I would like to publish the interview that can be found in my monograph Itoshima published by Peperoni Books designed by Studio Workshop. In 2013 I spoke with my friend, art historian and author Sandra Rendgen about the series, Japan and my way of working: THE PLEASURE OF SECRETS A conversation between Juliane Eirich and Sandra Rendgen Juliane, this book assembles work that resulted from your one-month stay on the Japanese peninsula of Itoshima in July, 2011. What took you there? I had lived in Korea for about a year and a half, from early 2007 until the end of 2008. During that time I visited Japan twice. I almost didn’t take any photographs at the time, but I was very inspired by just being there, and knew I wanted to come back and work. After my return from Korea I began applying for artist’s residencies in Japan, and eventually had the chance to stay at Studio Kura in Itoshima in southern, subtropical Japan, on the island of Kyushu, for one month in 2011. I enjoyed great conditions there, I stayed in a small house in the countryside that I had all to myself. It was important for me not to be in the city; I really wanted to be in nature. I had my own bicycle and I took long rides between the ocean, rice fields, and mountains. The region has both very rural areas as well as bustling cities. I was amazed since I had not expected this variety. Also, the transition from the countryside to the city is very fast. It ranged between rice fields and urban places that sometimes looked almost like the cities in westerns. There is a row of houses, gas stations, supermarkets, and beyond that there are rice fields and mountains and ocean. How important in general is traveling in your work? Traveling is always a source of inspiration—it is very motivating for me and it feeds my curiosity. The chance of finding something surprising is of course bigger when you travel. In a foreign country you are more open and able to focus on little details—be it the light, the flora, or even products in the supermarket. I tried to intensify that spirit in Itoshima. When you arrive somewhere, the brain is very fast to adapt to the new surroundings. After about three days, you start thinking, “Oh yes, I know that house!” So what I did was, I used the first three days to bike around and take many digital photographs and notes. I literally documented these first days, because I knew that this newness would go away. It was great since I collected a lot of material that I could look at later. I would then bike back to a location when there was better light, or I kept it in mind as a topic or an inspiration. I tried to preserve that really fresh spirit of traveling. In which way was this trip different from your earlier experiences in Asia, for instance in Korea? By the time I had arrived in Japan, I was already used to traveling and living in Asia and being a foreigner. Additionally I had more life-experience. However, staying in Japan was very different from my experience in Korea. First of all, the two countries are very different from each other. Second, I was staying in Korea for a much longer period of time and studying at the university in Seoul and I was able to learn the language fairly well. In Japan I felt more like a visitor. But for some reason, I felt strangely comfortable and safe there, as if I couldn’t get lost. Another fact that made a big difference was that I changed my way of working—it was much slower. In Korea I had done a project where I took one photo a day for a diary, which forced me to work faster and create an image every day. In Japan I really took my time. It was the first time that I did a big project with a large format camera, which is a totally different way of taking pictures. I am a very slow photographer in general, but Japan was kind of the climax of taking one’s time. So how did you compose your project, how did you find your images? I should probably mention that I had mixed feelings about Itoshima. I went during the summer of 2011. A few months before, the earthquake and its aftermath had destroyed the Fukushima nuclear power plant and there was no reliable information available about whether there was a real threat or not. A lot of people told me not to go—even though Fukushima is around 1,000 km away from Itoshima. So on the one hand there was this very strange fear of invisible radioactivity. A feeling of nescience though through no fault of my own. It was a feeling of uneasiness that I can relate to, because I have had this feeling in other situations in my life—more so in our current time. On the other hand, when I arrived I immediately had this immense, very positive energy. I knew that I was in the right place; I enjoyed every minute of my stay. These were the conflicting feelings I had experienced when I started exploring the peninsula. One of my main themes and interests is how humans and nature interact; I always look for traces of that relationship. The places I find are often ambivalent, likable, and strange—all at the same time. I think many of the photographs have that ambivalence, it depends on your mood or your story whether you find them comforting or eerie. Also, this kind of slowness was really important—my mode of transportation was cycling, that was the speed I had. I am very strict in regards to my photography, and I choose my images very carefully. I do not take many photographs, and I really knew what I wanted to do with those that I did take. Sometimes the images come to me. I pass by and they urge me to take their photo. Like when you pass people and they ask you to take their picture. Since you select your images with such care, do you consider yourself documenting something that is there, or do you feel like you are constructing an artistic reality? I see myself somewhere between these two extremes. Of course I am documenting what I see, I work with analogue photography. Even if the photos sometimes look artificial, I hardly crop or manipulate them. I am often asked if I retouch the images a lot or if they are something like digital renderings, but that is not the case. These places really exist, so if you would happen to pass by, you would recognize them. But of course, I am a photographer and my decisions are very subjective. Maybe next to a bush, ten thousand people are waiting in line in front of a soccer stadium, but they are not in my photograph. You always crop nature, you always edit something out. That is subjective, and that does change reality. To what extent do you see your work as concept-driven, do you first think about a “road map,” or is it you going out there and looking for images? I try to be open, to create situations where I can let things happen. That also involves immersing myself in places, situations, and also in foreign cultures. For instance, the books I read while I was on Itoshima, the music I listened to, and the movies I watched. To name some: I was very influenced by a book by the Japanese