Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

Radicalia – Piero Martinello – Longo

Mar 03, 2017 - Piero Martinello

RADICALIA – Piero Martinello

March 1, 2017 – Natasha Christia – Curator

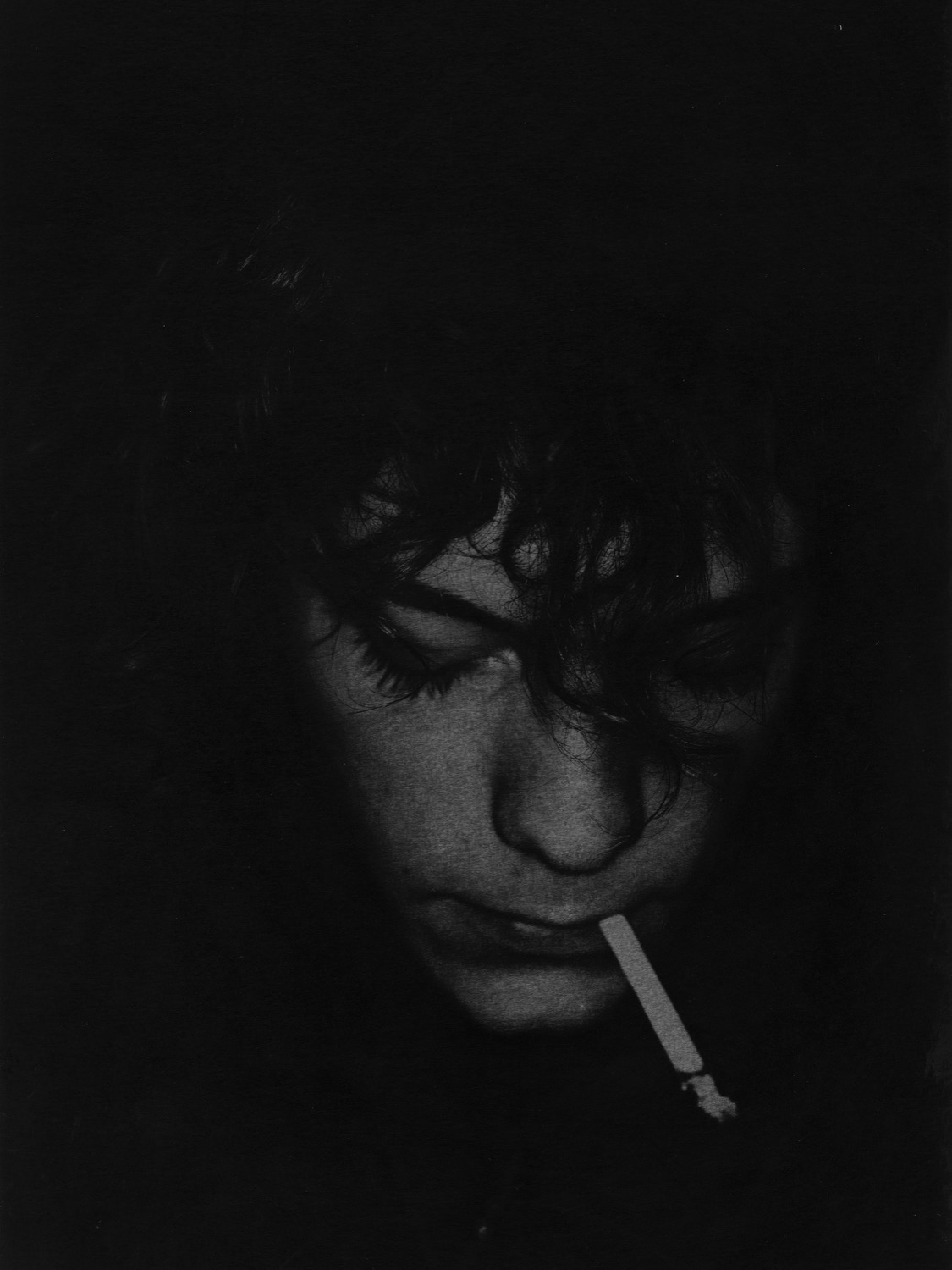

Piero Martinello has travelled around Italy in search of women and men who, each in their own way and for different reasons, have embraced unconventional life paths. Town fools, ravers, criminals, saints, devouts and cloistered nuns… They are outcasts, outlaws or simply outsiders occupying the fringes of society. All of them come to life in Radicalia, a concept album arranged as a wall mosaic of household genealogies and a five-chapter book. Here the photographic medium appears either in its pure form or in vernacular photography items (passports, holy pictures, and mug shots, among others).

