Keegan Grandbois

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

Peter Watkins - The Unforgetting

May 27, 2015

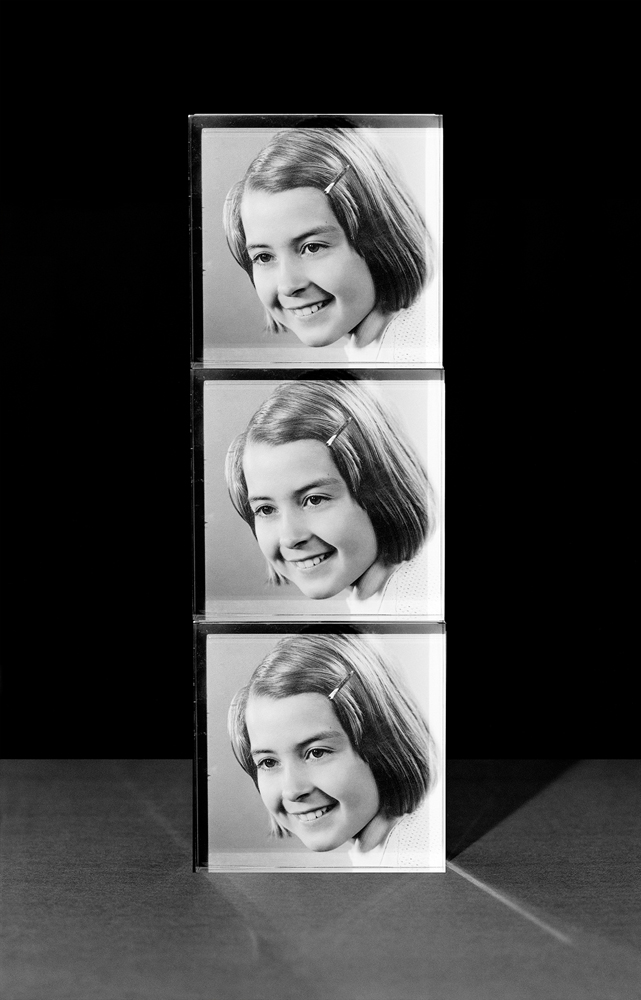

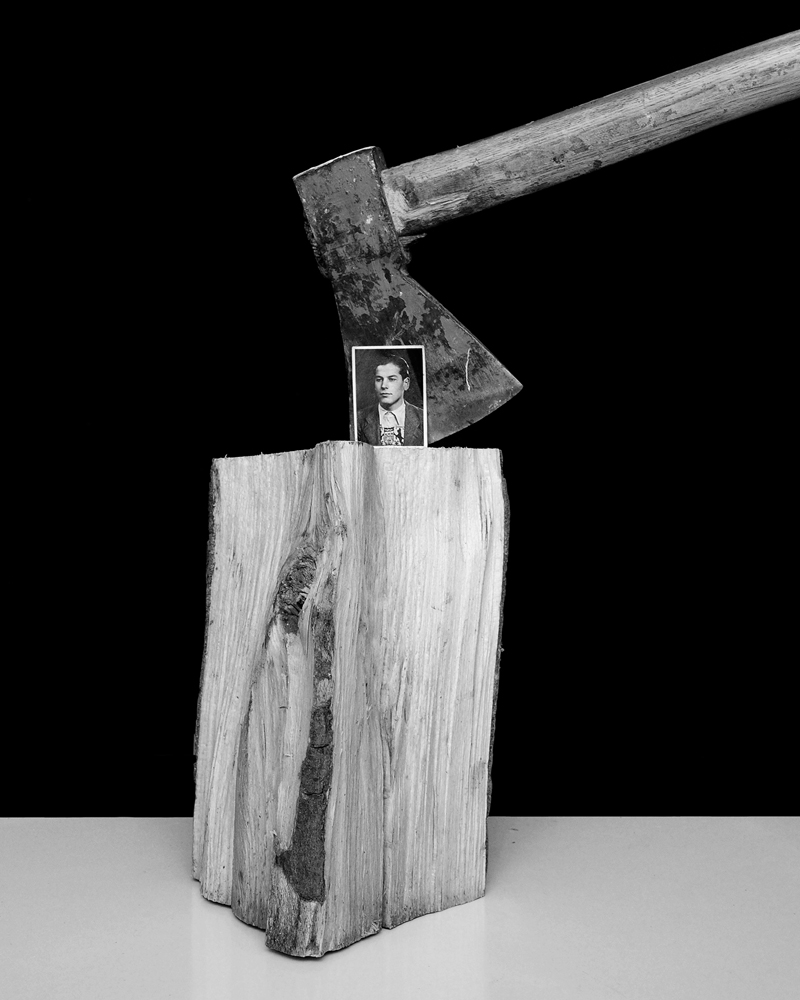

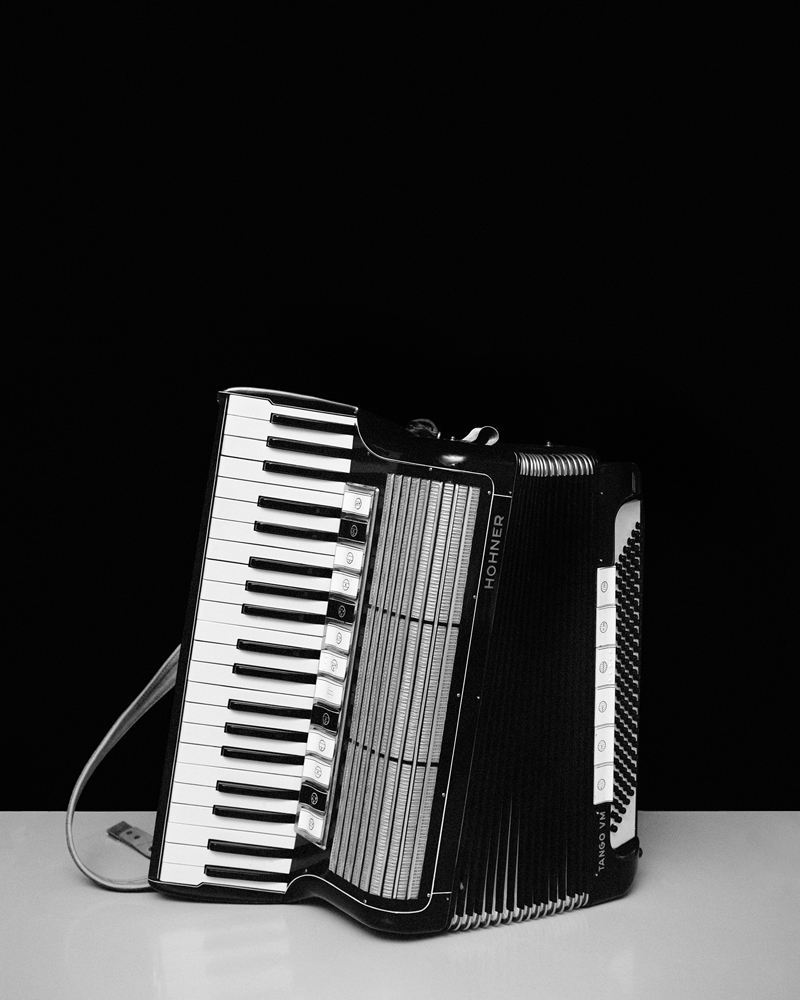

'I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting but rather its lining.' - Chris Marker On the 15th of February 1993, my mother walked from Zandvoort beach into the North Sea to her death. The Unforgetting is a series of works that explores the texture of personal memory, and is told through photography and sculpture, and is presented in installation form. It is a series of works made up of remnants, exploring the loss of my mother, and our shared German ancestry. Often borrowing from the language of museum presentation, these works explore the complexities of memory in the (re)presentation of personal narratives. How much of a person remains in the objects that are left behind, and what can these objects tell us of the trauma of loss, and of how memory so easily turns to narrative. The presentation of objects carry the weight of a family history, but the personal charge with which the images are made remains undisclosed and often obscured, encouraging a dialogue between the universal and the highly personal—images of cans of Super 8 withhold the images they contain; ceremonial glasses appear transparent and emptied of liquid; and a spectral baptismal dress appears impossibly suspended, glazed behind yellow glass: a wash of colour in an otherwise monochromatic series of works. The recurrence of wood throughout points towards the exploration of a certain rural Germanicity; but wood here also represents the passing of time, and of the “here I was born, and there I died,” as Hitchcock’s Proustian Madelaine exclaims in Vertigo, when pointing to the sawn sequoia tree. These works are universal in their stoic unwillingness to disclose their deeply personal roots; but woven beneath their surfaces are the stories and narratives that come to constitute the biography of the departed. This series finds its core, therefore, in the interplay between presences and absences—the absence of the mother, and the traces of her life explored in states of Unforgetting.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Guest-Room Bruno Ceschel«

