Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

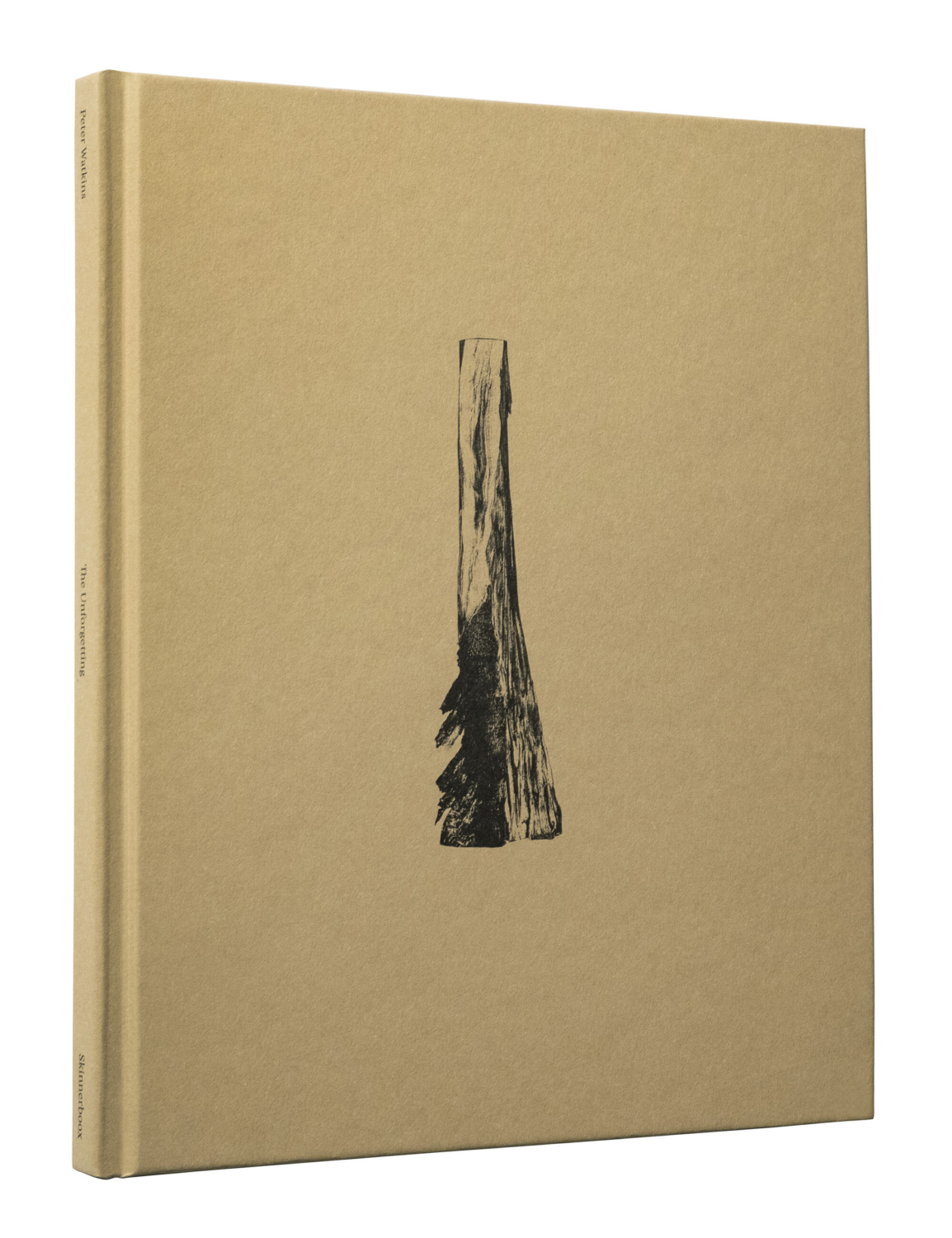

Peter Watkins’ “The Unforgetting” featured by Zak Dimitrov

Mar 12, 2020 - Zak Dimitrov

Most modern-day coins have ridges as part of their security features and the reason behind this can be traced to ancient times when precious metals were the standard. Thieves used to take small shavings, hardly noticeable, but enough to accumulate over time. In a similar vein, a photograph takes something from its subject, in a subtle but irretrievable manner – there is a saying that a portrait is like a thin layer of skin stolen from its sitter.

