Allyssa Heuze

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

Luke Withers - Wireless

Nov 22, 2017

“The signals came to us silently and invisibly from the island rock, whose contour was scarcely visible to the naked eye, dancing on that unknown and mysterious agent the Ether”

In 1897, the first wireless signal was successfully transmitted across a body of water, from Flatholm Island in the Bristol Channel to Lavernock Point on the Welsh coast. This transmission marked the beginning of the ‘Victorian Communication Revolution’ that arguably catapulted the World towards Globalisation.

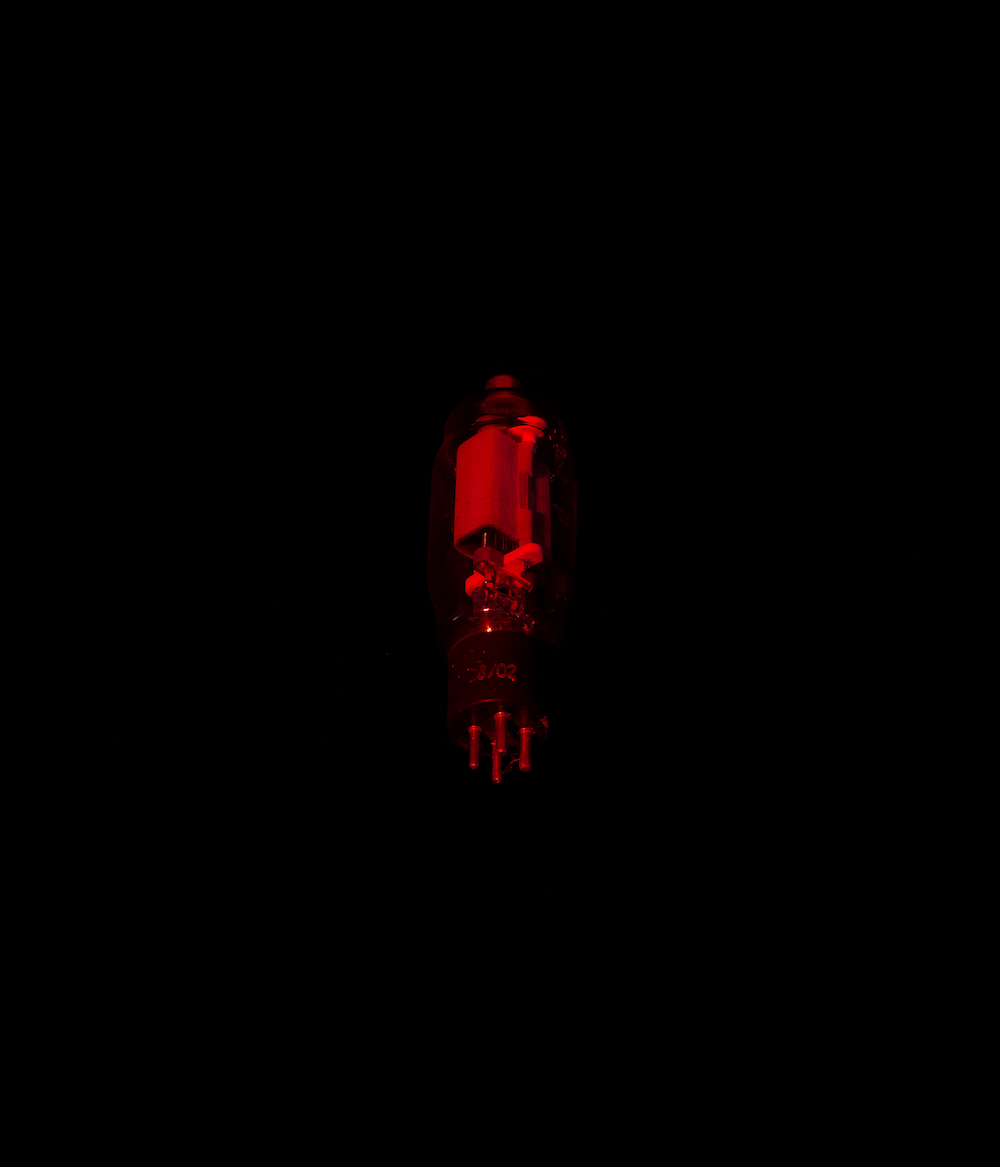

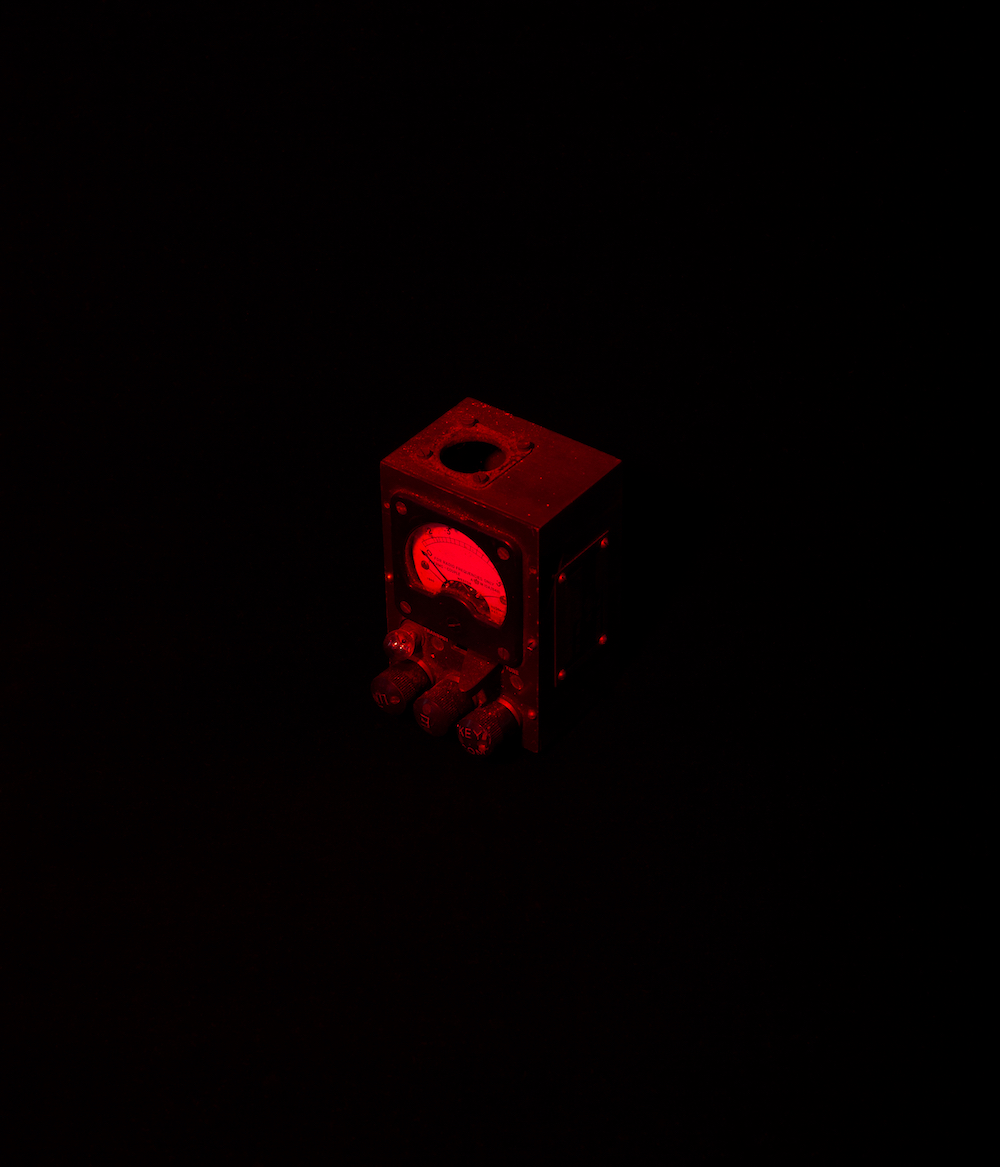

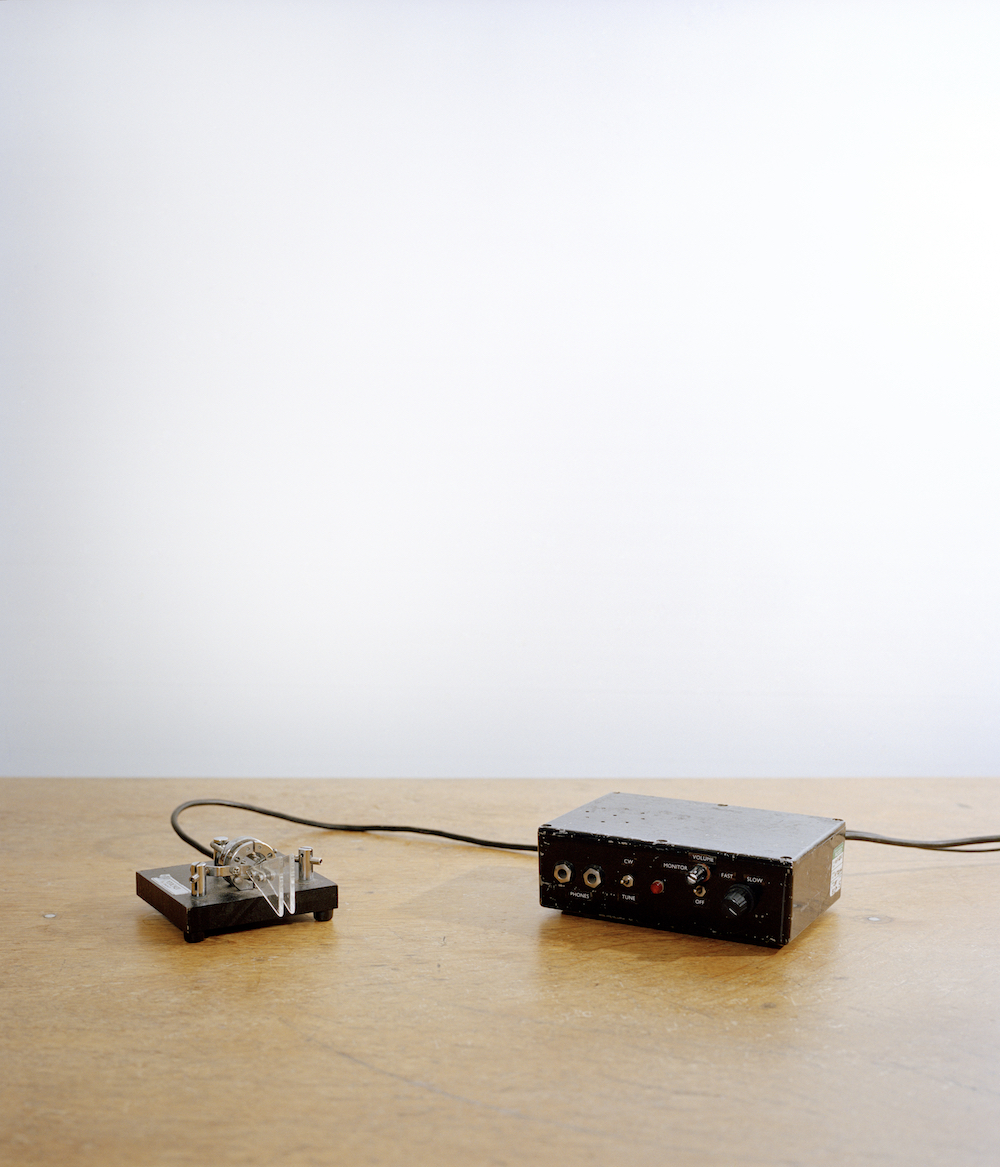