»Der Greif #8«

The Dream Life of Debris pt. 2

Jun 03, 2015 - Peter Watkins

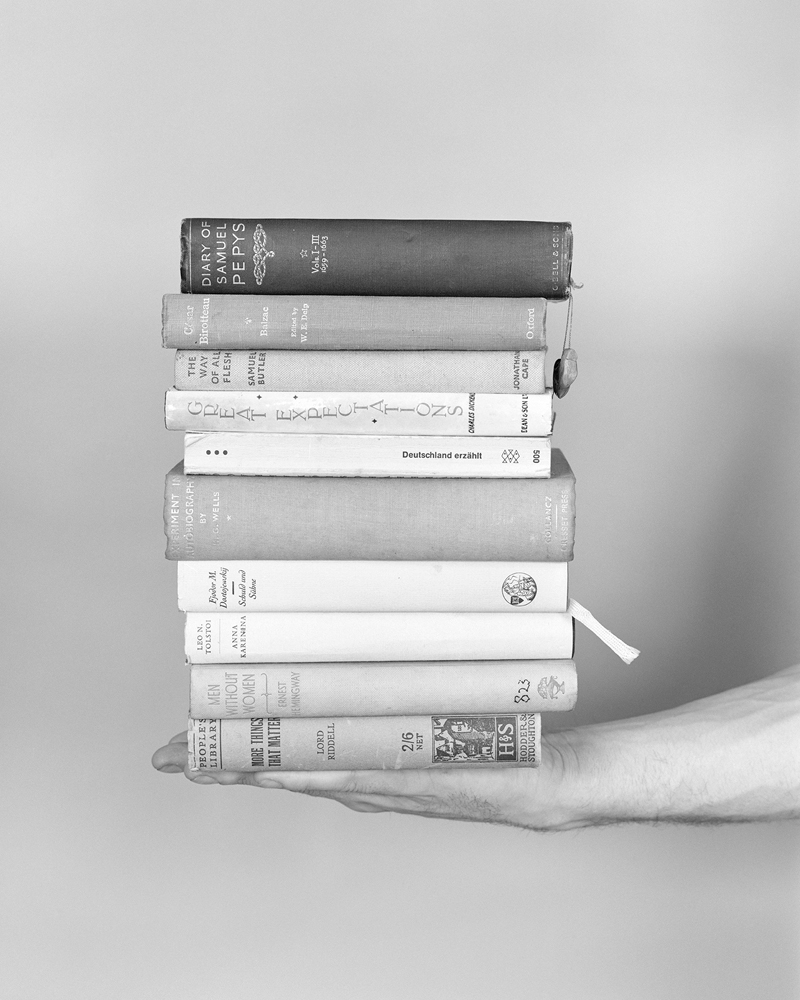

href="https://dergreif-online.de/www/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/07_Sebald-1024x7681.jpg"> There is a single photograph of the character of Austerlitz as a young pageboy, which adorns the cover of the book itself—it is the only photograph of Austerlitz, and he is presented to us as a child, costumed from another time. This presentation of the Austerlitz as his former, forgotten self, prescribes how his identity must be defined in the context of his relationship to his parents—both for us as reader and participant, and for Austerlitz himself. In the photograph he stands defiantly, in a fog-filled landscape, staring steelily at the camera: It is an adult’s gaze, an adult’s posture, as if the older, wiser Austerlitz were embodied in the eyes of his former, childhood self. There are only a handful of photographs depicting human subjects on the pages of Austerlitz, and of these photographs, even fewer maintain what Roland Barthes referred to as “the frontal pose [...] of looking me straight in the eye.” For Barthes, the gaze of the subject (the Spectrum) toward the eye of the camera is the ultimate affirmation of the photograph’s noeme (what differentiates the photograph from other, non-photographic images), from the point of view of the Spectator (the viewer). This single photograph of a boy looking straight down the lens of the camera and directly at us, the viewer, as we learn from an interview with Sebald, is the foundations where upon the entire novel of Austerlitz is constructed—it is the point zero of the novel.

