Daniel Everett

Artist Feature

Every week an artist is featured whose single image was published by Der Greif. The Feature shows the image in the original context of the series.

Tereza Zelenkova - A land with the secret heartbeat

Jun 29, 2016

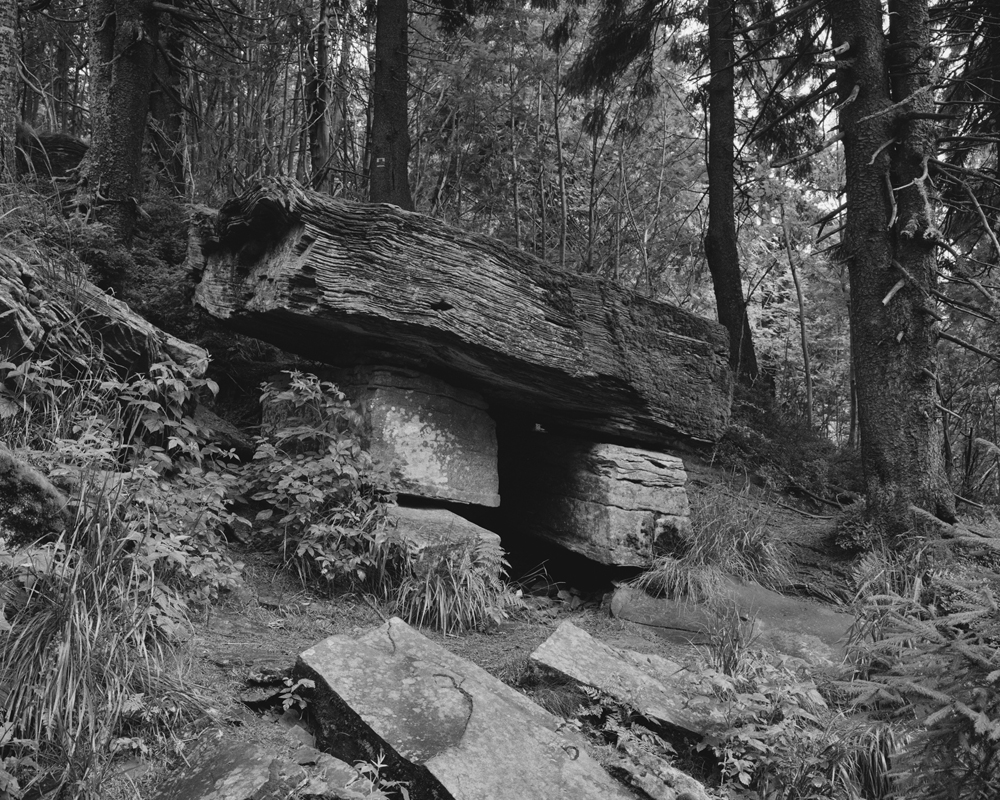

My latest ongoing project is an attempt to create a portrayal of my home country, reflecting its peculiar beauty, which I believe is imbued with elements of darkness and melancholy, occasionally seeping to the surface through morbid fairytales, forgotten biographies, local histories and also superstitions. The locations that I’m particularly interested in are those with histories bordering with mysticism or in some way fulfilling my own personal image of what constitutes the mystery permeated landscape of my childhood. The places that I photograph range from castles, primeval forests, and ritual monuments, to folk architecture and reliefs carved into sandstone rocks, which are typical natural landmarks in many parts of the Bohemian landscape. Generally said I’ve been interested in a kind of transcendental landscape, as a space that’s infused with its own mythologies and that further opens up to the imagination. Although part of the work has been exhibited already, the work on this is still very much in progress and the ultimate outcome will be a book of photographs and texts.

Artist Blog

The blog of Der Greif is written entirely by the artists who have been invited to doing an Artist-Feature. Every week, we have a different author.

Published in:

