Sarah Mei Herman

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

Stacy Mehrfar - The Moon Belongs to Everyone

Mar 15, 2017

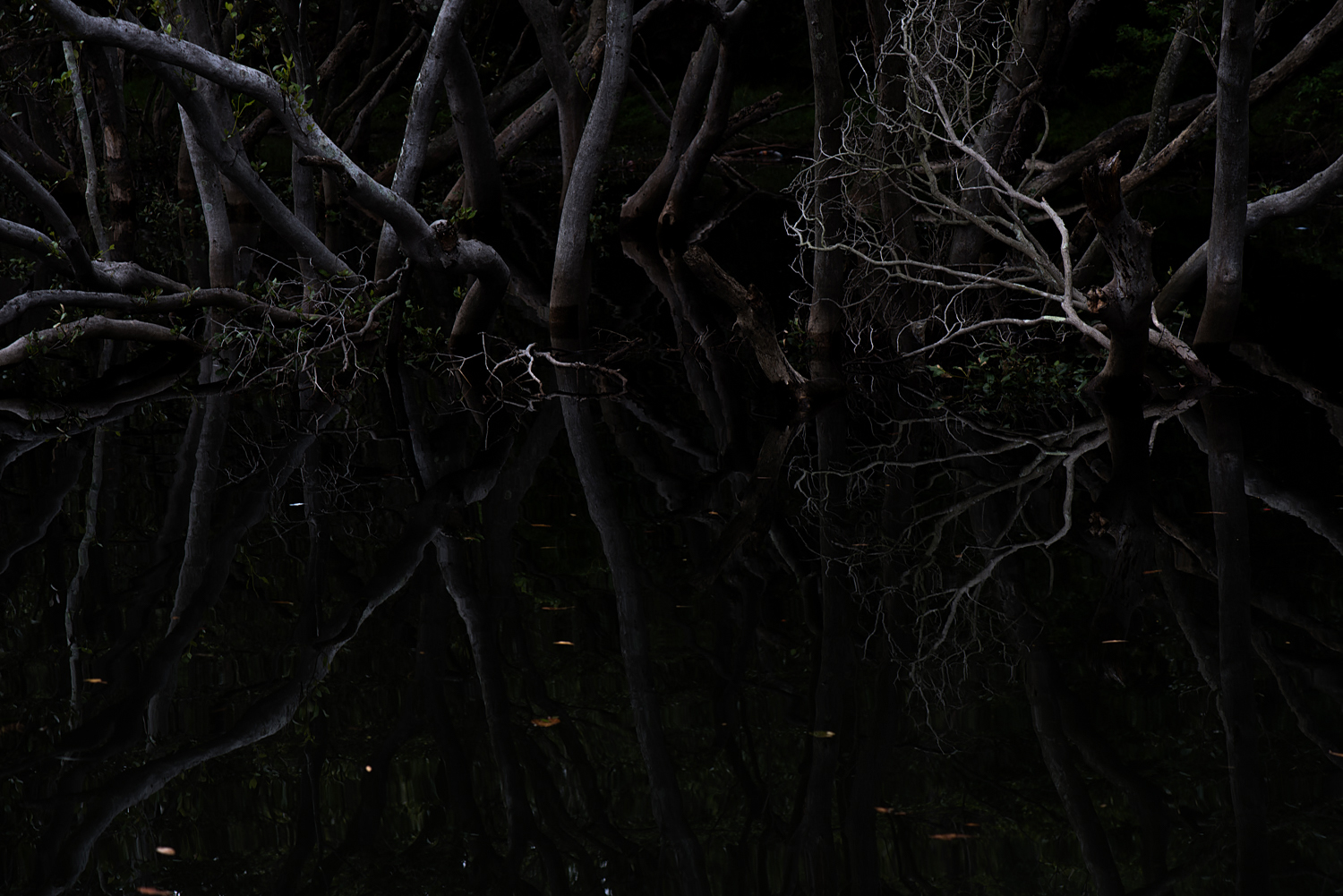

The Moon Belongs to Everyone, depicts the contemporary experience of migration, of shifting continents and mindsets. A multi-layered narrative set in a non-locatable landscape, The Moon Belongs to Everyone, frames a metaphor for an increasingly ubiquitous, non-specific, ever-changing, global identity.