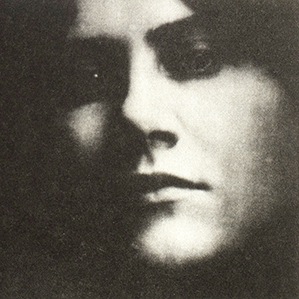

As the search for his parents culminates, Austerlitz discovers a photograph of an anonymous actress in the Prague Theatre Archive, whom his former nanny identifies as his mother. The photograph appears later in the novel, and shows a “ghostly white face, marked by the mother’s penetrating eyes and ominous expression.” The spectral quality of her face is exaggerated by the surrounding darkness, her face receding into the photographic black beyond, exaggerating the ghostly quality of her presence. Rather than bringing closure and structure to Austerlitz’s perceived past, the photograph works to reinforce his inability to order time, his inability to reconstruct his parents’ past, and he is haunted by the spectre of his mother gazing back at him. Furthermore he rejects this photograph “as a memento”, a mere likeness, and not the mother-image he so desperately seeks: “That’s almost the way she was!,” wrote Barthes, noting the absolute pain of approximation in the search for the essential mother-image. Austerlitz’s ethical responsibility to the past does not end with the discovery of this photograph, he is bound to continue, in search of his father, and thus placing our protagonist into an indefinite bind with a past he is unable to adequately define in time. Austerlitz seems to have a central motif of the tracing of paths. Paths across the countryside, and paths backwards, two principles that seem to be pushing against each other.

Inevitably, Sebald is a mythologist; he leads us through villages and roads, planting non sequitur’s along away, his prose hiding in the shadows and fog-filled English landscapes, that are inevitably containers of as much fiction as reality. Sebald, like his protagonist Austerlitz, is bound to the past, to the fate of his parents, and he is both implicated and entombed by his writing. He has self-mythologised to the extent that personal history has become bound and transfigured through the lens of collective, shared experience, and in the wake of his death, we look for him in the pages of his books, and the road that he walked.

Unlike Barthes, Austerlitz’s search for the essential mother-image is unfulfilled. Late in the novel, he re-examines, with the aid of a magnifying glass, the photograph of himself standing in an empty field at dawn, his piercing gaze looking out through the photograph’s surface, and back at the older Austerlitz. Rather than discovering the mother-image as he so desperately desires, and as Barthes successfully finds, what Austerlitz discovers, is the image of himself, at five years old—the eternal age of Barthes’s mother—in the very last moments of seeing her.

That Sebald never mentions the dark star around which his characters constantly orbit—sleeplessly in Austerlitz’s case—is significant. He knew too well that to speak directly of the horrors of the holocaust would militate against its proper discussion, would scorch the memory of the very thing he was attempting to countenance, to comprehend. Instead he refers to it tangentially, obliquely. It is better regarded as one does the sun during an eclipse, he seems to be saying, by projecting the light onto a board through a pinhole.

There is a single photograph of the character of Austerlitz as a young pageboy, which adorns the cover of the book itself—it is the only photograph of Austerlitz, and he is presented to us as a child, costumed from another time. This presentation of the Austerlitz as his former, forgotten self, prescribes how his identity must be defined in the context of his relationship to his parents—both for us as reader and participant, and for Austerlitz himself. In the photograph he stands defiantly, in a fog-filled landscape, staring steelily at the camera: It is an adult’s gaze, an adult’s posture, as if the older, wiser Austerlitz were embodied in the eyes of his former, childhood self. There are only a handful of photographs depicting human subjects on the pages of Austerlitz, and of these photographs, even fewer maintain what Roland Barthes referred to as “the frontal pose [...] of looking me straight in the eye.” For Barthes, the gaze of the subject (the Spectrum) toward the eye of the camera is the ultimate affirmation of the photograph’s noeme (what differentiates the photograph from other, non-photographic images), from the point of view of the Spectator (the viewer). This single photograph of a boy looking straight down the lens of the camera and directly at us, the viewer, as we learn from an interview with Sebald, is the foundations where upon the entire novel of Austerlitz is constructed—it is the point zero of the novel.