An anthropological assemblage of characters and traits, Radicalia echoes August Sander’s “The Last People” portfolio from People of the Twentieth Century. Like its protagonists, it is eccentric and uncompromising at heart. Above all, it transmits a raw authenticity and a familiarity that bespeaks our collective age-old roots. Its typology is put at work via an Italianfolklore parade of individuals and anecdotes on the tainted relation between doctrinaire thought, deviation and stigma.

There is something ecstatic in the expression of these heretics —a driving force of genuine devotion, passion and eversion emanating from another world. Their portraits turn into relics of both a sacred and profane past on the verge of extinction.

Amidst the massified and homogenized subjectivities of our times, little is left to today’s reactionaries. Perhaps just to remain confined in the illegible realm of their spirit. For, when it comes to being photographed, there is no way back. Photography by definition unveils the ‘photogenic’ face —a face with no other option than being naturalized within a determined system of stereotypical representations. As soon as this happens, the fierce beauty of Martinello’s subjects is canonised as the by-product of an avid visual mythology destined to eradicate and perpetuate the rule patterns of the collective consciousness. This is the bitter oxymoron that Radicalia performs: the literal extinction of Sander’s ‘last people’.

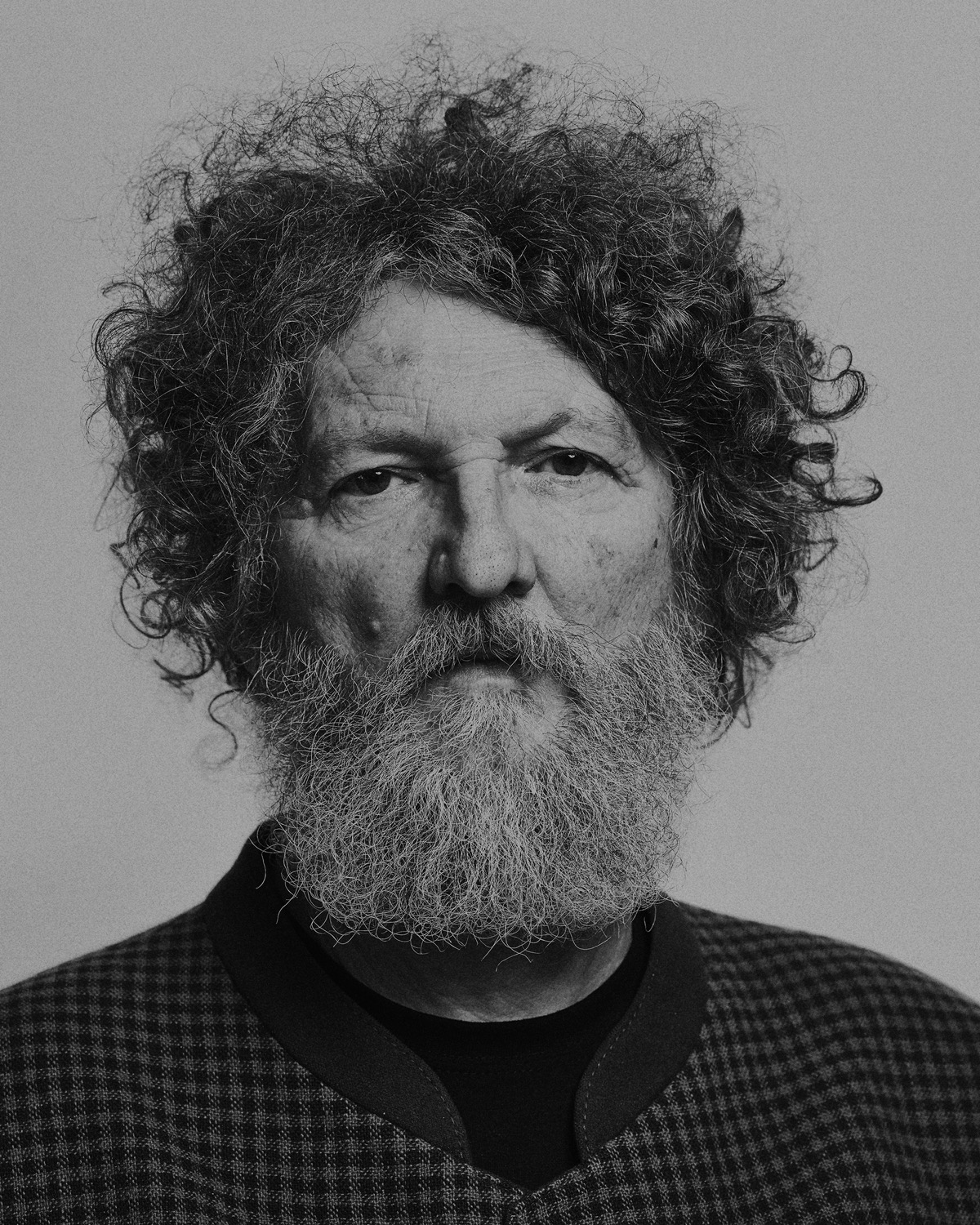

1st CHAPTER: RADICAL AS DEVIATION

Up until a few decades ago, every Italian provincial town had its fool, just as it had its chemist and its local Carabiniere. So-called “town fools” were men and women with different stories and problems. Some had been locked up in asylums; others never left their community, of which they were very much a part and which supported them. Others still were thought of as ´odd´, having left their hometowns in search of fortune abroad. Village fools are still around, though their role in society is less acknowledged today. They often dress in eccentric, eye-catching outfits, and lay claim to an identity that defies the standards of efficiency, productivity, costs and earnings that define other people and rule the world around them.

