Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

Para-Phrase: Anne Morgenstern & Jonas Lüscher

Mar 19, 2018 - Gita Cooper-van Ingen

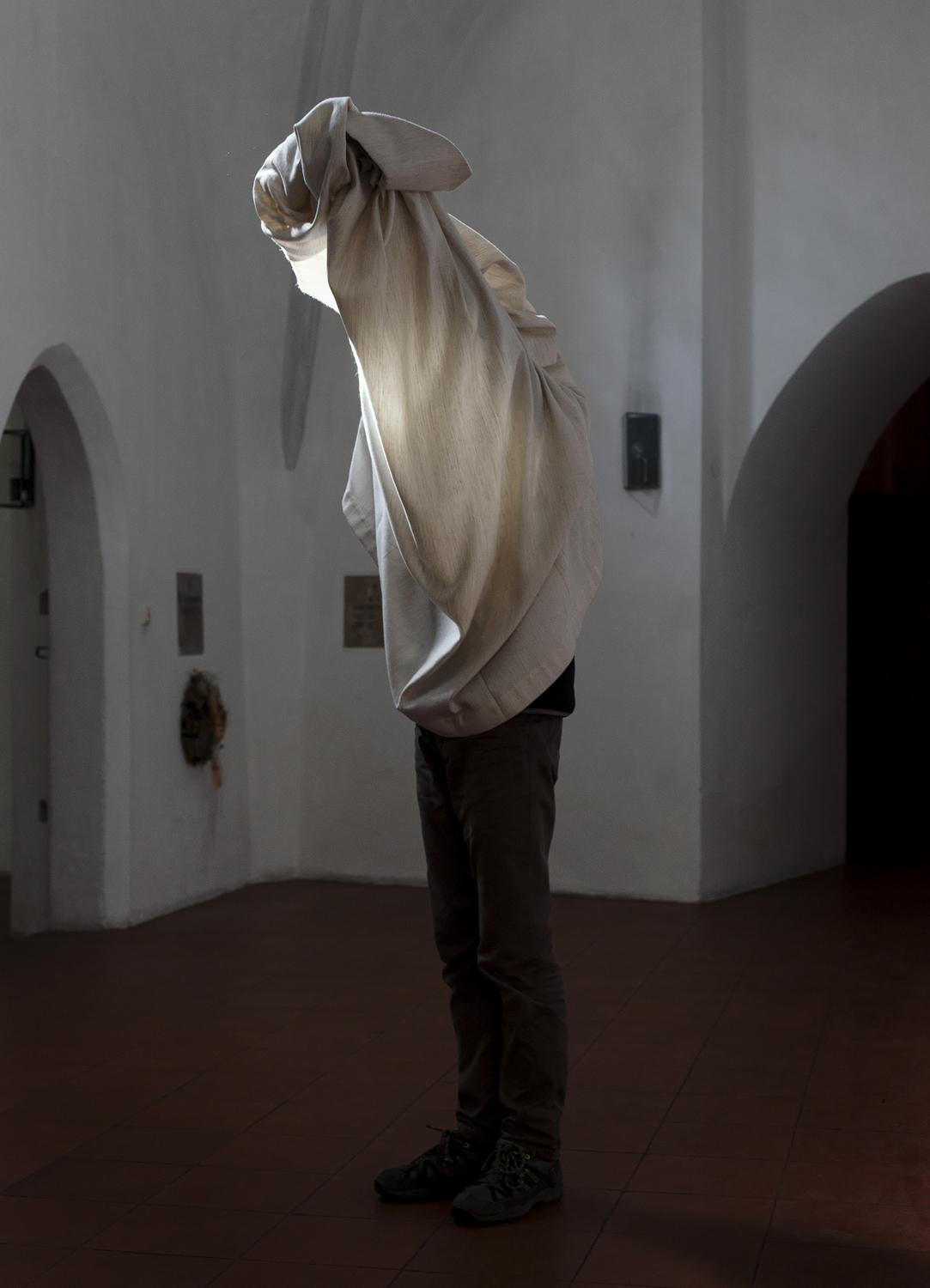

What happens when twilight makes the familiar become foreign, when things elude visibility and lose their clarity?

In her recently published book “Reinheit”, Anne Morgenstern investigates the mysterious notions of rural community oscillating between traditions, customs and modern life. These interests lead Morgenstern to closely investigate the Freistaat ( – Free State) of Bavaria. In this laboratory of contradictions, she makes it possible to see how notions of “homeland” and “culture” are asserted – but also how they are dismantled and reformulated. She seeks out fragile moments, in which the desire for authenticity and purity is thwarted by the ordinariness of everyday life. Her observations revolve around people and their rituals, via which the ostensibly familiar is given validity in the midst of a vague present-day world.

The book is published by Fountain Books Berlin.