The subjects hail from different parts of the world; they don’t know one another, nor do they share the same heritage. And yet, they each find themselves caught in a similar liminal space — hovering somewhere between ‘there’ and ‘here.’ The Moon Belongs to Everyone, is an allegory for a new global identity positioned in the in-between; an identity suspended between origin and destination, located in the crosshairs between the dissonant and the lyrical; a space I personally found myself in after leaving my homeland and migrating to a new country.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Der Greif #9«

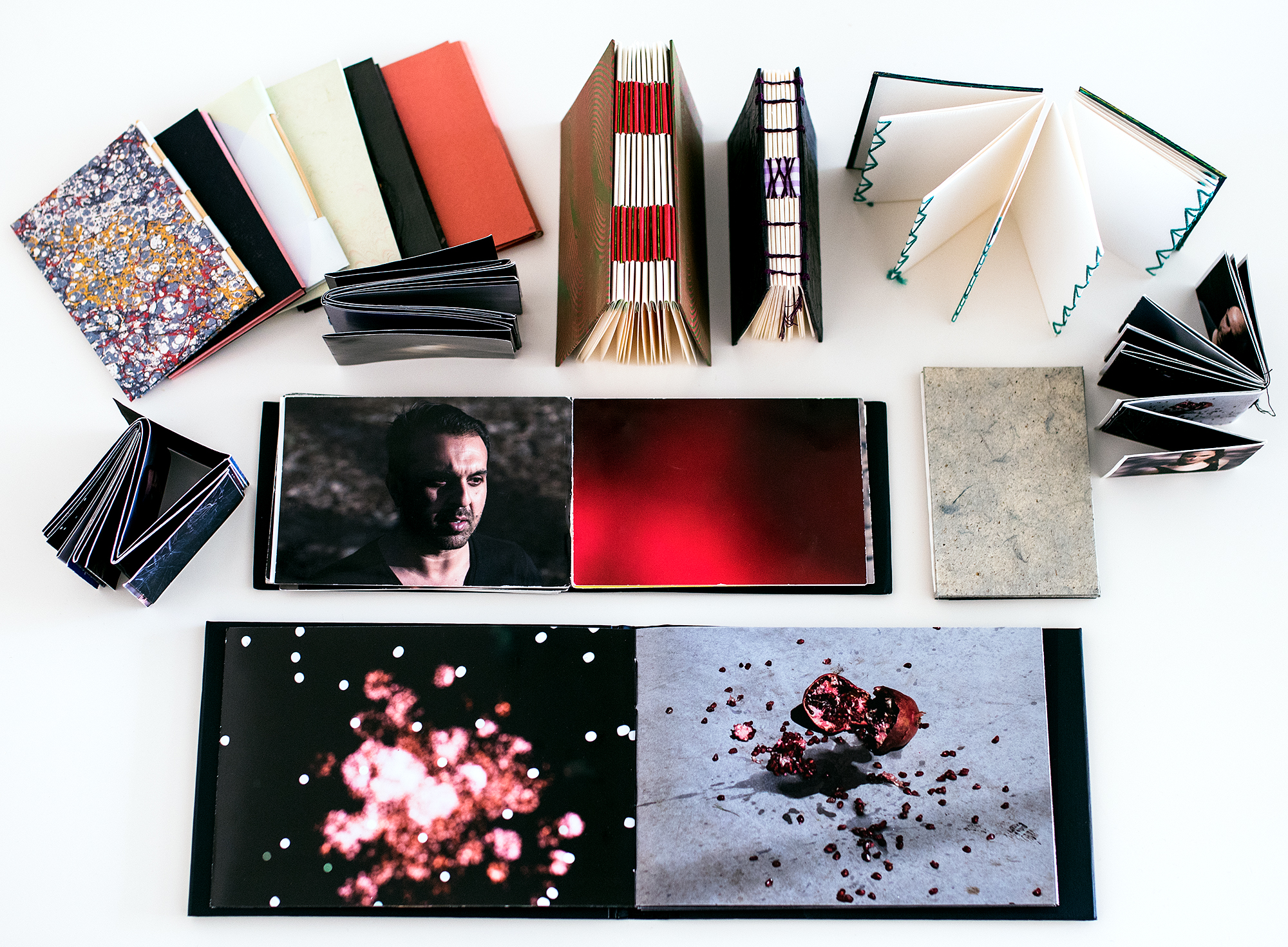

The Moon Belongs to Everyone Maquettes

Mar 23, 2017 - Stacy Mehrfar

To resolve the design of the artist book, The Moon Belongs to Everyone, I attended several bookmaking workshops. Making various types of books by hand meant that I could physically grasp the strengths, weaknesses, structure, practicality, and function of the book-object. I took what I learned from making lots of different styles of books to make miniature maquettes for The Moon Belongs to Everyone. The maquettes allowed me to determine what sorts of papers worked best, how to design the pages, the folds, and how to order the images. Once I had finalized the maquette, I looked for a local printer who could produce the artist book. In the end I went with Momento Pro in Sydney, Australia — they worked one on one with me to make sure the finished object matched what I expected. I only made 10 copies. In hindsight, I should’ve made more. I am currently editing the trade edition of The Moon Belongs to Everyone – teaming up with a publisher I am very excited to work with.

Thank you to Der Greif for including me in the Artist Feature and Blog. And thank you to y’all who have stuck around to read my thoughts. Please follow along with me on instagram as I figure that out next.

Protest Portraits, Instagram, and Women’s History Month

Mar 22, 2017 - Stacy Mehrfar

I recently moved back to the United States after living abroad for the past 8.5 years. Following the inauguration of the current American President — and as news came out about his policies — I became angry and despondent. I began attending rallies in an effort to appease my frustrations. Soon I began photographing at them. Making portraits at rallies has helped me to find my personal thread within the current American social fabric.

