Hoda Afshar

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

Noora Sandgren - Fluid Being

Dec 14, 2016

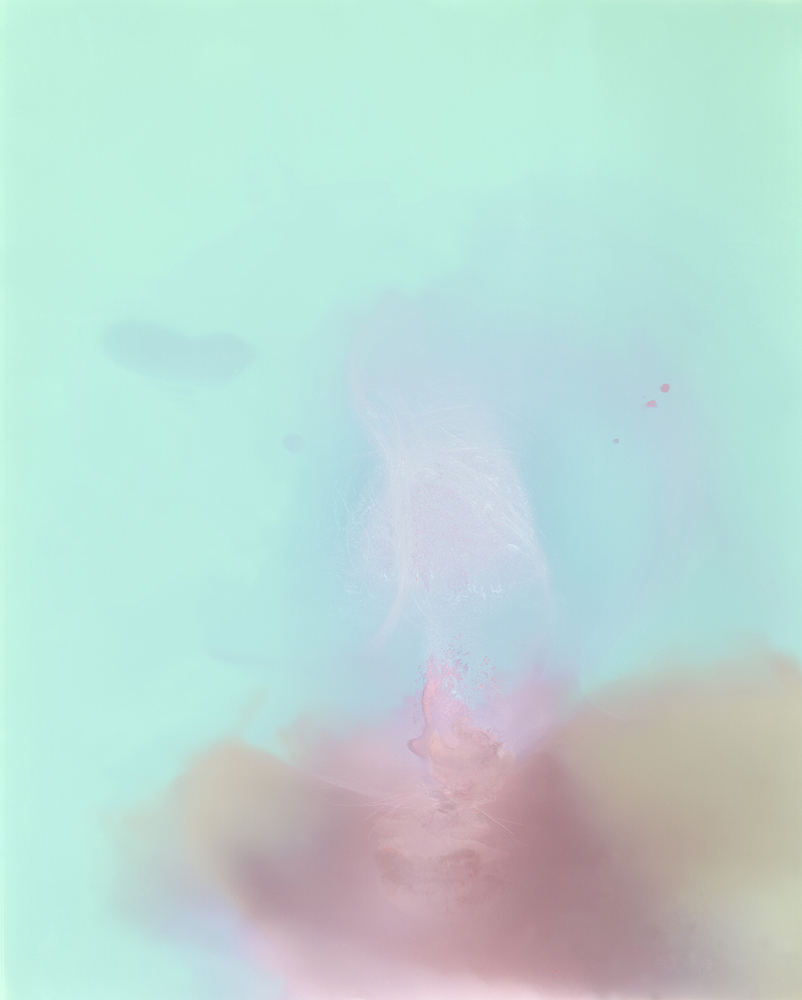

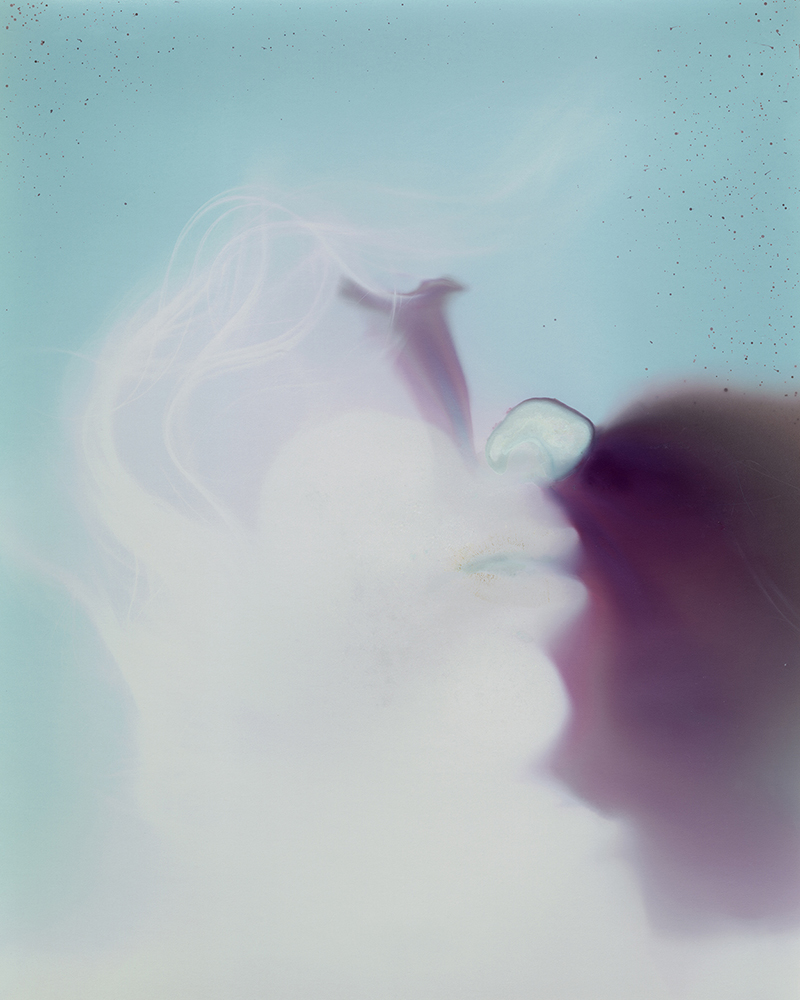

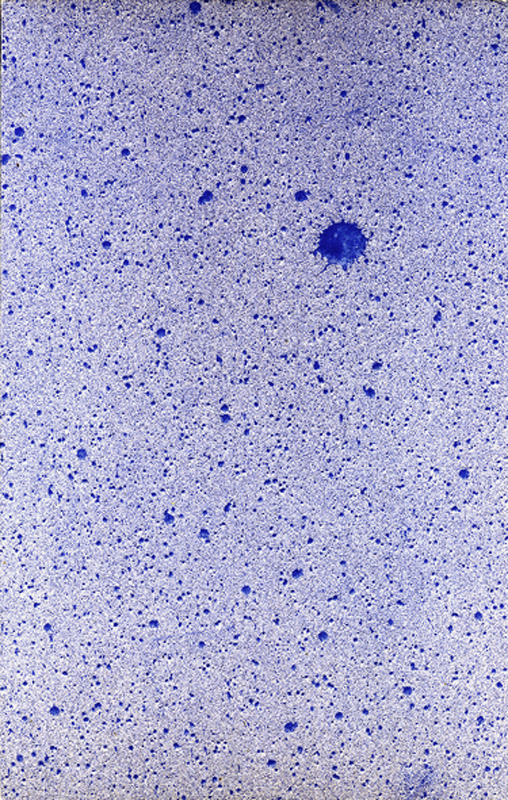

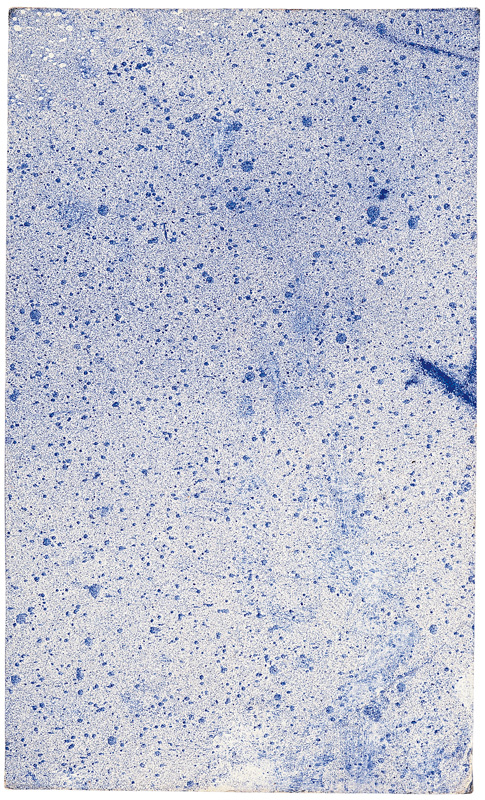

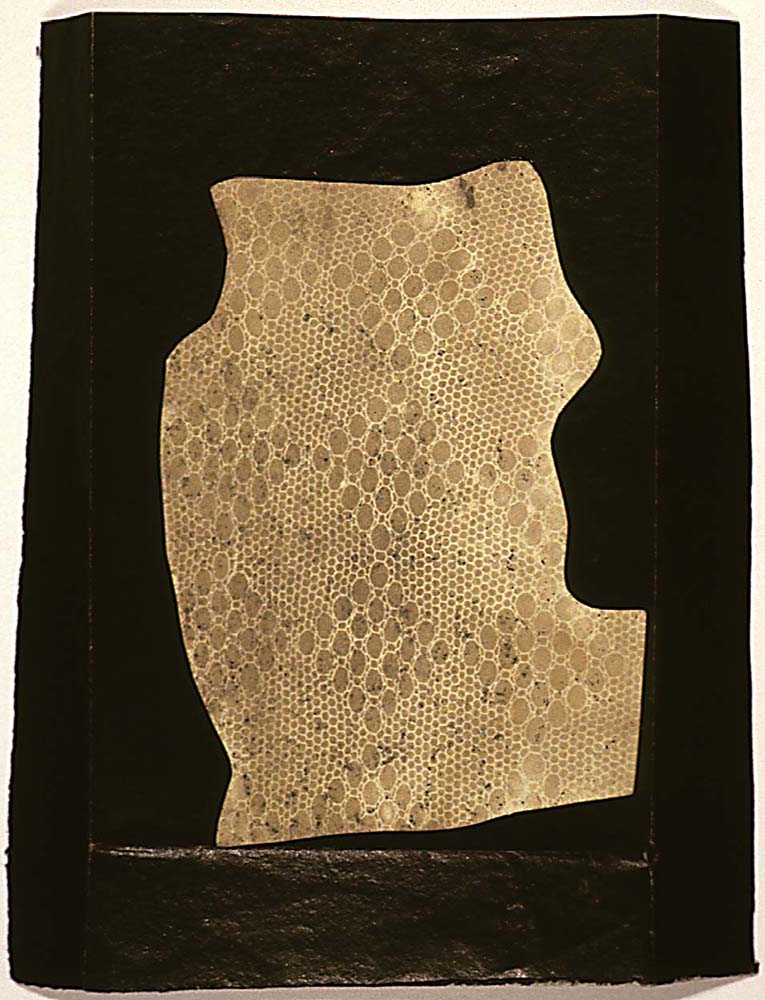

Fluid Being

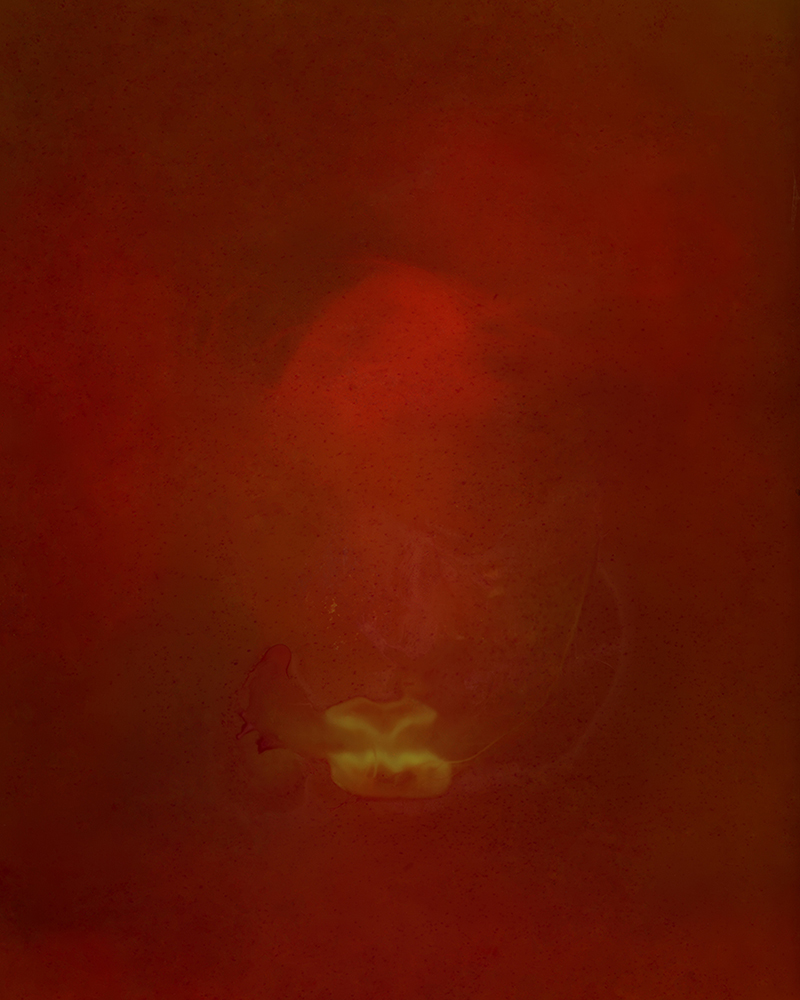

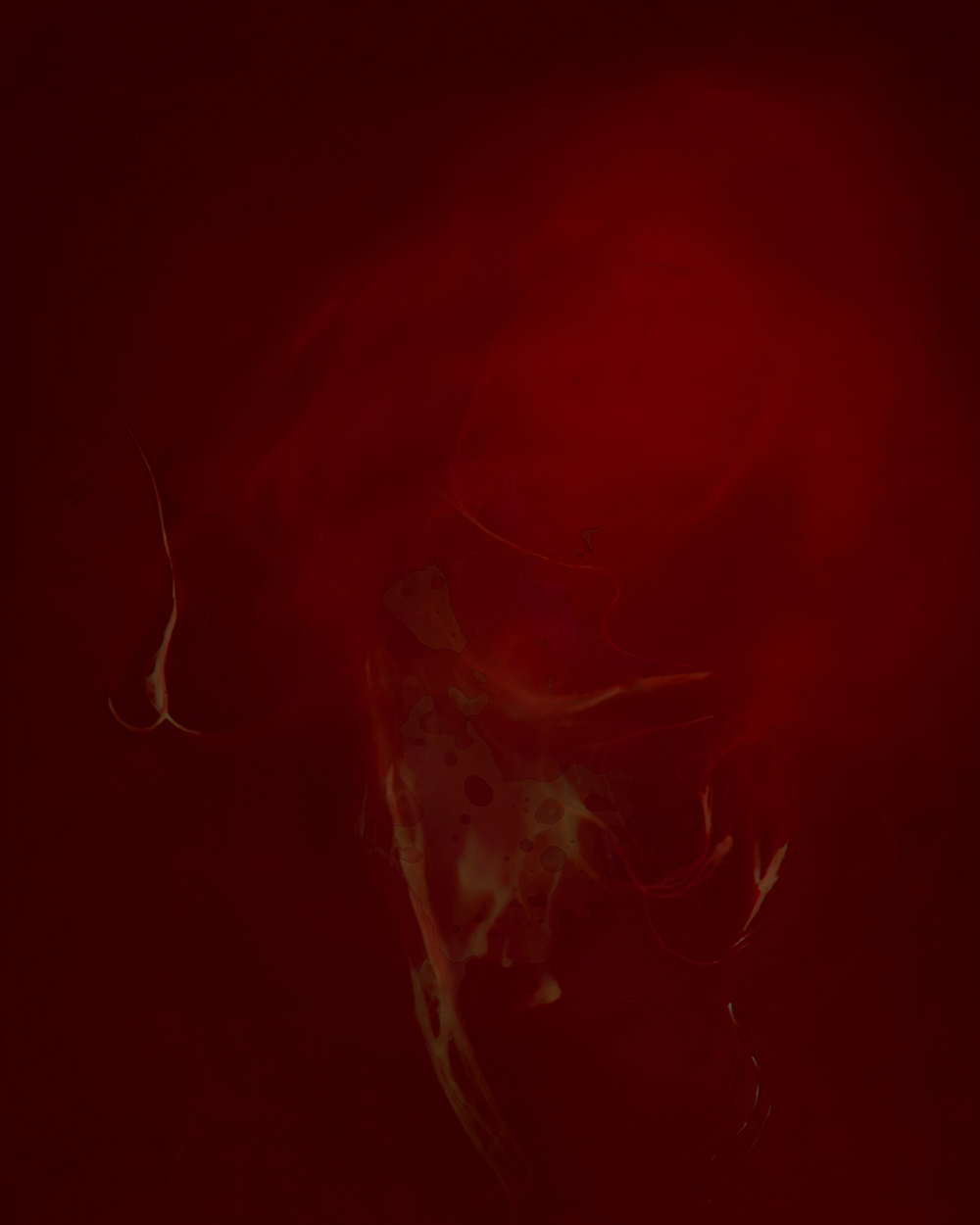

How to capture the wind blowing so hard you´ll get tears in your eyes? Or the sensation of midge biting your chin? Most commonly you’d take a picture of the watery eyes or of the midge just landing on your skin. But these are only distant, external representations of the bodily experiences. These fleeting sensations of being touched by something inhabit the poetic images of Fluid Being by Noora Sandgren. This is a long-term on-going series, which the artist has been working with since 2015.

