Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

Q&A featuring Diana Poole

Diana Poole is a Zürich-based art advisor specialised in photography. She supports clients through their collecting journey, working closely with artists, galleries, auction houses and institutions. Diana also curates exhibitions and organises art events, online and in person.

Diana, can you share with us how the pandemic has changed the photography market, what new trends might be emerging and how you see these developing?

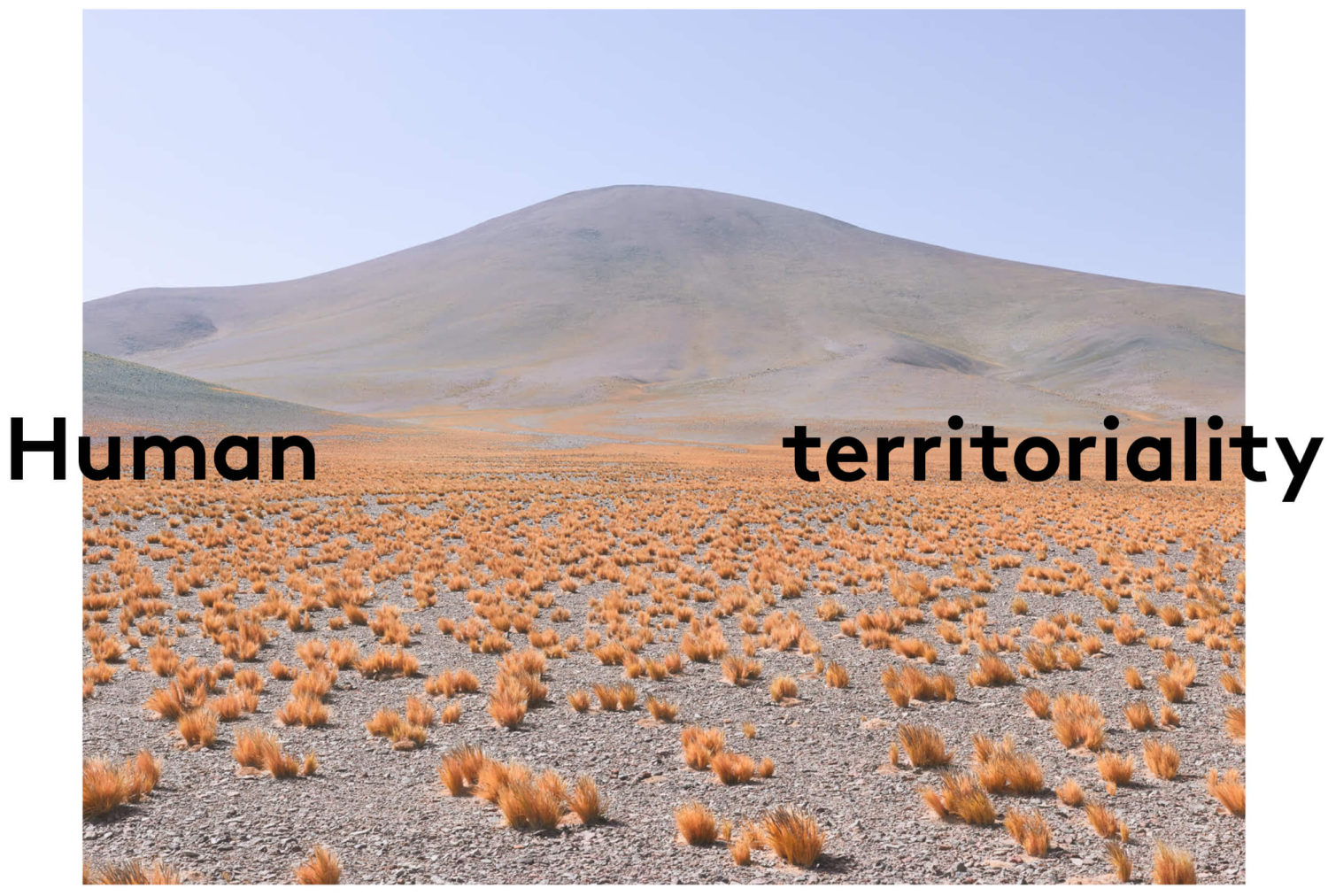

Today, the art market is more accessible and collaborative than ever before. We’ve seen unprecedented technological advancements in an industry previously lagging in this arena, with sophisticated online viewing opportunities through virtual galleries and online viewing rooms (OVRs). Auction houses improved their online experience via digital catalogues and data sharing. And through this came an increase in confidence with buying photography online, especially at higher price points. For example, Robert Frank’s iconic ‘Trolley – New Orleans’ (1955) sold at Phillips for nearly half a million dollars in 2021 via an online bidder. In fact, Phillips saw its online sales surge from around one third of total volume pre-pandemic to as much as half today. I certainly witnessed this with clients acquiring a whole range of works online during the pandemic, from contemporary positions such as Roger Eberhard’s ‘Human Territoriality’ (via my online exhibitions) to historical work such as Helga Paris or Irving Penn – and it continues now.

Obviously, there’s nothing like seeing artworks in person, having that physical experience and understanding the subtleties of a piece. It can be risky buying online, especially if coming new to an artwork or with earlier vintage material, given the variations in paper and print runs. It’s more important to take care and do our due diligence relative to authenticity, condition and quality.

Another consequence of digital acceleration has been the democratisation of access and information, which has increased knowledge sharing and reach. Today we’re able to meet artists in their studios or curators in museums across the globe via digital conferences and virtual events, which opens a vast new space for collaborating. There’s greater transparency, propelled by art fairs going online at the beginning of the pandemic and prices for artworks being made public. New regulations and younger buyers expecting clearer information means we’re seeing traditional barriers broken down, and to some extent the reduction in importance of more established gatekeepers. The NFT market, which exploded after the multi-million-dollar sale of Beeple’s NFT at Christie’s in March 2021 was extraordinary and shows just how things have shifted.