A selection of these Protest Portraits are on my instagram page. Have a look. Scroll down to see additional images from The Moon Belongs to Everyone. And feel free to like and follow — I’m keen to engage with you.

In the spirit of Women’s History Month, here’s a list of women making a mark on instagram (in no particular order):

Ruth Van Beek: @ruth_van_beek

Maroesjka Lavigne: @maroesjkalavigne

Birthe Piontek: @birthepiontek

Simone Rosenbauer: @simonerosenbauer

Maria Louceiro: @marialouceiro

Haley Golden: @haleygolden_

Heidi Romano: @heidiromano

Sara Palmieri: @sarapalmieri1

Sarah Rhodes: @myvisualstoryteller

Dragana Jurisic: @dragana23

Sarah Wilmer: @sarahwilmersarahwilmer

Melanie Flood: @melanie.flood

Ying Ang: @yingang

Sarah Walker: @sarahjwalker

Kate Cunningham: @kacunningham

Allison Beonde: @allisonbeonde

Naomi Harris: @mapledipped

Katrin Koenning: @k_koenning

Hoda Afshar: @hodaafshar

Rachel Papo: @rachelpapo

I Called Out for the Mountains, I Heard them Drumming, Miia Autio

Mar 21, 2017 - Stacy Mehrfar

I recently came across the work of Miia Autio, a Finnish photographer, entitled I Called Out for the Mountains, I Heard them Drumming. In this work, Autio explores landscape as a referent to home, and identity.

Artist Statement:

The connection between nature and one’s identity as well as the idea of landscape as a component of national belonging is a subject that everyone has a personal relationship with. The series approaches these themes in the context of political displacement.

The series tells about Rwandan refugees who have escaped to Europe and about the memories of their original homeland. It portrays Rwandans in several European countries and the landscapes of their memories in Rwanda. The portraits, landscapes, and interviews form a cohesive entity that considers the relationship between homeland, landscape, and identity while recognising the subjectivity of memories.

At the same time the complicated history of Rwanda and the recent human rights situation is reflected in the personal histories of these people. They lost their original homeland but finally they found new home countries in Europe. Their experiences have made them world citizens. In the end the main question of the series is, whether home is just a mental image for us all?