Garden

The starting point of these photographic works lies in Sandgren´s family garden space. She uses found material – her father’s light sensitive papers from 1970. She pauses to stay still facing directly towards sensitive paper for 30 minutes, letting the natural light, her bodily movements and seasonal conditions around her create these ethereal images.

The scene of the creation of these images – a domestic garden – carries at least two meanings. First of all the garden stands as a basis for a very non-domesticated, open-ended artistic process. The notion of domestic garden has also been perceived as a space for distinct feminine expression and care: vegetal utopia.

The utopian aspect emerges also from the visual grammatology of Sandgren’s images. It resembles Luce Irigaray’s notion of écriture féminine or “writing the body”. The visuality of the Fluid Being disrupts the ‘patriarchal’ control structure and naturalized logic of representation or the composition of a picture plane. These images pertain their mystery. Even the knowledge on Sandgren’s artistic processes and the working conditions in the garden does not fully give reason to these photogram-like works.

Fluid Being is derived from the void: from just being – breathing.

The agency of the multiple

Sandgren’s garden is post human. Even though her images are essentially self-portraits, no identification of a distinct “I” is possible. Neither there is an “other” to name or point out. Artist’s presence is dissolved to surrounding conditions, where all is equal, interdependent and changing.

Sandgren’s way of using the light sensitive paper is all-invitingly hospitable: in the picture plane there is no separation between the non-material and material, human and non-human, natural and artificial – I and You. The Fluid Being is being as one – in flux.

Duration

Marcel Duchamp’s painting Sad Young Man on a Train (1911-12) was a biographical depiction of Duchamp’s melancholic train journey. The whole duration of the journey as well as the motion of the train is simultaneously condensed to one painting. Sandgren’s experimental methods in the Fluid Being follow exactly the same principle.

The duration, the before set slow exposure time of 30 minutes, is the only constant factor in these photographs. All the rest is grounded on the uncertainties: the old light sensitive paper is unreliable, the forces of nature are unforeseeable, the physical reactions of the body are situational, the scanning technology overpowering… These uncertainties are the very forces and wonders of the Fluid Being.

– Riikka Haapalainen, art historian, researcher and lecturer

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Der Greif #9«

The art gravity

Dec 21, 2016 - Noora Sandgren

Adventurous spirit, Bas Jan Ader (1942 – 1975) was a curious one. Being a conceptual performance artist, photographer and filmmaker, he also created audio-video materials, writings and installations making his professional career in 1970s Los Angeles.

In Ader´s performative film “Broken fall (organic)”, he´s hanging from a stubborn tree branch until he looses the grip and falls into the water stream. This takes 1 minute 44 seconds.

In his film “Fall I” he´s sitting on a chair balancing on a roof top, until he falls to the ground. In “Fall II” he´s riding his bike to a canal, falling into the water.

These works have a sense of play that reminds me of childhood – when adventures were always possible, body strengths unlimited.

However when considering Ader´s work more seriously, his concept of studying the aspect of falling contains most essential themes of human life.

The vulnerability of the actor awakens a process of empathy in the viewer. Then, there´s the dimension of distance, seen from the physical and psychological aspect. Many ideas come to mind from the titles too; the opposite of falling is sustaining control an by definition, “fall” implies f.ex. to occur at certain time, to drop in pitch of volume, to suffer ruin, defeat or failure. Interestingly it also means to pass suddenly into a state of body or mind, a new state of condition.

And what about his relationship to natural law of gravity, which he draws into visibility by using his own body. He must have understood that water weakens this law, was that his way of breaking this law just a little bit?

In these performances, there´s waiting, suspension, the temporal and spatial shifts in the action, all of which give clues for meaning making.

But perhaps, it is not the tension of holding, the moment of loosing a grip nor the risks and painful collapsing to the ground surface – but the less dramatic and more invisible moment in between these – the letting go, that I find interesting.

Ader also created a triptych project “In Search of the Miraculous”. The first part of this consisted of an exhibition (1973) with photographs of the artist walking with a flashlight in a dark nightly urban landscape (the human construction). On the surface of the photographs, there´s handwritten lyrics from a song, dealing with aspect of searching.

In Search of the Miraculous -project culminated (1975) in a form of a voyage. The plan was to cross the Atlantic Ocean, landing in Europe. With a choir singing sea shanties at his studio in L.A, Ader set off with his small vessel “Ocean Wave”.

Interested in spiritual aspects, Ader had found the title for this performance from a philosopher P.D Ouspensky´s same named book, which reflected his association with his teacher George Gurdjieff, known for his dynamic system of working with oneself, the Fourth Way (1890-1912). This focuses on reaching towards humanity as part of universe, f.ex through practicing “conscious labour”, meaning presence in actions. The teachings also include the notion of the “art of self-remembering.” This to me seem to propose an assumption of something being forgotten or lost. There´s the need but a also the way to deeper knowledge, which to me resonate as an archaic code, written under our skin.

But for Ader, there´s no way of knowing, whether his voyage was more about searching – or having already found what was needed.

And how was it then to navigate and negotiate with constantly changing powerful element of the sea – and the self?

We are left with imagining what exactly happened during this journey because he never came back from the sea.

There is no real ending to Ader´s last performance piece. The idea of this journey is therefore infinite – in the minds of those who encounter this work.

One can conclude though, that he must have had all possible faith in the importance of leaving the already known grounds.

It is this strategy of “going – towards” (the opposite to avoidance) that I relate to in his work. It´s the beginning of a meaningful dialogue.