writer Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows. It is an essay that contains sixteen sections about Japanese aesthetics. In one of them he describes why old Japanese houses have these dark corners and shadows. In Germany walls are usually white, you want to see everything. In traditional Japanese houses there are these special shades that create a kind of artificial darkness. There is this love for myth and for not knowing everything—in the pleasure of secrets. I have been a fan of Yasujirō Ozu’s movies for a long time. I am really fond of the way he portraits humanity in such a gentle way. Of course, his films are classics and I had watched many of his films in Germany, but watching them in Japan was different, because I was sitting in a house that looked like a film set from one of those movies. It surely inspired me to take photos in the old lady’s house I was staying in. I had a radio there that I switched on every morning while having breakfast. I wrote down all the songs they were playing that I liked. It was a Japanese station that played American songs from the nineteen-sixties to the nineties. All these influences have inspired my work. But then again I can read so many things, but in the end I have to go out there and find places. I cannot find these places on Google Earth. For example for my nighttime images it has to be a certain night with a certain light. Doing it, I guess is the concept I start with. Doing is, the new searching. Everything you find on Google already exists. It also has to do with the physical experience of being outside, feeling the wind and the rain. I got soaked so many times by heavy rain and got caught in thunderstorms—and I sweated a lot, since it was very, very hot. I am using each of the senses while creating new work. Talking about a physical experience: During my nocturnal shootings in Itoshima, I was constantly surrounded and often covered by spider webs, spiders, bugs, caterpillars, and other insects. One time, two spiders lowered themselves from my hat at exactly the same time in front of my face and once several worms fell out of a tree on my shoulder. You mentioned the large format camera you worked with, you mostly work on film. How does that shape your images? The process of working with analogue photography is very different from digital photography—you have to focus on what is in front of your camera instead of what is on your screen. You are less distracted and really pay attention to what you are looking at. You are communicating very directly with your motif. Also, you have a chance of failing that you need to accept. It can happen that the photograph is blurry or that you’ve somehow messed it up. You cannot see that right away. I developed my photos in Japan since it was really important for me to check whether everything worked. I had to ship the film to another island in Japan, though. With digital photography you know right away: “I got the picture.” In my case I settled for “I think I have it,” and then four days later I got it back and saw the results. This process is circuitous but rewarding. I enjoy waiting for the picture. Working this way is a nice combination of obligation and passion. Of course in the past, this slow process was nothing to even talk about, but since now there is digital photography, to work that way is a decision I made intentionally. I want my images to be the opposite of a snapshot. This has evolved in my work as if it were an invisible power pushing me towards that way of working. It is the experience of focusing on one thing and taking time together with the haptic pleasure of working with film and a camera that you need to operate manually. It requires craftsmanship. The analogue camera is also less sensitive regarding rain, humidity, heat, and cold, so I am able to shoot in more extreme weather situations. There are no people in these images. You are tracing the results of human actions, but they are never seen in action. Yes, I think these traces tell a lot about humans. If there is a face on the photo this is what people immediately relate to. What is the expression on their face, what is the story of this person, do I like this person or not? This is not my topic. I wanted these images to be open, to leave more space for thoughts and associations. Who created this place? What could it be? Actually, I see my photographs as architecture—or flora-portraits. There are two palm tree photos, for example, that I think look like family portraits. While, the houses are characters, they evoke stories. They stand for a certain era or for a certain biography. Ending with one general question, what would you say is your driving force as a photographer? I am incredibly curious about places, people, and stories. Being a photographer was not a natural choice—it is not like I always took pictures as a child. I started this all of a sudden and the more I do it, the more I’m into it. I always say being a photographer is like having a license to be curious. If you say to someone, “I am a photographer, can I go on your rooftop?” they might say yes. If you just say, “Hey, you have a cool rooftop, can I check it out?” they will probably say no. It is a door opener for many places you would usually not see, because people accept that as a photographer you want to see as much as you can. My professor for architecture photography told me that when you take pictures of a building, the most important person is not the CEO of the company or the architect of the building, but the doorman or janitor. This is very true, because he is the person I will deal with while at the site. This was an eye opener, because I realized that there is a sociological aspect in this approach to photography. I am able to meet and talk to people from very different backgrounds. I realized how much everyone is usually confined to their own microcosm. Talking to people makes you understand how many things are extremely subjective. All this is a huge driving force for me. It feels like this curiosity will always be continuously growing. If you immerse yourself in a situation, something will invariably happen. If you realize how doors can open, you get addicted to that and will act accordingly. You are more open and things happen faster. Through my work as a photographer, I am also more aware of my own subjectivity and because of it, I pay a lot of attention to my dreams, memories, and interests. I want to see as much as possible of the world. It is hard to put into words what it is that I am looking for, but I always know when I find it. Most of the people I saw during my nighttime photo sessions in Itoshima were fishermen, so I thought, while riding my bike, that I am also a kind of angler in the figurative sense. Just that I am angling for stories and for pictures. And that most of the time it is me, that ends up getting hooked. The whole Itoshima series can be found here. A text about the series written by Elisabeth Biondi can be found here.