Text written by Jonas Lüscher in German, translated by Tess Lewis.

Saying holy names, he doesn’t understand why it’s bad, why it’s something they have to confess. Being rough with the cattle and the wife, that yes, that he knows from home. Six rosaries had been his going rate in Pointe-Noire – two for the cattle and four for the wife, he’d always stressed in the hope that someday they’d change the order of their esteem. He knows, of course, that first you have to be able to afford esteem.

Six rosaries, my son, he said and saw, through the carved latticework, how Bachmeier’s face fell and the pinkish hide under his chin started trembling as the latter repeated the draconian penance in disbelief and asked twice if he’d understood Father correctly or maybe Father got himself mixed up with the foreign numbers? Just to be sure, Bachmeier slowly counted to six, as if for a child, and he struggled to suppress his dialect for the priest. Behind the grille, Bachmeier extended a finger from his fist for each number. Yes, the priest confirmed, six; one, two, three, four, five, six, even if what Bachmeier was showing him there could only ever amount to five, by any stretch. Then he gave a laugh, rather loud and hoarse. Bachmeier had stared at his hand, at the scarred stumps of his middle and ring fingers thanks to an accident with the tailboard of a trailer. It took him a moment to realize the priest had made a joke. Bachmeier obligingly laughed along. That was new for Bachmeier, too, laughing in the confessional. Maybe his wife was right when she’d said that Africans, as a rule, were a fun-loving lot who liked to laugh; a remark that had earned her a strict rebuke from their daughter.

Since then, he had reduced his standard penance to five Our Fathers and five Hail Marys. He’d quickly realized that he’d have to adapt. And to learn how much everything cost. Knowing the price of things soon seemed what was most important.

He took the dog for walks in the industrial park.

Elias would rather have taken the dog with him on vacation, but after a long deliberation, he had decided to go on a group tour of the Galapagos and witness the wonder of creation through evolution with his own eyes. The dog, of course, had to stay home.

Initially, he had taken the dog on the route Elias had shown him. Behind the rectory, along the cemetery wall, through the fields, over the small bridge, then past the meadows and up to the edge of the forest. That’s where they ran into the women. The ones with the big houses and two-car garages. They were there in every kind of weather. Neither rain nor the heat of summer seemed to make any difference to them. When it rained, they changed their sneakers for rubber boots and wore waterproof jackets; and when the sun beat down in August and threw jagged shadows across the field paths, they put on their baseball caps, pulled their blond hair through the hole at the back and let their ponytails whip back and forth. Some walked in small groups, chattering with each other and scolding their dogs in loud voices. Others walked alone at a brisk pace as if they still had errands to finish. The dog-women, as Elias called them, did not come to church. Even though it would do them good. There’s something adrift about them. Nevertheless, they’re part of his flock. He just brings the Church up to them there at the edge of the forest. You have to approach these women, Elias told him. First they talk about their dogs, then about their children, then about their husbands and at some point, if you listen well, they’ll talk about themselves.

He didn’t have to approach them at all. They came to him on their own, complimented him on his German, some of them excused themselves, laughing sheepishly, for not coming to church, and asked how he was doing so far from home. Was he homesick? They also wanted to know where exactly Pointe-Noire was and how should they picture it. A few talked to him about Africa, about trips they’d taken to Namibia and Malindi or about other Africans they’d met over the course of their lives. Then they talked about their dogs, then about their children, then about their husbands and soon about themselves. He found the conversations exhausting. There was something adrift about them, Elias had said. Adrift. He wasn’t familiar with the word, but now he thought he knew exactly what it meant.

He couldn’t help them and started avoiding the edge of the forest, taking the dog to the industrial park instead. With an uneasy conscience. But Elias would take over again in a few weeks and until then they’d surely do just fine – they didn’t appear to be in acute distress, rather they seem afflicted by a kind of discontent he believes he can detect just under their skin. All their talk of dogs, children, husbands and themselves seems intended to plow under any and all roots, so that what was sprouting in broad daylight would disappear, return where it came from. These women’s lives are too alien for him to feel it appropriate to encourage them in one direction or the other. He has absolutely no way of gauging what kind of objections might arise in this community, whose spiritual salvation had been entrusted to him, albeit temporarily. And so, he decides to avoid the edge of the forest and walks the dog in the industrial park.

After work, a group of young men gather in front of a metalworking company. They’re drinking beer and sweating over a giant cross they want to erect on a nearby peak this summer. He had already been asked, with concern, if he’d ever been on a mountain peak before, since it will be his duty to accompany the young men to the mountaintop and bless the raised cross.

Here, watching the young men at work, he realizes what the issue is with saying holy names and why they need to confess it. They swear when something doesn’t work or when one of the thick iron rods won’t submit to their will as they hammer away at it, taking God’s name and those of the sacraments in vain despite his presence.