»Guest-Room Jörg Colberg«

»Der Greif #9«

The Sandstone Landscape of Central Bohemia

Jul 06, 2016 - Tereza Zelenkova

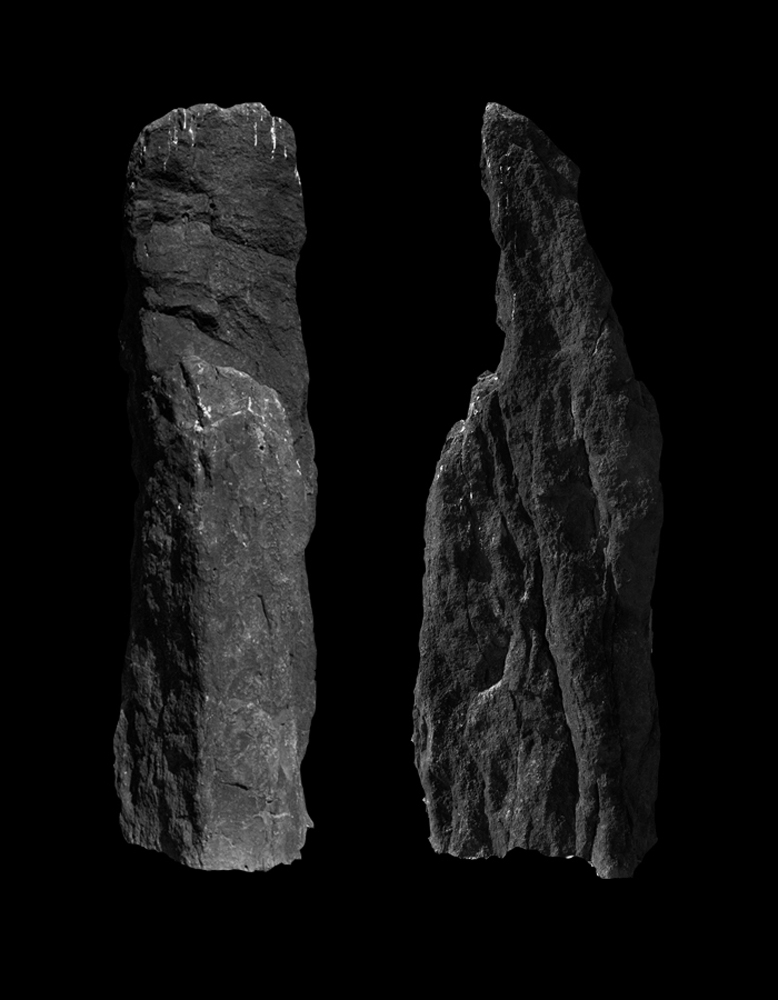

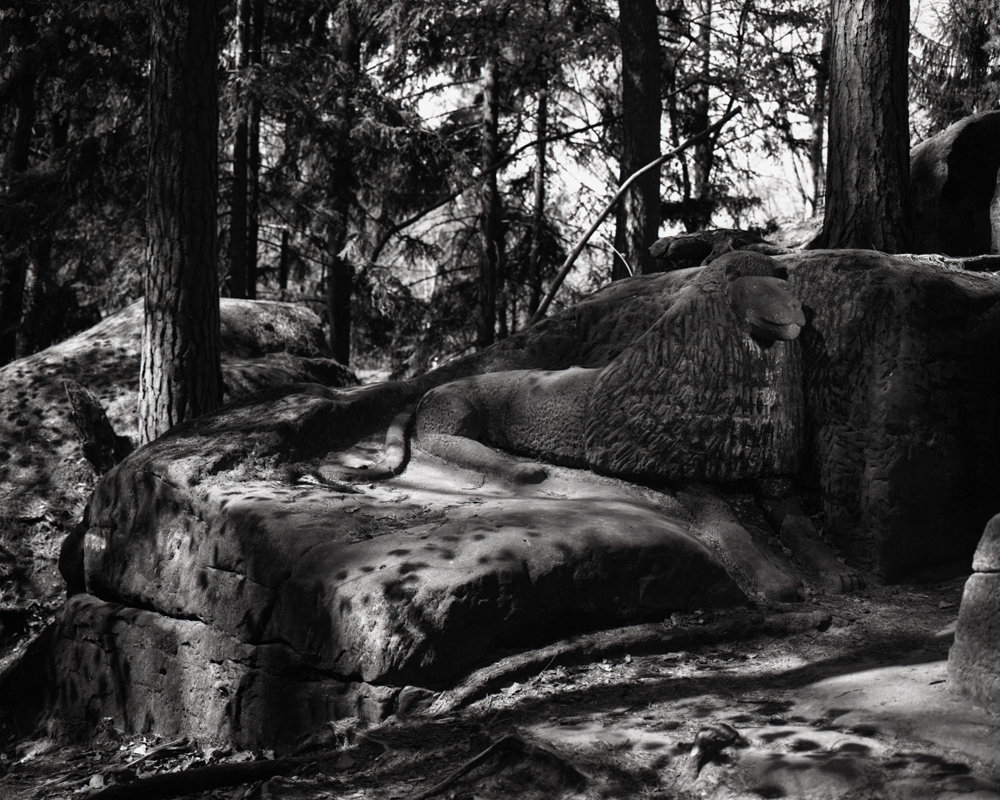

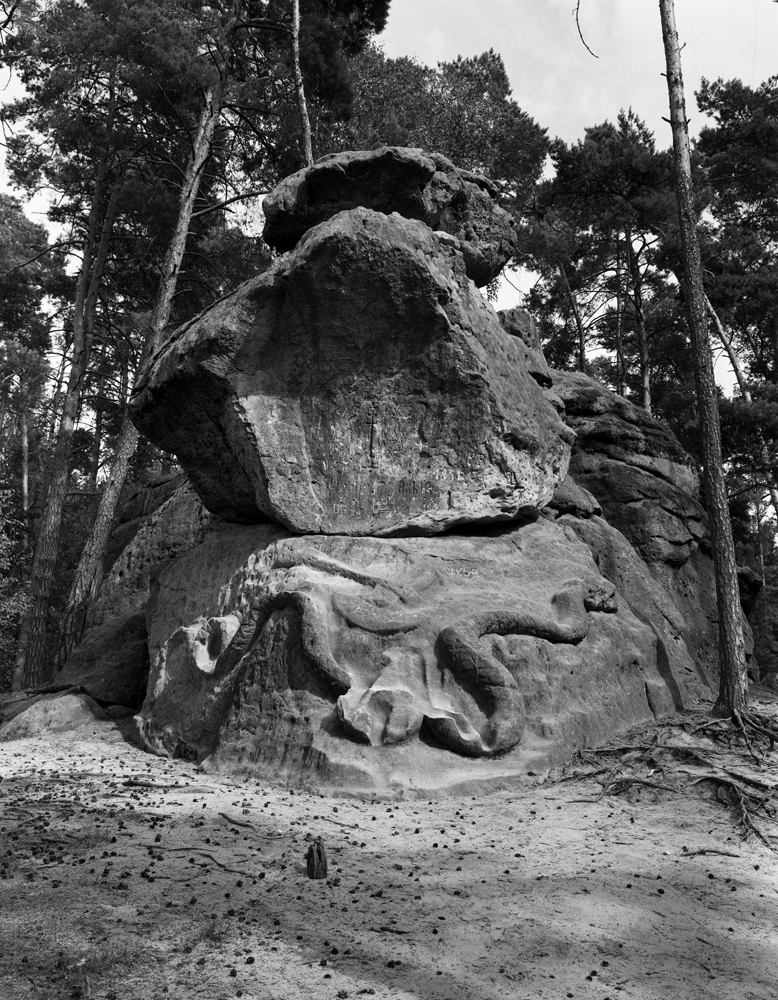

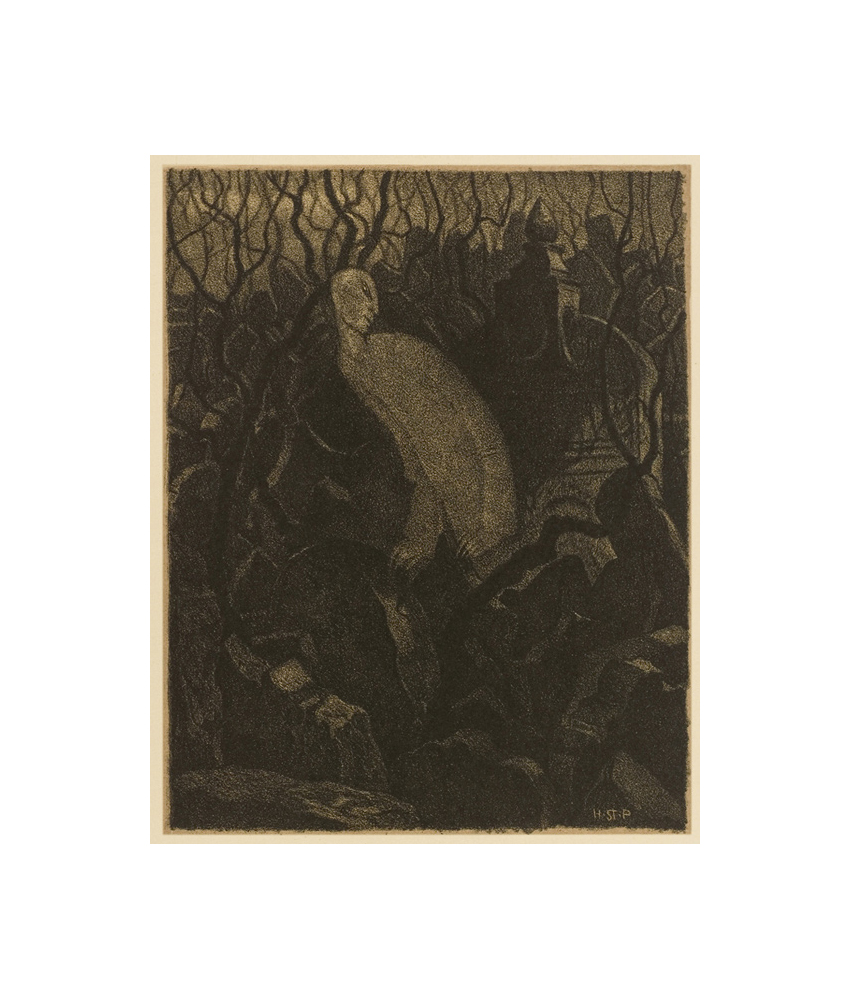

During the course of this project I’ve noted that the Czech Republic is home to a particularly large quantity of relief’s and sculptures carved directly into the rocks and stones of the landscape. These are predominant found in central Bohemia – the region found just north of Prague. Other examples can be found across the country, but it is the Bohemian landscape with its abundance of sandstone that seems to invite the most. Václav Cílek, writer and geologist, among other professions, observes that it is this sandstone landscape that reveals the special relationship of local people to nature, and describes it as “ a place where man, stone and tree meet and intertwine”. Cílek also notes that “through its medieval castles, stone sculptures and archeological findings, the sandstone landscape tells us way more about man than any other type of landscape”. I’ve photographed many places where both important artists and self-taught amateurs left their mark in the landscape by sculpting sometimes fantastic ornaments and scenes into the rocks. Let me start with one such place, the most sublime one of all of them but unfortunately also one of the most damaged and endangered ones – the forest near Kuks castle filled with statues by one of the Baroque’s finest sculptures Bernard Matyas Braun. These statues have been carved directly into the sandstone found in the landscape and were commissioned by count Špork (there’s a lot to say about this figure as well but maybe some other time and somewhere else). It is commonly