The Imaged Landscapes of Todd Hido

Mar 20, 2017 - Stacy Mehrfar

“People sometimes describe my works as voyeuristic. Where I’m standing with the camera feels voyeuristic. I’m backed up far enough away so that we (I and the viewer) are decidedly at a distance from the house. We’re back across the street, on the sidewalk — a safe looking distance. Maybe we’re not too close because we’re not supposed to be there. I’ve always used this odd distance that communicates, ‘I’m not from there’. Viewers feel that distance and actually become more aware of my presence as a photographer/voyeur. I place them in the same position — a position that encourages a certain type of looking.” —Todd Hido, On Landscapes, Interiors, and the Nude

I was lucky. Many years ago I had the opportunity to assist Todd Hido when he taught a class on night photography at the International Center of Photography, in New York. Hearing him speak about his practice was eye opening. His first book, House Hunting (Nazraeli Press, 2001), portraits of suburban homes and apartments mostly photographed at night, can be seen as antithetical to the image of the American dream.

Hido’s photographs invite the viewer to contemplate solitary imaged landscapes. The photographs in Houses at Night often leave the spectator feeling overwhelmed by a sense of unease, of tension, as if something has just occurred or is lurking in the shadows. Most often shot at night, and always absent of the physical presence of people, Hido mostly avoids a straightforward look onto the ‘photographic event’ — the camera placement usually associated with documentary photography — rather he predominately places his camera at an angle and from a distance. This perspective creates a particular viewpoint onto the imaged landscape. As Anthony LaSala writes: “Either smothered in fog and haze, bathed in awkward orange light or radiating an uneasy feeling about the people hiding within, the images don’t simply entice gazes, but also raise questions.”(1) Hido’s camera perspective positions the viewer’s gaze as voyeur, effectively encouraging “a certain type of looking.”

The colour, light, and this compositional perspective meld together to produce a gaze emanating from the image, suggesting to the viewer a feeling of being on the outskirts. The viewer is then left to contemplate the consequence of what may have occurred (or may soon occur) in the imaged space. Hido speaks eloquently about his photographs: “that’s the thing that resonates with me in the landscape pictures; they reflect how the mind works. They’re a metaphor for memory.”

1. Anthony LaSala, “Todd Hido’s Haunted Houses,” Photo District News 21, Issue 10 (Oct 2001), 44.

The Age Old Question

Mar 19, 2017 - Stacy Mehrfar

What makes a good portrait? That’s a question I throw around on a daily basis. It’s safe to say that the answer changes just as often.

While researching for The Moon Belongs to Everyone, I played close attention to the way different artists have tackled the photographic portrait. Here I will go into detail about three artists who’s work I admire and who’s photographs have long influenced my thinking, and my practice.

