Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

Q&A featuring Sabine Maria Schmidt

Apr 12, 2021 - Simon Lovermann

1. The latest edition of KUNSTFORUM that you edited is titled “Report. Images from Reality“ Can you give us more details on this new issue?

Although almost everyone is currently a photographer or digital image producer, few think about the ever more rapidly distributed media images that increasingly determine our everyday lives and our ideas of truth. They have led us away from (earlier) prudent introspection and into a permanent spectacle of mutually superior propositions.

Although there are countless images, it is becoming increasingly difficult to form a picture of more complex contexts. At the same time, authentic images have become all the more important testimonies with political impact. Unfortunately, perpetrators (murderers and assassins) are increasingly taking advantage of this, such as the gruesome execution videos of the IS or the assassin in Halle, who even wanted to be witnessed with his own live streaming. Journalism has indeed lost a lot of credibility in recent years – due to many fake reports or dubious practices by picture editors. Here, for example, artists and artistic projects such as Forensic Architecture have developed important new methods.

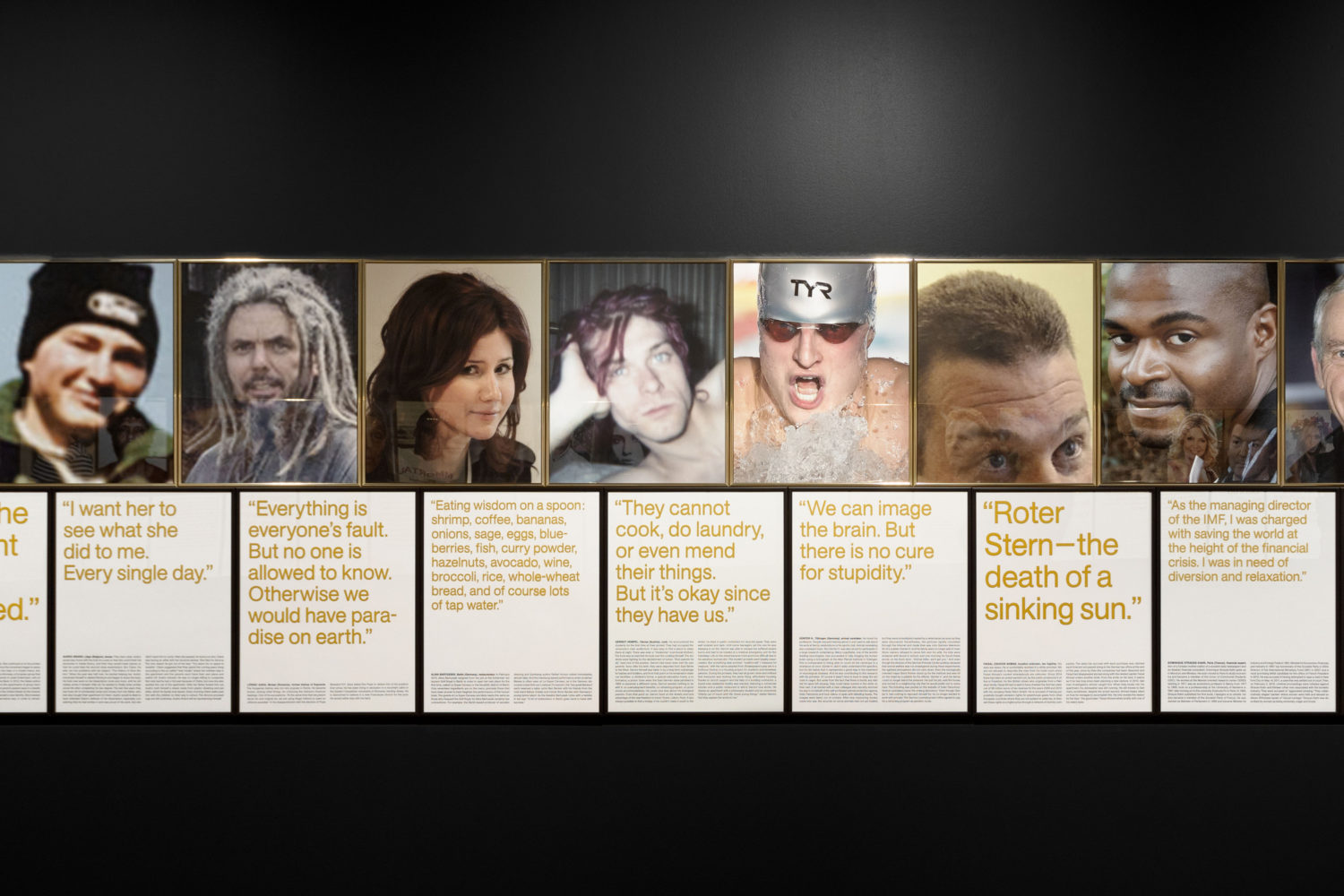

On the other hand, journalistic images have always held great appeal for visual artists; think of the collages of John Heartfield, artistic works from Warhol, Isa Genzken, Thomas Ruff or Alfredo Jaar, Thomas Hirschhorn, Daniele Buetti or Trevor Paglen.