As the search for his parents culminates, Austerlitz discovers a photograph of an anonymous actress in the Prague Theatre Archive, whom his former nanny identifies as his mother. The photograph appears later in the novel, and shows a “ghostly white face, marked by the mother’s penetrating eyes and ominous expression.” The spectral quality of her face is exaggerated by the surrounding darkness, her face receding into the photographic black beyond, exaggerating the ghostly quality of her presence. Rather than bringing closure and structure to Austerlitz’s perceived past, the photograph works to reinforce his inability to order time, his inability to reconstruct his parents’ past, and he is haunted by the spectre of his mother gazing back at him. Furthermore he rejects this photograph “as a memento”, a mere likeness, and not the mother-image he so desperately seeks: “That’s almost the way she was!,” wrote Barthes, noting the absolute pain of approximation in the search for the essential mother-image. Austerlitz’s ethical responsibility to the past does not end with the discovery of this photograph, he is bound to continue, in search of his father, and thus placing our protagonist into an indefinite bind with a past he is unable to adequately define in time. Austerlitz seems to have a central motif of the tracing of paths. Paths across the countryside, and paths backwards, two principles that seem to be pushing against each other.

Inevitably, Sebald is a mythologist; he leads us through villages and roads, planting non sequitur’s along away, his prose hiding in the shadows and fog-filled English landscapes, that are inevitably containers of as much fiction as reality. Sebald, like his protagonist Austerlitz, is bound to the past, to the fate of his parents, and he is both implicated and entombed by his writing. He has self-mythologised to the extent that personal history has become bound and transfigured through the lens of collective, shared experience, and in the wake of his death, we look for him in the pages of his books, and the road that he walked.

Unlike Barthes, Austerlitz’s search for the essential mother-image is unfulfilled. Late in the novel, he re-examines, with the aid of a magnifying glass, the photograph of himself standing in an empty field at dawn, his piercing gaze looking out through the photograph’s surface, and back at the older Austerlitz. Rather than discovering the mother-image as he so desperately desires, and as Barthes successfully finds, what Austerlitz discovers, is the image of himself, at five years old—the eternal age of Barthes’s mother—in the very last moments of seeing her.

That Sebald never mentions the dark star around which his characters constantly orbit—sleeplessly in Austerlitz’s case—is significant. He knew too well that to speak directly of the horrors of the holocaust would militate against its proper discussion, would scorch the memory of the very thing he was attempting to countenance, to comprehend. Instead he refers to it tangentially, obliquely. It is better regarded as one does the sun during an eclipse, he seems to be saying, by projecting the light onto a board through a pinhole.