known as Braun’s Nativity Scene, referring to his largest work – a full-blown life-size nativity scene featuring a grotto with water stream carved into the sandstone. The Nativity Scene is, however, not the only work found here, nearby there’s also a large fountain with beautiful but now heavily damaged sculptures and a huge statue of a rather controversial hermit named Garinus, who according to legend raped the daughter of a Spanish count, and as a punishment, he supposedly crawled along the ground like a beast, until he was forgiven. The statues were originally found in a thick forest in which many of the tree trunks were also embellished with various woodcuts and Biblical scenes accompanied by scenes from hell and rays of witches, revealing count Špork’s unsettled relationship with the Jesuits. Today, the area is waiting for possible funds from UNESCO or a similar organization that would facilitate their preservation for further generations. The forest around the works has very much changed and one has to employ a bit of imagination to understand the significance that the original presentation of these works (some argue that they could compete with Michelangelo in their mastery, only if they were carved into marble…) would have had in the past. Another place that I’d like to point out, is a farmhouse by Vojtech Kopic in the Czech Paradise (yes, there is such a place in Czech) and the rock relief’s that he created in a nearby forest during the turbulent historical events of the 20th century. Kopic had spent time at the farm both during the Czech occupation by Germany in WW2 and thereafter, during communism and the Russian hegemony. During these times, as a form of silent protest, he kept carving symbols of Czechoslovakian nationality and history into the rock behind his farm, creating an