He recognizes most of their faces from church. The young men come regularly, not every Sunday, but regularly enough. They bring their wives and small children they’re only too happy to take outside when the crying disrupts the mass. They don’t come to confession. Only a few elderly people show up for confession – Elias had prepared him for that. In a few years we’ll be able to use this as a broom closet, he’d said when they were standing in front of the confessional one day.

The vestments hang from his shoulders as from a coat hanger and while the fine damask stretched over Elias’ belly, the gold embroidery disappears in the folds. He’s almost wasting away the women told him, laughing. Like a bag of antlers. Did he get it? Bag, yes … he got that. But antlers … They raised their hands to their foreheads and lifted them in a curved motion as if they were imitating the Horned One’s headgear. And if you shake the bag, you can hear rattling, they said. They laughed and he joined in, showing his crooked teeth. But that’s about to change, they promised in a tone that sounded threatening to him, he’ll see soon enough.

It’s no empty promise; they keep their word with the full fury of their united baking skills. Baked goods appear at every opportunity. Every village fête, every home visit, after mass and choir practice, during Sunday school and the parish council meeting, and before the Caritas donation assembly. And always too much. Much too much. Always such excess that he can’t decline when they want to send him home with a plate full of leftovers.

And when he returns the plate a few days later, washed cleaned, they often refuse to take it but send back the porcelain dish heavily laden with rich pastries and with it, the hapless, helpless priest, that is, when they don’t seize the opportunity to pull him into the house by the elbow and press him into the soft upholstery to fatten him up on the spot.

He has the feeling he’s always trying to open the parish house door with one hand while balancing a brimming plate in the other. And occasionally he also has to step over a full platter, which one of the women, taking advantage of his absence, has left on his doorstep.

The dog is no help. He won’t eat any cake. The damn cakes. The cakes that pile up in his refrigerator. Which have become his main source of nourishment because he can’t bring himself to throw them away. He has developed a system in which he shoves the old cakes from the back to the front and from the top shelf to the bottom, so that the oldest pieces always end up in the front right vegetable drawer.

At a certain point he loses control of the baked goods and early in the morning a fuzzy green layer creeps over the cheesecake in the vegetable drawer. Swearing, he scrapes the fur off with a knife and sits down to breakfast at the kitchen table with four slices instead of his usual penance of three. In Elias’ silverware drawer, he found a tiny spoon with an enamel portrait of the deceased Polish pontiff on the handle. The spoon’s handle tapers to a pointed miter. It works better with this spoon. Very slowly, spoonful by spoonful, he eats the cake, but he has the feeling that Peter’s successor is at his side, lending him support in the difficult trial the women have imposed on him.

In front of the metalworking company, the cross lies on two sawhorses in the sun and reminds him of the Golden Gate Bridge, which he knows only from pictures. The same orange paint. Rust-proofing.

The dog runs ahead and he follows rather sluggishly. One of the dog-women is coming towards him, one of those whose name he doesn’t know because she doesn’t come to mass or bake for him. They pass and he greets her. She doesn’t greet him. He thinks of Elias and the word he used: adrift. Why isn’t she up at the forest edge with the others?

On the way back he sees her standing next to the freshly painted cross. With a fingernail, she presses tiny half-moons into the still soft paint. The dogs bark at each other, she turns and looks through him with reddened eyes as if he were as strange to her as she is to herself.

He walks quickly past.

At home he places the garbage bin in front of the open refrigerator and tips the cakes into the black bag. One plate after another. Until the refrigerator is empty.

He lies awake at night. And because he doesn’t want to think about the dog-woman, he goes over in his mind everything he has to do the next day. Mrs. Lewandowski – no relation to the football player, unfortunately, she explained – will come, as she does every Wednesday to do his laundry, clean Elias’ apartment, dust the furniture and take out the garbage …

He gets up. He goes into the kitchen in his pajamas, pulls out the garbage bin from under the sink and carries it to the toilet. On his knees and with his bare hands, he scoops the cakes out of the bin and shovels them into the toilet bowl. After every fifth handful, he flushes and watches the paste disappear in a swirl, gobs of cream, chocolate sprinkles, strawberries and raspberries, halved plums and finally the rhubarb fibers that swim on the surface for a long time.

Para-phrase is an online project that commissions pairings of images and text, where a photographer is invited to submit images and a writer is invited to respond to the selection. It offers a platform for exchanges and responses between artists, writers, and curators whose work produces and promotes the discipline of lens-based media. Para-phrase draws on the multiplicity of artistic processes and aims to encourage their exchange. It supports a wide range of voices from an expanding network of practitioners open to collaboration and exchange and shows that the outcome reflects the many, varied approaches of how to interpret both image and text. Both the acts of writing and photographing attempt to interpret the world, to decipher the symbols, figures, data, complexities of our respective realities.