Videos & more: basjanader.com

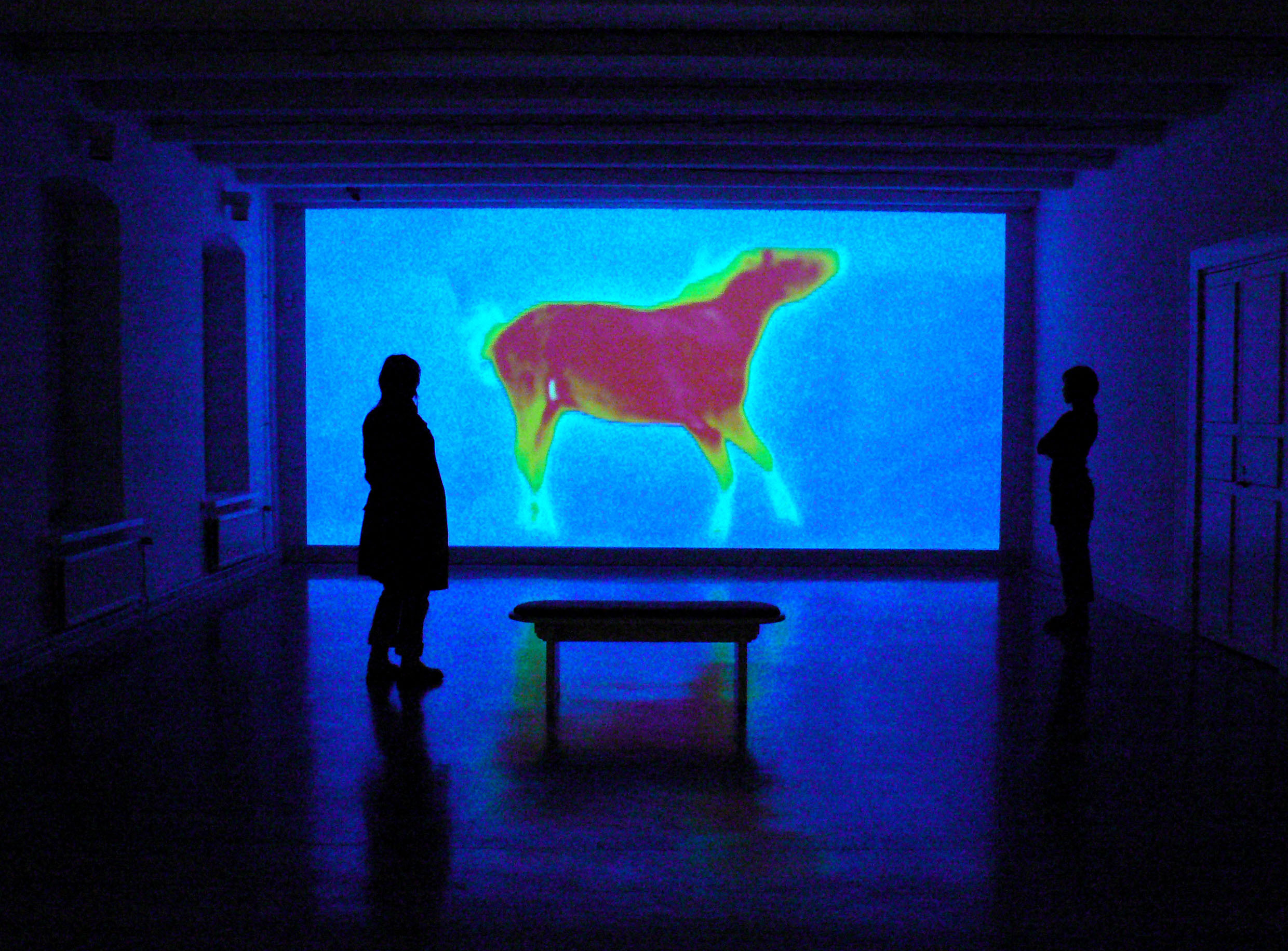

2/6 PIPILOTTI RIST- EYEBALL MASSAGE - HAYWARD GALLERYVideo installations by Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist at the Hayward Gallery in London. Photo by Linda Nylind. 25/09/2011.

Sensing visions, expanding dimensions

Dec 20, 2016 - Noora Sandgren

There is room for more exploration.

When looking for alternative ways to develop the communicative power of art, perhaps it might be about the works becoming real experiences, perceived with all senses. This means creating absorbing spaces that enable one to enter new worlds – that can show ways to re-think reality. Sounds, light and projections to different materials create space just as human bodies create space. Heightened awareness and sensing color is interestingly dealt with in Olafur Eliasson´s and Ma Yansong´s Feelings are facts -installation. Here limited visibility call one to listen to and perceive with ones senses more holistically while orienteering in space, which in turn can be defined as something related to the dialogue between light, boundaries and feelings.

Challenge to media art is saying goodbye to physical user interfaces and focusing to using human body as an interface, using the bodily capabilities and taking the natural sensory system into account.

Where real and virtual environments are merged, also physical – the haptic and digital can interact. An immersive space that reacts directly with human body is an interesting idea in terms of sharing an experience and for the artist giving up of control over the outcome. I am currently exploring within my collaborative projects this kind of space – body installation possibilities related to the idea of sensual experiences. I for example want the garden space I use for creating my art works, become a real stage for contemplative processes and other ways of seeing also within a gallery space.

The technological extension of the imaginary is an interesting thing that among others Pippilotti Rist´s multimedia represents. By using music and large projections of video she transforms the museum spaces into something fantastic – and tactile. By doing so, she also frees the image from its common form. Experiencing her work can give feelings of rest and joy, but behind the beautiful first look, there is more serious dealing with human body, especially the female one. More difficult topics can be taken into observation, when the setting is sensitizing. The immersive environment is in line with the artists aim of creating a space to encounter self and nature, leading to realization of the oneness of all.

Artist, researcher Terike Haapoja looks at this relationship and tensions of co-existence of human and non-human from more critical perspective. Her work involves interdisciplinary cooperations combining art and science. Haapoja´s politically and existentially driven works question our automated ways of thinking of f.ex. the boundaries we make between species, and the inequalities that belong to those categorizations regarding “the other”. Her projects bring out something I find important: the need for empathy, self reflective thinking and how art can communicate this.

Recently in Paris, I got to experience Tino Sehgal´s carte blanche show in Palais de Tokyo, which was a selection of his works merged to one. He calls his art “constructed situations”, meaning his work focuses on social interactions of people. His work reminds me of the idea of social sculpting invented by Joseph Beuys. Sehgal creates these situational interactions by using the human voice – or human as instrument, movement such as jogging, dance and language. His pieces are choreographies brought to life by “interpreters” – and the person participating his show. Without active engagement, there is no way of really experiencing his piece, because meaningful interaction requires parties – in dialogue. This means stepping out of the comfort zone, from conforming with the social norms and roles as we´re used: coming in contact with one´s own fears and hopes.

Sehgal´s work is immaterial, the documentation remaining only in the memory of the participant. This kind of art work is shapeshifting and by nature – liquid.

It is impossible to express in words why walking through a labyrinthine Palais de Tokyo, talking with strangers, was such a powerful experience. The journey started with a question posed directly to me by a small kid, maybe 8-years old. She asked me What is progress?

And nothing less.

Sehgal´s work – the dialogues continue to echo in my mind and body, that weight of the presence… This must have been one of the most touching art-life-experiences in a while. And the echo, it has power, over actions.

See:

Pippilotti Rist´s Pixel Forest show, New Museum, New York, until 15.1.2017

Terike Haapoja artist statement

Olafur Eliasson & Ma Yansong

Collaborating with nature: walking in the clouds with Fujiko Nakaya

Dec 19, 2016 - Noora Sandgren

What does it mean to share an authorship in artistic process? Perhaps it could be described by opening up, inviting chance and willingness to study some other knowledge, language and logic than mine. To actively listen is to let a dialogue evolve by its own weight.

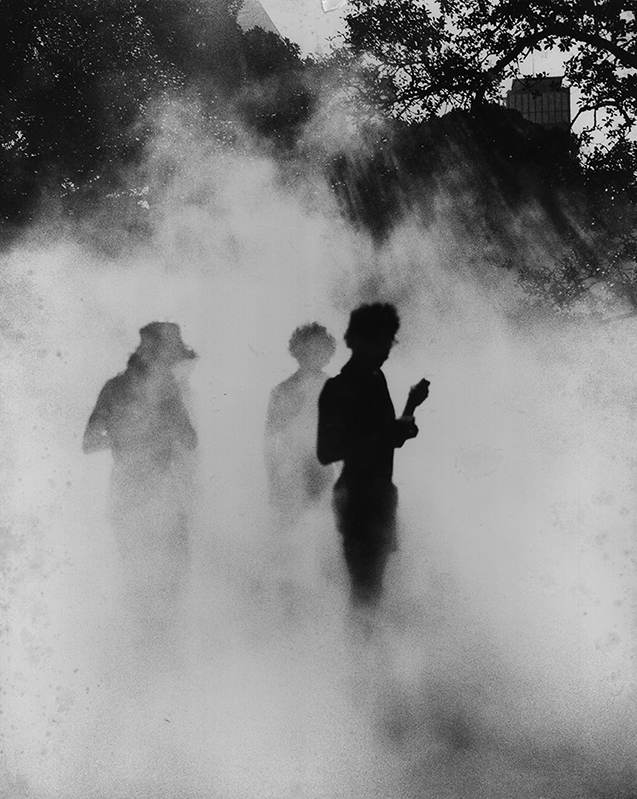

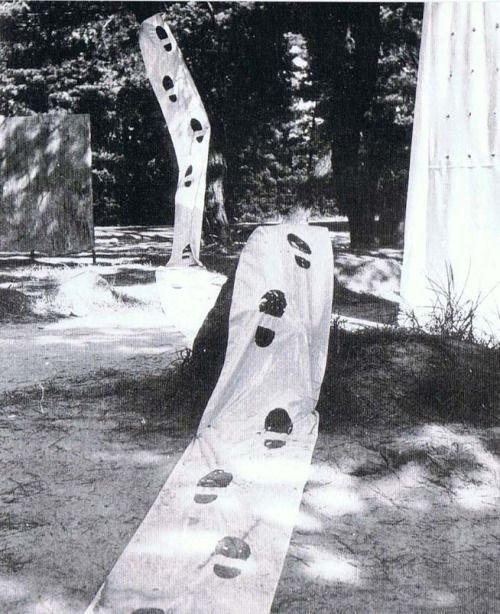

Artists have always been interested in various ways collaborating with their natural environments; Yves Klein let rain create his paintings, however Fujiko Nakayas installation art is a contemporary example of collaborative attitude taken even further. She has been interacting with natural elements like atmosphere, air currents and water since 1970. She uses the fleeting medium of fog to create site specific outdoor sculptures.