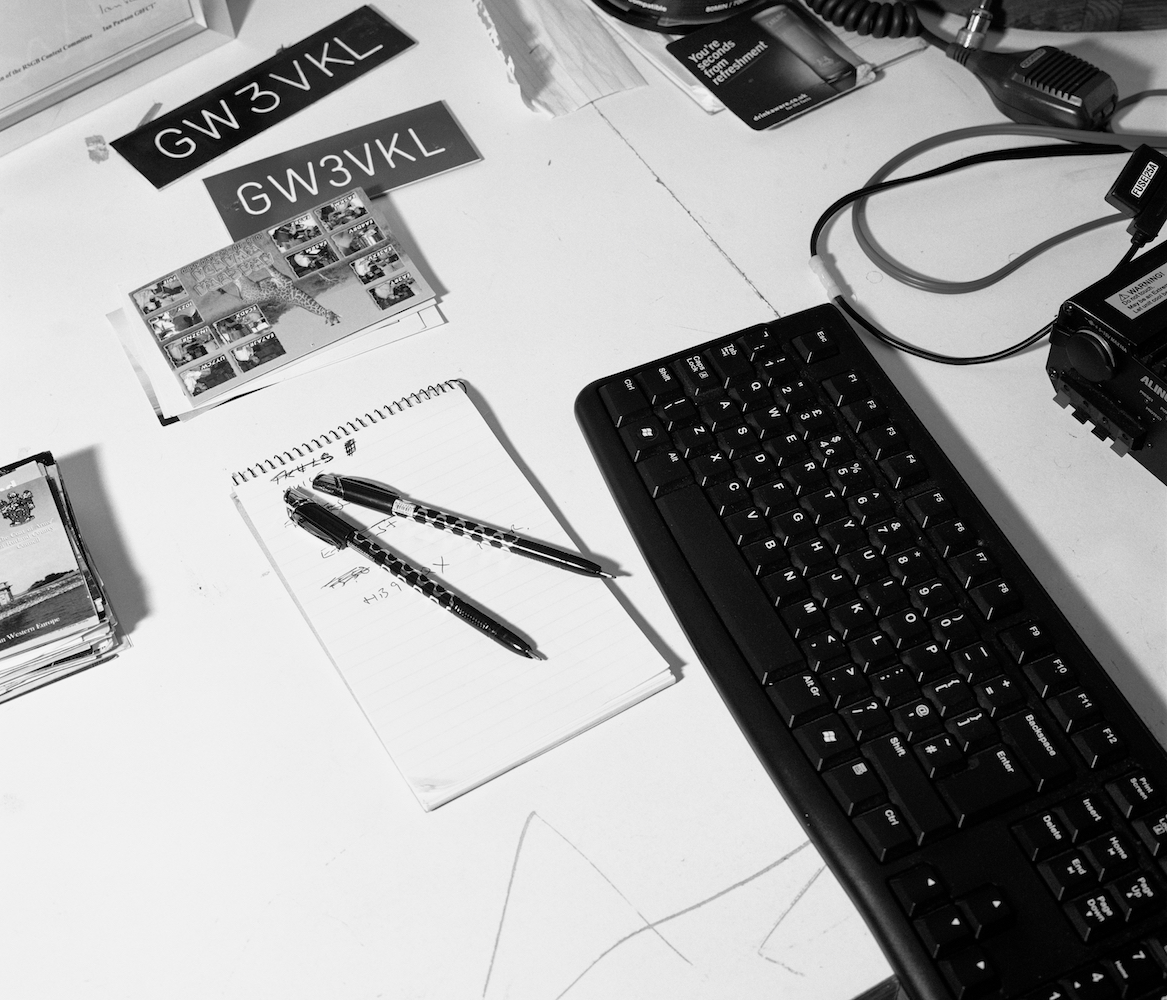

Today, Amateur radio enthusiasts still experiment from the same two points; transgressing the obstacle of the Sea with equipment almost unchanged from those early tests. They display an innate human desire to connect and communicate, and identify themselves using short alphanumerical codes known as ‘Call Signs’. These signals are transmitted and received in the form of Morse Code; a truly Global language of ‘Dots and Dashes’ represented by pulses of light or sound. The sequences reference their location in the World and act as their sole identifying characteristic whilst attempting to contact other users.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Der Greif #9«