The Kunstforum volume “Report. Images from Reality” thus asks how the apparative-technical image, today the digital image based on lens optics, can continue to be useful as an analytical instrument of truth-seeking – though that may sound a little pathetic. For me, it is unacceptable that a concept of truth that has historically been negotiated over and over again – both scientifically, philosophically and socially – is corrupted by chronic liars like Trump is (to name just one of many other power politicians worldwide) or currently the Corona deniers are. The volume is thus also a statement on the rather dangerous socio-political phenomenon of post-facticity. This gives precedence not to rational reasons and arguments, but to perceived realities and emotions to decide.

Truth is only ever ascertainable and divisible if we know where a fact ends and interpretation begins. This is also important for image analysis. And that has always been the work of artists, to make these often blurred boundaries a subject.

The volume thus consists of several introductory essays by guest authors and myself, presenting numerous artistic strategies that engage with documentary and photojournalistic approaches. Secondly, two themes are explored: the importance of photographic and photojournalistic archives for artists and the old interplay of “observing and being observed” or “supervising the supervisors”, a relationship that is both aesthetic, erotic and political. Since the 1990s, many historical press archives have been digitised and the struggle for images or the power over images has also become an economic one, as the monopolies of a few picture agencies such as Getty Images, founded in 1995, illustrate. The stories of the picture agencies have all yet to be written.

2. Could you outline how you’ve approached the artistic and documentary photograph in the issue, how and where you’ve drawn the line between reality and fiction?

We all know that images are made, that every image is constructed. “No one can write fast enough to tell a real story,” wrote Ryan Milan (“The Lion Sleeps Tonight”), in other words, no one can photograph fast enough to capture a historically complex event. Since the advent of digital photography, media and representation critique has been part of the tasks of photography, video, net and media art, and countless works of art have taught us an incredible amount. I myself have curated various exhibitions on the thematic field around fact/fiction, first in 2000 at the Edith Russ House for Media Art in Oldenburg; later with a large retrospective of Aernout Mik at the Museum Folkwang in 2011/12 or a solo exhibition with Korpys/Löffler in 2017/2018 at the Kunsthalle Tübingen; to mention just a few examples.

