Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

Para-Phrase: Eleonora Agostini & Sian Bonnell

Mar 21, 2020 - Gita Cooper-van Ingen

‘agency is not aligned with human intentionality or subjectivity…Crucially, agency is a matter of intra-acting; it is an enactment, not something that someone or something has’. (Barad, 2007: 177-8)

The garden is neat and tidy, bounded by metal fences and a large steel gate to the front – and at the back a clipped hedge frames the lawn. The front and side of the house has paving all around that is mostly weed-free. A curved path leads to the white newly painted summer house at the end of the garden. It has no windows, just a set of half-glazed double doors with closed curtains inside. Above the door is a decorated lintel like a pie crust and above that the roof extends into a canopy with a carving of a miniature house and tree fixed to the apex and painted the same as the building it decorates. On each side of the roof run two gutters allowing the rainfall to drain. The rain comes on so suddenly and hard that it bounces upwards from the roof, giving the sun no time to stop shining.

An assemblage of parents, uncle, aunt and two step ladders. This image says circus and spectacle. Not so much a portrait with ladders but an intra-action. The ladders and humans equal to each other – three of the humans posing exactly like ladders. A reminder of the technicians at art fairs who are attached literally to their own step ladders. Their legs are strapped in the same position as Father so that they walk with the ladders acting as extensions of their legs like strange stilts, moving their ladder-legs in a scissor-like sideways motion that is quite strange and magical to observe. Literally a human-machine.