Signals and Seas

Nov 26, 2017 - Luke Withers

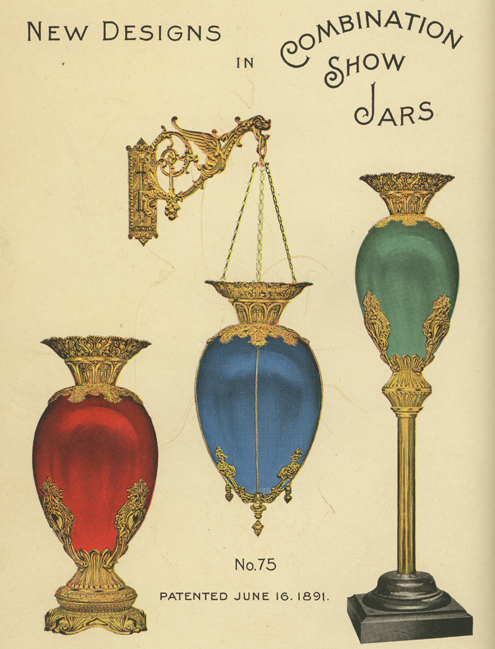

Prior to radio communication, islands and ships could communicate only with visible signals like flags and lighthouses, the horizon was therefore the limit of communication. This isolation is one of the primary themes of Rudyard Kipling’s short story ‘Wireless’, which predates the first commercial uses of wireless telegraphy but predicts the nature of it. It’s an account of a chemist and some friends who are experimenting with radio technology whilst the pharmacy’s show globes sway outside in a winter storm. As they attempt to contact another radio enthusiast, they inadvertently pick up the signals of two ships on the coast, which are attempting to contact each other but failing to detect each others messages.

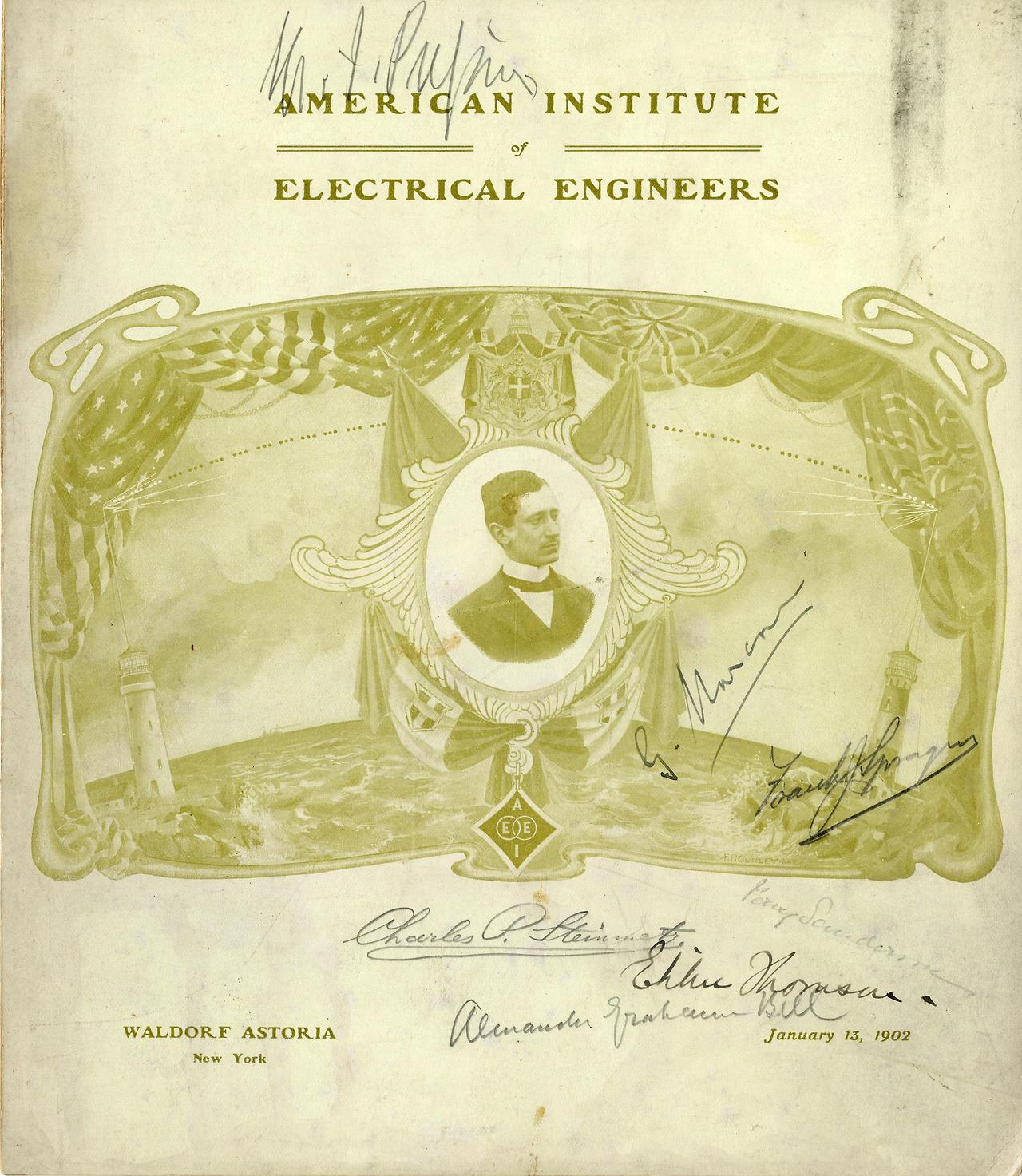

I found the imagery of Islands and lighthouses reflected on a dinner invite from 1902 celebrating Marconi’s first transmission across the Atlantic, with which he wirelessly connected the American and European continents. On this invite was depicted two lighthouses at the ends of landmasses, connected by the dotted line of a Morse Code transmission reaching across an open sea.