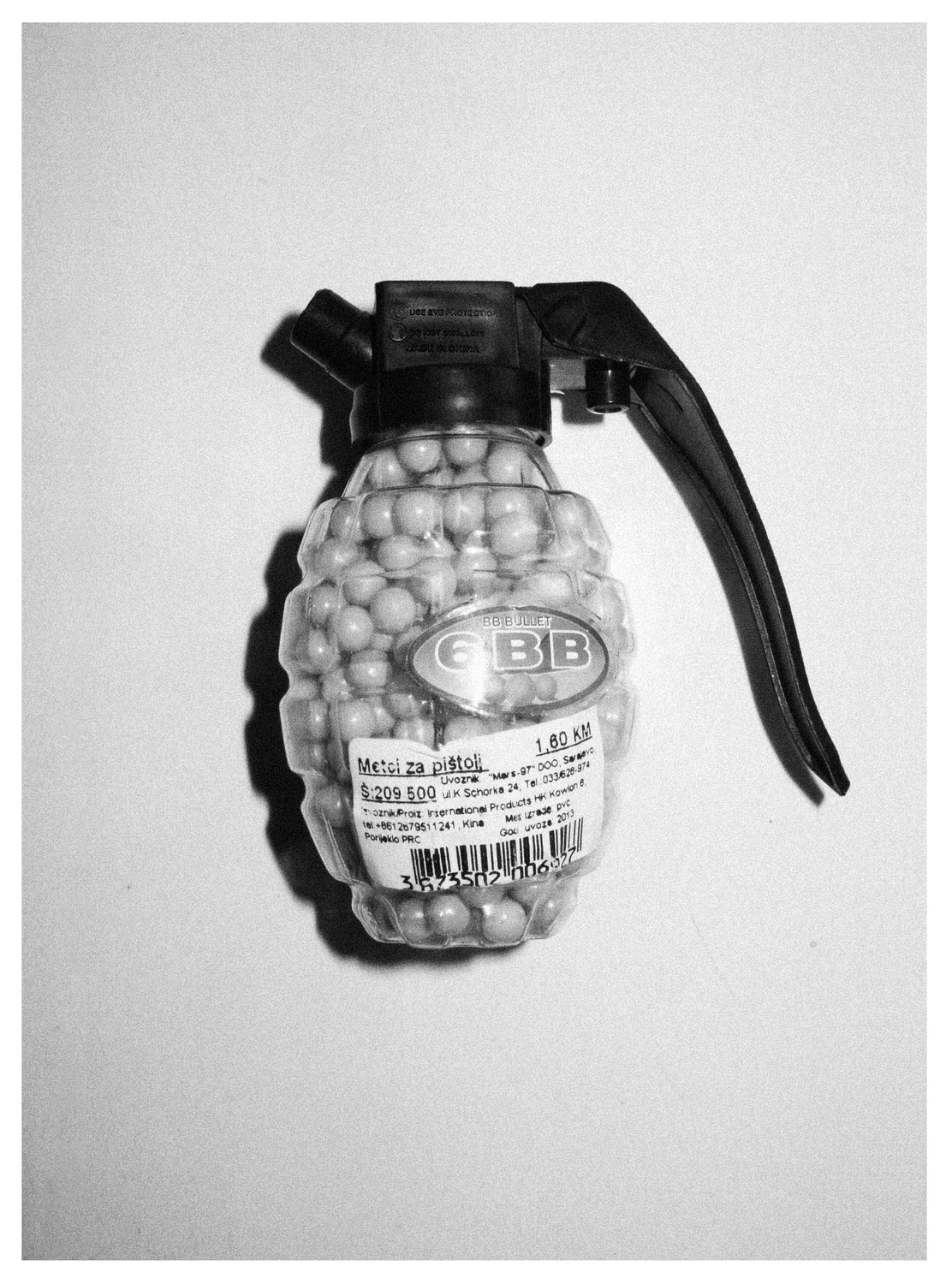

The classical terms of photographic theory have also had their day, since the forms of documentary have diversified very widely and a theoretically drawn dividing line between genres such as journalistic, documentary or artistic photography no longer seems productive. On the other hand, it is nevertheless important to continue thinking about this. For we need photojournalism and a critical corrective in a battle for images that mostly flanks warlike and propagandistic interests (information warfare). Photographic images are incredibly powerful, but in their mostly digital presence they are also enormously fragile and at the same time quickly made invisible (unpublished, deleted or censored). The fundamental problem of photography is that its underlying medium disappears behind what is shown (e.g. film, exposure on paper).

Where do pictures come from? What purposes do they serve? What do I really see? In what context do the images belong?

For journalism, this means: new sets of rules are needed to ensure credibility and strengthen witnessing. There are many proposals that can still prevail. The New York Times started the News Provenance Project, Fred Ritchie initiated „The Four Corner Project“ – both add contextual information to the images. But the readers are also in demand. It is no longer only those who produce the images who are responsible for their effectiveness, but also those who quote and share them. In fact, everything that moves people today takes place primarily in the engagement with images. It is therefore all the more important that we are not only guided by the excitement potential of images or through images, but that we also know their “protocols”.

3. Can you tell us a bit about the authors you invited to contribute to this issue and the selection process?

Of the authors, I invited younger colleagues such as Christin Müller (Leipzig) or Felix Koltermann (Berlin / Hanover), who had caught my attention through their text contributions or who were recommended to me during my research. Jolanda Wessel, for example, is doing her doctorate on Hito Steyerl, who shaped the term “documentarisms”. I asked Wessel for an annotated text collage on Steyerl’s theoretical work. Jan Wenzel from Spector Books had curated the f/stop festival in Leipzig together with Anne König in 2016 and 2018. I asked him to look again at an image, which filled all the headlines in 2015. The one of the drowned little boy Alan Kurdi, which he puts in context with Bertolt Brecht’s “Kriegsfibel” (War Primer). For the curator interviews, I deliberately referred to the German scene and approached some important curators of museum collections; unfortunately, travelling to interview partners and festivals has become so difficult since the pandemic. I asked them about their approaches to the “documentary”.