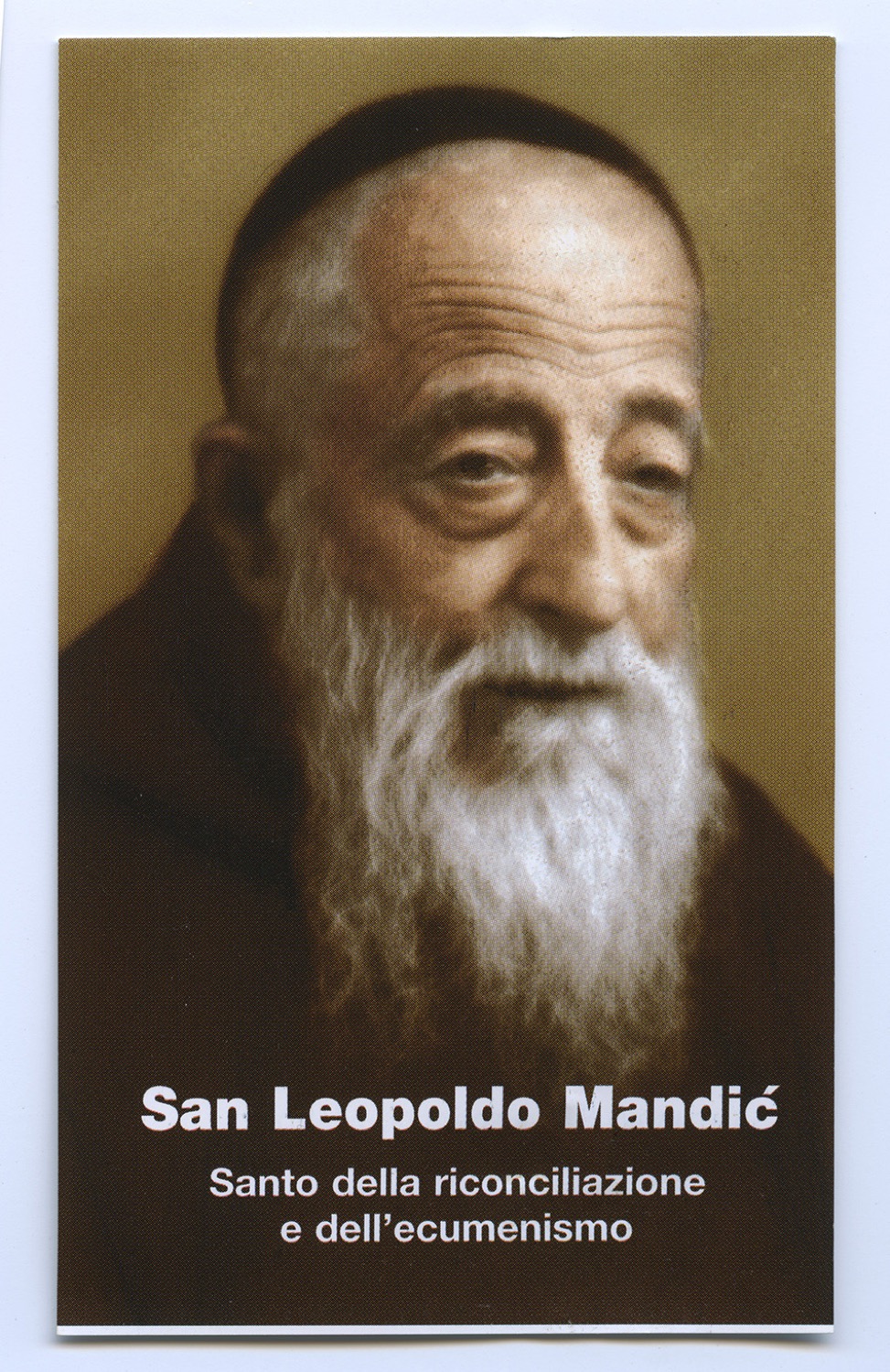

2nd CHAPTER: RADICAL AS DEVOTION

The most complete text on Saints and Blesseds venerated by the Catholic Church, the Martyrologium Romanum, lists about ten thousand saints, whilst seventeen-volume encyclopedia Bibliotheca Sanctorum includes over twenty thousand entries. In the book of the Apocalypse, Saint John altogether dispenses with the feat of counting them.

To aspire to sanctity, men and women must give proof of their faith through martyrdom, modelling their lives on that of Christ to the point where after death the Pope certifies their presence in Paradise before God. But besides official liturgy, the canonical procedure for sanctification has deep ties to popular religion: it is necessary that a group of devouts gather evidence of the exceptional life conduct of a servant of God for their death, the people will continue to venerate them, recount their story, dedicate ex votos, songs and poems to them; they will name their newborns after them, and untertake pilgrimages and processions in their honour.

Every Italian city has its own saint, a sort of local embodiment of the supernatural. Worship may take on radical and obsessive forms, in which devouts embrace life choices comparable to those of the saints they venerate to the point where the lives of the saints end up being inseparable from those of the devouts who tell them.