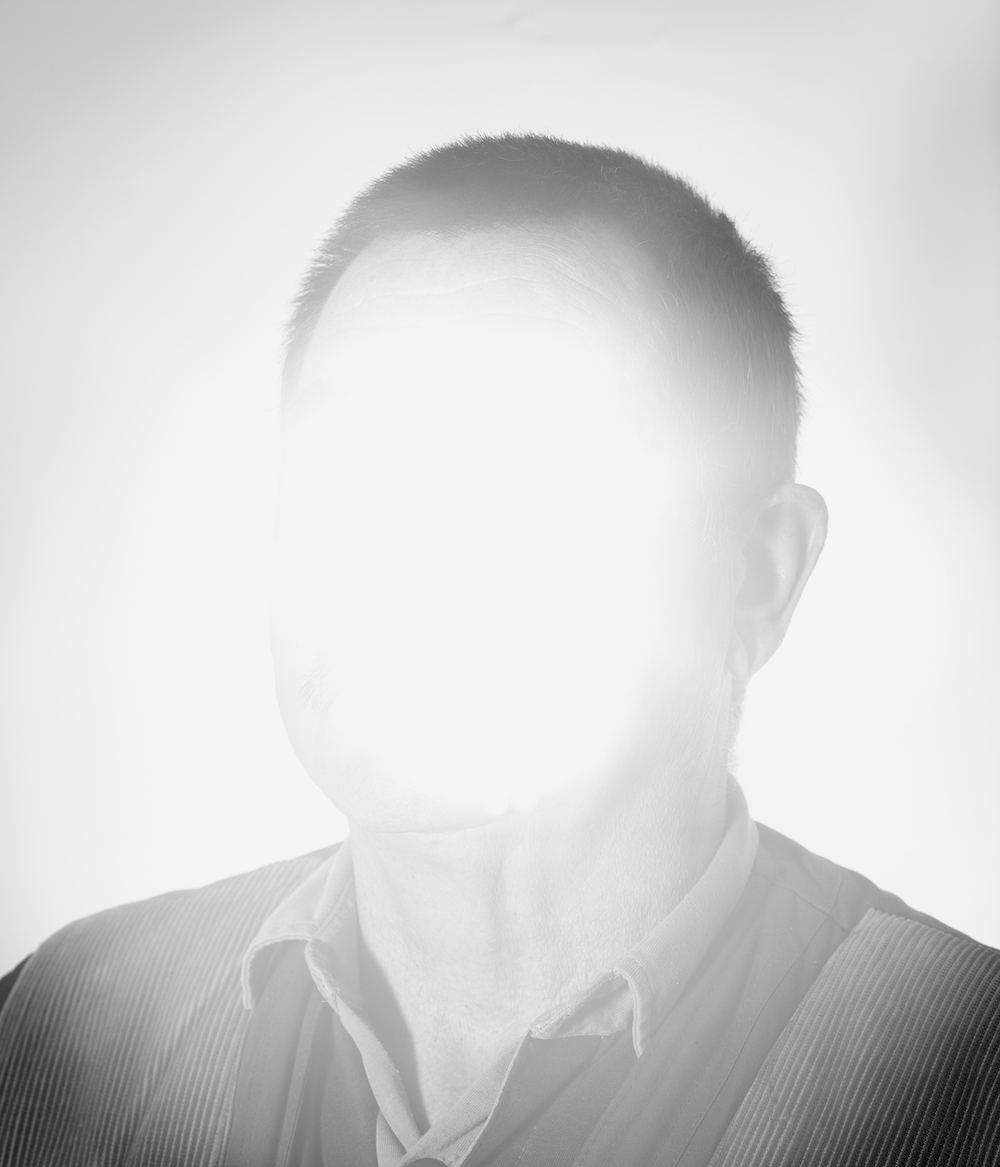

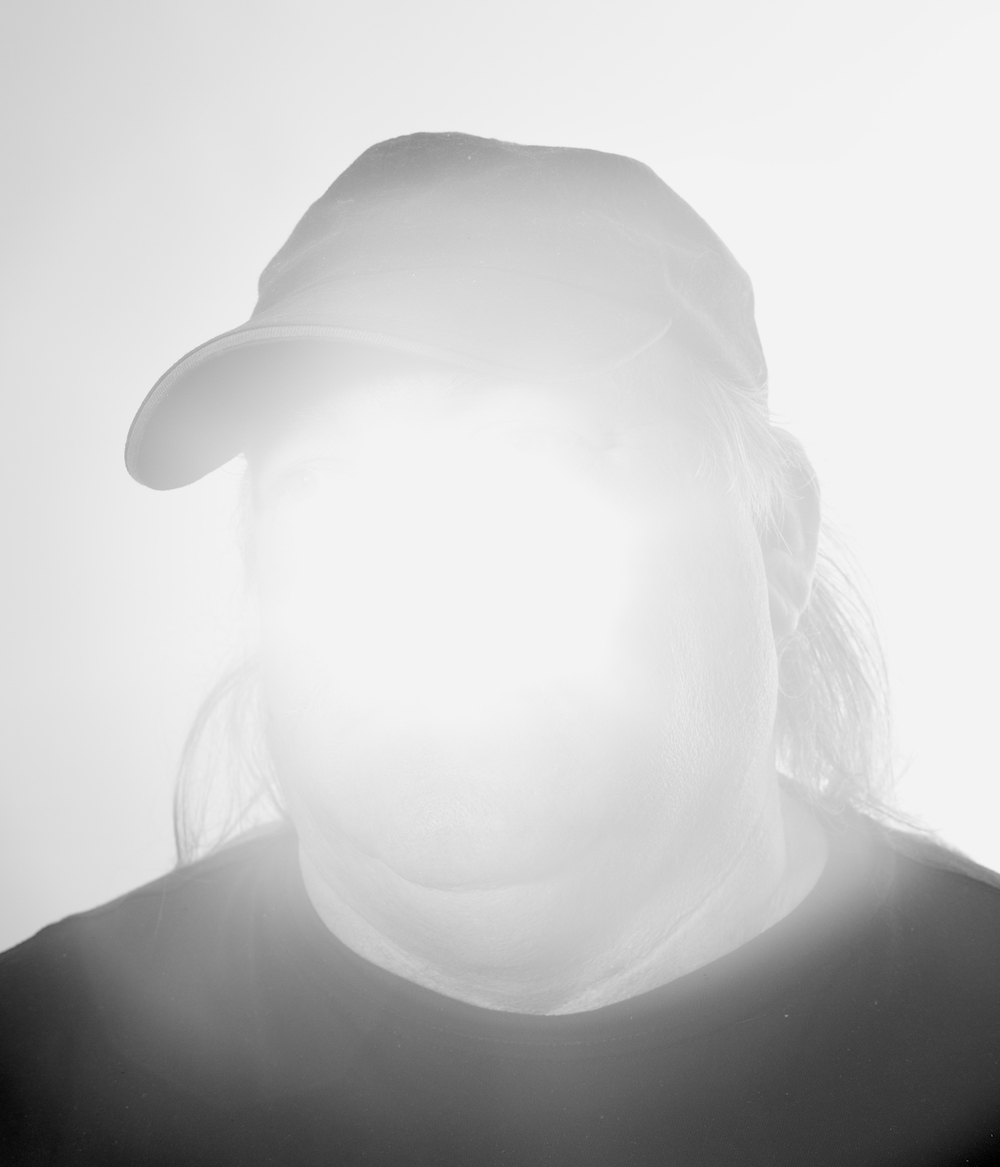

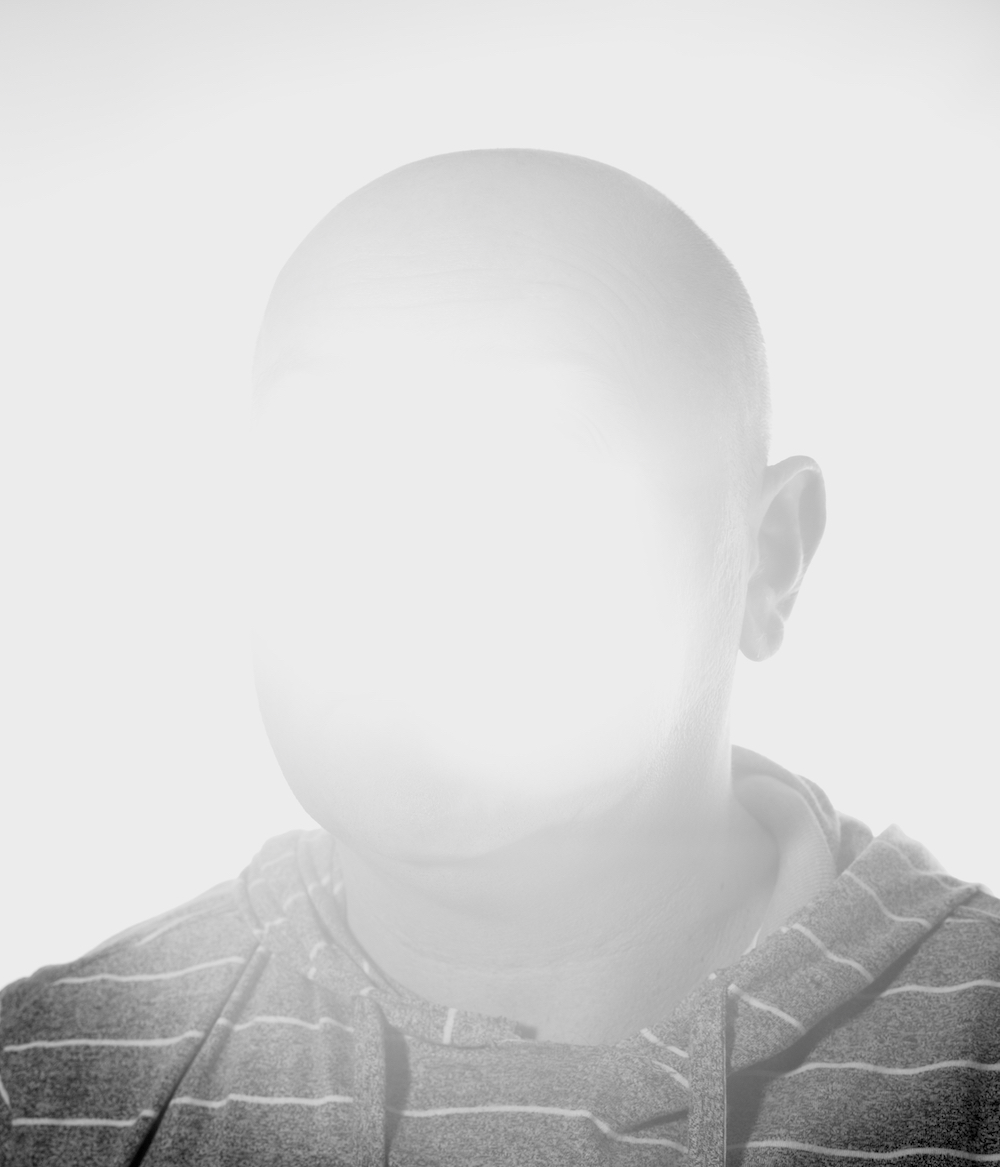

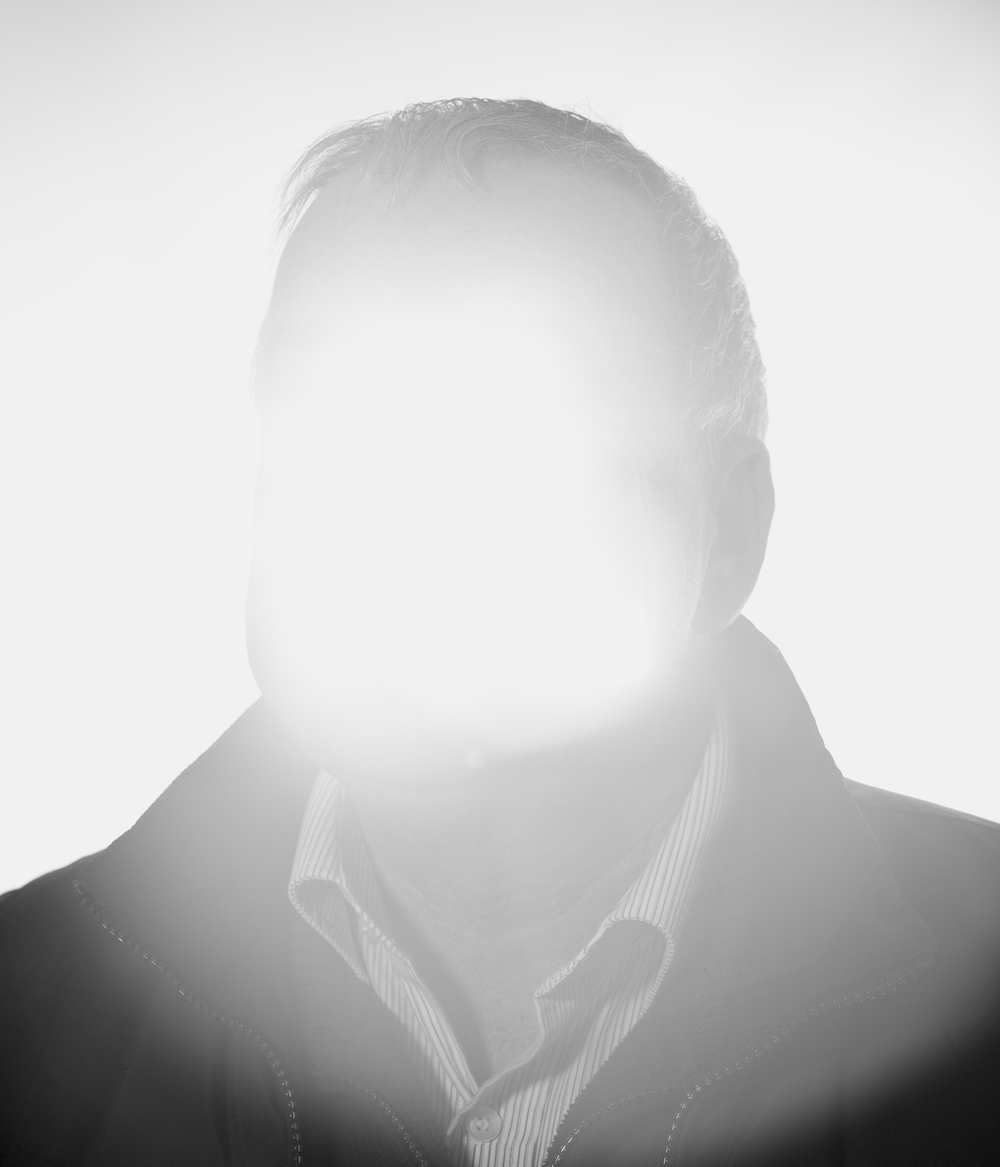

Evoking the solitary experience of islands and sea farers was something that I hoped to do in the ‘Wireless’ series. I incorporated the imagery into the work by photographing Flatholm’s own lighthouse and in a portrait series of radio enthusiasts who still operate from the same two points as Marconi’s initial success. In these portraits, the individuals faces are obscured by a burst of flashlight to reflect the common use of Morse Code by both lighthouses and radio amateurs. Morse is a global, binary language transmitted as sound or light, and written in a succession of dots and dashes. For the radio operators its the primary medium on which an individuals unique ‘call sign’ is transmitted, this is an this alphanumerical code that denotes their identity and their location in the world.

In a similar manner, Lighthouses transmit a unique sequence of white or red light which denotes their identity, and thus their location. I felt in these common transmissions, was reflected a solitude, isolation, and a strive to connect, which was coherent throughout the subject matter, and which did not require me to reveal more of the individuals identity than they themselves transmitted via their call sign. As such their unique sequence of dots and dashes is included alongside their portrait within the book.