The base of Nakayas work with this medium lies in her fascination to cyclical events, meaning process of decay – the constantly occurring phenomena of forming and disappearing. Her fog is a tool for appreciation and access – to get back in touch with nature and being able to interact with one´s surroundings. It seems to me that her using of fog as a medium for sculpting is analogical to photographers using cameras and light sensitive materials – to work with shadow and light in order to draw form out of an environment one lives in and for creating a relationship to space.

The combination of science and art is interesting: long collaboration with atmospheric physicist Thomas Mee was needed to find a technique to generate water vapor mist that could interact with the atmosphere. Testing was required to understand its ways of performing in different weather conditions. For her outdoor site specific installations, Nakaya studies the local meteorological conditions, wind speed and direction also by using her own body in gathering data on spot, feeling the breeze herself.

Nakaya´s fog art is immersive by experience – one walks inside the sculpture feeling the mist on skin. I can imagine it being an experience of joyful play – but there´s also an element of fear. Fog obscures the familiar, it´s a white darkness where one looses the sense of direction, ability to see the way as one is used to. The situation forces one to rely on other senses than eyes, to draw a new path by feeling the way. I think the act of creating a setting or happening like event that celebrates this concealing matter is a strong and even political metaphor. It brings to my mind Derrida´s writings in the Memoirs of the blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins (1993), where a third eye opens up in fingers, when at night one is walking in the darkness. He implies this may be a more accurate way of seeing. I too am constantly questioning the actions of looking and seeing, and part of my works in Fluid Being series could be thought as blind photographs in one sense. Besides the visuals perceived by eyes I am also interested in the action of seeing with fingertips – using body as means to construct a dialogue with surroundings and gaining knowledge by skin.

As ephemeral as the nature of her medium, Nakaya´s fog sculptures exist for a moment, before disappearing. After much of studying she knows how to work with the environment, so that giving form for her sculptures is possible. But she also shows her ability to accept the permanence of change by letting the weather shape her sculptures. More important than permanence of her work, is how her work shows fog sensing its current environment, making it visible. Her works invite one to think how climate changes.

Nakaya´s installations communicate the pure interest of what nature may offer, but also the need for respect towards the existing physical forces, which may not always remain kind.

I relate to Nakaya´s practice of giving up of control over the artwork, which is the magic and releaf in the dialogue with nature. It means the art piece is created from the being-with and negotiating between the human and nature´s will (which is also the politics of gardening), where cyclicality is actually experienced and nothing is solid.

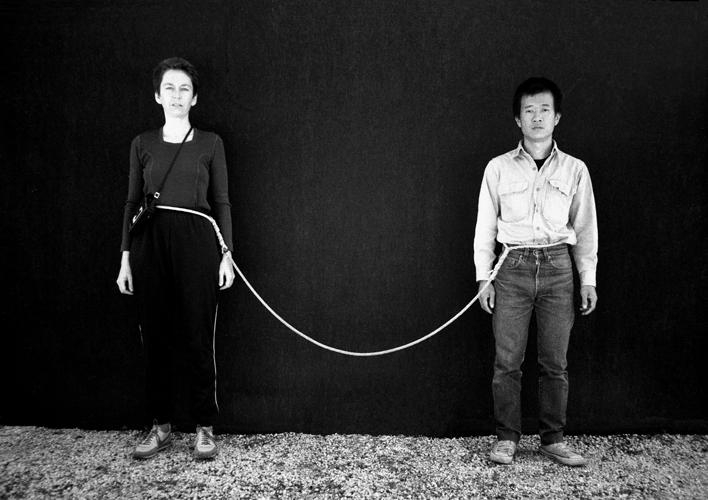

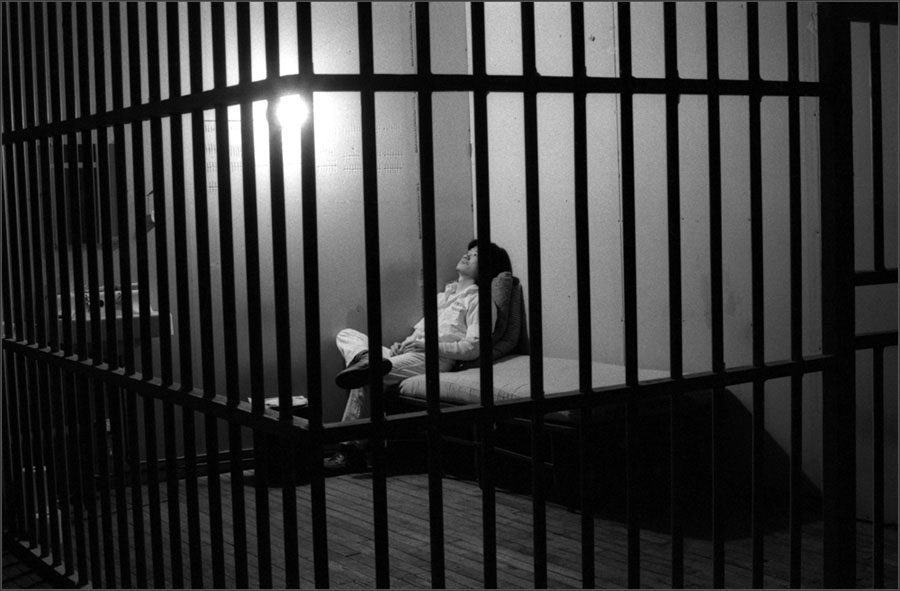

On duration: Tehching Hsieh

Dec 18, 2016 - Noora Sandgren

We often think of time as defined by the pace of actions, results, travels, movement. Being fast or just in right time seems to measure goodness according to social expectations. But can time be measured by clock? Could duration be defined by the experience, of being free?

Tehching Hsieh´s long and radical performances compress the fundamental questions of human life and the politics of passing time. The stage of his performances is life at its barest. The slowness of his processes is intriguing considering he has created these mostly in the fast city of New York where he came as Taiwanese immigrant. His works refer to self-reflection and demand participation from anyone studying his works – a demand for empathy by creating inner images of the process, which lead to many questions immediately recognized as important ones – not to be dismissed.

He was 28 when creating first One-year performance 1978-1979, the Cage Piece. During this he stayed in solitude in a cage he built himself, without communicative devices, or talking, but just being there. The trace of those days is a daily photograph of the artist and a mark scratched by fingernails on the wall. Thoughts rise to my mind on the human capability of either restricting or freeing one´s mind.

In the One-year performance 1980-81, the Time Clock Piece he punched a time clock every hour, 24-hours, year round. He let his hair grow over the year, and each clock-punching moment was documented by camera resulting to one day compressed into a second, and the year into six minutes. Year as a unit is the time earth moves around the sun as well as the human calculation of time. In this piece there is the philosophical idea of being in time, contrasted to the way our time is often measured by time spent, often dealing with work and effectiveness. Here the artist´s actions seem meaningless and repetitive ”but every time the hour is changing, it´s very different.” he says. This makes sense to me.

Third One-year performance 1981-82, the Outdoor Piece consisted of Hsieh spending the year outside wandering, without entering human constructed spaces. Being homeless makes one fall out of social status categories and lose much of control over one´s life. The basic survival aspect interests me, because it brings human life closer to the goal of all living beings.

In fourth one; Art/life, One-year performance 1983-1984, the Rope Piece, Hsieh collaborated with Linda Montano, tied to her by 2,4 m. rope, but not touching. Unknown to each other they´d now be closely connected. This brings to mind the fact of always being tied to each other, as strangers, and tension created by the individuals struggle for freedom. For the last performance Tehching Hsieh 1986-1999, he disappeared for 13 years, stating to make art and not show it to anyone. Only documentation of this being a text piece by the ending saying “I kept myself alive. Passed the Dec 31, 1999.” Here freedom, art and life are all one.