More generally, I’ve noticed an openness to work across different disciplines, and a strong desire to co-create. Perhaps coming from the powerful community building happening online, or from a greater need for meaningful connection after this period of isolation – realising that we can do more together than individually. I’ve found this very energising.

What do your art advisory activities involve – and what do you feel is the most interesting part of your work?

My business is divided into 2 main parts. On one side is the advisory, where I support collectors in building and growing photographic collections. On the other is working with artists, galleries and curators on content creation and curatorial projects.

The two parts often overlap and have interesting synergies, especially when I think about the curation of collections for clients, exploring their vision and what story they wish to tell through collecting. Accessing new ideas and thinking through exhibition projects, alongside new artist discoveries and collaborations, is not only a learning experience; it sometimes enables me to push a collector to look beyond their initial scope, maybe to more challenging artworks, or a broader historical view with institutional relevance and references.

For the advisory, I source emerging and established artworks from galleries, auction houses, artist studios or estates, which means I’m constantly having diverse and enriching conversations. This might be with a photo specialist at an auction house in New York, going deep into a particular print they have coming up for sale, or a dealer in Tokyo on their holdings of post-war Japanese photography or discussing an exciting new project with an artist in their studio in Zürich. I feel privileged to work with such an inspiring range of experts, artists and colleagues in the field, and then to pass on my findings and make introductions to clients. One of my favourite ways to engage with clients is walking them through an art fair and discussing artworks together. We talk about everything from historical and biographical details, to rarity and value, and questions around presentation from preservation to framing and hanging requirements, which helps me uncover what type of photography resonates with them. It’s the ideal mix of theory with the practical.

There’s nothing more rewarding than when a new collector sends me a photo of the first photographic art in their home, or even better if I’m there with them for the install, and can experience the magic of this moment with them.

You help art enthusiasts build and grow photographic collections. Could you share some of the recommendations you give to young collectors starting out?

Over the years, I’ve identified three pivotal steps in the collecting journey: Explore, Reflect & Learn.

‘Explore’ is to look, look, look! Get out and see as much as possible – at galleries, art fairs, photo festivals, museums, artist studios. It’s not only important to sharpen your eye, but also to have the chance to connect with gallerists, artists, curators and industry experts so you can learn from them.