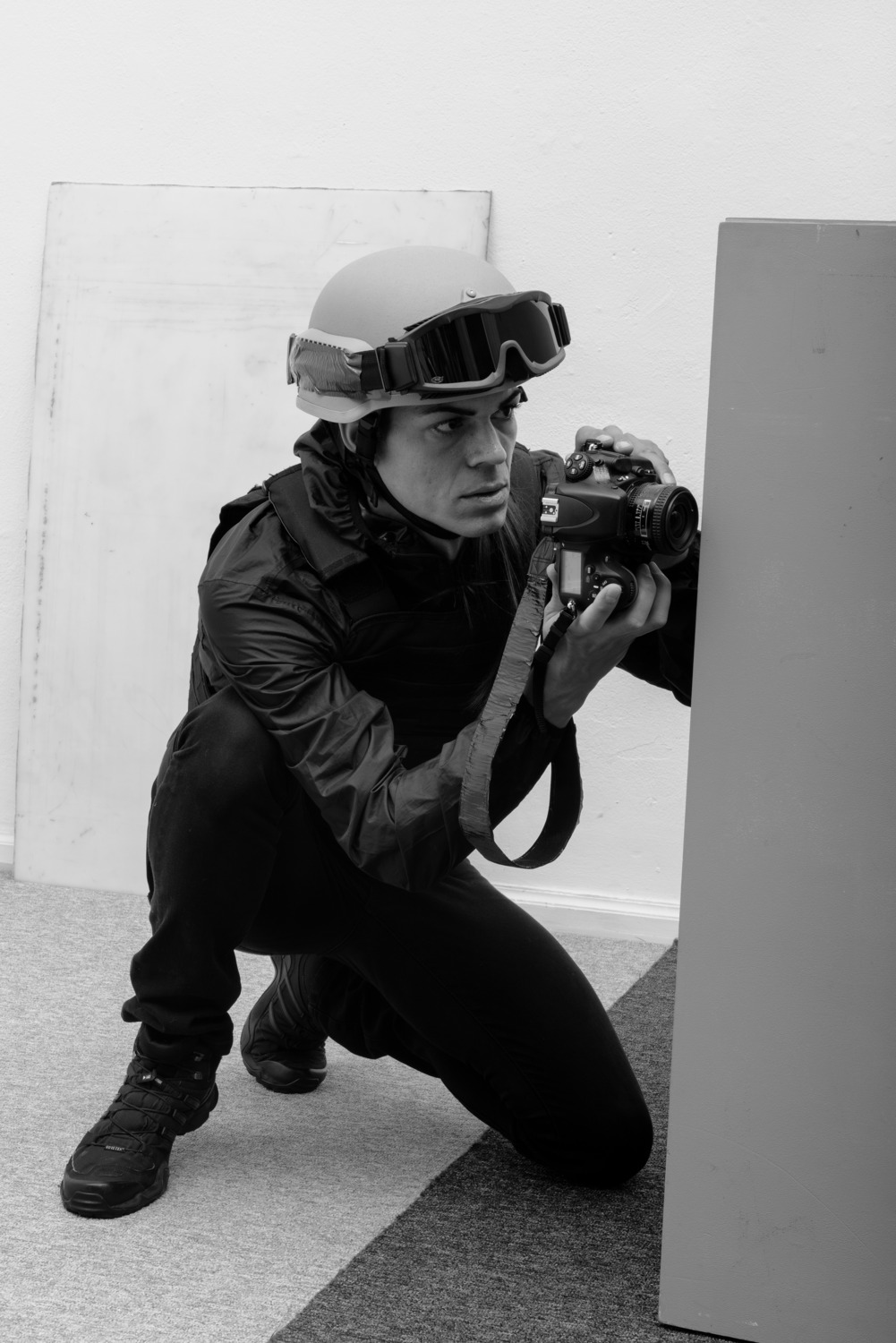

In the selection of the artists, I wanted to present positions that explicitly and seriously deal with the questions of journalistic documentarism and artistic documentarism over a longer period of time and combine both forms with each other or aesthetically examine them in their work. Artists such as Korpys/Löffler photograph and film state visits by the American president as well as street demonstrations. They portray political and economic architecture, such as the ECB Bank in Frankfurt, in order to research the structures behind the images and the edges of what has been seen so far. In doing so, they always reflect on the photographic image.

Holger Wüst usually uses existing images to bring highly complex social and economic contexts into the picture, such as the history of left-wing ideology-critical trench warfare in Frankfurt (since Adorno), university history, Marxism and anti-Semitism. The French photographer Bruno Serralongue has been working in Calais for over 5 years to get a picture of the refugee crisis. The artist duo Stuke/Sieber are developing their own form of travel reportage in which historical and geographical routes are reconstructed photographically.