“In front of the photograph of my mother as a child, I tell myself she is going to die. I shudder like Winnicott’s psychotic patient, over a catastrophe which has already occurred. Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.” – Roland Barthes

There is something enormously surreal about looking at photographs of the dead, even more so if it is one’s own mother as a child. The overpowering sense of being privy to a secret that she is perhaps unaware of – she will be dead all those years later – but also the difficulty imagining that the mother was once upon a time a child too. Life before one’s birth, this land of truths too far away to comprehend, and present colliding. Death is the only certainty in our existence. Photography, intrinsically related to death at its core, is a depiction of “what has once been”. The medium is ultimately about the past and one of its original purposes, when it was invented, was the preservation of people, objects, memories. It was not only a statement that what was depicted happened in reality, but also photography manifested the realisation that nothing endures for eternity. Therefore, photographing and capturing what was most precious was a melancholic act worth pursuing. Wrinkles slowly appear on once handsome faces, which slowly turn into dust and vanish, our beloved parents and grandparents leave us alone always much too soon.

The mother is a pivotal figure as life begins inside her body. Not only does she give physical birth but she also nurtures and protects – the term “mother-figure” exists for a reason. A number of photographers have recently included either the mother as a person or motherhood as a concept in their work. Paul Graham’s Mother, for instance, is a calm and quiet tribute paid to his mum who is now approaching the end of her life. Sophie Calle’s Rachel, Monique…, on the other hand, is a conceptually more complex project, including diary pages, performance created specifically for the camera and archival imagery of her recently deceased mother. The Unforgetting by Peter Watkins has a slightly darker tone to it – his mother did not die of natural causes, she decided to end her life. It is said that grief and the longing for somebody who is no longer here changes a person and their world. Psychology and science have provided various mechanisms for coping or overcoming grief; photography provided Watkins with a path and a project that would help him reconnect with his lost parents. The body of work is deeply mature, sophisticated and far more polished than one would expect from a photographic project created by a man in his twenties.

Peter’s father died in 2006 and it was this event that stirred the feeling of time slipping away in the young photographer. With both his gone, he realised that the opportunity to talk to his relatives about the events surrounding his mother’s demise were slowly vanishing. During his MA at the Royal College of Art he embarked on a journey and filmed, interviewed and documented places, objects, and people related to his mother in her homeland and, in particular, the beach where her body was found. Developed over the course of nearly a decade, the work grew, developed and matured as it became predominantly photographic. Curiously enough, when Watkins showed the pictures at his final MA show, he provided no contextual information, which seemed fitting with his interest in the fallibility of memory, both collective and personal. “I was always very careful about what I was saying and sensitive to those implicated in the process”, he tells me. It was not his original intention to present such deeply personal and cathartic work to an audience. “The idea that this would all somehow become public happened in stages.