impressive number of works, quite naive in their appearance but important in their message and in their power. In this small area we can find everyone from St. Václav to the first Czechoslovakian president T. G. Masaryk together with their most famous quotes encouraging people to believe in their nation’s strength and in its moral laws. This man’s quest proves to me that art can be political but also therapeutic and a way of dealing with great injustice and that the most important examples of such art are often found not in the contemporary art galleries but in places where they’re least expected. The one last example that I’m able to fit in here, are a group of rather peculiar sculptures near a small town named Libechov. They are thought to be works of a sculptor Václav Levy, a 19th century pioneer of modernist sculptor, but some people (such as writer and historian Václav Vokolek – yes, yet another Václav!) believe that some of them might be older and are part of a masonic initiation trail. This is especially due to large quantity of masonic symbols that he claims to be misinterpreted by local people as folk references. I am not sure where the objective truth lies, but the works here are strange, and in their primitive-like appearance they point to something nearing the ancient sacred sites found in distant exotic places, leading one to question how they ended up here. It might be interesting to point out that one of the giant reliefs sculpted by Levy, commonly known as the Devils’ Heads, used to be the largest existing sculptural work up until Mount Rushmore was created. Who would have looked for something like this in the midst of Europe! P.S.: I am currently travelling and don’t have all of my files here but once I get to them I will upload more images of the above-mentioned locations.