Hsieh´s work value the essence of being. It makes me wonder how and by whom time can be valued, rated or measured?

Those mental images I as the viewer of Hsieh processes have by now imagined are strong. Between these, I can find a glimpse of my own truth – which is more than many of the photographs aiming to convey truth are capable of. In my own process the engagement in repetitive actions over the years to come create a sense of sustainability – a ground to cultivate knowledge. I consider time as a varying experience, connected to slowness and I´m interested in the uneasiness of acceptance of time. With my cameraless process, the originals continue to develop, time will do its work. Much about photography attempts to stop and control time. However the experience of passing time may be more important. After all, time can not be stopped.

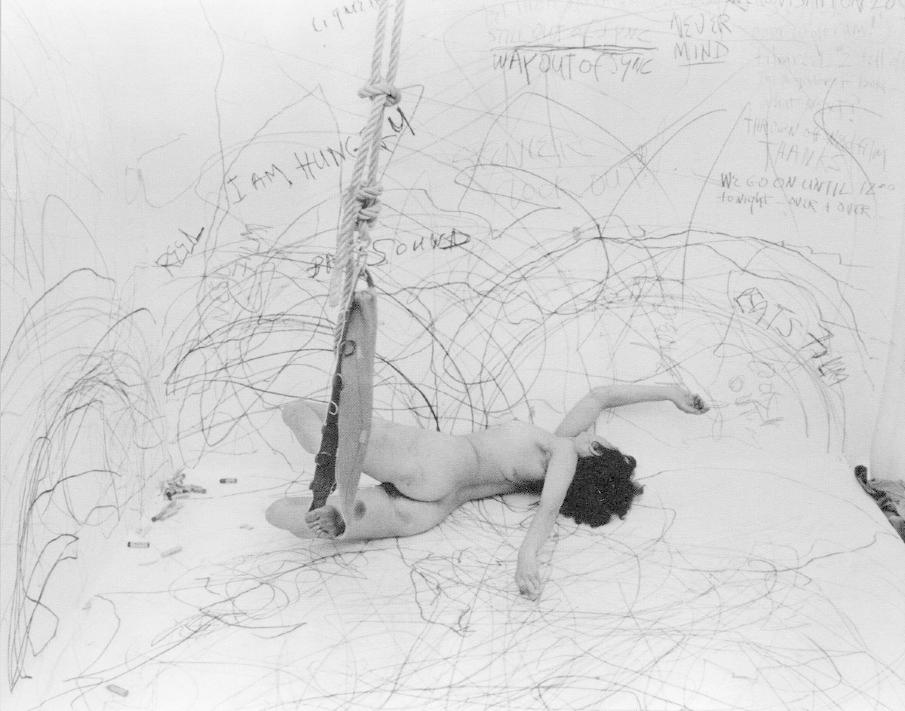

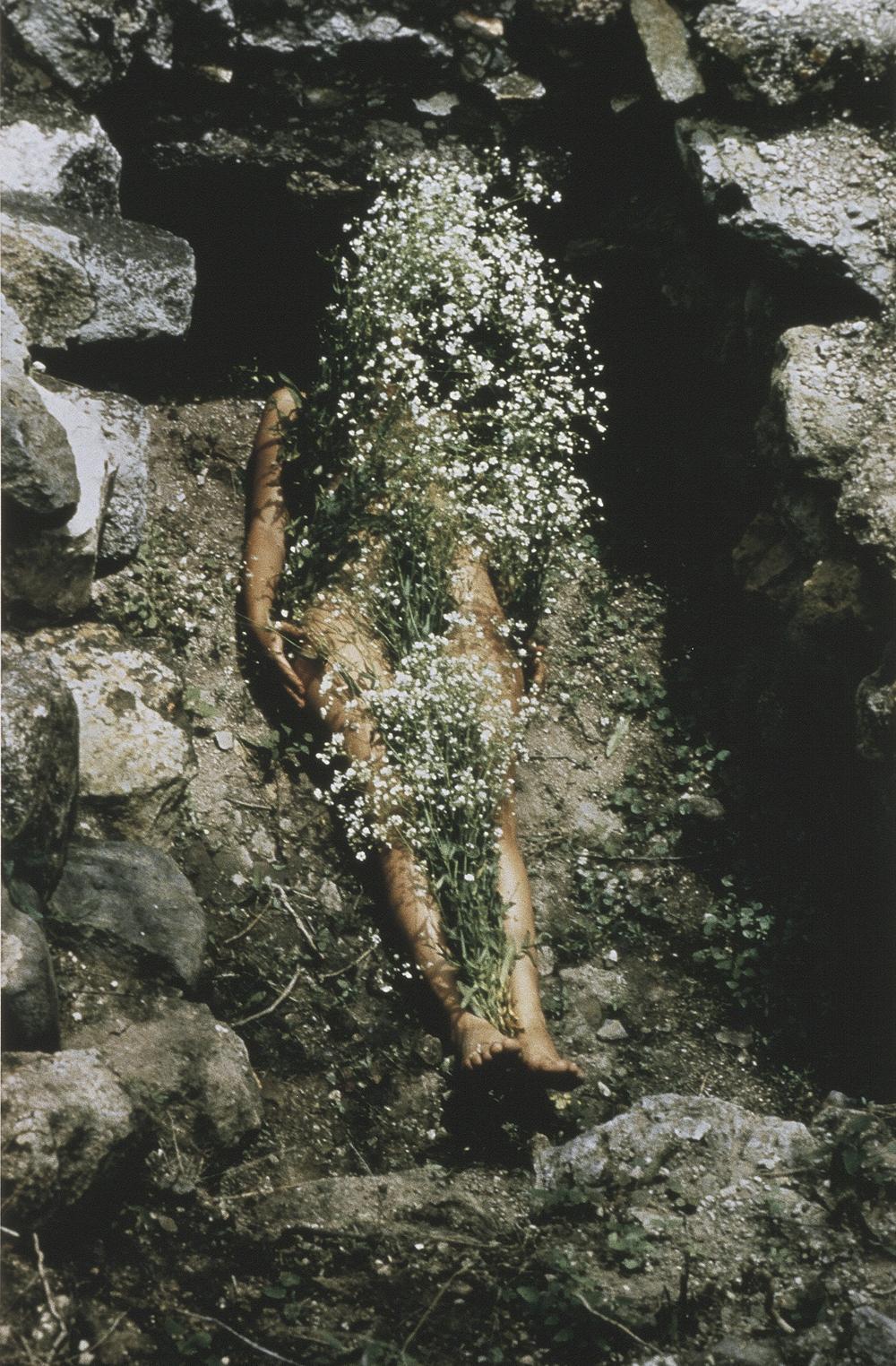

Body – material – space

Dec 17, 2016 - Noora Sandgren

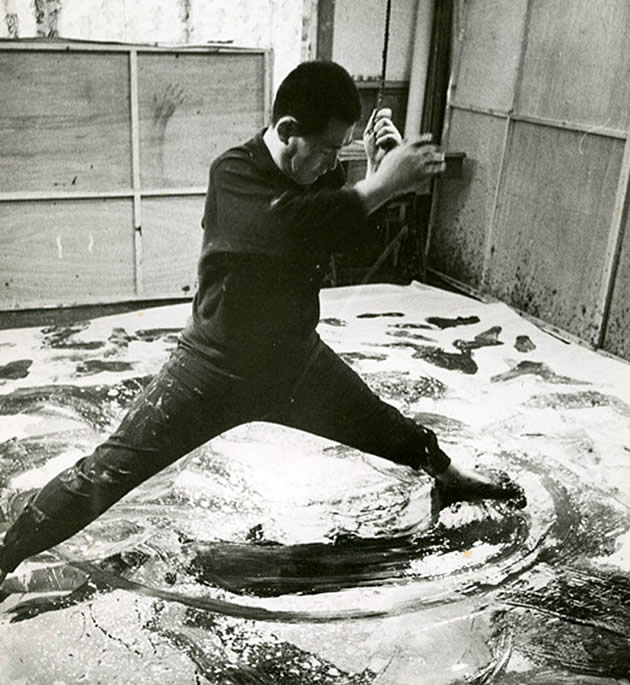

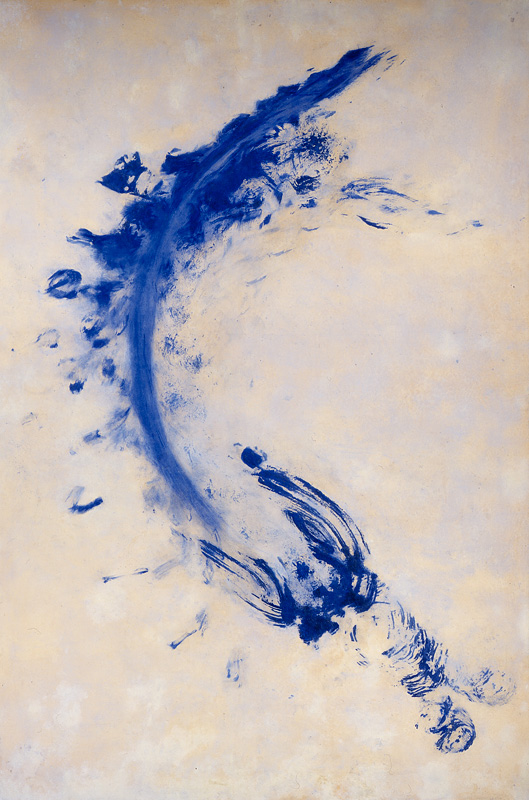

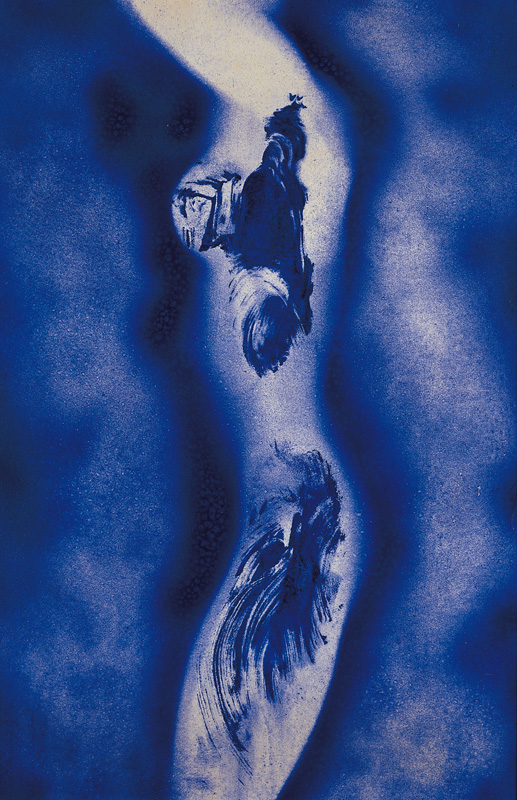

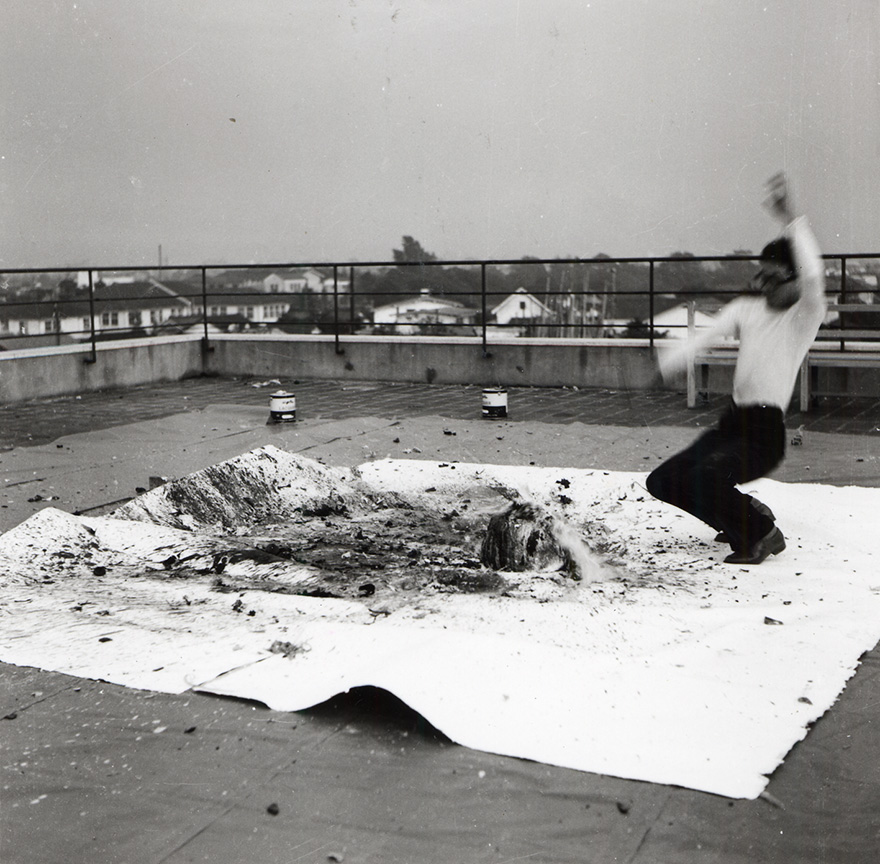

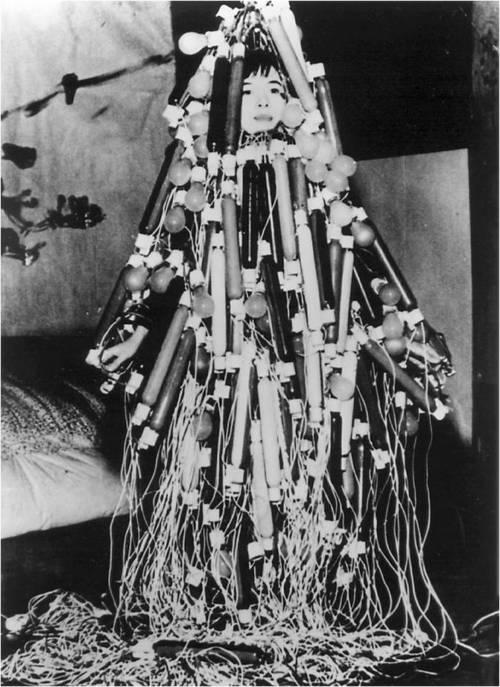

Breaking conventions were at the core of the artistic processes by the avant-garde artists of postwar era – when the modernist promises of progress had collapsed and the destruction seen. Japanese Gutai group (1954-1972) organized by Jiro Yoshihara refer by name to “concrete” or “embodiment” as means to address reality. This was less about representation and more about manifestation. Their attitude was experimental in search of freedom, artworks took forms of: performances, films, including environments and objects. Everyday materials were used and their Manifesto declared “Gutai Art does not change the material but brings it to life.”