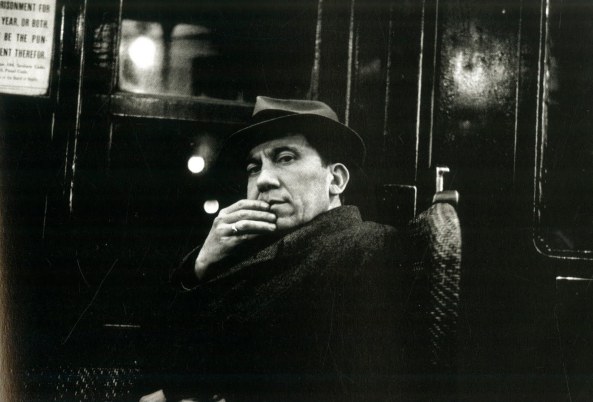

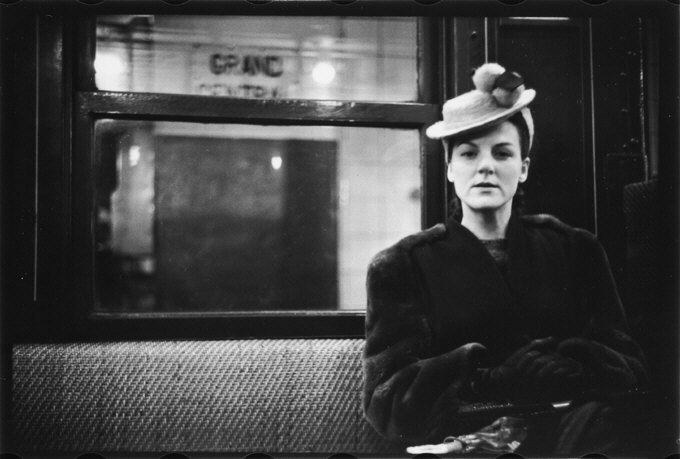

Walker Evans, Many Are Called: Between 1936 and 1941, Walker Evans, one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, photographed passengers in New York City subway cars in what came to be the book entitled, Many Are Called. These photographs were essentially shot ‘from the hip’; Evans hid a camera beneath his coat and a shutter release down his coat sleeve so he could be as surreptitious as possible. The images captured the ordinarily unseen – essentially presenting photography’s ability to depict the in-between, the unguarded, expressions of a human subject. Of the images in Many Are Called, Evans writes, “[These images are] my idea of what a portrait ought to be: anonymous and documentary and a straightforward picture of mankind.” (1)

We are given very little information about the subjects of the photographs. However, Evans’ camera seemingly crosses the boundary from the curious to the familiar, where the photographed subjects ostensibly transform into representations, or allegories, for human emotion. The individual photographs can be seen as an observation of a contemplative moment of a given subject. However, viewed together, the series of images forges a story, a metaphor, a picturing of a group of people in a specific place at a specific time. With each turn of the page, we become aware that what we are observing is a collective identity of New York City in a specific moment in time.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Heads: American photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia also intended to make an artwork that offered an intimate look at New York City’s collective identity. This work, entitled Heads, was exhibited in September 2001 (it opened one week before the tragic events of 9/11 in New York City), and was concurrently published in a book. The significance of diCorcia’s Heads is the exploration of what the camera reveals through ‘the gaze’ and how that gaze can evoke meaning through portraiture. With the camera positioned at a distance of 20 feet, and a flash and a trigger set up on the scaffolding of the streets of New York’s Times Square, the subjects of Heads were photographed unawares. The images in the series are all photographic portraits — close-up, intimate, captured moments of anonymous subjects. The use of a telephoto lens and flash bring the subject(s) out from the background, effectively framing images that offer no specificity of location, thereby focusing the viewer’s gaze onto the subjects’ gaze and pose.

diCorcia’s portraits are reminiscent of techniques used by seventeenth-century artists, where the communication of a private, inward state of a subject is suggested through the manipulation of gesture and form, light and shade. With the employment of strongly lit, bold archetypical faces measured against dark, indistinct backgrounds, diCorcia draws on these conventions. The engagement of such effects, or photographic tropes, directs the viewer’s gaze, leaving she or he with the sensation of being caught looking deep within the subject’s inner thoughts.

Rineke Dijkstra, Beach Portraits: Beach Portraits (1992–2002), a series of full-length color photographs of teenagers and children photographed at the ocean’s edge in the United States, Poland, Britain, Ukraine, Gabon, and Croatia, is just one example of Rineke Dijkstra’s photographic portrait work. In this series, as in the majority of her photographs, Dijkstra draws on a standardised, formal aesthetic to directly address individual identity. Without instructing her subjects on how to stand, or sit, or where to look, Dijkstra’s placement of the camera directly in front of her subject(s) is deliberate. Through a direct lens perspective, Dijkstra allows her sitters the power of the gaze: each subject is given the opportunity to gaze back at the viewer and acknowledge that their image is there to be examined. Her photographic portraits are honest, bold, and dynamic. Rineke Dijkstra’s photographs summon the viewer’s attention — forcing us to look, to examine, to decipher, an individual’s identity.

1. Jeff L. Rosenheim, afterword to Walker Evans, Many Are Called, with an introduction by James Agee, foreword by Luc Sante, and afterword by Jeff L. Rosenheim (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in Association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), 198.