‘Reflect’ is being curious about what kinds of photography speak to you. Are you drawn to early black & white vintage prints or contemporary experimental or conceptual work, or socially engaged photojournalism? Reflect on possible themes or ideas that intrigue you. This often evolves over time, but it’s always interesting to consider what you might want to say, or support, through your collecting. Focus on work that’s meaningful to you. Maybe it makes you contemplate your reality or challenges your perception of something you already have a strong opinion about.

‘Learn’ is about doing your research and going deep. Read as much as you can about the context in which work is made, be it artistic movements and history or each artist’s unique vision and process. Understanding the layers of meaning and what goes into making an individual artwork can really enrich the experience of collecting. Each photographer tends to have its own code or set of rules regarding print specifications and these factors have an impact on value. Pay attention to these, especially for earlier material, look into the

provenance, rarity, print date, and condition. Even with contemporary works, be aware of editioning and buy from a reputable source.

To my mind, it is as much an intellectual as an aesthetic journey. I find photographer Valentina Abenavoli’s statement expresses this perfectly: “My relationship with photography lies between an emotional response when looking at it and an analytical approach while reading it”.

Don’t follow trends, trust your advisors and instincts.

And then dive in, and enjoy!

Collecting art is often associated with big money and investment interest. Do you feel it is the same with collecting photography or do you witness a different audience in this field?

I feel the main thrust of collecting photography is associated with passion and connoisseurship. It has a complex and nuanced nature with regard to particularities around process, technique and print specifications. Historically, photography has often dealt with socially engaged topics, so all in all, I think it attracts an audience with curious minds who seek new perspectives.

Commercially, the photography market is largely removed from high levels of speculation seen in other sectors (painting, sculpture, contemporary), simply because the prices are comparatively low. For example, you can buy a work by a pretty established photographer for $20,000, whereas a comparable painting would be in the six-digits. If an artwork doubles or even triples in value, it is not making a significant impact on the collector’s overall wealth. It’s obviously all relative, but this is definitely a different league when comparing with blue chip contemporary works selling in the millions. Consequently, it is also a very interesting area for new collectors, who can acquire a great variety of engaging work by vetted artists for below $5,000.