Čachtice Castle and Elizabeth Bathory

Jul 04, 2016 - Tereza Zelenkova

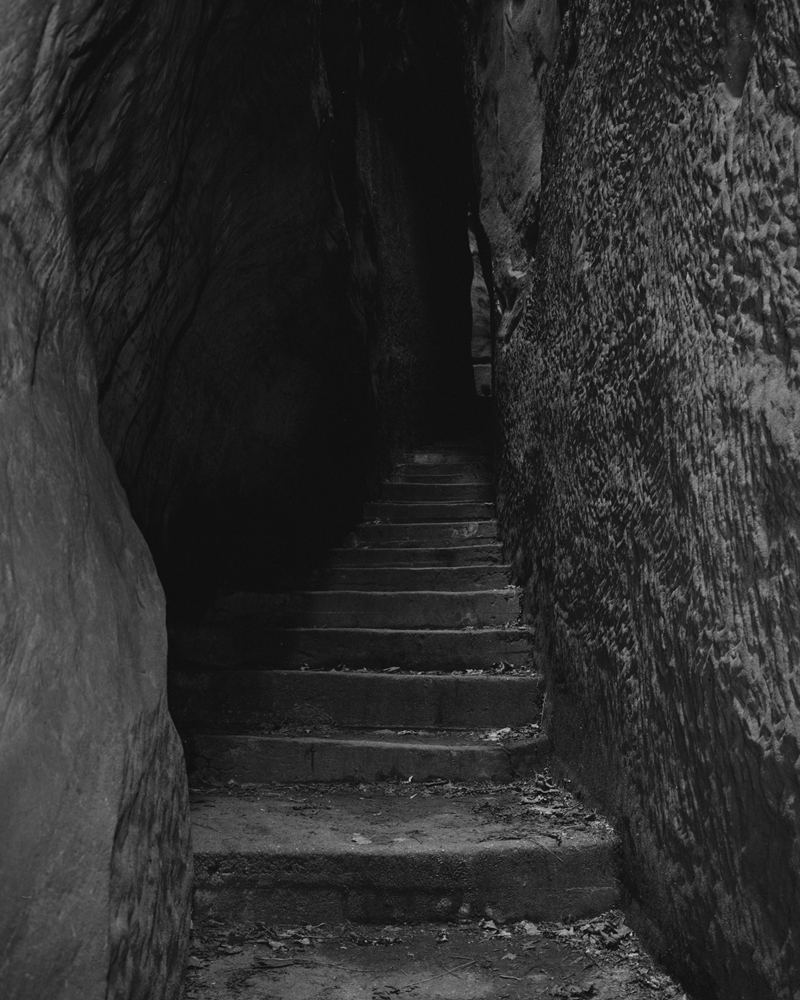

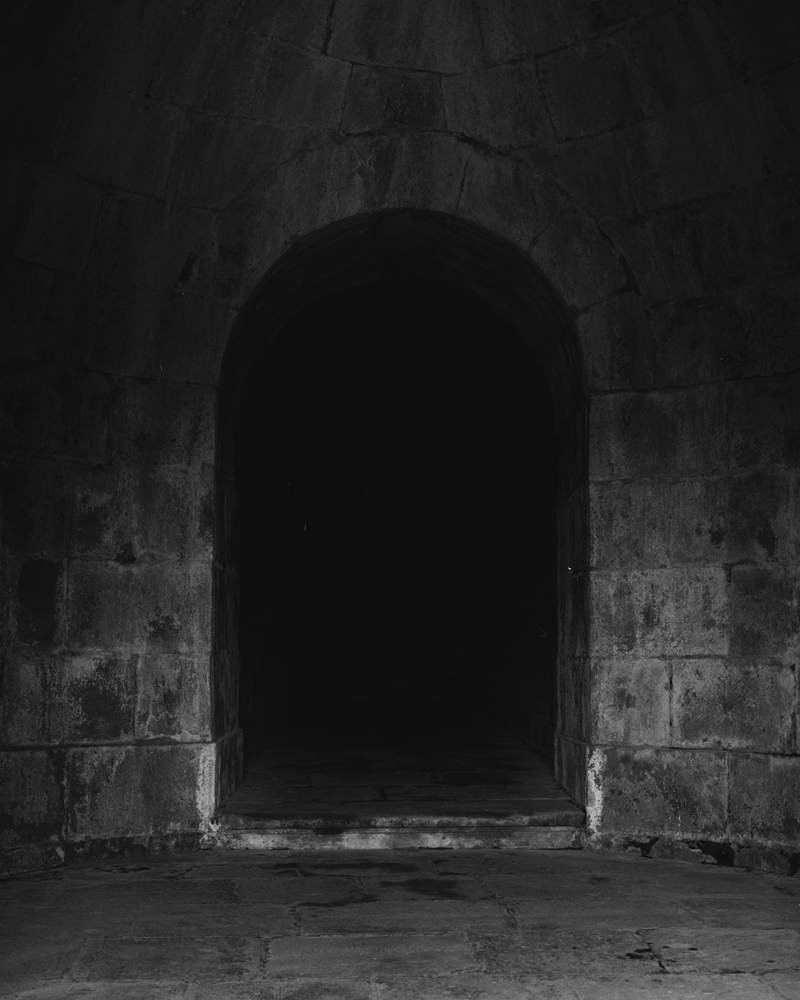

Aside from locations in the Czech Republic, I have decided to include some of the places found in Slovakia as some of the nations’ cultural and historical references are tightly bound, especially for myself as being probably the last generation that will remember Czechoslovakia as one country. One of the best known of these places is Čachtice (or Csejte) Castle, now a picturesque ruin but formerly the home to bloodthirsty countess Elizabeth Bathory (1560 – 1614). Elizabeth Bathory is thought of as the most prolific female serial killer in history. It is said that she had tortured and murdered dozens of local women, acts out of which she gained sadistic pleasure. She was trialed for these murders together with her accomplices who ended up being tortured and executed themselves, while the countess was imprisoned in her castle, in a room without windows, where she’d spent the last four years before her death. There are many folk legends surrounding these events, most commonly it is said that she would bath in her victim’s blood in order to maintain eternal youth.

One of the photographs that I took at the castle is an opening in the wall found in a room that used to be Elizabeth Bathory’s bedroom. It is claimed by the historians that the hole has always been there and that it used to be covered up with a wardrobe. As the opening leads into a rather large room with no windows and no other access, it is said that it used to be where the countess imprisoned and tortured her victims.

The figure of the countess as well as the castle itself is sometimes mentioned as one of the inspiration sources to Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the castle appeared in Nosferatu from 1922 (the main castle being the nearby Orava castle).

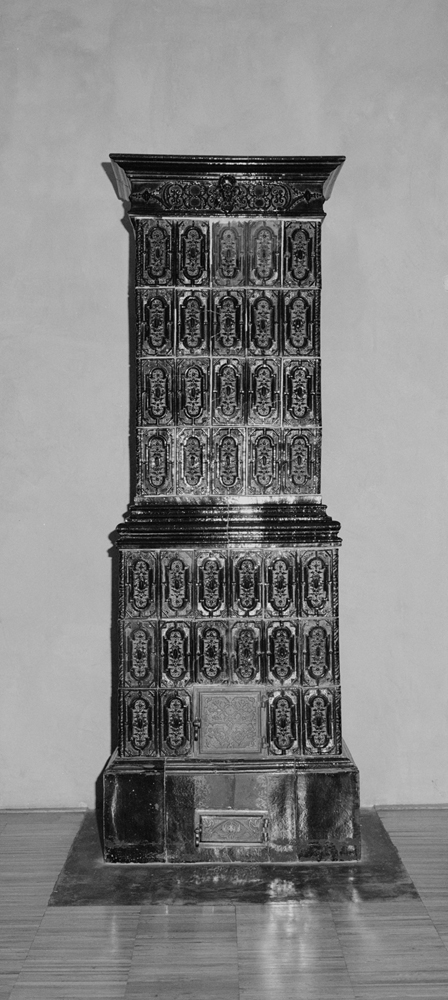

Čachtice castle is also setting to one of my all time favorite (Czech) films, The Mysterious Castle in the Carpathians. Based on Jules Verne novel, the film was directed by prolific director Oldřich Lipský and it features some amazing sets and props by Jan Švankmajer.