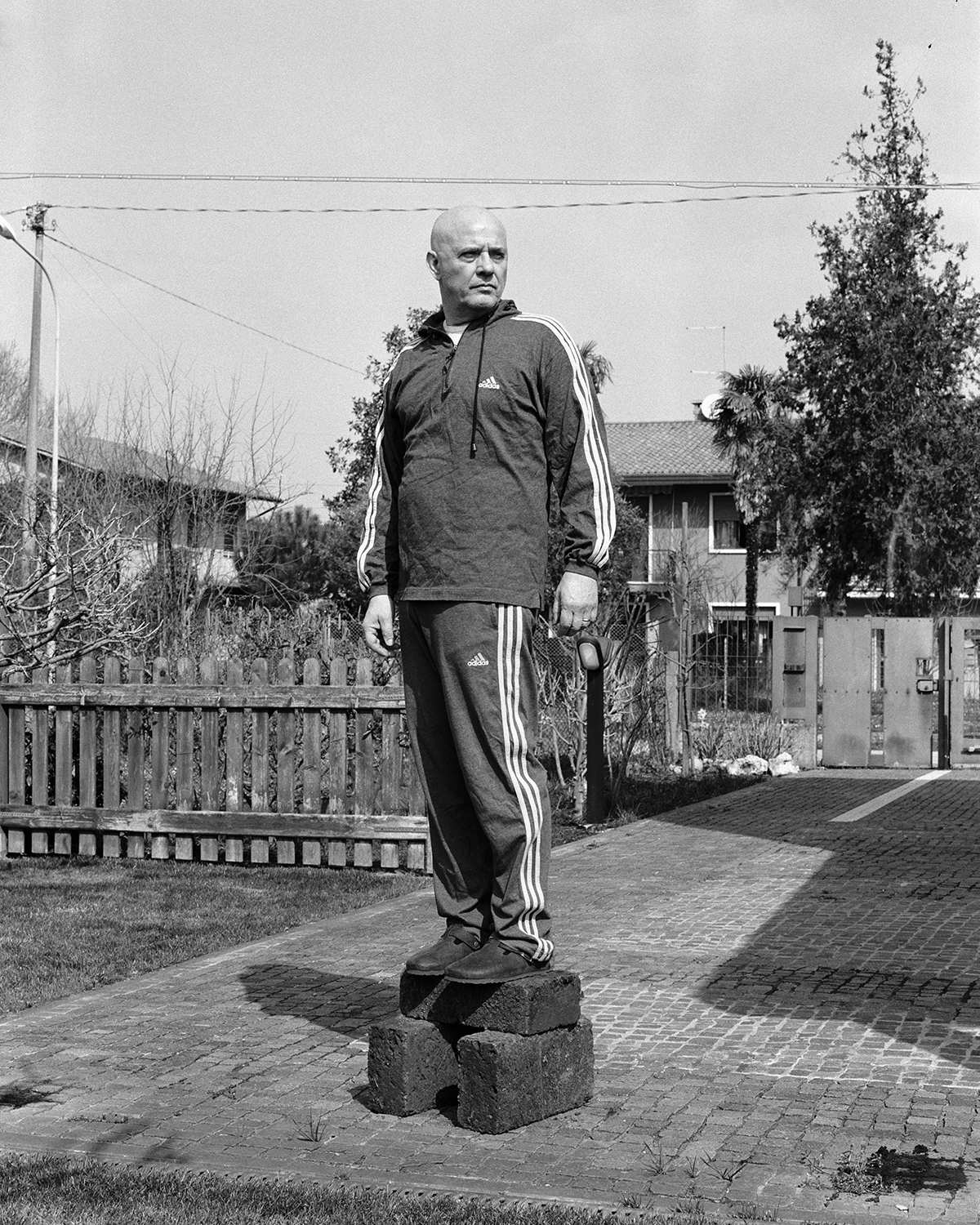

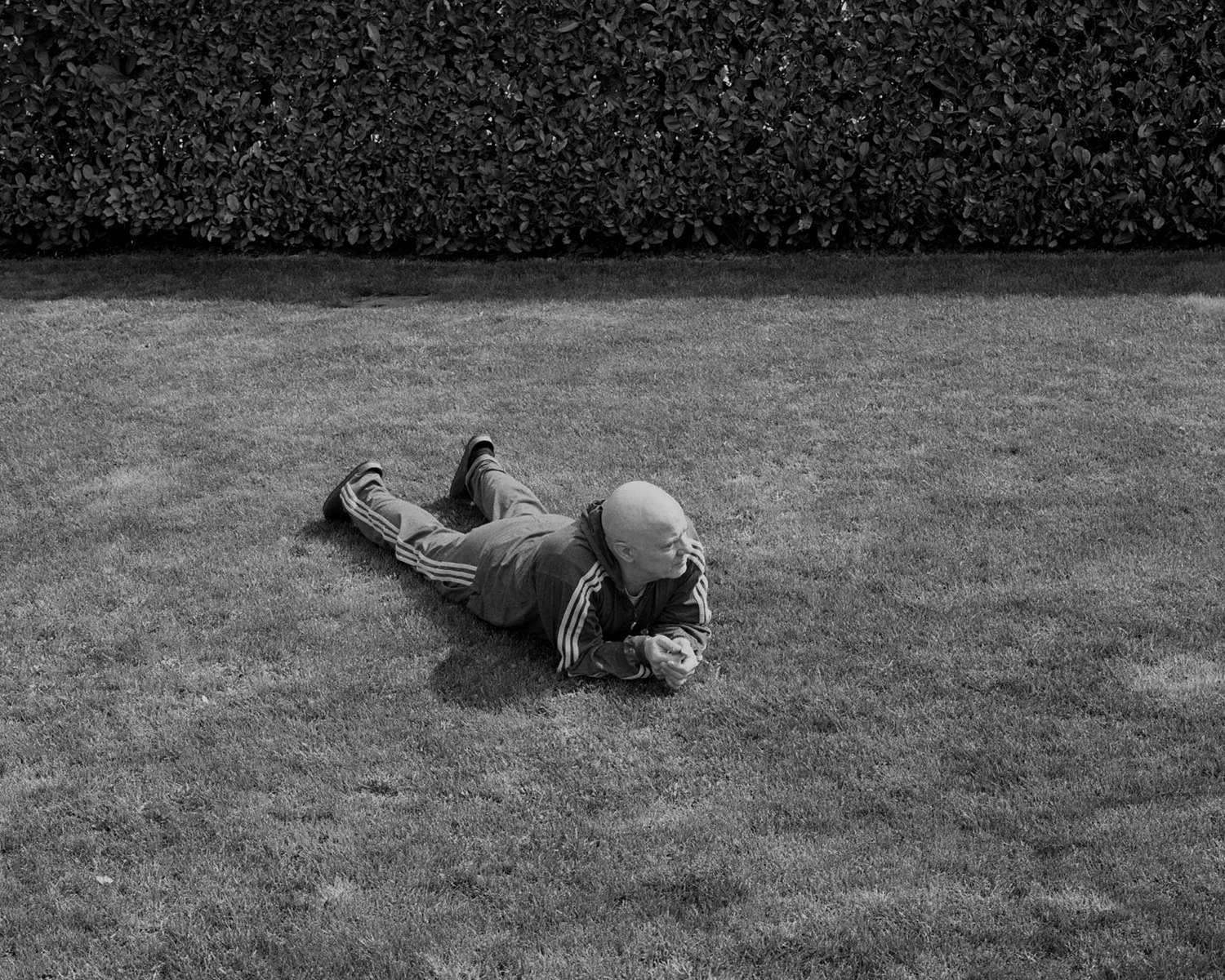

Wednesdays were always difficult days, the mid-point of the week, if the week wasn’t good – and it invariably wasn’t. Early closing day. So that the town was dead every Wednesday afternoon. Walking home was lengthened by looking in the shop windows, strangely, she only remembers the days being long, hot and sunny. She had her favourite window – the Chemist’s with three enormous glass bottles, like urns each with coloured liquid in, blue, red and green. The windows she disliked were the Bookshop and Wool-shop with their horrid yellow film over the windows making everything look ill. At home, her parents are on the grass. They do this every week. Her Mother is walking on top of her Father, in a strangely compelling ballet. He doesn’t seem to mind at all, although the weight of her Mother removes the agency of speech. In this image the grass is intra-acting with Father, he is literally melting into it, he could be wearing red or green, either way it does not really matter because he shares the same tonal value.

The window has a grille on it but it’s too late, the objects have escaped – piled up refugees; everything equal but some more equal than others. It appears quite a natural occurrence but the arrangement is somehow artful with the objects stacked in a pyramidal structure. We know though that this is pure theatre – the table-cloth being the cue. Indoors, the kitchen is owned and fixed. Everything is in its rightful place in drawers, cupboards, cabinets and shelves. A hierarchy and an order exist there that cannot be subverted. But the theatre of outdoors is another space: a space of agency. The stage is set with a clean, pressed tablecloth. Kitchen objects purposely piled up in a semblance of order; everything is clean and shiny and all the packets of