Fail Better

Oct 19, 2015 - Juliane Eirich

Short after I started photography school in Munich I went on a trip to Cuba. At that time we just had learned how to develop and enlarge Black and White pictures. Thus I only took B/W films with me. On site I did not think about it anymore, since through the viewfinder, everything is still in color, no matter what kind of film is in the camera. When I came back from Cuba, everybody said: "Wow, I am so curious to see the photos you took! They must be so colorful!" When the first person said it, I confidently and proudly answered: "No, I only took Black and White pictures!" But when more and more people said the same thing, I felt horrible and was really regretting that I did not even think about using color film. Especially since I did not have it in mind when I was photographing. When I finally looked at my B/W pictures, I was certainly quite disappointed and never really looked at them again. Last year, I reorganized my archive and saw them again after 14 years. I had to smile when I saw this series of a colorful butterfly on green grass all in B/W.

Animals Doing Their Thing

Oct 17, 2015 - Juliane Eirich

Due to a competition, I was able to work with a digital medium format camera for the first time. I always wanted to try to do animal photographs and finally saw my chance to do it. With my large format camera, every creature will have left the frame, when I am finally ready to take a picture.

Bäckerei Schmidt

Oct 16, 2015 - Juliane Eirich

mg src="https://dergreif-online.de/www/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/01-Bäckerei-Schmidt-908x700.jpg" alt="01-Bäckerei Schmidt" width="908" height="700" class="aligncenter size-large wp-image-55244" /> I moved to Berlin in 2009. Before I moved I imagined to do a Berlin series, in the same way, that I am usually photographing series in other countries around the world. I started looking for motives and so far, I found one per year that interests me. So it is officially my slowest project and I will be happy to introduce it in 2029. Today, I am proud to present the one photo from 2011: Bäckerei Schmidt. http://www.globalyodel.com/yodels/bakery-schmidt/