Photobook/Artist Books

Mar 17, 2017 - Stacy Mehrfar

The tactility, the feeling of holding the whole world in your hand, learning and knowledge; I love books. The Photobooks/Artist Books I am currently engaged with/ looking at/thinking about are:

Fractal Scars, Salt Water and Tears, Esther Teichmann

Moises, Mariela Sancari

Wild Pigeon, Carolyn Drake

Sequester, Awoiska van der Molen

Imperial Courts, Dana Lixenberg

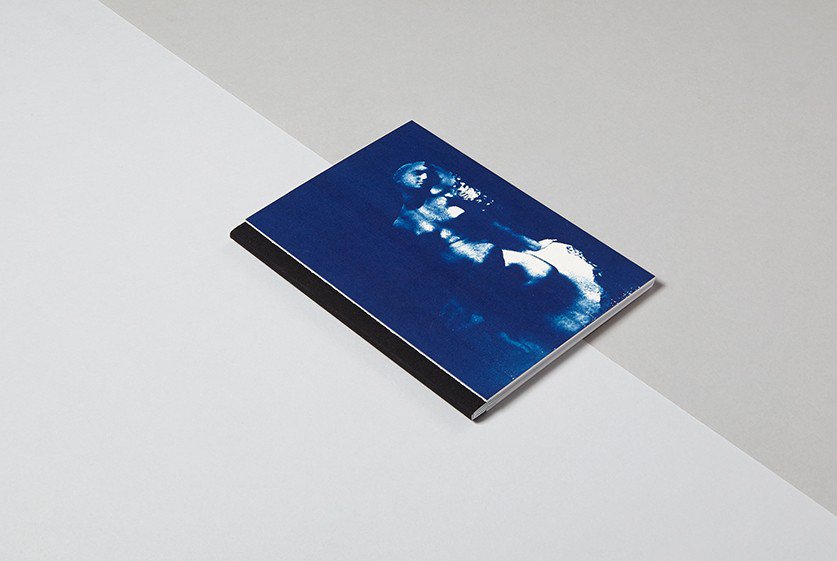

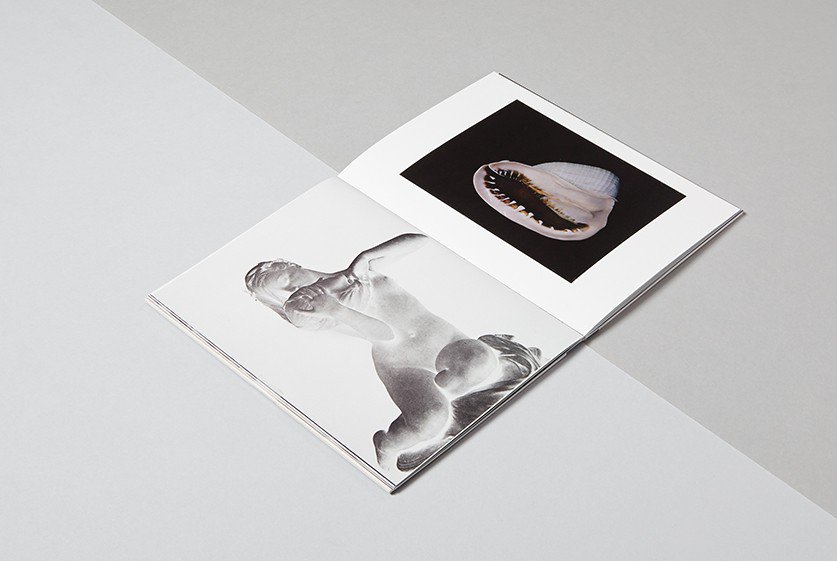

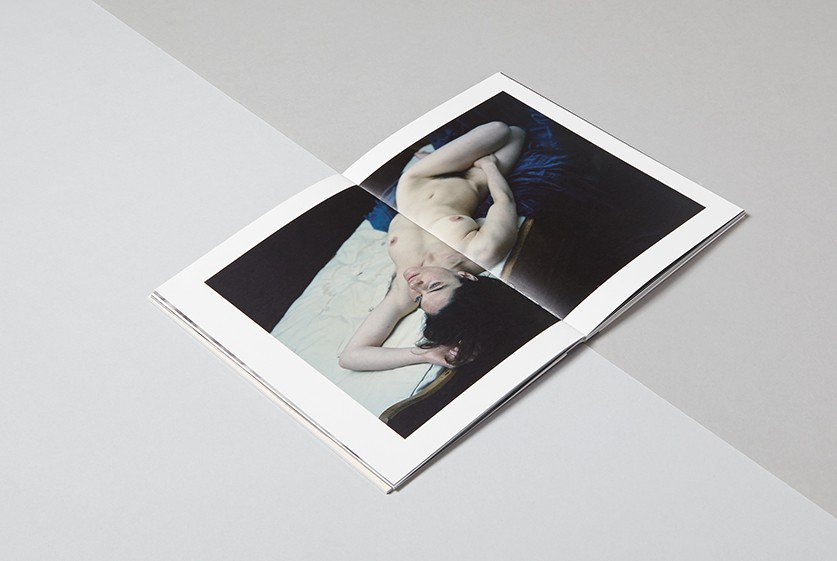

Esther Teichmann’s, Fractal Scars, Salt Water and Tears, published by Selfpublishbehappy SPBH Book Club Volume V, is a book I sit with often. Esther Teichmann (b. 1980) is a German–American artist based in London. Printed in 2014, the artist book is designed by Antonio de Luca and comes with an original cyanotype cover.

At first glance, one is immediately impressed by the printing, the paper, and the editing of this rather small book. But even after we reflect upon the seductive tactility and well considered design elements of the book itself, we are left with a haunting impression. We know we have entered a fantasy world, albeit one that is rooted in history. Teichmann’s images are not only luscious, sensual, beautiful, but they also raise questions and evoke emotions that seem to repeatedly materialize from image to image. There is a constant push and pull, one that lingers and then re-emerges. What is fascinating for me is that she repeats images in different projects as if she still hasn’t answered the question, or perhaps because yet another concern has come to light. This is something I grapple with my own practice, but somehow Esther does it seamlessly, as if it just couldn’t be another way; the past persistently summoned into the present.

Esther has a show up currently at Transformer Station in Cleveland, Ohio, entitled Heavy The Sea. More info here.

She created a zine for the exhibition which you can download here. (Careful, large pdf! Tip: Right-click + Save as)