perishables are unopened. One is tempted to think that those objects have landed themselves there, as if in the middle of the night they all developed legs and marched out of the kitchen. ‘Beware domestic objects’ said Claude Cahun in 1936. This is the ‘angolo cottura’ or kitchenette. All is chaotically ordered but in a disorderly way. The objects releasing themselves from the kitchen cabinets. She is always amused that the heart of government is called ‘cabinet’.

He stands against the whitewashed wall with a pile of freshly laundered towels, holding them out before him echoing exactly the way her mother held out her new baby for the photograph. Apart from two fluffy ones, the towels are old and worn, some have textured patterns on them that play with those of the wall behind them. There is something quite arresting about this pile of towels demanding to be admired. It is an act of wilfulness to photograph a pile of folded towels. They have been de-contextualised from their natural domain – banished from the bathroom, the washing line and the airing cupboard. We are forced now to regard them as if they were a portrait of a person or an arranged still life. In a way they are both of those things since most of the person has been removed, leaving just the arms to act as the plinth or armature for this domestic sculpture. We are made to acknowledge the agency between these towels and their equality with that pair of arms. The democracy of the monotone image helps with this

The camera is behind him now, looking up and we are shown the beautiful textures of his shiny shaved head, a contrast to the soft washed marl of his T shirt. Suddenly the head has become something else; we recognise it as the human head that it is but it is also part of something other and we begin to see the agency of the head intra-acting with the clothing and the sky.