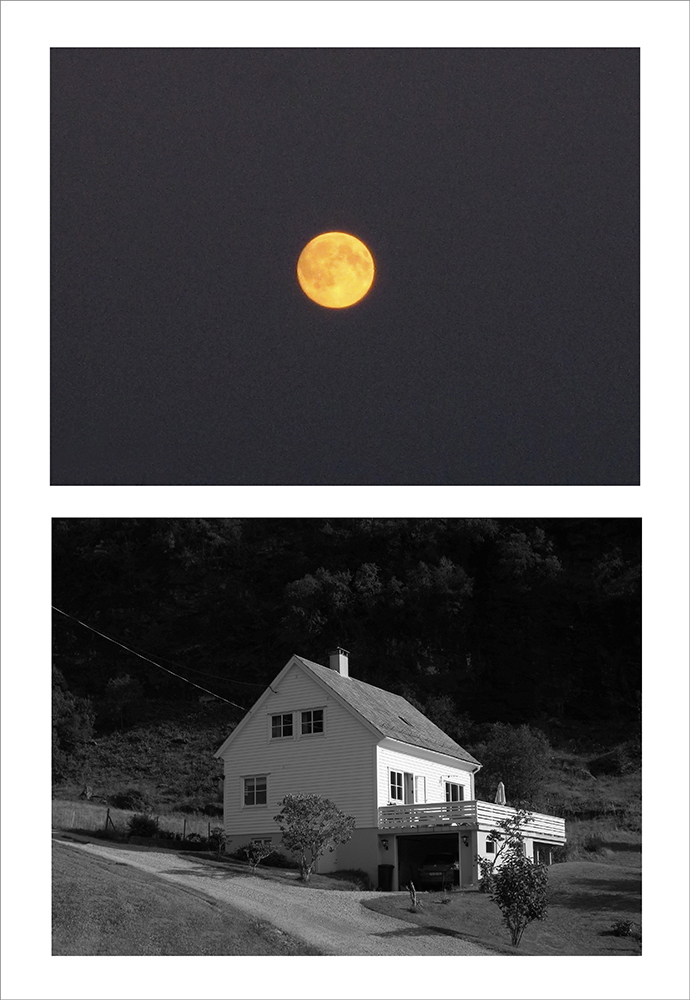

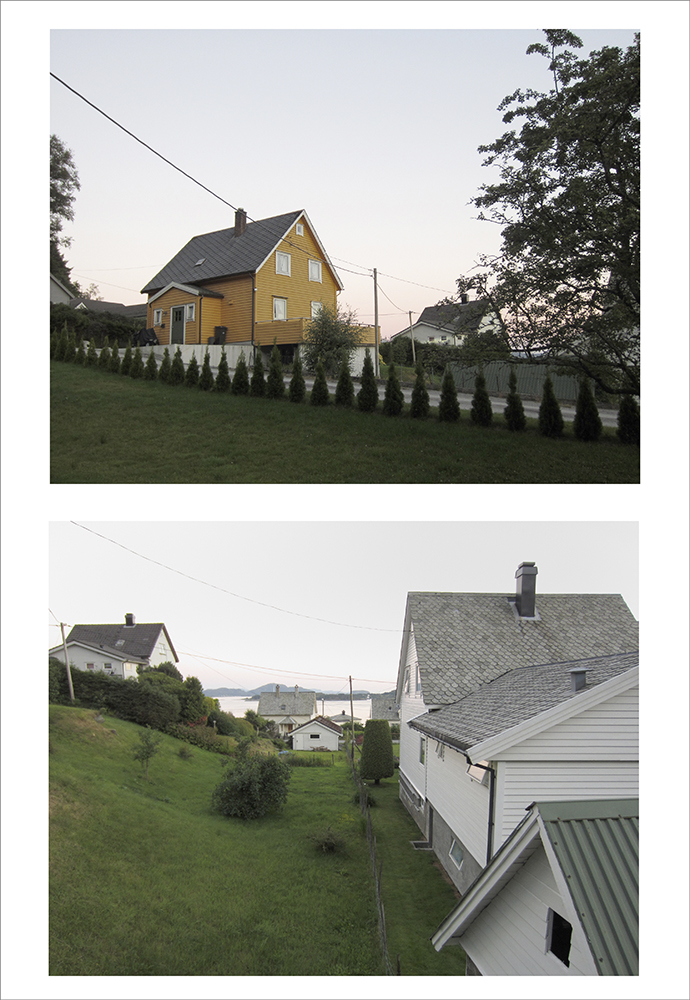

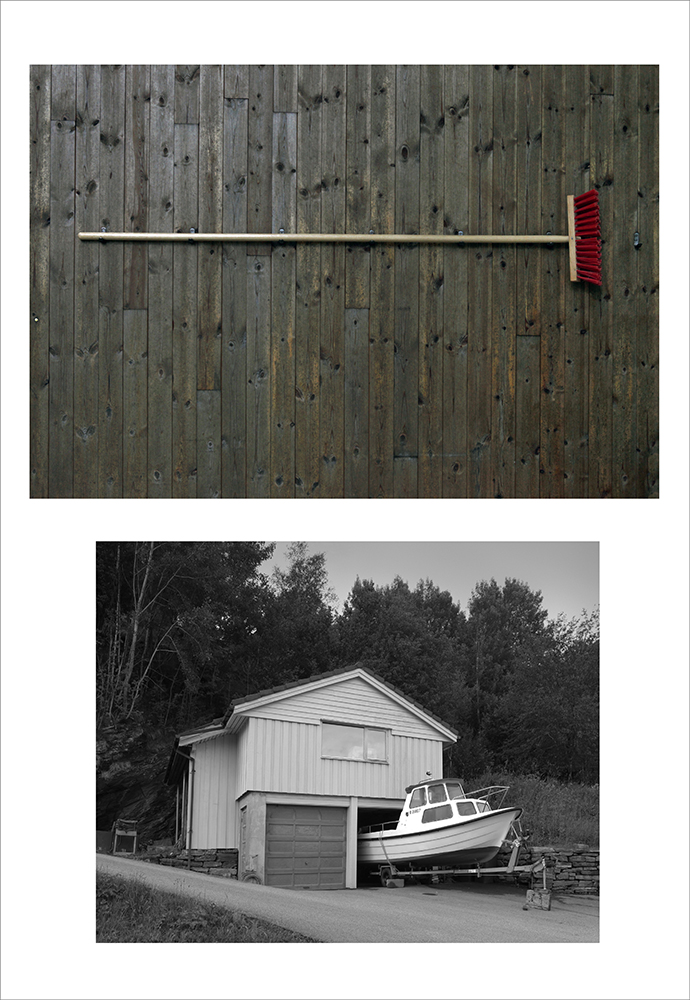

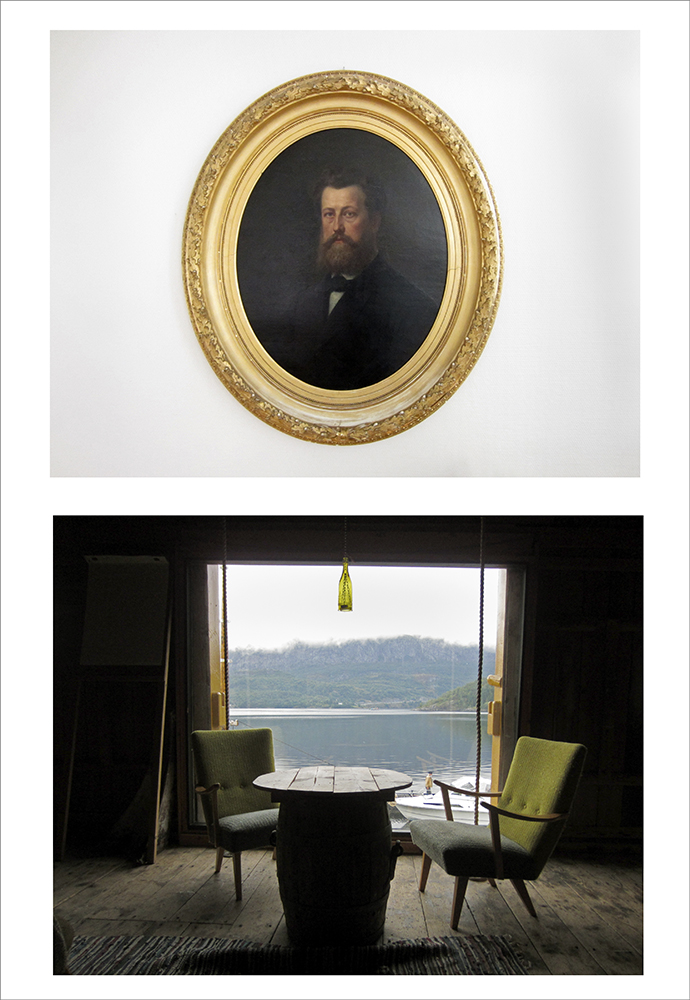

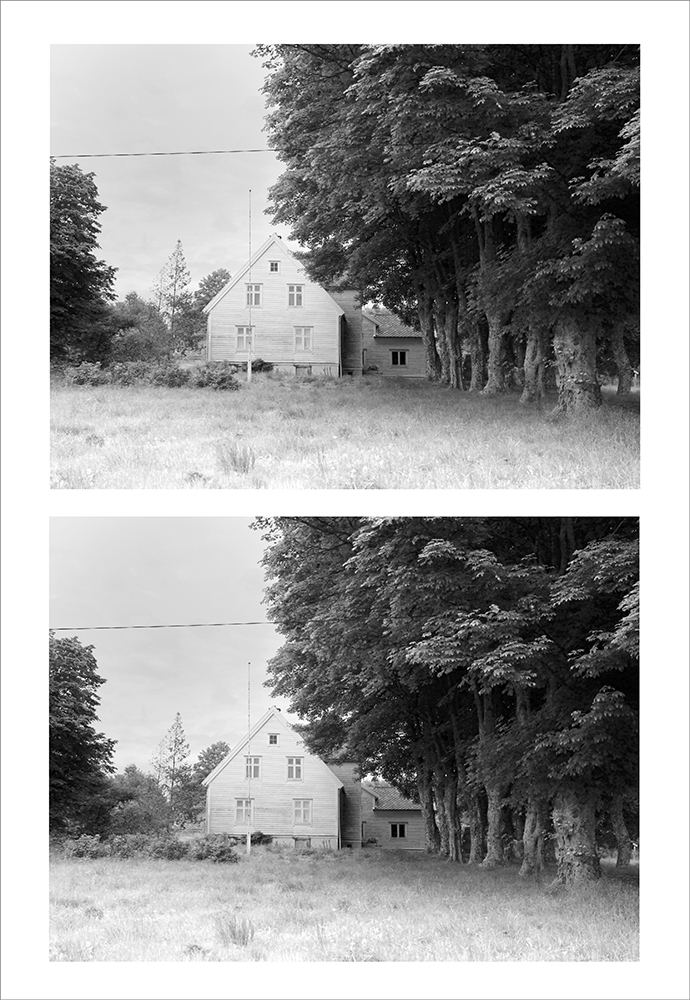

Behind the scenes of the Dale Series

Oct 15, 2015 - Juliane Eirich

When I arrived at the residency in Dale in July 2014, I was immediately amazed and shocked about the beauty of Norway. Shocked, because I knew it would be very difficult to find the motives I am usually looking for, since it is just too beautiful. For sure, I could not just photograph a red house on a Fjord. I told myself to keep calm though and give it some time, since it was the first time in my life being able to work two months exclusively on one project. Plus, it was the first time I had a studio. I am adding a photograph of my studio, to show how nice my working conditions were. I am a very slow photographer. I work with a 4x5 inch large format camera on film. I am very strict in regards to my photography and choose my images very carefully. I do not take many photos, and with the ones I take I really know what I want to do. My work process always starts with a research on site. After documenting my first impressions and ideas with digital photographs/polaroids and notes I then decide for the motives and topics that are of most interest to me. During that process, I develop a story. In Norway I took a lot of these notes to collect ideas. More than ever before, since it took time to understand the visual possibilities. Usually