Specials

Specials is a virtual space dedicated to writing on photography, showcasing unique content, projects and announcements.

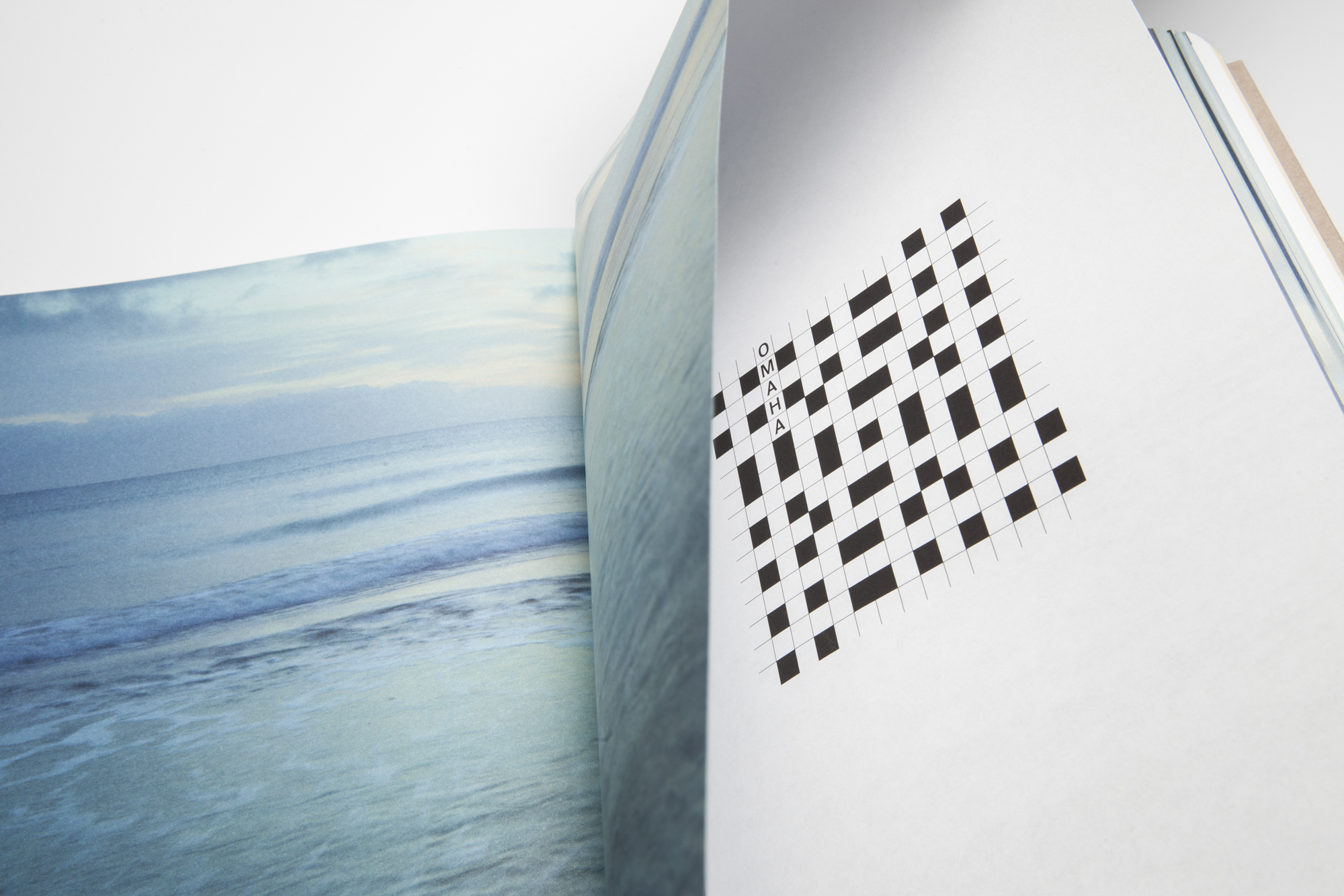

Special feature: WAR SAND by Donald Weber

Jun 21, 2018 - Gita Cooper-van Ingen

The seacoast of Normandy churns with history.

In this visionary collection of images, texts, and scientific data, photographer Donald Weber and his colleagues investigate the beaches of D-Day using the latest techniques of forensic analysis. What they find is something far larger than its microscopic constituents: War isn’t just a defining feature of our collective experience, but a quantum event, as well.

The war-relics presented here offer an immersive narrative on the theme of social memory. The assembled D-Day artifacts include WWII spy-craft and old Hollywood movies, dioramas and drone-mounted cameras, private post-war memoirs and wistful seaside photographs. They reveal our civilization’s longing for a final victory over death.