The Dream Life of Debris pt. 1

Jun 02, 2015 - Peter Watkins

(The following is taken from my MA dissertation which was also titled The Unforgetting. This is a passage on W.G. Sebald's novel Austerlitz which I have broken up into two separate posts. Apologies in advance for the stripped footnotes.) W.G. Sebald’s post-war novel Austerlitz portrays the central character of Jacques Austerlitz through the accounts of the narrator, an unlikely friend who has conversed with Austerlitz over a span of several years. The novel relates the plight of Austerlitz through the voice of an equally melancholic narrator, with both parties afflicted by a deep sadness that we are at first unable to find the cause of. Austerlitz, a Czech Jew, is evacuated to London’s Liverpool Street station, arriving on the Kindertransport in WWII, and grows up in Wales having suppressed the trauma of his experience of leaving his native Czechoslovakia, and with no memory even in his adult life of his childhood origins. W.G. Sebald’s prose style resists classification. In a conversation with his publisher he once argued that his books should not merely rest on the shelves of fiction, but should inhabit every genre—they ought be found in every section! As such, his work can be thought of in terms of the historical, anthropological, biographical, and as travelogue. Like a historical novel, its function does not rest with retelling history, or indeed in correcting, but rather to make history appear. Sebald’s prose is shrouded in melancholia, and an ever-present greyness and bleakness hangs over the precise, anthropological wanderings. Sebald’s narrator is forever on the move: walking through obscure locations, drawing us into the often overlooked substrata of the world’s surface, there seems to be a fear of coming to a standstill, but when he does, it is as if the world rips open to some dark truth, and Sebald’s narrator, rather than turn away, tips into this darkness, his gaze unwavering, and reveals to us inherent, uncanny interconnections between the world of objects, the natural world, time, history, architecture, and the formation of the self. Vladimir Nabakov writes in Transparent Things that “when we concentrate on a material object, whatever its situation, the very act of attention may lead to our involuntarily sinking into the history of that object…. Transparent things, through which the past shines!” This is what one commentator in the film Patience: After Sebald refers to as “the dream life of debris”, attributing this phrase to Nabakov. This is the world as Sebald encourages us to engage with it. In Sebald’s writing, the trauma of loss is ever present; yet its site is not explicitly talked about—a refusal to recount the traumatic event— rather it is referred to through a collective memory of loss set in a post- WWII Europe. Through the narrator’s eyes, we travel in a landscape marred by this collective history, and sink into its surface, feeling the grain of a past that reverberates through us with each passing page. Sigmund Freud famously made a distinction between mourning and melancholia. The mourner moves from a position of grief, and arrives at an acceptance of loss. The melancholic, in contrast, displays a pathological and prolonged mourning. As Freud posited, the melancholic incorporates the lost object into the psyche through a process of devouring, which he terms “cannibalistic”. Anne Cheng suggests that through this process of devouring “the melancholic subject fortifies him—or herself and grows rich in impoverishment.” The melancholic is feeding off the lost object, and satiated by the devouring of this loss is forever focused on an “insistent talking about himself ”. This is what for Freud “predominates in the melancholiac.” Sebald seems to be challenging the assertion that the melancholic’s relationship with time is unproductive, and suggests that the melancholic is occupied by an ethical obligation not to forget. Midway through the novel, Austerlitz, suffering from insomnia, is drawn to “nocturnal wandering through London.” It is in these journeys through London’s gloomy streets that he encounters “familiar faces” that haunt him through their spectral, unidentifiable quality. Josephine Carter suggests that by aligning Austerlitz’s melancholia with depictions of the ghostly other, Sebald is suggesting that his protagonist is doing more than attempting to reconstitute his subjectivity through time, he is seeking a subjectivity of time dependent of the Other. During his nocturnal wanderings, he is “irresistibly drawn back” to London’s Liverpool Street Station, the emblematic site of exposure, where he was separated from his parents, and where the architectural grandness of the glass-and-iron roof first left its impression on his boyhood self, and the source of his greatest revelation—he would later become an architect of notable stature. It is here, in an abandoned waiting room, that he is shocked back into the memory of being in this place as a child with his parents. Austerlitz is drawn to reconstructing his parents’ past, of reconstituting his identity through the loss of the Other, and the proposal of an Other time, whereby the present generation are placed in the position of witness of the past. Time, for Austerlitz, is characterised by a series of “appointments”: Appointments in the present, appointments in the past, and appointments in the future; as if the future had already taken place. As he explains: “It seems to me then as if all the moments of our life occupy the same space, as if future events already existed and were only waiting for us to find our way to them at last, just as when we have accepted an invitation we duly arrive in a certain house at a given time. And might it not be [. . .] that we also have appointments to keep in the past [. . .] and must go there in search of places and people who have some connection with us on the far side of time.” This proposition of an Other time places the emphasis away from the Ego’s vision of the world, toward its relationship with the Other, and through this, we come to understand the importance laid upon his relationship with his parents, and his relationship to the past.

The Fall of Rome

Jun 01, 2015 - Peter Watkins

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c9OWlCENC3w[/embed]

The Search for Ecstatic Truth

May 29, 2015 - Peter Watkins

href="https://dergreif-online.de/www/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/img026-retouch.jpg"> It was around the time of the 20th anniversary of my mother’s death that I decided to embark on making a film that would explore her drowning. My father had recently passed away and we had put off talking about everything that had happened during that period—an epitome of that very British sensibility of inexpression in the face of that which can not be named; the inexplicability of voicing emotions. Although far from being a trauma of repression, her death had been very present all my life, but it was something that I had largely internalised, that is to say it lay just beneath the surface, lining and becoming a part of all newly found experiences to come. The death of a loved one to a child has the curious effect of fucking you up, and making you harder, more perceptive, and irrevocably different, all at the same time. It unlocks in you a totally different sense of the world—and I mean that in real terms, not in some loftily, rhetorical sort of way—and shows you that death is not some abstract far off unfathomable thing, but rather that it is something tangible and real, something very present, something that can happen. You realise you are living and breathing and it encourages you, too young perhaps, to start figuring out what it is you’re doing in the world. At such a tender age you don’t necessarily understand all of this in these terms; it all tends to show itself in way more destructive, unreasonable, and unproductive ways. Nevertheless this experience shapes you—like those big, game-changing experiences do—and determines, in a very decisive manner, everything that presents itself thereafter.