This meant listening to its characteristics. It resonates with my relationship to material as well; confronting and researching it with all senses and understanding that all materials have a nature of their own. This is an attitude of openness to chance and risk. It´ s about closeness instead of distance, warmth and tangibility instead of simply looking through a device that often stand between the artist and reality – mediating with its own predetermined operations. It ´s about self generated embodied knowledge, by intimate interaction and by challenging self.

Shimamoto Shozo´s action based paintings were created by the forceful throwing of paint bottles exploding on the canvas caused by the impact. In Kazuo Shiraga’s politically and ethically charged performance Challenging Mud (1955) he was stripped from nearly all clothes, confronting the hard material of mud and rocks and working with it in a rather violent manner in order to challenge himself. His movements lead to a sculpture – a painting composition, which was left as it was for the duration of the show.

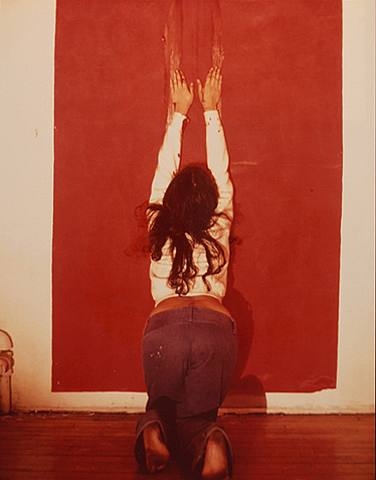

Body as a a living brush in Yves Klein´s performance Anthropométries de l’époque bleue (1960), remind me of archaic human imagery. In this performance models created paintings according to artist directions by pressing their painted bodies directly on the canvas.