The Unseen

Jul 02, 2016 - Tereza Zelenkova

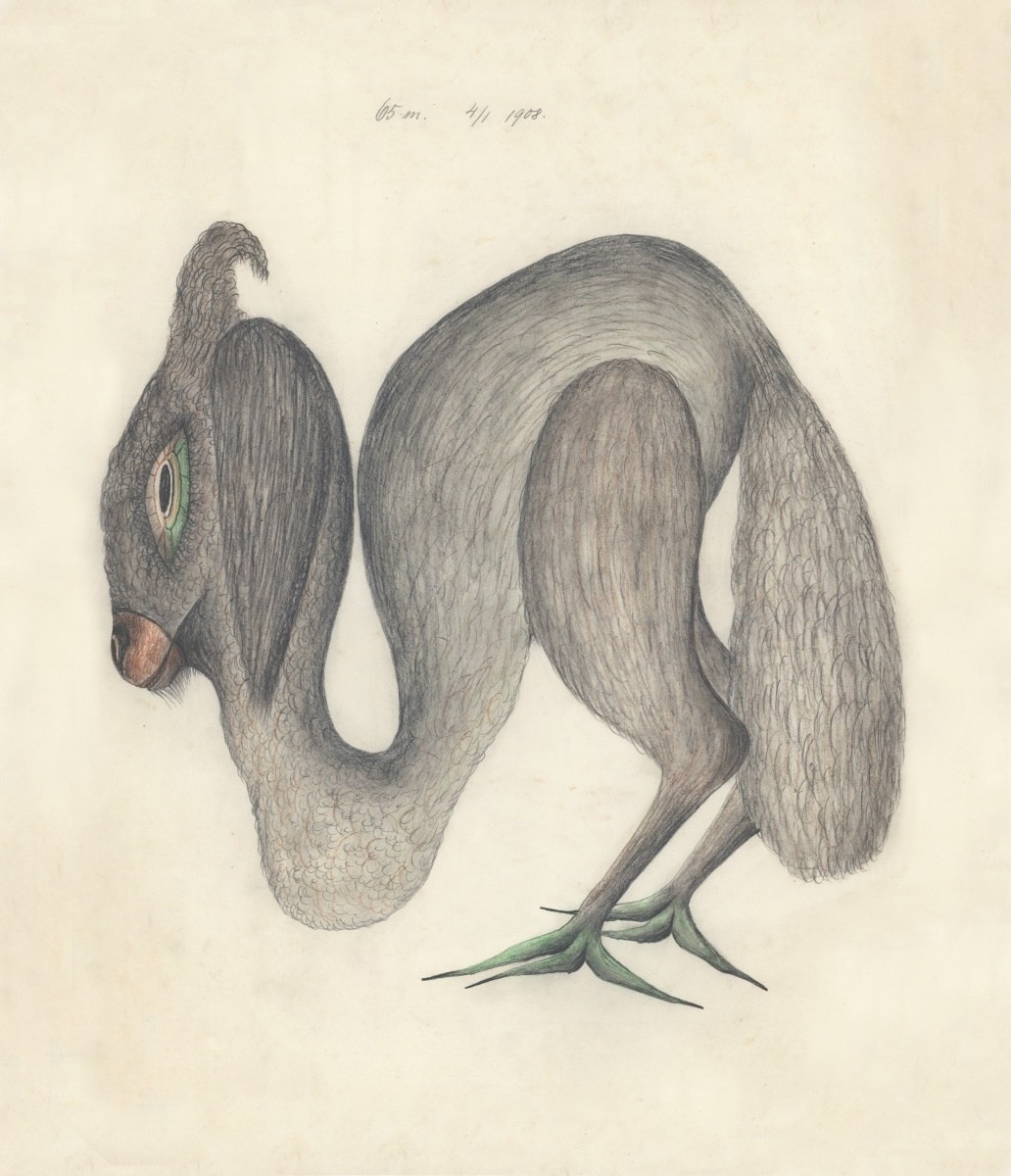

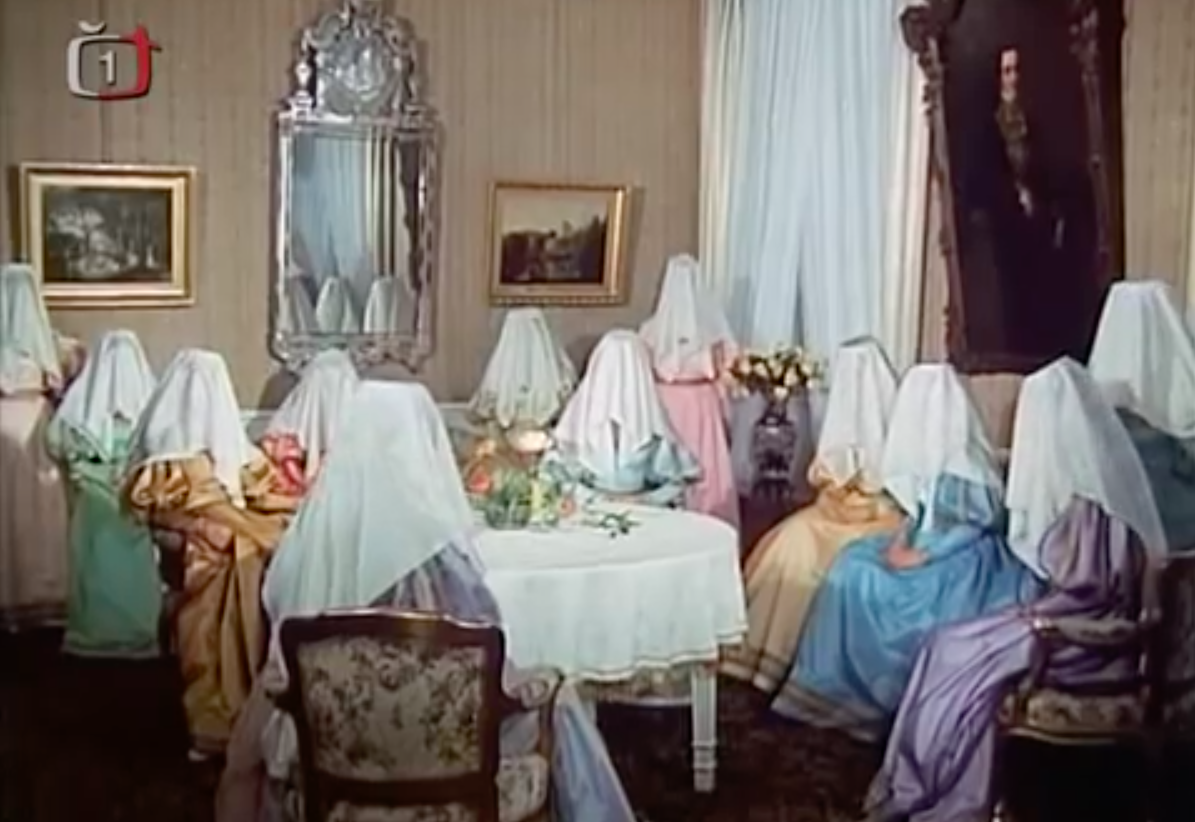

The first photograph I’d like to talk about is The Unseen. I get asked quite often how this sits within the series and what has been the inspiration for the image. Although I rarely stage my photographs, I had a quite clear vision of this particular photograph. It is an amalgamation of two themes that somehow merged in my mind and crystalized into this heavily distilled vision that I then went on to stage and photograph. Ever since I remember, I’ve been interested in photography’s peculiar relationship with death. It may sound like a cliché now but it can’t be denied that photography, similarly as a reflection in a mirror, offers the viewer aside of the image of his or her likeness also a glimpse of his or her mortality. Moreover, as Václav Vanek writes* when he talks about the loneliness and “deathly anxiety that we feel when, while trying to find a companion, we keep finding only a mirror image of ourselves and ultimately our death, which is always present in such mirroring”. Photography offers us both a promise of immortality alongside the reminder of our discontinuity. At the same time, due to its peculiar relationship with time, its strange stillness and minute detail it promises to reveal a bit more, something beyond the ordinary image of ourselves, or the everyday reality. It lures us to believe that it can see what’s unseen to the naked eye, that it can trespass the ordinary notion of time, and even blur the thresholds between the worlds of living and those long gone. Most of the people will be probably familiar with spirit photography, in which the 19th century society believed to find a way of communicating with their deceased loved ones. What’s interesting to note in this case is that the automatism of photographic medium was one of the key elements in this wide spread belief of photography’s ability to capture the world of spirits. Automatism of photography suggested the medium’s detachment from the cognitive processes of the human brain and its ability to tap into the unconscious, be it individual or collective. Automatism played a vital role not only in communicating with spirits, but also in early modernist art, especially in Surrealism. We have remarkable examples of automatic drawings, paintings or writings. In the Czech Republic, there’s a very special collection of such automatic drawings from the early 20th century, that however don’t come from avant-garde artists but from ordinary people found in one small region right at the foot of the tallest Czech mountain range, Krkonoše (Giant Mountains in English). From the end of the 19th century up until 1945, there seemed to be a golden age of Spiritism, that was however very unique to the region due to people’s relative isolation, living in the secluded farmhouses scattered at the foot of