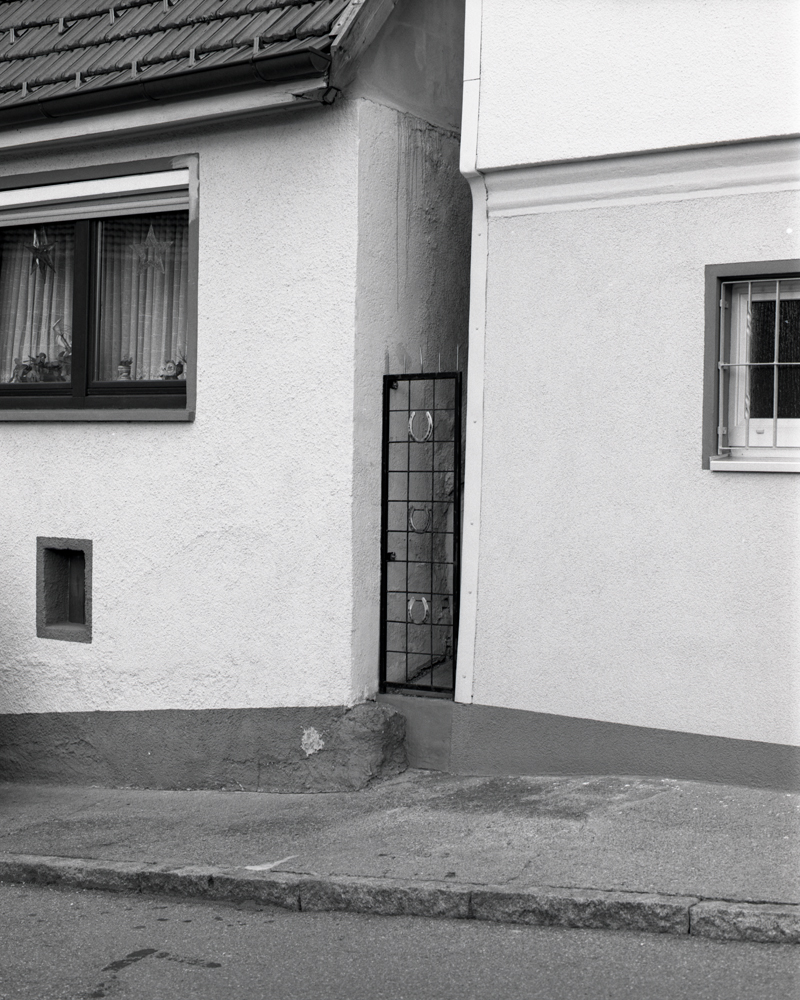

After my mothers death we spent our summers in rural Germany, at my Oma’s house in the village where my mother had grown up. My relationship with this place is that of the intimate outsider. I know every corner of it, I can still smell the deep red tomatoes growing, and the way the soil felt in my hand when I would unearth them over the floor. I’ve explored this place for countless hours on bicycles as a child, and later with a camera and a video camera.

By all intention I was going to make a film that explored the shared sense of memory that we as a family shared. I wanted to find out exactly what had happened before the people who had lived through it were no longer able, or were no longer there to tell the story. I was really into Werner Herzog’s documentary-style of filmmaking at the time (still am), where he overlaps interviews, with history, storytelling, and his own peculiar narrative driven style. I wanted to make a talking heads kind of film, quite straight, but tap into that kind of “ecstatic truth” that I believe Herzog coined. I think I made thirty plus hours of footage over the course of the year, interviewed all relevant parties, asked uncomfortable questions, and got some answers. I even took a road trip with my good friend Oli to Zandvoort, in the Netherlands where in February 1993 they had found her body. We travelled there on the 20th anniversary, and I went down on the beach at dawn, approximating where I thought she might have entered the water, expecting to feel something, my video camera pointing out to sea. But when you go out looking for such moments, when you force things too much, you don’t tend to feel that thing you’re seeking… When this didn't feel like enough I even went so far as to visit the local police station to dig up some records, but her case predated computer entries, and the paper files would be near-impossible to go back through now, as no one had organised them they hadn’t been digitised—“its so far back now,” the police officer told me, “there really wouldn’t be much sense in it.”