The rise of feminism in 1970s, influenced important body and performance artists such as Ana Mendieta and Carolee Schneeman. Also Janine Antoni made her response to Klein´s Antropometries, using her own body as main artistic tool. She´d be both the model and the master of her own marks. In her performance piece Loving Care (1993) she used her hair hair dipped in dye color, and by this action, claimed over the given space by painting it with her hair as a brush. In this piece, she´s dealing with power dynamics related to everyday spaces, turning an ordinary action like mopping the floor into a symbolically powerful work of art. The piece is demanding, it requires difficult but meaningful body positions. The act of taking over the space – namely the floor – by marking it, is an action of gaining power. To me her work resonates as contemporary; care and compassion are strong tools in moving forward. And these are a matter of decisive simple practice.

Latest dialogues

Dec 16, 2016 - Noora Sandgren

October cloud weather, the in-between-season.

A travel from the city of Helsinki, to countryside garden space in Hiidenvesi.

This is a space for inside – outside interaction.

Over 30 minutes, with an active paper space, a frame

Ilford orthose large format film, older than me, found material that used to belong to my father.

I am here, sitting still

breathing with this sensitive material. And the garden.

The coldness and humidity of the air

flowing slowly inside my jacket, with a persistent direction.

Starting from the neck

moving on the surface of my skin

diving under, slowly towards the core.

Chills running and playing, moving my body like an instrument

I am part of a composition.

The garden time, sensed first slow then fast, and rhythms.

Nothing happening – everything happening.

Sense of metamorphose, sounding

then sounds between the sounds open up

forms and rhythms become visible to ears.

I can hear my father digging a hole to already stiff ground, organizing a living space for a new berry bush

Eyes open, I can see the chemistry of the film traveling on its surface, forced from its place by my saliva – that digestive agent.

This might be a painting then

But it will remain mostly invisible. Sometimes taking weeks, or months, until the second exposure – the time of the scanner. The slowly moving light sculpting this vulnerable image with its own ways – simultaneously destroying and bringing alive and visible the result of the dialogue in garden.

Then a closer readings on László Moholy-Nagy. He was experimenting and researching in late 1922, using fluids like water on his photo paper which would result in abstract pictures he called photograms. Couple of years later he´d create a theoretical base: “New Vision”, stating that light ought to be handled like the colour in painting and sound in music. To him too, the medium seem to have been more of a tool for meaningful interactions with the world, and not an end.

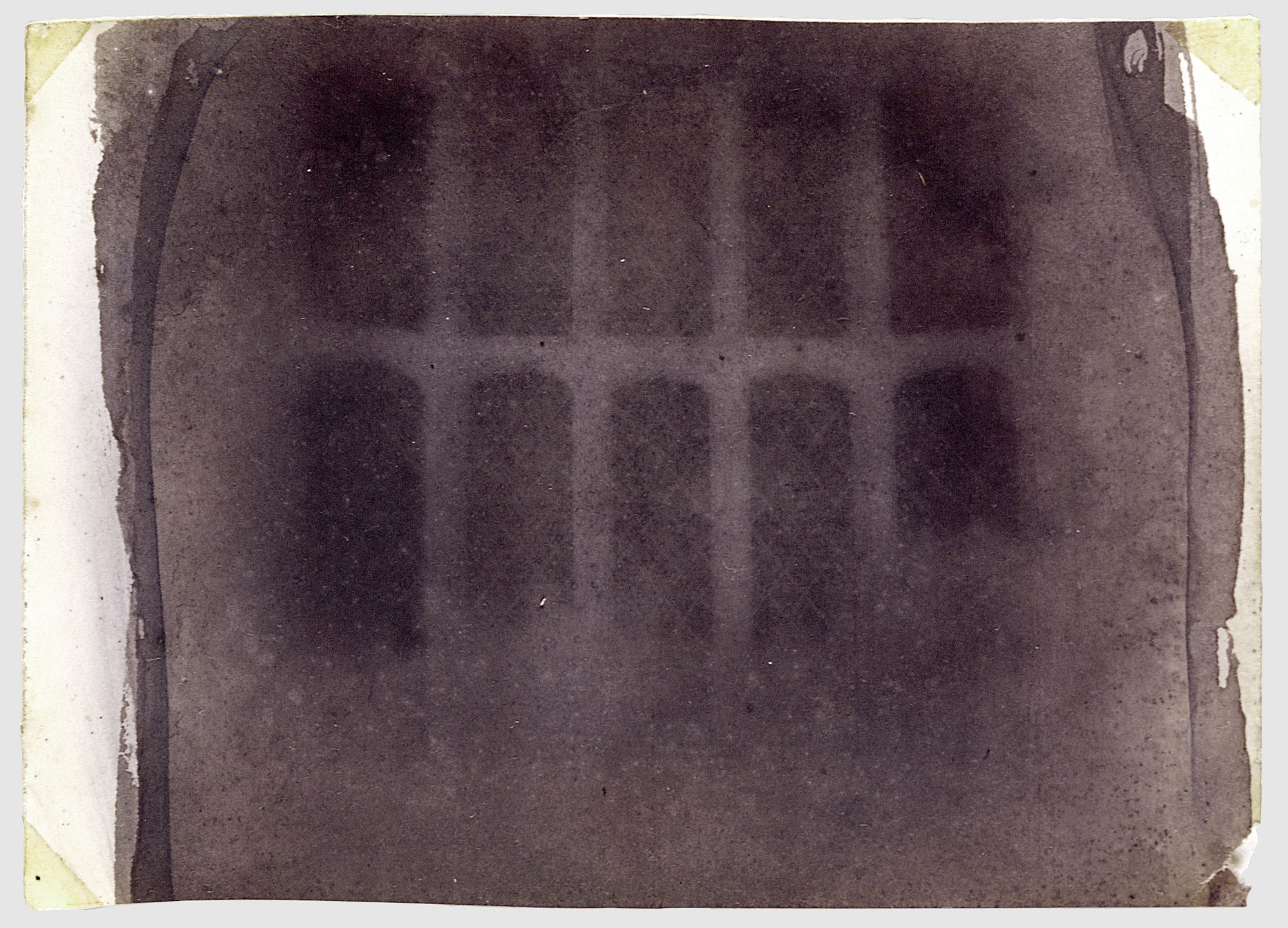

Basic elements

Dec 15, 2016 - Noora Sandgren

The urge to create a trace and the nature as a generative force has always been there since the first human made images, also in beginning of photography. In 1833 a curious mind, interested in e.g. astronomy, botany, philosophy, chemistry – William Henry Fox Talbot (inventor of negative-positive process), started to wonder about the transformative ability of sun light. His experiments grew out of interest but also frustration: he felt he could not draw a satisfying image of a great landscape with the help of camera lucida.

First experiments were done by placing a lace or plant directly on the salt and silver nitrate coated paper and exposing it to sun. He could see the sun-drawing the shape of an object on paper – creating a ghostly trace. Soon he discovered how to slow down the disappearance of these shadow images, creating a negative. These sun-pictures he called “photogenic drawings”, admiring the Nature creating its own image, better than the most skilful artist would be capable of.

Fascinated by Talbot´ s primal photography, the notion of Nature as drawing agent, I use for my on-going Fluid Being -series a familiar garden space as my studio throughout the year, working mostly cameraless, reducing photography to its basic elements: chemistry of a sensitive surface, light and time. Like Talbot´s first images, the originals of this series remain unfixed – alive, in a protective black box. This notion of an image, as something living, is important to me, whether understood physically (materiality), or as a viewing process – projective and non-solid by nature.

Interestingly, Professor of the History of Photography and Contemporary Art Geoffrey Batchen concludes on the photography as politically charged field:

“…throughout photography´s history the cameraless photograph has always been a subversive element, an auto-critique of everything that photography is supposed to represent. For in rejecting the camera, such photographs also reject humanist perspective, rationalised space, three-dimensional illusion, documentary truth, temporal fixity. They bring the margin into the centre to confuse precisely that familiar, comforting distinction, and with it a lot of other distinctions, too” (Batchen: Emanations, The Art of the Cameraless Photograph 2016, p.47)