‘The law of the “proper” rules in the place: the elements taken into consideration are beside one another, each situated in its own “proper” and distinct location, a location it defines. A place is thus an instantaneous configuration of positions. It implies an indication of stability.’ (de Certeau, 1984: 117). These photographs question space and place and in turn, the shifting politics of the domestic around notions of control and power. Are the parents playing along with her, content in allowing her to control them? She is reminded in the most physical way of that moment where they as older parents realised that the ground had shifted and it was not them anymore, leading things. Despite the humour these images generate feelings of unease; they are funny but as in all successful comedy a discomforting aftertaste lingers. The home has literally lost its place, becoming a space of disruption ‘a practiced place’ (ibid: 117). There is madness here and absurdity; the outside is playing at being the inside, in a scenario that parallels Lewis’s Looking Glass. The use of monochrome and deadpan allow the imagination to operate. Narratives emerge she is reminded of Virginia Woolf and Agatha Christie an odd pairing. Certainly, a murder will be committed at some point… It is all an illusion; everything must surely return to normal soon?

The parents stand before the house, between them is a vast pile of chairs and soft furnishing reaching almost to the upstairs windows. There are shadows behind but these are not caused by the sun. They appear enchanted and entranced; have they have been hypnotized or put under a spell? They speak in a monotone repeating over and over ‘there’s no place like home, no place like home…’ as they circle the assemblage. They cannot stop, they have been doing this for days. Thank goodness she came home.

Eleonora Agostini (b.1991) is an Italian artist and photographer based in London.

Her last body of work “A Blurry Aftertaste” has been exhibited as part of Bloomberg New Contemporaries (Leeds Art Gallery, 2019 – South London Gallery, 2019/2020), With Monochrome Eyes (Borough Road Gallery, London 2020) Dieci x Dieci (Gonzaga, 2019), Looking On (MAR, Ravenna 2019), Forever/Now (Format Festival, Derby 2019), On Making (National Museum of Gdansk, Gdansk 2019), among others.

“A Blurry Aftertaste” was published as a book form as part of Paper Journal Annual 2019.

She graduated from the Royal College of Art MA Photography programme in 2018.

Eleonora’s practice encompasses photography, performance, sculpture and moving image and is driven by her interest in the reconsideration and redefinition of the every-day. Whether it is through the fabrication of scenarios for the camera or the documentation of anti-monumental activities, she is interested in finding a possible fracture within our socially constructed rules and the spaces we inhabit.

Sian Bonnell is a UK based artist, living and working in West Yorkshire. She is currently Reader in Wilful Amateurism in the School of Fashion, at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Her work is held in many public and corporate collections notably, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, the Ransom Center, Texas and the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris.

Research is divided into many strands concerning photography and its relations with performance/performing for the camera; sculpture/the object and the camera; the dissemination of the photograph, with regard to curation, publishing and the book and its relations with other disciplines such as medicine and social science.

Para-phrase is an online project that commissions pairings of images and text, where a photographer is invited to submit images and a writer is invited to respond to the selection. It offers a platform for exchanges and responses between artists, writers, and curators whose work produces and promotes the discipline of lens-based media. Para-phrase draws on the multiplicity of artistic processes and aims to encourage their exchange. It supports a wide range of voices from an expanding network of practitioners open to collaboration and exchange and shows that the outcome reflects the many, varied approaches of how to interpret both image and text. Both the acts of writing and photographing attempt to interpret the world, to decipher the symbols, figures, data, complexities of our respective realities.