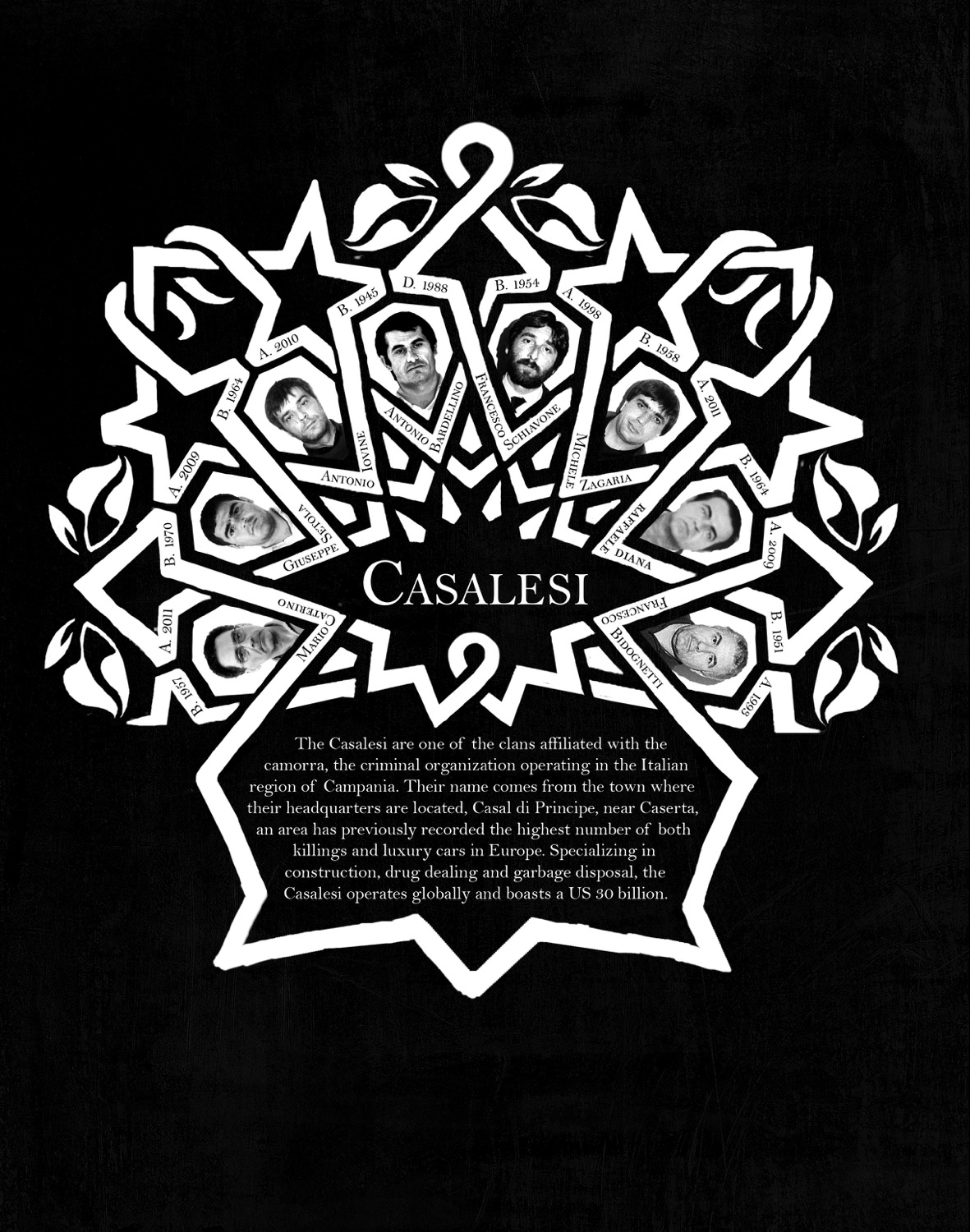

3rd CHAPTER: RADICAL AS EVERSION

Italian Mafias are holding companies that do business by means of the indiscriminate use of violence. Italian journalist Roberto Saviano claims the Mafia killed around ten thousand people over the past thirty years. At present, it has an army of twenty-five thousand affiliates, two-hundred thousand direct supporters and an estimated turnover of 150 billion Euros per year. Considered together, the Mafias represent the most powerful business in Italy, with tentacles extending to Europe and the rest of the world. Some of the most famous Camorra and `Ndrangheta clans are pictured here in the style of `triumph photography`, a form of photo-collage used in the second half of the nineteenth century to illustrate the organisation of criminal gangs in the Italian South and identify brigands who had been captured or killed.