I don't show these digital notes, but I realised, I want to change this. They are important for my work and they influence my final edit to a great extend. Also I like it a lot, when artists explain how they work. So in this blog, I am showing my notes for the first time. I am presenting them exactly the way I used them in Norway. I put two photos on one A4 sheet. Originally I put two in order to save ink when I print them, but then I liked it and also did it to already get a feeling for pairs and matching topics. Some of the notes that I liked and I wanted to reshoot with the 4x5inch camera were impossible to repeat for different reasons: Sometimes, nature already had changed. When I came back to the location, certain flowers were out of bloom, certain currents did not hit the same rocks anymore or heavy rain had stopped. On the other hand, life just goes on: On one of the houses I wanted to photograph there was a balcony added that totally spoiled my photo. (In case you wonder: There were three weeks between my note and my arrival with the large format camera.) This is how slow of a photographer I am. Sometimes grass was cut, sometimes a car left and never came back, sometimes people did not switch on the light in their hallway anymore. When I am at a place I find out a lot of details of the people that are living there. I know who goes to bed late, I know who had a visitor, I know who always parks differently etc. It might seem a littlebit spooky, but I guess it is the duty of a artist to observe. I actually feel a lot like a writer, when I am working. I keep myself entertained by inventing stories in my head, which visitor might have been there or why this person sleeps so late. The way I work fits my personality. I am very curious and even though there are usually no humans on my photographs I am a humanist. I enjoy the physical experience of being outside, feeling the wind and the rain. I got soaked many times by heavy rain and I sweated a lot, since it was actually a really hot summer for Norway. Sometimes, I do have company during my photo sessions. In Norway I had friends visiting that came with me. Additionally the other artists in residence got into making these spontanious roadtrips together. I am pleased when I have company too, because you share the adventure, you can enjoy the food and tea you bring more and you can be more courageous especially at night. Talking about night: When I was in Norway, there was no real darkness due to the summertime. It was very interesting to experience, but tough for me since I tend to find many of my motives at night. But necessity is the mother of invention: I found an abandoned tunnel and I worked with the strong sunlight and underexposures, so there actually are nights shots or night looking shots in the series. There are three real night photographs in the Dale series. I took all of them in the very last night, when there was finally some real darkness for a few hours. The Dale Project was kindly supported by the Nordic Artists Center Dale, Norway