War Sand erodes the scale of reality at two levels, both elevating war into narratives and dissolving it into tiny fragments. When history ends, we are left only with a mysterious relationship between myth and micron.

My grandfather liked to tell stories about life and death, and the sea.

When I was 12, he told me the best sea-story I ever heard a fantastic tale about WWII. It was the first time I heard the word “commando.”

The story went like this.

During New Year’s 1943, nine British commandos were ordered to cross the English Channel and surface on the beaches of Normandy in France. On landing, they had to meet with members of the French Resistance. The mission was to covertly collect sand and soil samples along a vast stretch of coast, from Ouistreham in the east to Cherbourg in the west. They had two days and nights to cross the Channel, collect the samples, and return without being caught. France, and the seacoast in particular, was thick with German forces. The Atlantic Wall, Hitler’s dream fortress, was a wall of pure concrete, guarded by massed artillery and elite soldiers. To be caught meant certain execution as spies. They would swim under the sea, roam the beaches at midnight, and keep invisible. They would have black masks, rubber fins, wool turtlenecks, black Fairbairn-Sykes daggers with ring grips, Welrod silent pistols, and sampling tubes.

It was a perfect plan.

The British commandos would cross the Channel and complete their mission, swimming up the coast with the midnight tides. If the commandos made it back to Britain, the samples would undergo scrutiny by scientists, geologists and physicists. Supreme Allied Commander Eisenhower and Field Marshal Montgomery were counting on these minuscule grains of sand to withstand the weight of an invasion force, the largest the world had ever seen. Thousands of ships, soldiers and armaments would land on Normandy’s beaches for the liberation of Western Europe. But first, the commandos had to complete the mission.

At the end of his story, my grandfather opened a small wooden box, and unwrapped a small glass tube from a white linen cloth. It contained a pinchful of grey sand. “This is what we brought back.”

The staggering sacrifice of D-Day is well known. There were massive bombardments and huge losses of life, but there was fantastic and historical success, as well. Over 156,000 Allied soldiers penetrated German-occupied France on June 6, 1944, and stoutly held their positions on the beachhead despite furious counter-attacks by German divisions. Thousands of tons of ordnance exploded over the troops.

Today, this Allied and German war material survives as part of the natural sand grains of the Normandy beaches. Seventy years later, shrapnel, bullet casings, and crumbled armour plates persist in vast microscopic quantities. They have been transformed by sea waves and the sun’s heat into micro-artifacts that span the divide between technology and nature.

The invasion actually began with sand. Over New Year’s 1943-44, nine British commandos secretly crossed the English Channel in miniature submarines to collect sand samples. Their mission was to deliver these samples back to Allied geologists to test if Normandy’s shifting beaches could withstand the heavy war apparatus of the invasion force, the largest the world had ever seen. Their sand samples would determine the final Allied strategy – and fate of Western Europe.