Concentric Circles, Roni Horn’s ‘Pi’

Nov 25, 2017 - Luke Withers

Whilst researching for my Wireless project I was introduced to the work of American artist Roni Horn, in particular her Icelandic photographic series ‘Pi’. It’s a ‘a description of the island´s unique characteristics’, encompassing the experience of island life and confounding on the impossibility of seeing the Arctic Circle. As the name suggests, the series encompasses cyclical themes at a range of levels including the island, the seasons, and the Arctic Circle itself. Horn depicts images of the interior; the wildlife, the tundra, the homes, and snapshots from the most prominent television show, ‘Guiding Light’. These all sit alongside portraits of individuals who inhabit the land and experience its cycles, but she also looks outward to visualise the islands fringes; the coastline and the seas that surround it.

The island experience is reflected in the exhibition layout, where the images are displayed linearly, slightly above the eye level of the viewer, and are placed in a kind of ‘rhythm’ rather than a narrative, which is cyclical, and close-ended. In this way, the viewer becomes immersed in a sea of photographs, as if they were themselves looking outwards from Horn’s Icelandic concentric circle.

Far Near, Near Far

Nov 24, 2017 - Luke Withers

In his essay ‘The Right Distance’, Joan Fontcuberta dissects the relationship between the physical distance of the photographer and the optically transporting quality of the camera lens. He makes an interesting comparison between the experience of the ‘documentary photographer’ and the ‘paparazzi photographer’, one being physically near and optically distant – the documentarian with a wide angle lens – and the other being physically remote but optically near – the paparazzo with the telephoto lens, ‘far near and near far.’

I first used a telephoto lens during my project ‘Wireless’ to photograph the distant islands of Flatholm and Steepholm in the Bristol channel. These were the locations from which many early radio experiments had taken place and where the first successful transmission was received by Marconi in 1897. In my research I had found the event described in the following paragraph:

“The signals came to us silently and invisibly from the island rock, whose contour was scarcely visible to the naked eye, dancing on that unknown and mysterious agent the Ether.”

The theorist Paul Virillo said ‘All current technologies reduce expanse to nothing, they produce shorter and shorter distances, a shrinking fabric”. I wanted to optically collapse the distance between the transmission point and the Island in a similar manner as the new technology of radio had reduced the expanse of the sea between the points. By using a telephoto lens, I could represent the visual and communicative collapse of distance by both photography and radio, which was itself reflected in Fontcuberta’s writing; “The transition to modernity can be interpreted as a zooming in on the object”.

This is an attempt to visually incorporate the operations of radio technology into the aesthetics of the work, by translating its conceptual workings into their nearest visual counterpart. I’ve since used telephoto lenses during projects in Belfast and Gibraltar where the point of capture is as important as viewpoint from that position.

Evidence and Ambiguity

Nov 23, 2017 - Luke Withers

Hi, I’m Luke Withers and I’m the guest blogger for Der Greif this week. I’ll be sharing some work and writing that I find interesting, alongside research and backround to my project ‘Wireless’.

Ambiguity forms a part of my approach to photography, images are naturally ambiguous things, they depend on the context in which we find them to truly perform any ‘meaning’. For me, this is their wonderful potential, it’s what allows Der Grief to exist. Each of the images amongst Der Greif’s pages were made with intention and purpose, which is wilfully offered up to find new meanings through the structural and aesthetic connections that emerge between photographs.