the mountains and meeting at each other’s houses for regular Spiritistic séances mainly held to bring back relatives who died during the war. The local people often used automatic drawing to receive hallucinatory visions from the other side and the collections of these remarkable drawings can be found in a museum in Nova Paka, but their notoriety goes well beyond the Czech borders as some of the finest examples of the so called Art Brut. So this is the first ingredient of my photograph. The second one is much more visual and comes as a snippet from a Czech fairytale Goldielocks, written by one of the most famous Czech 19th century writers, Karel Jaromír Erben. The scene that I used as a base for my photograph comes from the 1970’s version of the tale and it is a moment when the main hero needs to recognize Goldielocks, the princess with golden hair, amongst her twelve sisters, even though their hair is covered with a veil. I’ve always found the scene rather surreal and it immediately connected for me with the popular image of ghosts. There’s also something ritualistic and esoteric about the whole thing. * In an introduction to a J.J. Kolár’s short story At The Red Dragon’s in a compilation of Czech Romantic prose.

Beyond The Image

Jul 01, 2016 - Tereza Zelenkova

mg src="https://dergreif-online.de/www/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/01-Aderspach-rocks-560x700.jpg" alt="Aderspach Rocks" width="560" height="700" class="aligncenter size-large wp-image-67681" /> As I continue with my practice, the stories behind each photograph are becoming increasingly more important. Although I’ve always employed a certain aesthetic that often relies on ambiguity as one of its key elements, it is impossible for me to think about any of my images without a concrete thing or story that it either represents or references. Every image I take stands for something that holds some kind of importance for me that goes well beyond the aesthetics or technical aspects of the photograph. Sometimes I even question whether there’s a possibility of anything like an independent photograph . . . In my ongoing project, The land with the secret heartbeat (this is still a working title and actually in Czech is sounds much better, haha), I am trying to work with history, local legends, cultural references and literary works bound to the local landscape. At the same time, I’ve given free reign to my imagination to fill in any gaps or use fragments of various stories to create visual interpretations. Moreover, it’s clear now that I might even add some stories of my own, because that’s exactly the way legends are created. In the next few days, I’ll try to post some of the stories behind my photographs. Please don’t expect any texts of literary worth; these will simply be rough sketches and snippets from my research, but hopefully these will shed some light on what lies at the heart of this project.