I made several edits of the film and made more footage—chopping wood with my Opa, the church clock chiming, lights through windows, a man cross country skiing alone at nightfall—but all this remained unfinished. I’ve come to think of it now as preparatory research for my photographic works which I’ve called The Unforgetting. Until recently I thought I would keep all this footage to myself as something that might be interesting later on, more of a private reflection than something to be shown to a public, but somehow its slipped back into my mind of late, and I have started exploring a new way of bringing all this together.

It was around the time of the 20th anniversary of my mother’s death that I decided to embark on making a film that would explore her drowning. My father had recently passed away and we had put off talking about everything that had happened during that period—an epitome of that very British sensibility of inexpression in the face of that which can not be named; the inexplicability of voicing emotions. Although far from being a trauma of repression, her death had been very present all my life, but it was something that I had largely internalised, that is to say it lay just beneath the surface, lining and becoming a part of all newly found experiences to come. The death of a loved one to a child has the curious effect of fucking you up, and making you harder, more perceptive, and irrevocably different, all at the same time. It unlocks in you a totally different sense of the world—and I mean that in real terms, not in some loftily, rhetorical sort of way—and shows you that death is not some abstract far off unfathomable thing, but rather that it is something tangible and real, something very present, something that can happen. You realise you are living and breathing and it encourages you, too young perhaps, to start figuring out what it is you’re doing in the world. At such a tender age you don’t necessarily understand all of this in these terms; it all tends to show itself in way more destructive, unreasonable, and unproductive ways. Nevertheless this experience shapes you—like those big, game-changing experiences do—and determines, in a very decisive manner, everything that presents itself thereafter.

After my mothers death we spent our summers in rural Germany, at my Oma’s house in the village where my mother had grown up. My relationship with this place is that of the intimate outsider. I know every corner of it, I can still smell the deep red tomatoes growing, and the way the soil felt in my hand when I would unearth them over the floor. I’ve explored this place for countless hours on bicycles as a child, and later with a camera and a video camera.

By all intention I was going to make a film that explored the shared sense of memory that we as a family shared. I wanted to find out exactly what had happened before the people who had lived through it were no longer able, or were no longer there to tell the story. I was really into Werner Herzog’s documentary-style of filmmaking at the time (still am), where he overlaps interviews, with history, storytelling, and his own peculiar narrative driven style. I wanted to make a talking heads kind of film, quite straight, but tap into that kind of “ecstatic truth” that I believe Herzog coined. I think I made thirty plus hours of footage over the course of the year, interviewed all relevant parties, asked uncomfortable questions, and got some answers. I even took a road trip with my good friend Oli to Zandvoort, in the Netherlands where in February 1993 they had found her body. We travelled there on the 20th anniversary, and I went down on the beach at dawn, approximating where I thought she might have entered the water, expecting to feel something, my video camera pointing out to sea. But when you go out looking for such moments, when you force things too much, you don’t tend to feel that thing you’re seeking… When this didn't feel like enough I even went so far as to visit the local police station to dig up some records, but her case predated computer entries, and the paper files would be near-impossible to go back through now, as no one had organised them they hadn’t been digitised—“its so far back now,” the police officer told me, “there really wouldn’t be much sense in it.”

I made several edits of the film and made more footage—chopping wood with my Opa, the church clock chiming, lights through windows, a man cross country skiing alone at nightfall—but all this remained unfinished. I’ve come to think of it now as preparatory research for my photographic works which I’ve called The Unforgetting. Until recently I thought I would keep all this footage to myself as something that might be interesting later on, more of a private reflection than something to be shown to a public, but somehow its slipped back into my mind of late, and I have started exploring a new way of bringing all this together.