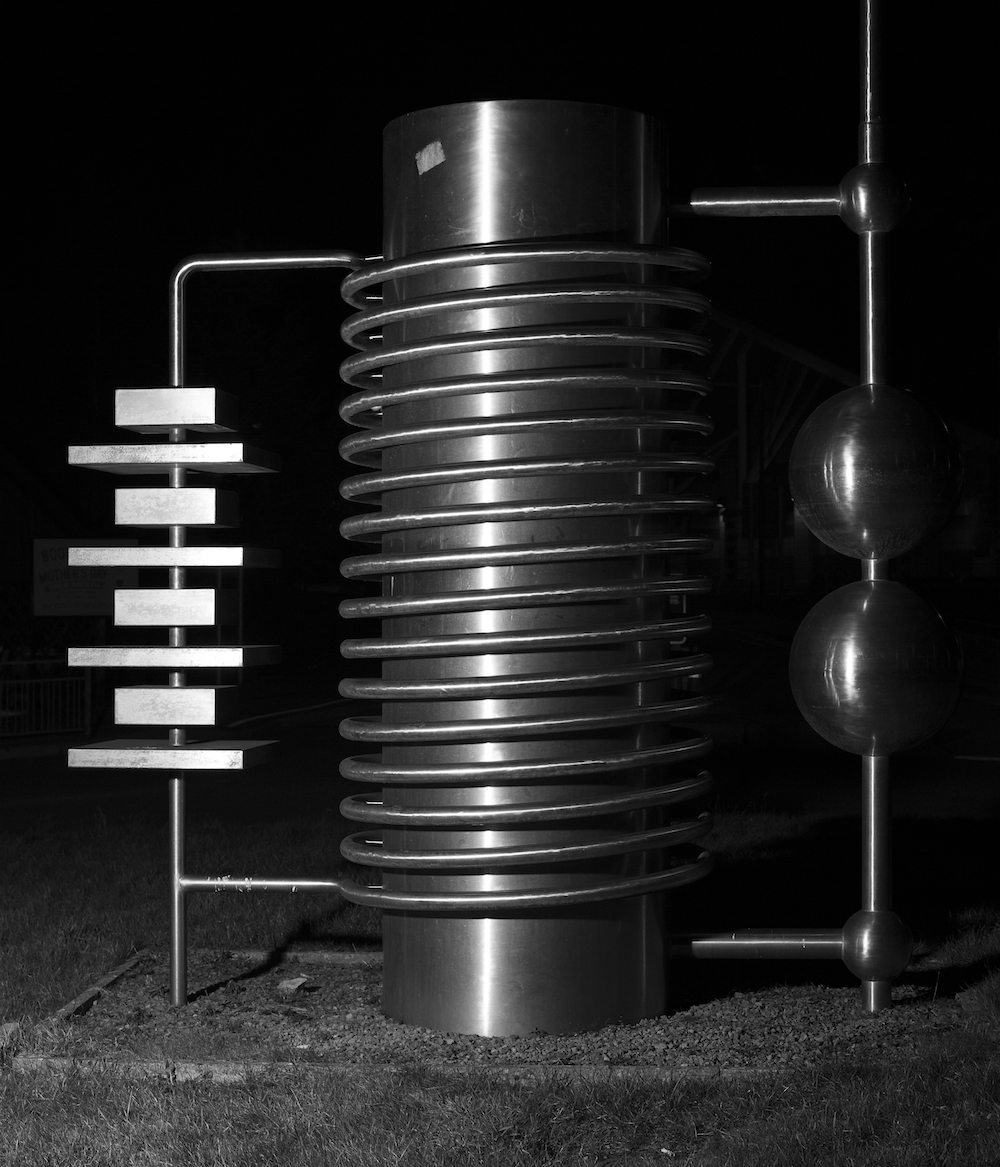

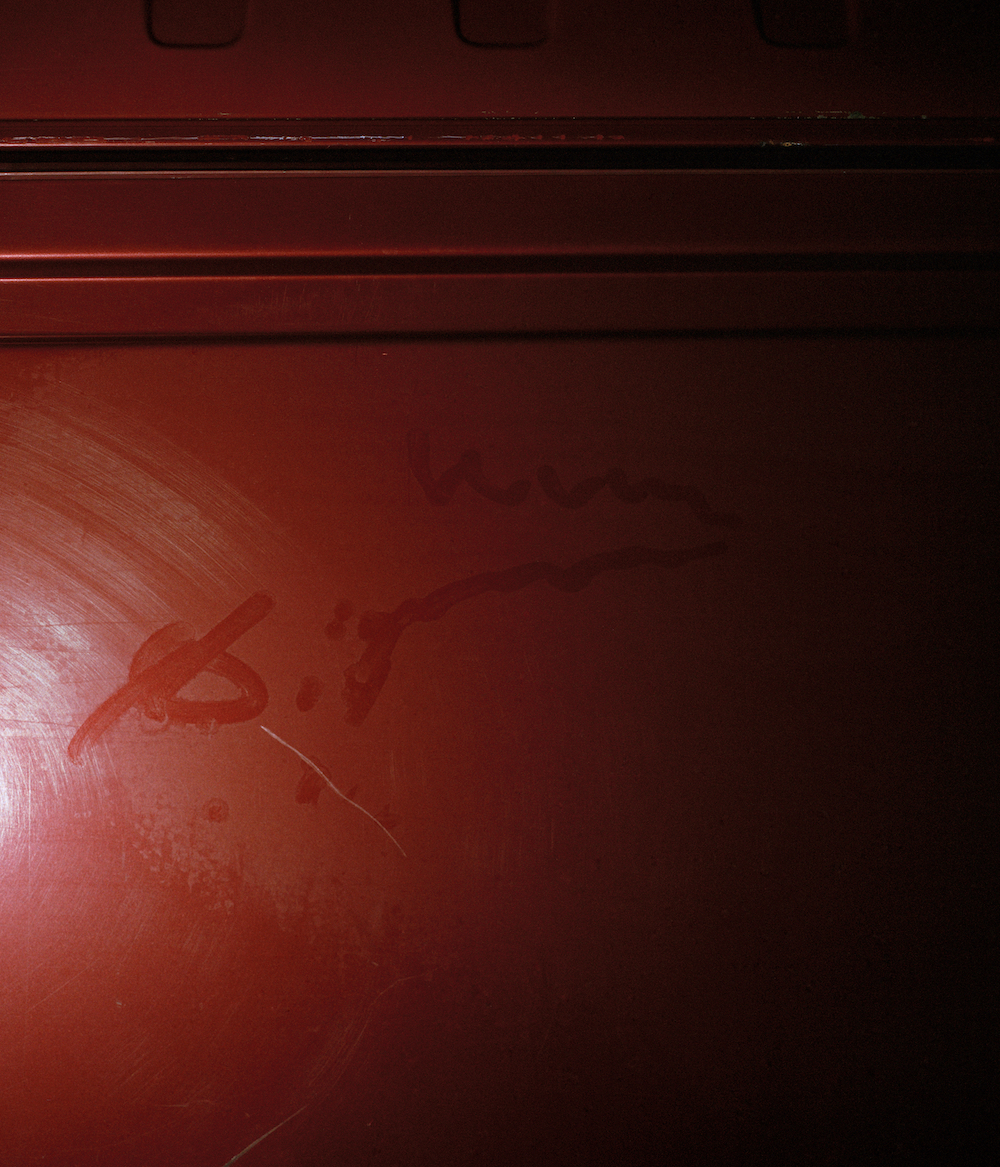

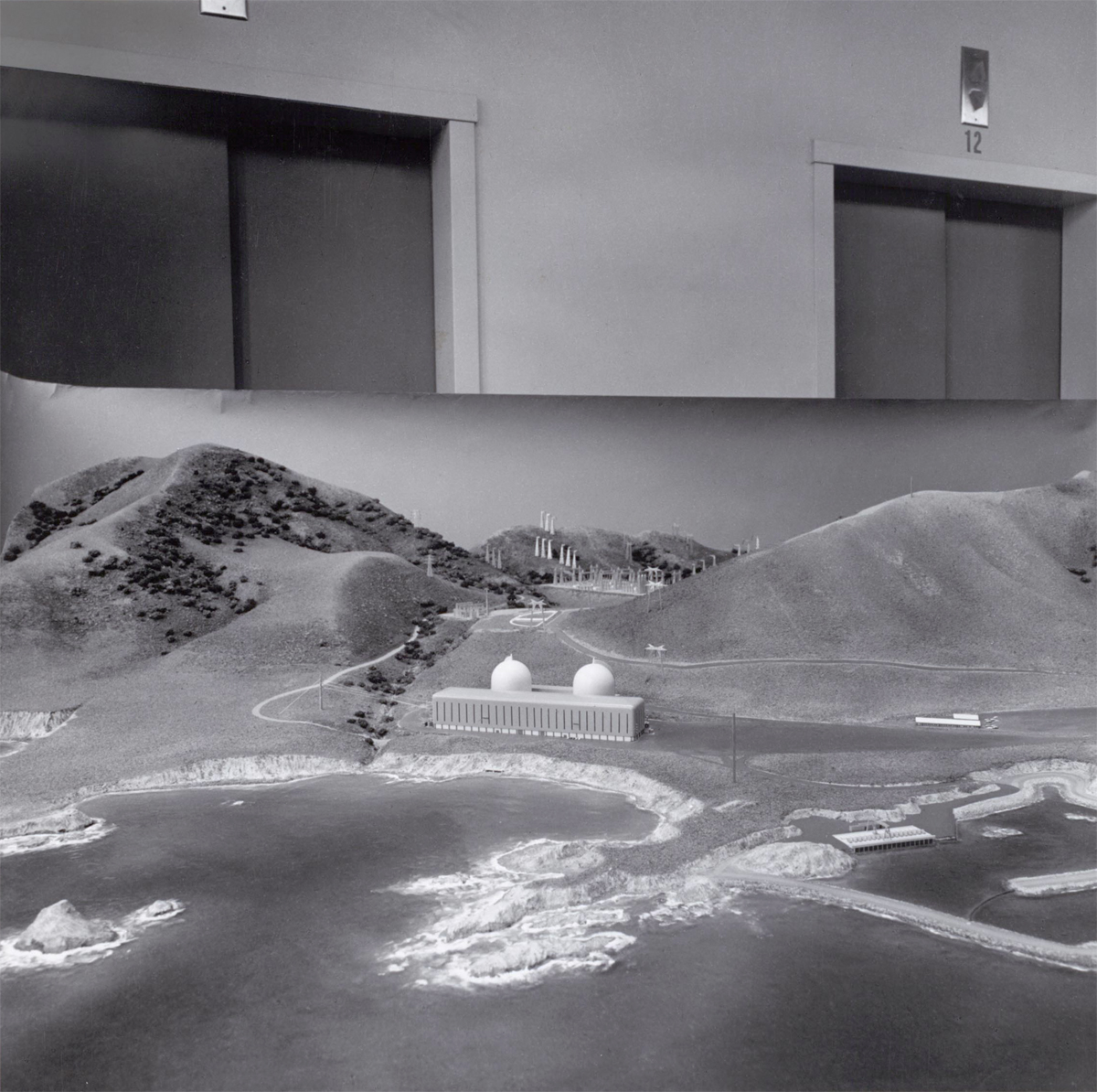

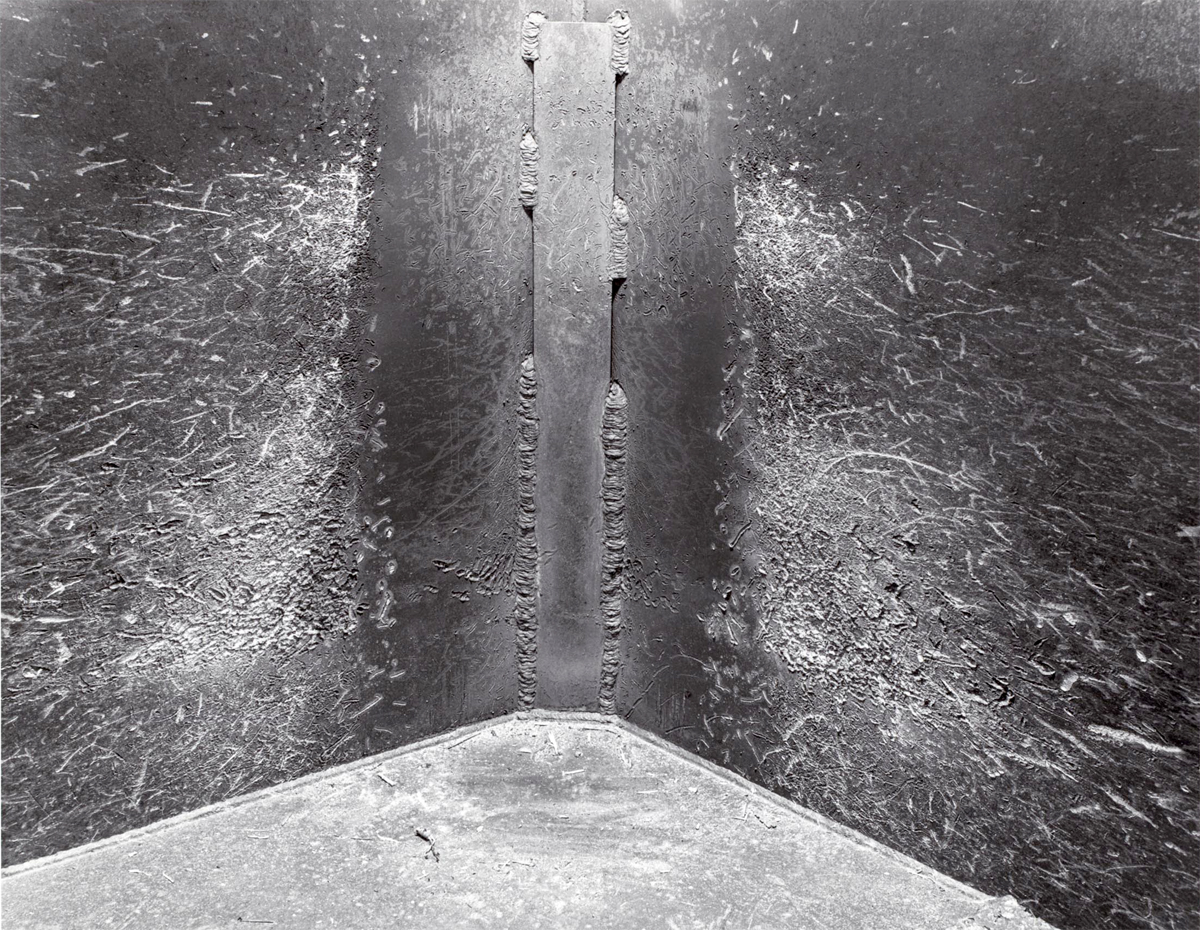

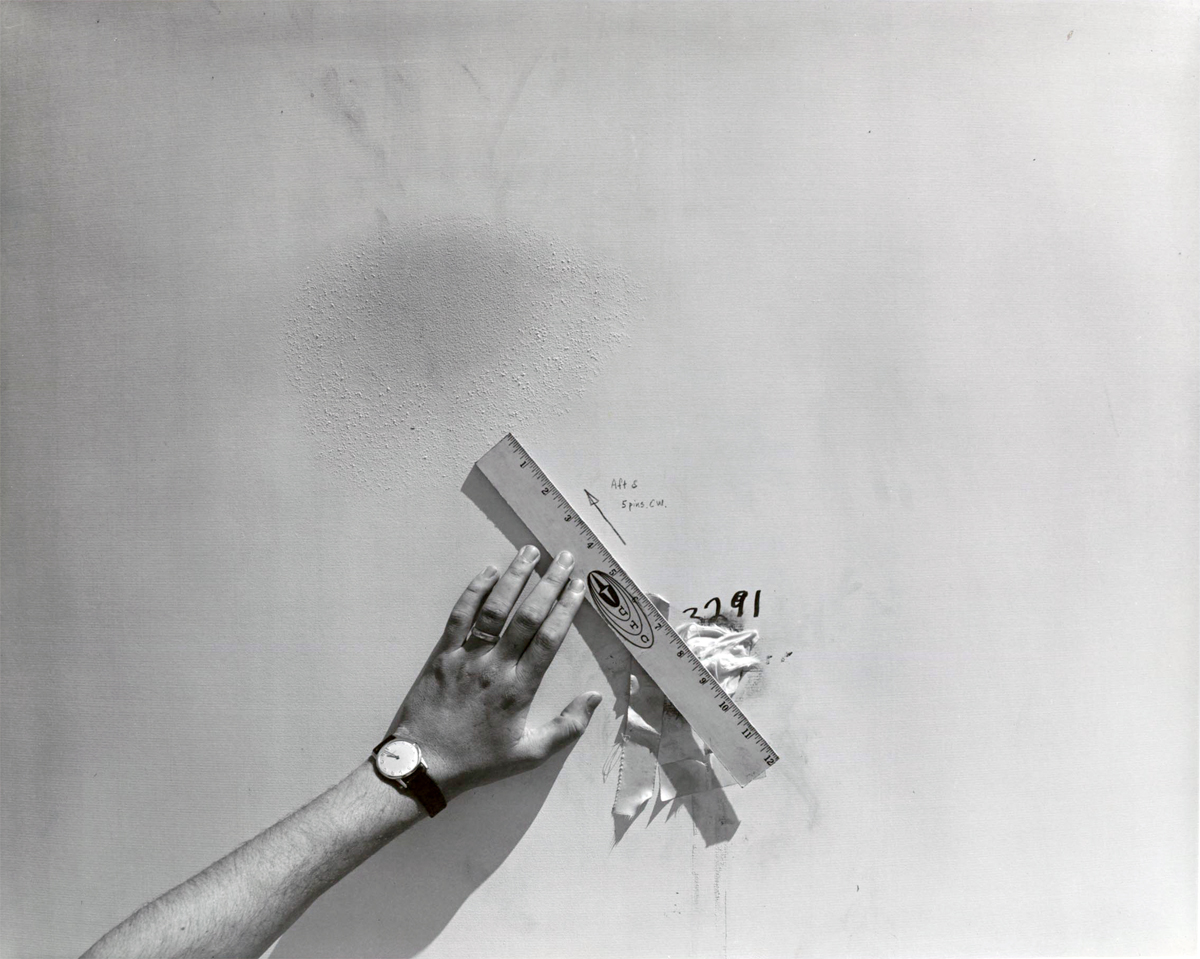

The first conscious work that enlightened me to this exciting potential of photography was the 1977 exhibition and book ’Evidence’, by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel. It’s an extraordinary project wherein the images are all taken from US Institutional archives – government departments, the military, scientific establishments, and law enforcement agencies. These images were made as documents of events and tests, but within the confines of the book the fifty-nine images, selected from thousands, are striped of textual and physical context. In so doing, they are ruthlessly reduced from evidentiary record to aesthetic ambiguity. It’s a task in exposing the fickle nature of the photograph in even the most scientific of settings, and the joy of the book is in the artificial narratives that are conjured in the eyes of the viewer, whose own ambivalence towards the subject matter provides the space for these narratives to form.

‘Evidence’ Images courtesy of Mike Mandel and The Estate of Larry Sultan