4. We see the internet as an ever growing archive of images. Can you point out specific artists whom you think have a particularly interesting approach towards working with(in) this archive?

Most of the images on the web today are no longer made by people, but by machines. The concept of an archive, which is subject to keywording and classification criteria, is therefore not really accurate. I find it particularly interesting that artists and journalists are dealing with “databases” produced by algorithms or automatically controlled systems such as surveillance cameras. This was and is the subject of many artists like Bruce Nauman, Julia Scher, Michael Klier or Trevor Paglen and James Bridle. Denis Beaubois had already staged a kind of play with stage directions for surveillance cameras in 1997. I can still remember his Media Art Award at the ZKM in 2001. The photographer Andrew Hammerand, one of the few photographers pictured whom I have not met in person (which is important for my work), hacked a video camera in a small US state and took amazing screenshots of its recordings.

The artist duo Achim Mohné/Uta Kopp, on the other hand, produce images on the roofs of houses, which they feed into the databases of satellite systems and which are (supposed to be) retrieved later in Google searches. I don’t think we can even imagine the actual scope of data archives that are currently being collected about us and the world. Armin Linke and Estelle Blaschke have brought the term “image capital” into play, which I find very inspiring, since images and data have also become currencies. Trevor Paglen is already a classicist in this field; in his latest work, “Bloom”, he sends faces and photos of flowers through image processing software that reinterprets and produces them based on other flower photos on the web. “Data harvesting” is what he calls the results of the algorithms.

5. We would like to invite you to share 4-5 projects, presented in your latest edition, that also engage in working with crowd-sourced archives as a main element in how their makers see their own contribution in photography

As an archive, the internet naturally functions quite differently from classical archives or working with analogue archives, which are unfortunately increasingly being dissolved. Analogue picture archives in particular are a great attraction for artists. Philipp Goldbach, for example, works with the slide archives of art historical institutes, Bogomir Ecker uses journalistic photographs he has collected for sculptural surveys. Jochen Schmid, who collected found and discarded pictures “on the street” as early as 1982, founded an archive for “rag photography” many years ago and has given a multi-faceted demonstration of the artistic use of everyday and amateur photography. For him, every photo is a document. Michael Wolf, who recently passed away, often arrived at similar results with internet finds.

Peter Piller’s humorous thematically and formally structured combinations contrast with the all-over approach of Erik Kessels, who simply printed out a day’s worth of images from the internet. According to Foucault, history transforms monuments into documents and the archaeological method transforms documents into monuments. This becomes physically tangible in the confrontation of these artistic positions.

6. We’re interested in hearing more about why you chose to engage with the image in its current documentary form. Do you think it’s currently possible to really engage with the digital age and the amounts of images taken? How do you think this has changed the ways in which documentary photographs are viewed and exchanged?

There is a very conscious use of documentary strategies, also by a younger generation of photographers. And they ask how the digital media are changing the visual language. They counter the overheated image culture with a kind of “slow media” attitude. They often step back as authors, or work under collective authorship. Others cooperate with scientific institutes that have developed new imaging techniques. Instead of the legendary “decisive moment” of a photograph, they link different time levels in their reportages. Artists like Sven Johne, Eiko Grimberg or Adrian Sauer develop very sophisticated text-image constellations for their long-term research. Viktoria Binschtok sends her photographs online and leaves them to be analysed by algorithms.

Another aspect would be important to me at this point. What happens to the pictures that are taken of us and that we take of ourselves?

In the past, there were two forms of archives for this purpose: those of the “watchdogs” such as detectives, police and secret services, or the private photo album. This relationship between secret, private and/or public has completely dissolved. What will that mean for us in the future?

With the fall of communism and the dissolution of the former Eastern bloc, many secret service archives have become accessible; in Germany, the Stasi files. In recent years, there have been important exhibitions and haunting artistic works that illuminate the bewilderment with which “the lives of others” were documented. I often ask myself whether we will also get to see such data archives of ourselves again, which have strongly influenced the way we plan our lives without us knowing about it.

7. Your latest edition discusses current models of reception and distribution of photography who contribute towards the reading of images. Which ones do you think are particularly interesting?

There are so many fantastic images that are exciting, beautiful, stubborn and quirky or simply touching. I am quite interested in images that show me that what I see cannot be true.

Thank you for taking the time to answer these questions, Sabine Maria Schmidt!

More information about Kunstforum, issue 273: Report. Images from Reality