Prague

Jun 30, 2016 - Tereza Zelenkova

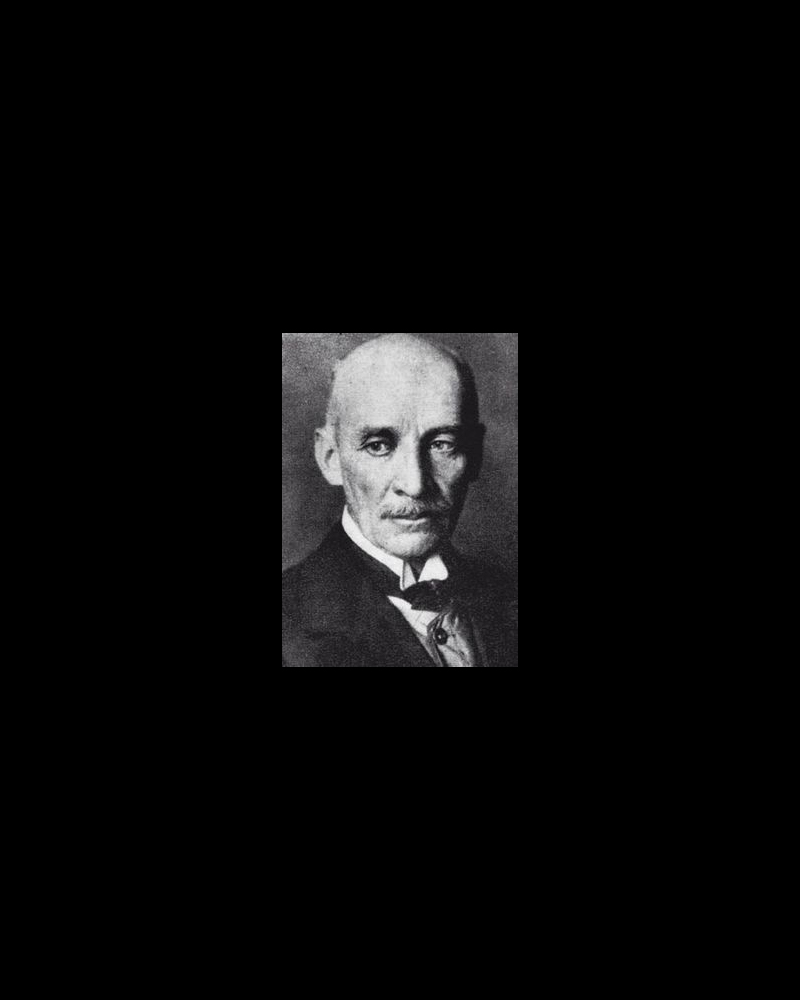

Currently I find myself in Prague, where I’ve given myself an uneasy task of portraying the city’s genius loci without falling into the trap of cheap thrills and postcard aesthetics. Working on a project that has to do a lot with something that I perceive to be distinctly Czech, it is interesting to note that most of the people who I associate with the emblematic image of the Czech capital are of German (or Germanic) origin. Starting with Rudolf II, who elevated Prague to the capital of his empire and defined the image of Prague as a city closely associated with alchemists, astrologers, astronomers, as well as eccentric artists, this city’s dark heartbeat has been heard loudest through the voices of its ethnic minorities. Today many people associate the city with Franz Kafka, however only few of the tourists have probably read anything written by this prolific writer who’s legacy goes on in works by literary masters such as Borges, Burroughs, and Orwell. For me, Prague is the city of Gustav Meyrink’s mystical tales where he talks about the city’s secret heartbeat that “washes away all the names, creating myth after myth”. Meyrink’s Prague is the city created by seven travelling monks from the Orient, the city that lies on the threshold (Praha is derived from ‘prah’, which means threshold) of different worlds or realities, and especially it is the city forever haunted by the specter of Golem, the artificial man thought to be created by Rabi Löw in the 16th century. For Meyrink, Prague is inhabited by peculiar characters such as the old watchmaker, white Cacadu, or even the author himself who claims to be transmuting base metals into gold with the help of nothing else than old shit found under the cobbled streets of the ancient metropolis, serving him as the philosophers stone. Recently, it has been a great discovery for me that the original death mask of Gustav Meyrink is in existence, and I will be lucky enough to photograph soon. The question however remains, how to photograph a city whose image is more than anything else felt. Yes, there are beautiful places and views but what makes Prague the dark heart of Europe is that secret heartbeat that makes the city pulse with strange energy that can be felt especially during the quiet nights when all the Segway tours finally disappear and the only inhabitants seem to be the many statues found on its ancient bridges, monumental portals, and even in the quietest of the city’s corners near the old monasteries, we can feel that we’re never quiet alone. It is a great shame that parts of the city that would now seem as some of the most interesting ones, such was Josef, the old Jewish ghetto, have been demolished, and the ones that still remain are filled with tasteless souvenir shops and fast food kiosks. It makes me think of a quote by another German writer who was born and wrote in Prague, Johannes Urzidil: “(It is the time) that creates value. At least as much value as it destroys. Remember this.” I am not sure how much value we create these days, let’s hope that this equilibrium hasn’t been disrupted with our contemporary love for fast, cheap gratification. – Tereza Zelenkova