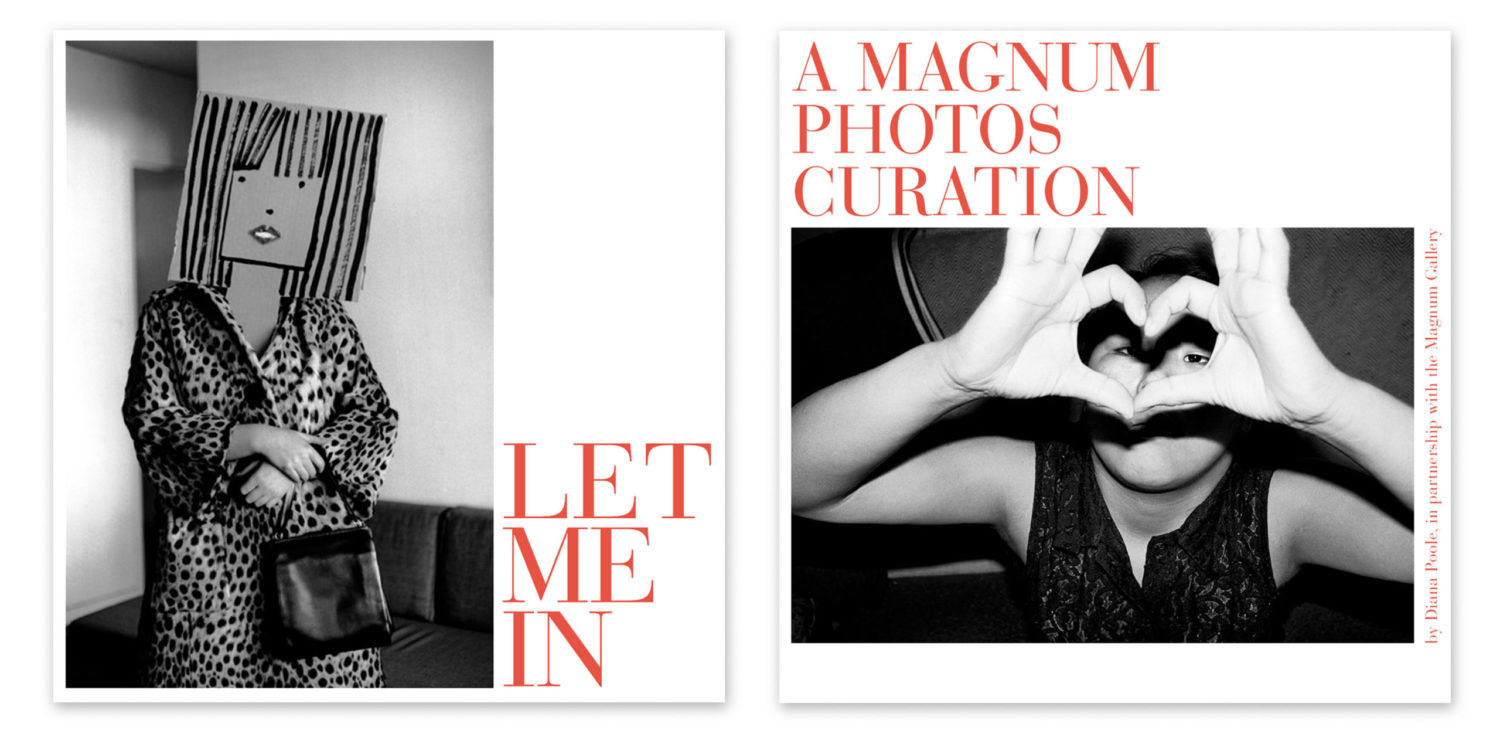

Your recent virtual exhibition – LET ME IN – features 6 Magnum photographers. What inspired you to this project that explores intimacy and the photography’s ambiguous relationship to truth?

