Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

Review: Gauri Gill – Acts of Appearance

Jun 05, 2018 - Lola Mac Dougall

Gauri Gill (Chandigarh, 1970) has often dealt with India’s rural and disenfranchised communities in her photographic practice. Her latest body of work – on view at MoMA PS1 from April 15 to September 3, 2018 – is no exception, with the caveat that the collaboration with her sitters appears to be getting more significant than ever in Acts of Appearance (2015-ongoing).

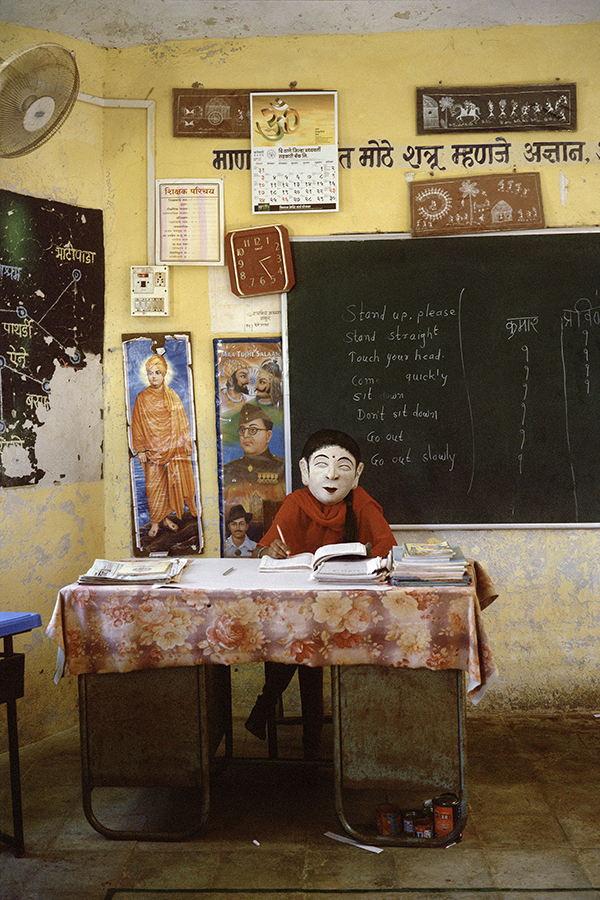

Gill’s work is probably one of India’s most notable examples of the so-called expressive documentary approach although she has developed her own personal aesthetic precisely by spanning a variety of photographic genres. During one of her trips to Maharashtra, Gill heard about the ritualistic Bahora masks, traditionally made in several local Adivasi villages by paper mache artists and used once a year in public processions to represent archetypes of gods, demons and other characters from Hindu and local tribal mythology. Gill traced one particular village which was home to accomplished craftsmen and commissioned them to produce a set of masks expressing, in contemporary forms and a new idiom, rasas (a Sanskrit term that refers to the emotions that govern human life), which become the focal point in this collection of remarkable portraits.

Gill is certainly not the first photographer to use masks to suggest the juxtaposition of a fantastic dimension with a tangible reality. This is a strategy we have seen quite often of late, as it offers an easy shortcut to move to the other side, the trendy realm of fictionalised documentary. But Gill is no follower of trends, and her use of the mask as an expressive tool is thoughtful and consistent with her previous explorations, characterised by a magical realism of sorts. These acts of ‘disappearance’, rather, afforded by the masks are to be seen in the context of earlier instances where she achieved a dreamlike mood by inserting objects or gestures that complicate a straightforward reading of the photographs as documents. In the Balika Mela series (2003-2010) simple props were given to the girls and young women who posed for Gill in an improvised photo studio and who used them to the maximum of their expressive capabilities. In Notes from the Desert – an extensive portfolio of interconnected photo series shot in rural Rajasthan from 1999 to the present – everyday objects such as eggs, a plastic bag or a mirror took on symbolic functions and defined the entire atmosphere of certain photographs.

In addition to her ability to evoke universal truths with minimum resources, what Gill’s use of the mask does, in this instance, is to bring in a unexpectedness of sorts that departs from the use of the prop as a mere gimmick. And she does so in bright light and in colour, in contrast to her recent bodies of work, restricted to black and white.

The masks, which were initially commissioned to embody emotions and experiences common to all human beings, but also animals which she understood to be a part of the universe of the community, soon incorporated, over extended dialogue with the artisans, objects of everyday use, as if they too were endowed with a soul. It must have been quite an experience for the photographer to be confronted with the unique masks representing the cell phone, the television and the mineral water bottle, and one can only celebrate her adaptability in incorporating them into the project. By welcoming the unexpected outcomes of the conversations, the invoked co-authorship with the craftsmen – who often become the sitters as well – is put to test and is no longer a mere rhetorical device. In fact, some of the most striking portraits are precisely those that portray human bodies with banal objects as heads, which can be read as an attempt to unmask their aspirations.

On occasion, quirky associations and dialogues are suggested, like the frog-fish couple in the window or the sun and moon walking towards us at dawn. Above all, the masks disrupt our expectations of what an adivasi (generic term that refers to indigenous people) village should look like. They have a two-fold liberating effect: firstly, they free the photographer from a literal depiction of the place and save her from having to justify the licence to look down the social scale. Secondly, they free us, the viewers, from the need to decipher the highly coded facial gestures of ‘the other’. At the same time, the occlusion brings to the fore elements that may have gone unnoticed otherwise: the landscape, the clothes and the bodies, whose language acquires an increased significance as a result of the denial of access to their faces. Nevertheless, we see them in their real environment, often looking straight into the camera while engrossed in a daily activity, affecting nonchalance in the school, the health centre, the shop, the building site. Are they characters? Are they human? Has Gill managed, yet again, to successfully subvert genres?

The masks, by liberating the sitters from their individuality, somehow manage to further humanise them. Perhaps the contemporary mythologies of their own invention – mundane rather than exceptional – that veil their faces convey their story in a more telling manner than any straightforward narrative might. It may well be that normalcy is better described through the anomalous. The work by Ralph Eugene Meatyard, who for thirteen years photographed his wife and friends masked in situations of feigned normalcy, comes to mind. Said Meatyard: “a mask serves to non-personalizing a person”. Through these acts of appearance, Gill comments on the universalizing power of masks and on their ability to metamorphose us into what we really are.

Lola Mac Dougall is the Founding Director of GoaPhoto and the Artistic Director of JaipurPhoto. She has a doctorate from Barcelona’s Pompeu Fabra University. Her thesis deals with Indian women photographers.