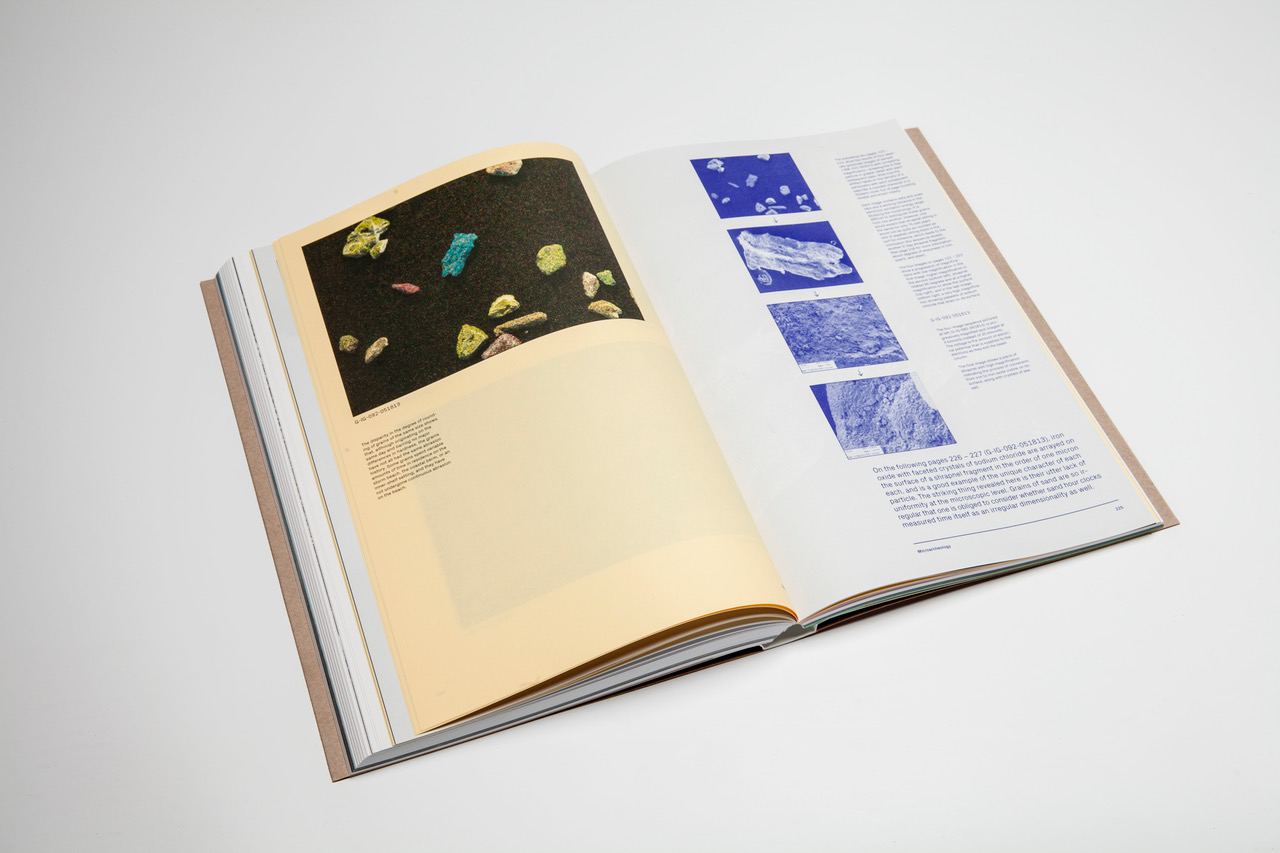

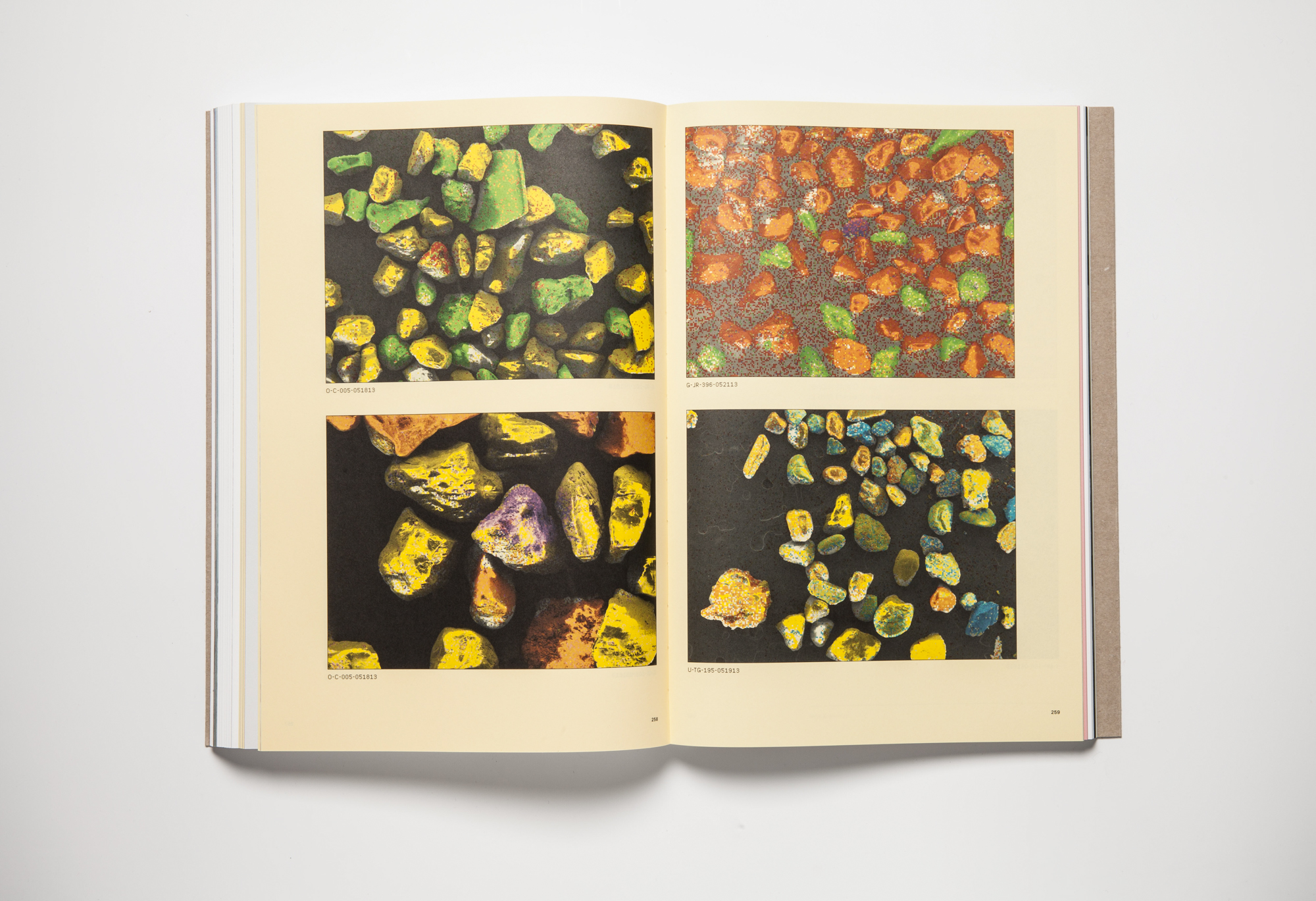

We start our analysis of the sand grains taken from the beaches of Normandy with a look at typical samples (O-DG-056-051813 & O-DG-033-051813) scooped by photographer Donald Weber. Seventy years ago, British commandos secretly excavated this fine sand for subsequent examination back in England with ordinary microscopes; 21st Century technical advances now allow us a much deeper look into this elemental crush. We have found that what survives is not just pretty interesting, but interestingly pretty.