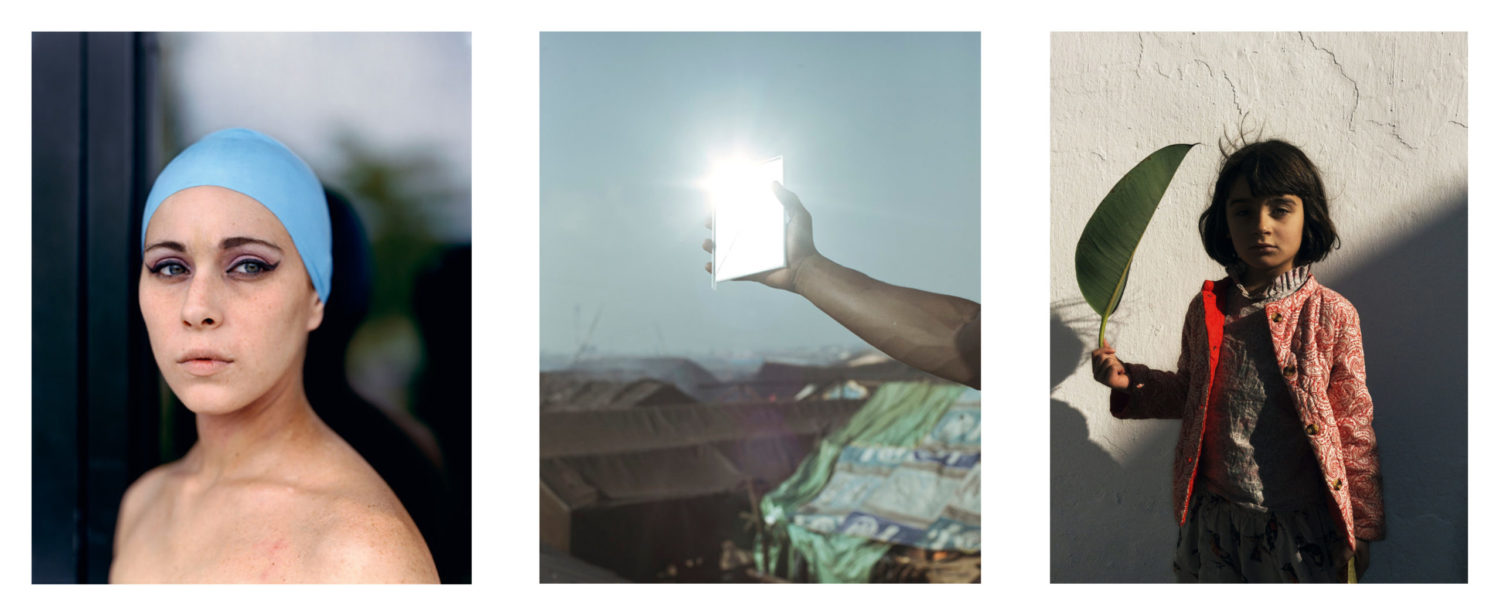

My starting point was to look through hundreds of images from Magnum Photos archives and let those that I instinctively responded to guide me. I was drawn to the closely personal and psychologically charged nature of certain images – especially within a photojournalistic setting. As I looked at the images in my ‘short-list’, the ones that I was especially moved by, I realised were all seemingly intimate portraits that actually had a strong distancing effect on the viewer.

Christopher Anderson’s personal and beautiful photographs of his daughter ‘Pia’, or Jacob Aue Sobol’s raw, emotionally charged close-ups, show these photographers’ preoccupation with wanting to “expose layers in people that are not immediately visible” (Aue Sobol). Despite the ‘closeness’ they privilege us with, I felt there was always so much still left undisclosed. Through this came an exploration into how much we could ever enter into the inner worlds of others, even those closest to us, and the veils we all wear. This is so poignantly expressed in Inge Morath and Saul Steinberg’s ‘Mask Series’ – by concealing their subjects’ faces, they reveal a far eerier and suggestively sinister side to the 1950s American Dream.

From this point, I started thinking about how we could ever begin to relate to the experiences of others – whether living in a different country, or experiencing the horrors of a war zone or natural disaster – and the photographer’s role in taking us there. I was fascinated by how Cristina de Middel embraces fantasy to build a more nuanced portrayal of reality in her series ‘This is What Hatred Did’ – and whether the veil of mysticism in her photographs allows us to somehow get closer to the truth. Or how in Alec Soth’s large-format colour photographs of people and scenes from America’s disconnected communities, he manages to drill down to the essence of his subjects. I included his ‘Niagara’ images, which made me feel palpably the heavy layers and darkness he found in this place – the ‘romance capital’.

It was interesting to see how these threads emerged, and how the photographers I selected all move beyond traditional documentary photography through subtle narratives, merging fiction and reality with intense emotional and psychological engagement.

1/1 Visuals from online exhibition ‘Let Me In’, in partnership with the Magnum Gallery. Inge Morath, 'Untitled' (from the Saul Steinberg Mask series)’, 1962 © Inge Morath / Magnum Photos & The Saul Steinberg Foundation, NYC; Jacob Aue Sobol, ‘Sabine, Greenland’, 2002 © Jacob Aue Sobol / Magnum Photos.