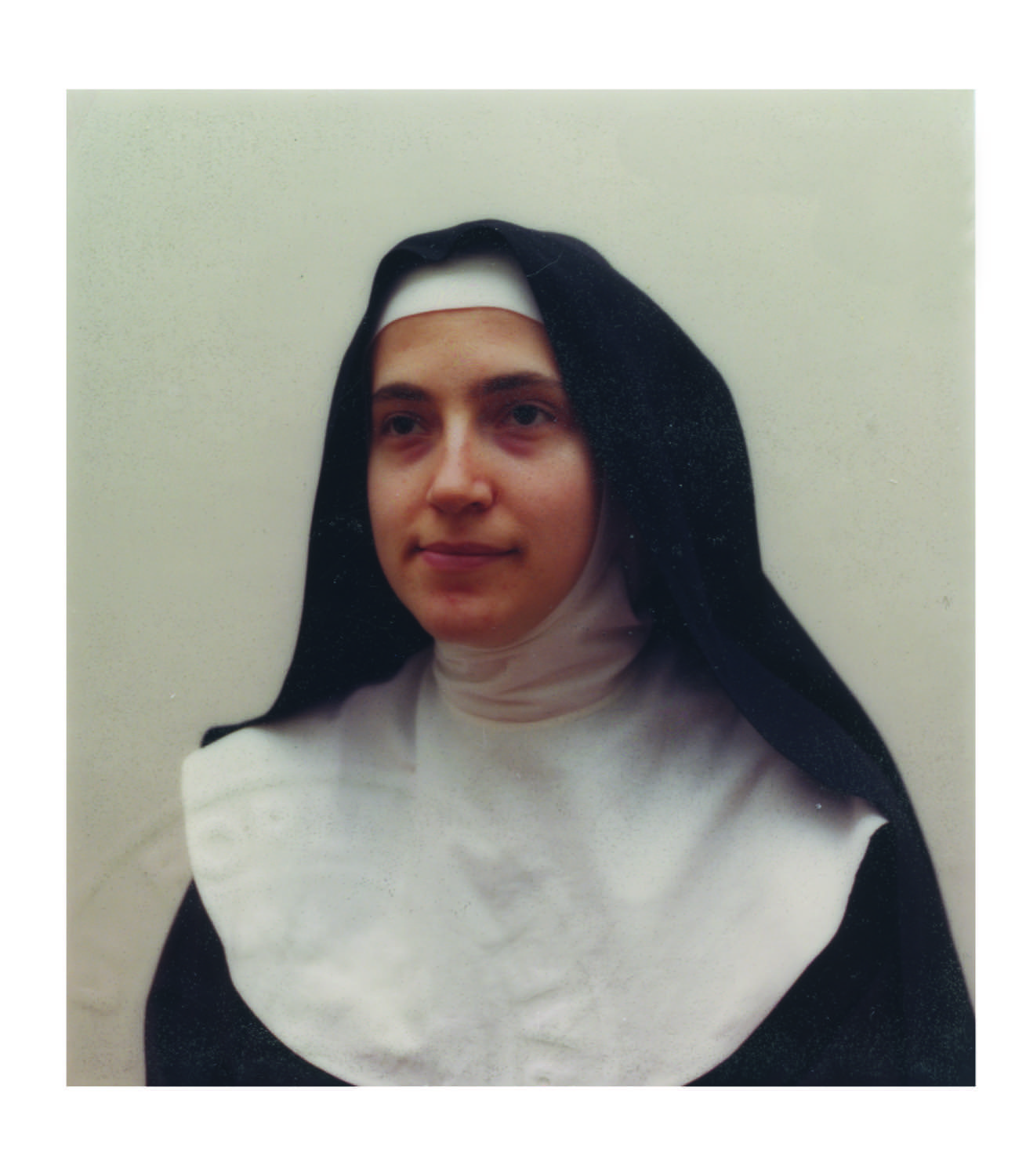

4th CHAPTER: RADICAL AS CONTEMPLATION

Ever since the Christian fathers took to retreating to the desert to pray around the IV century after Christ, contemplative solitude has represented a privileged path towards contact with God.

One of ist most radical forms is cloistering, still practiced today: nuns are not allowed to leave their convent except for a few limited circumstances, such a getting their passport picture taken. `The nuns posed in front of the lens as if their faces no longer belonged tot hem; and they came out perfectly,`wrote Calvino in The Watcher. `Not all of the of course (…), you had to cross a kind of threshold, forgetting yourself, and then the photograph recorded this immediacy, this inner peace and blessedness.`

Over the course of the centuries, the image of the veiled nun confined to her cell has become iconic of lived above mundane passions. `The truth is we pursue the most common aspect of the most common humanity,`writes Mother Ignazia Angelini, abbess of the Benedictine monastery of Viboldone, Milan. `The challenge ist o show we are different to other women, deeply subject to passions, deeply fallible, and deeply wounded.`

5th CHAPTER: RADICAL AS EVASION

The photgraphic portraits of this section were taken at rave parties, street parades and music festivals in Italy and around Europe, and then revisited with oil painting on paper. Immortalized at their most intimate and raw, the protagonists of these pictures evoke both compassion and condemnation, attraction and abjection, thus embodying the duality inherent in the verb „to rave“: to be delirious, to talk incoherently, but also tob e greatly enthused by someone or something.

Printed by LONGO