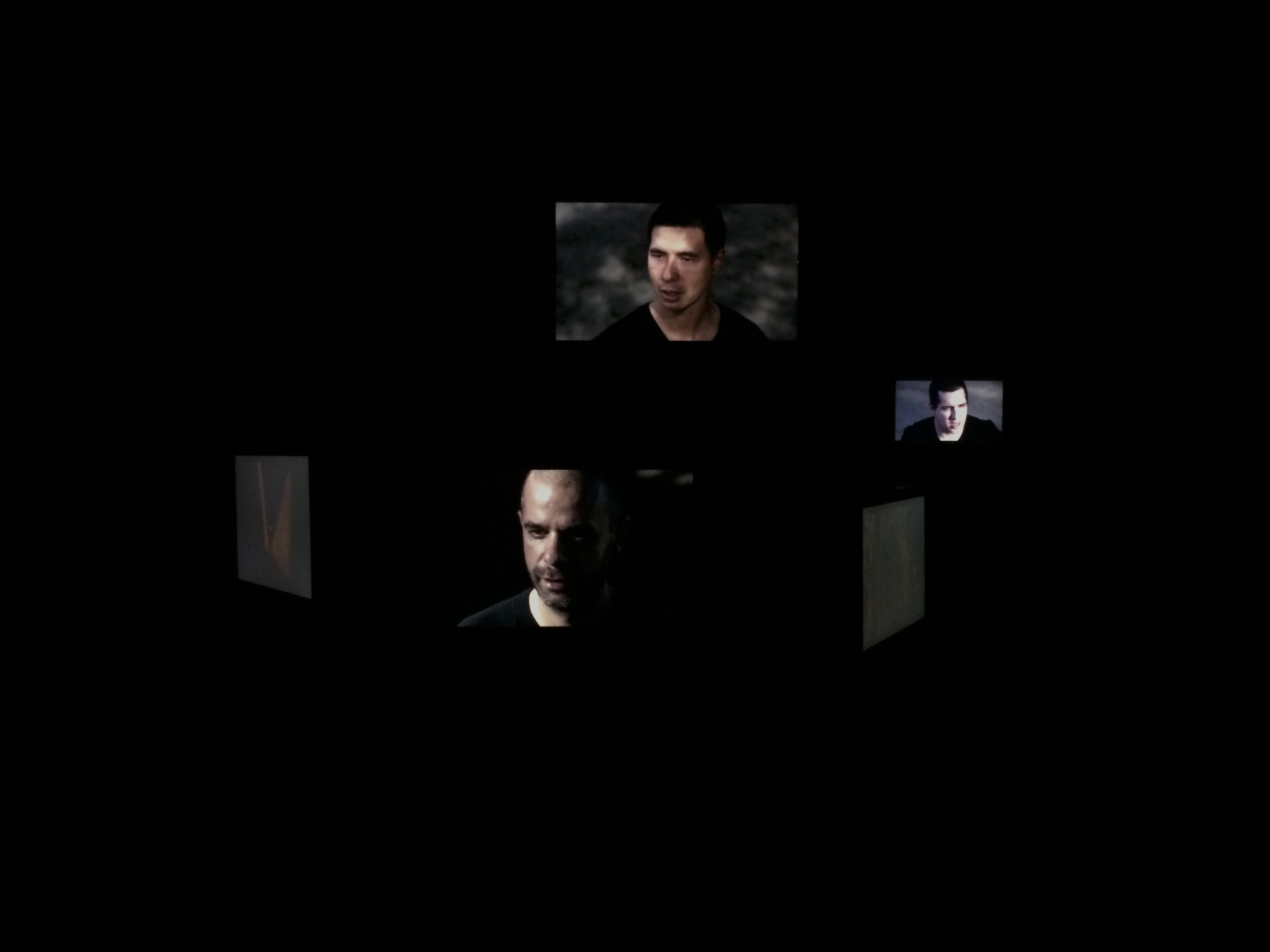

1/4 The Moon Belongs to Everyone, 8 Channel HD Video, Suspended Screens, Loop, 16:9, Colour, Stereo Sound | Black Box Gallery, October 2015

2/4 The Moon Belongs to Everyone, 8 Channel HD Video, Suspended Screens, Loop, 16:9, Colour, Stereo Sound | Black Box Gallery, October 2015

In the In-Between

Mar 16, 2017 - Stacy Mehrfar

“..Our identity is at once plural and partial. Sometimes we feel that we straddle two cultures; at other times, that we fall between two stools.” – Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981-1991

In my home, cultures from all four corners of the world are distilled into one. I myself am American, Iranian, Jewish, and now, since having lived in Sydney for 8.5 years, semi-Australian. My partner was born in South Africa, and while his ancestors hail from Belgium and Russia, he identifies as Australian. We have two kids. On a daily basis I witness a blending of all these influences on our home. Our children will grow up identifying with a hybrid, global identity, one that is not routed in a definitive landscape, but rather somewhere within the juxtaposition of many.

Truth is, in today’s globalized world, we can no longer define one’s culture by national borders. The Moon Belongs to Everyone, is a response to this sense of being un-identifiable – not belonging here, nor there – but rather existing in the in-between.

The Moon Belongs to Everyone, is both an immersive multi-channel video installation and an artist book. The video installation consists of eight non-linear, moving ‘narratives’ made up of a montage of photographic stills and fragments of still-video, displayed on suspended screens in a blackened gallery space. The installation forms an ever-shifting architectural environment, encouraging the viewer to navigate around the screens to negotiate the narrative themselves. There is no specific viewing position with which to experience the artwork; I wanted the installation to emotionally and viscerally affect the viewer — to engage their sensation of spatial dislocation.

In continuing with the themes of an ever-shifting environment, the artist book is comprised of 36 plates, printed on transposable pages. The viewer is given authority to (re)position the pages and personally construct multiple narratives. New narratives may unfold with each interaction with the book. Presenting a kaleidoscope of seemingly diverse individuals viewed in isolation against a common, indeterminate landscape, The Moon Belongs to Everyone, in both its iterations, suggests that identities, histories, and memories, are perhaps continuously in flux.