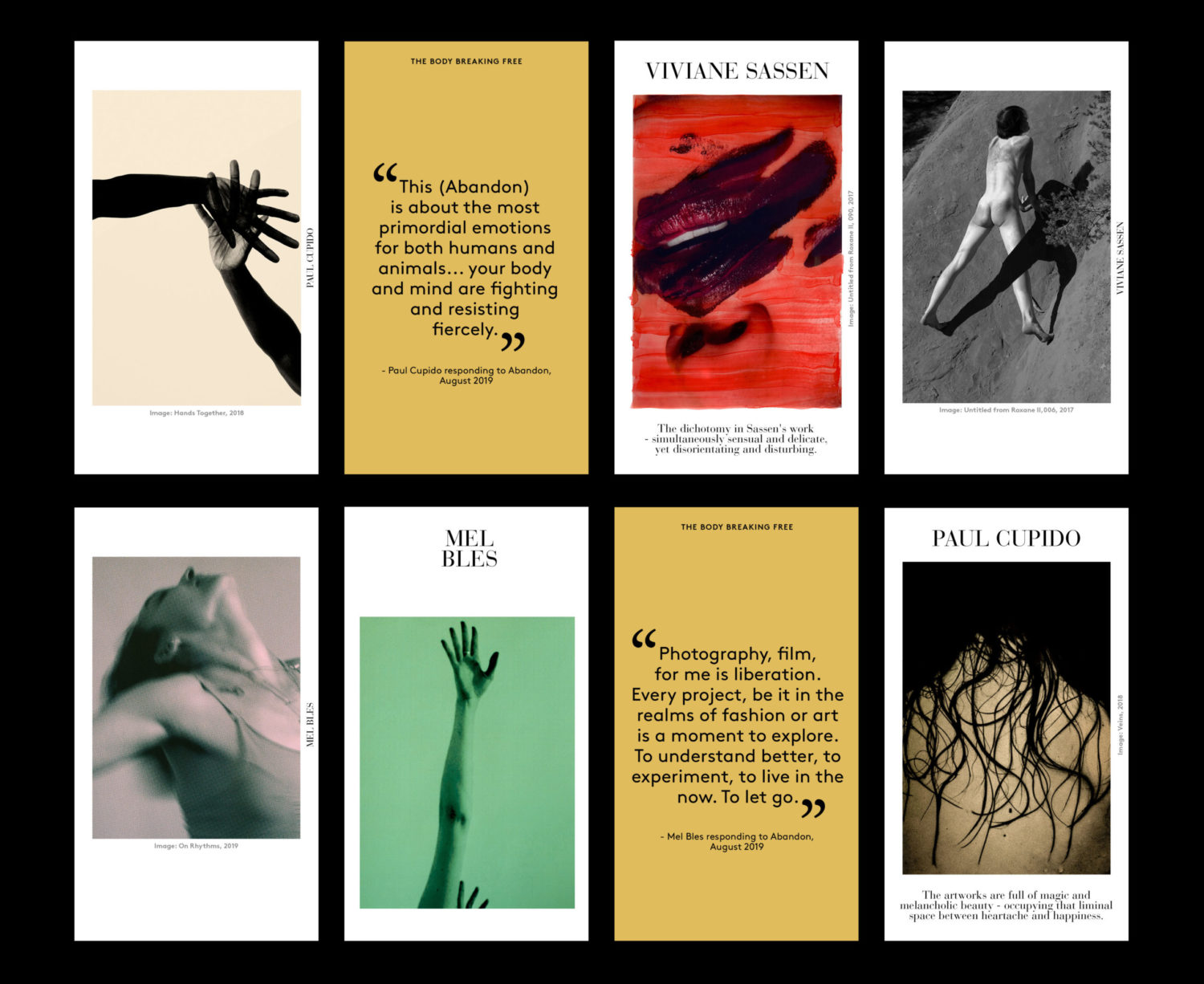

In your series of curated content, you present different photographic artists carefully interlinked by a common theme. Can you tell us more about your online exhibition, ‘the body breaking free’?

The idea for this project started when I visited Peckham 24, London, in 2019 and experienced Mel Bles’ large scale video work ‘On Rhythms’ as part of ‘Dancing in Peckham’ from Webber Gallery and Photoworks. The women moving their bodies so freely with absolute abandon was completely hypnotic and immediately made me feel lighter. I wanted to create an exhibition that would inspire a similar sense of release in others – and of course Mel Bles’ ‘On Rhythms’ was at the core of the presentation.

Since the beginning of photography, the body has been a central subject. Today, we see contemporary artists exploring this form in new ways, relinquishing control and revealing vulnerability, rawness and freedom – also as a means of representing the evolving ideas around identity, particularly gender identity. Alongside Mel Bles, the exhibition featured Paul Cupido and Viviane Sassen. All three artists present approaches that are primal and allow us to reflect on how we move through the world. I felt a natural and very powerful connection between them.

Throughout my online exhibitions, I’m curious about the impact of words and strong graphics, alongside powerful images. How the interplay of photography, typography and narratives can influence our perceptions, experience and understanding of the work. I’m fortunate to work with creative partners such as Torvits + Trench, in Copenhagen and London, who help me bring these ideas together.

Click here to see more of Diana Poole’s work:

website

Instagram

Let Me In: A Magnum Photos curation

the body breaking free