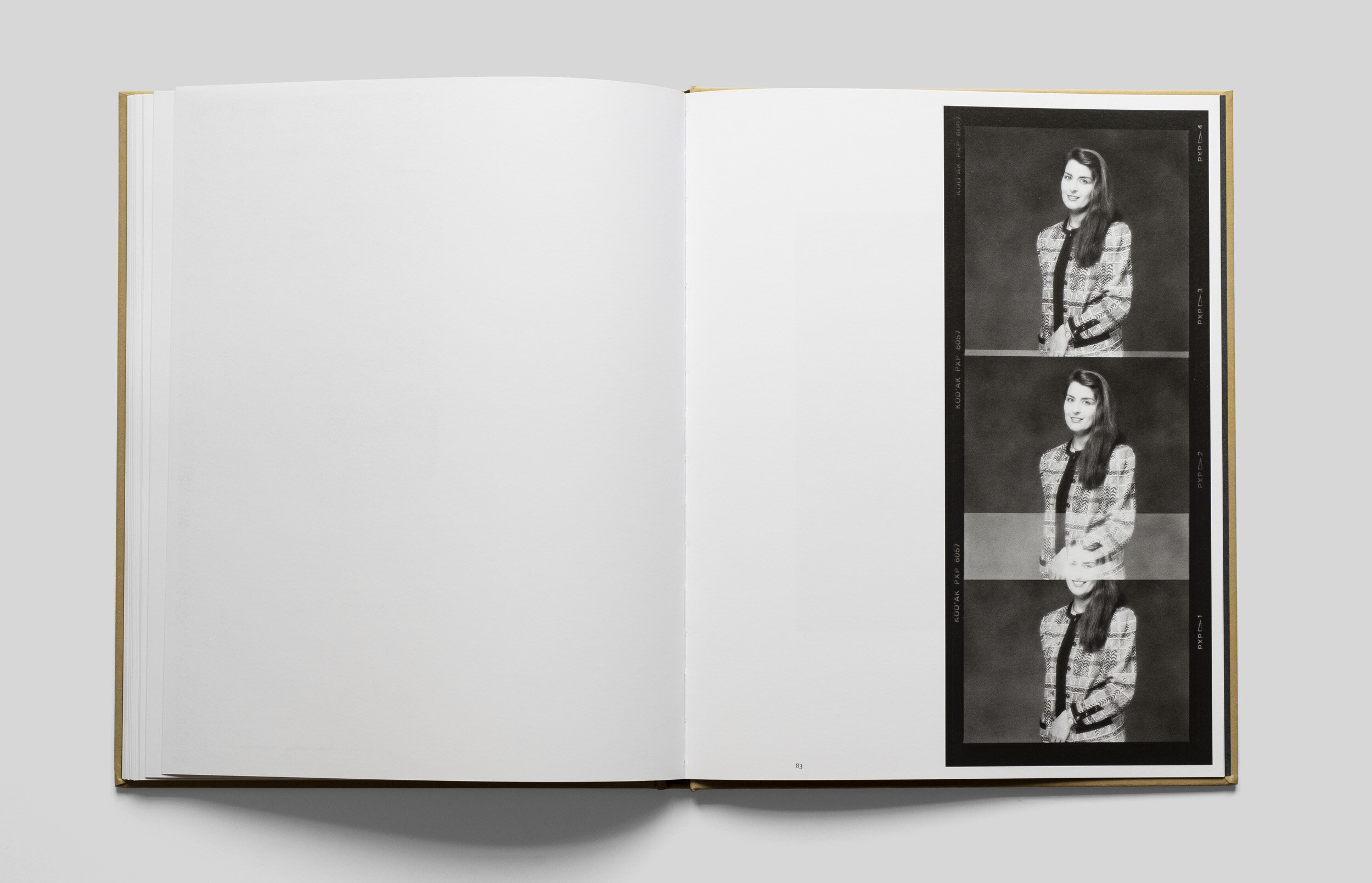

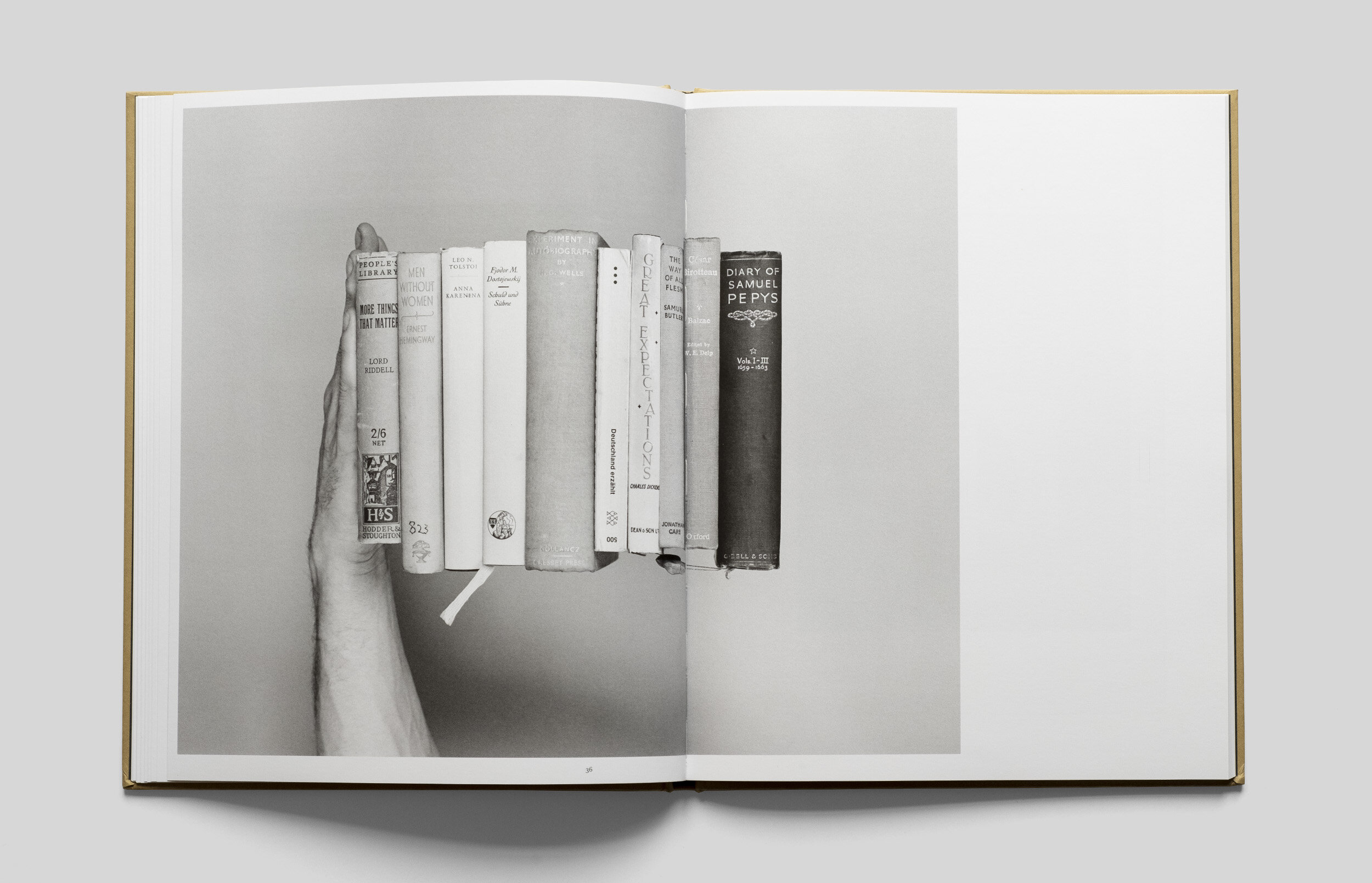

A vertical triptych of the same image of a smiling girl in black and white wearing a hairpin; multiple reels of 16mm film; a portrait of a man with his face half-hidden from view, circular scars on his body, holding a cable release ; a piece of timber with a small printed photograph on top supported by the blade of an axe; wood; more wood; a silver-haired woman with her back against us; Russian books; English books; German ones too; German newspapers with references to schizophrenia; disorientating writing, back and front, layers and layers of it; a pile of neatly stacked slabs of wood a few pages later; pictures of pictures evoking nostalgia and the memory of what has once been; a bag juxtaposed with a list of its contents treated as evidence. Overpowering sadness and the sense of longing grabs the viewer, but also curiosity as the pictures themselves do not attempt to provide answers – they are an open-ended attempt to piece together the traces of a life cut short.

Notwithstanding the fact that the images are powerful in their own right, they are accompanied by three different pieces of text towards the end of the book. There is the text on the back cover which references the images, provides titles and dates when they were taken. There is also a leaflet with an interview and installation shots of the images in situ. Finally, there is the list of the contents of Watkins’ mum’s bag when her body was found. The booklet is particularly relevant as it shows the project in a different form – objects, sculptures and photographs – however, the core meaning remains the same. Moreover, it is a separate element in the sense that it is not part of the book itself, which is a nice touch.

The photographs resemble documents, a representation of thought and proof that Ute existed. Some bear a staged element, particularly the ones including the photographer’s own body in the frame. Some are so slick and neutral that they echo the appearance of a monochrome still life painting. There is an important distinction to be made, however, between a photograph and a painting. While the latter is created out of nothing but the painter’s vision and imagination, the former is carved out of the real world and is a physical imprint, a remnant of its referent etched on a light-sensitive surface. I cannot help but feel that one of the many functions of The Unforgetting, to Watkins himself at least, is a collection of mementos from his mother and her life; a private object for him to hold by, perhaps a container or a time capsule, to one day pass onto his daughter, ensuring Ute lives on.

A collection more precious than a gold coin.

Text by Zak Dimitrov, 2020.

More information to Peter Watkins’ project can be found here.

Zak Dimitrov is a London-based photographic artist. After successfully completing his art foundation in photography, he moved on to study BA (Hons) Photography from which he graduated with First Class Honours in 2015. He recently completed his MA in Photographic Arts at the University of Westminster, further developing his work on memory, mortality, loss and time.