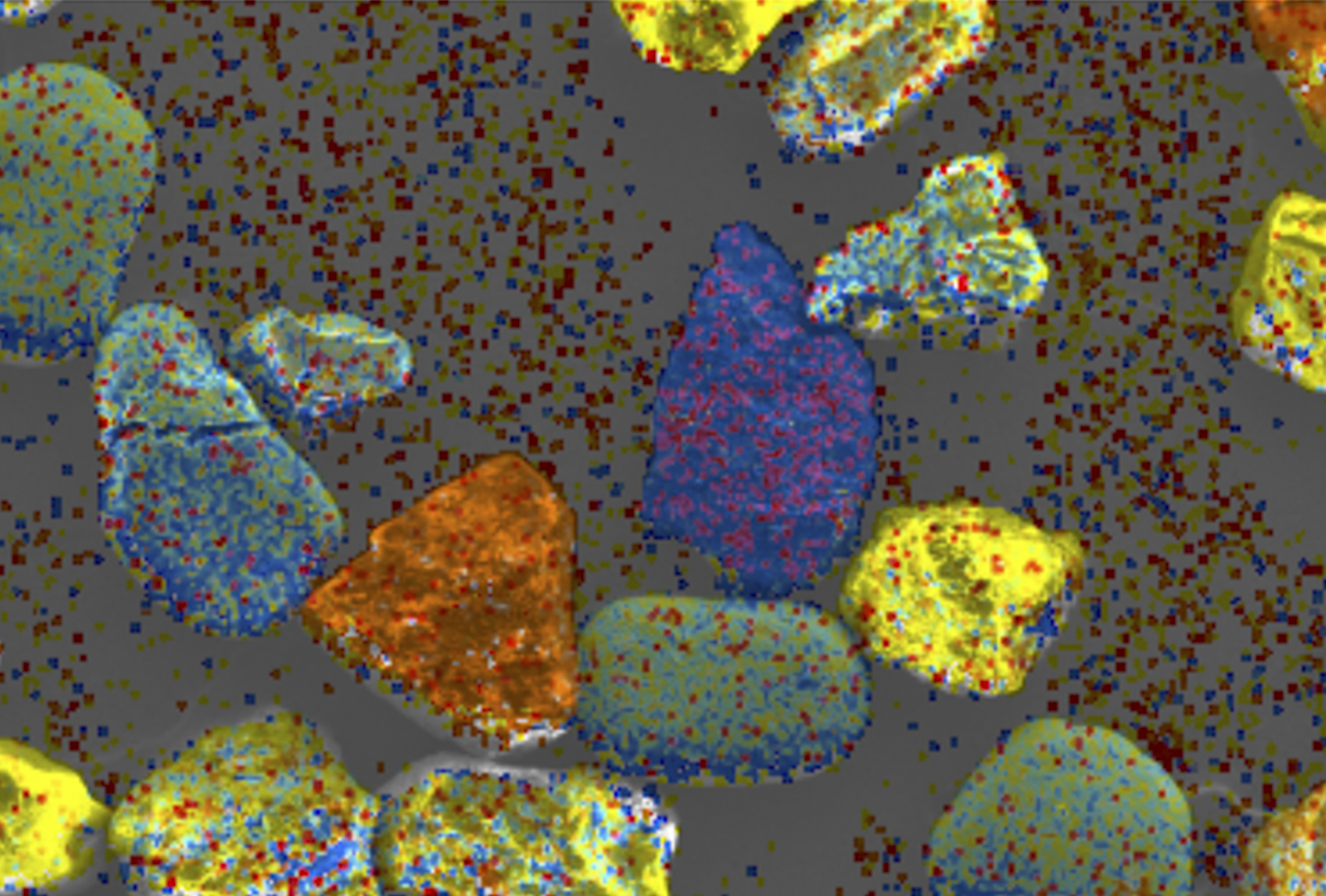

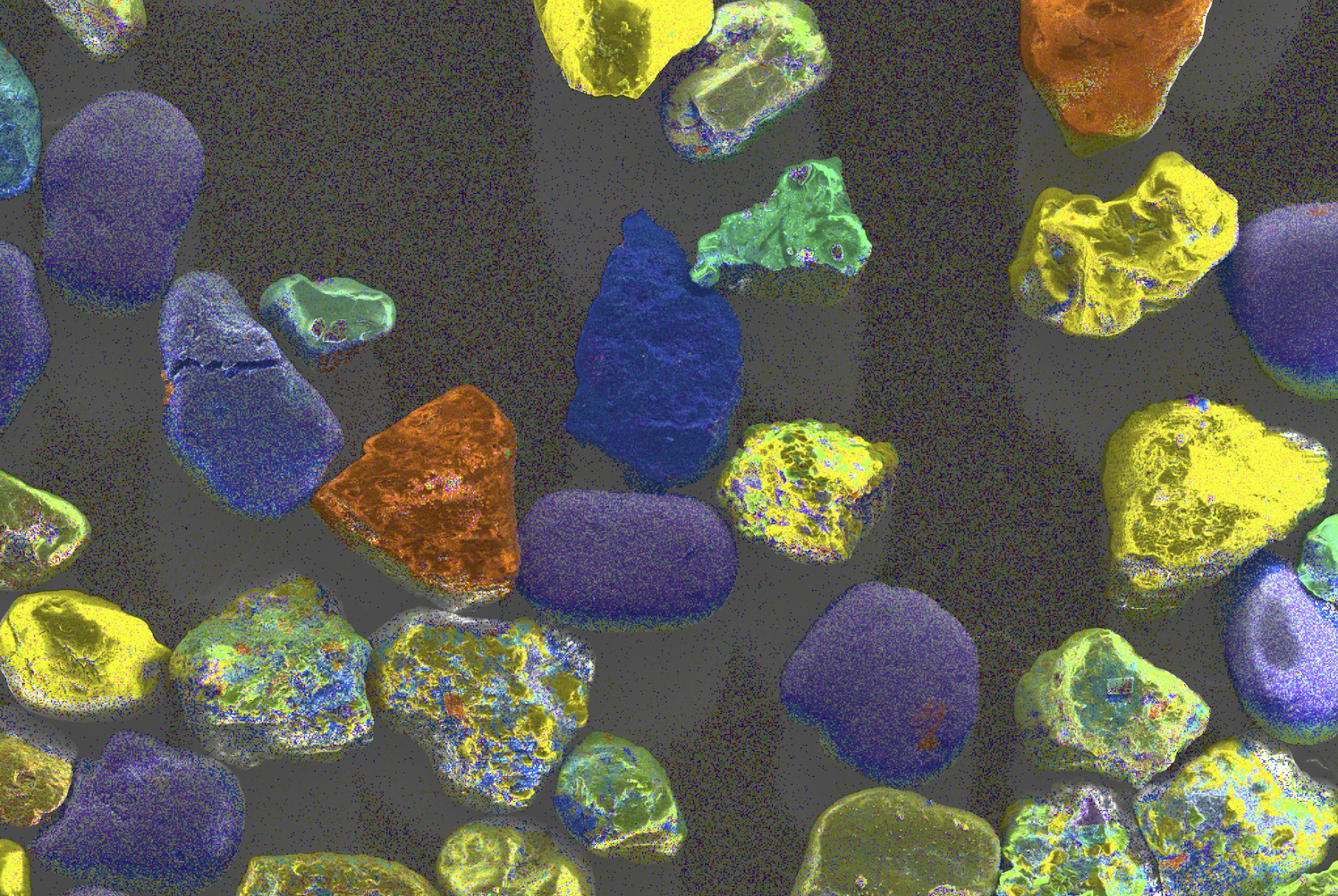

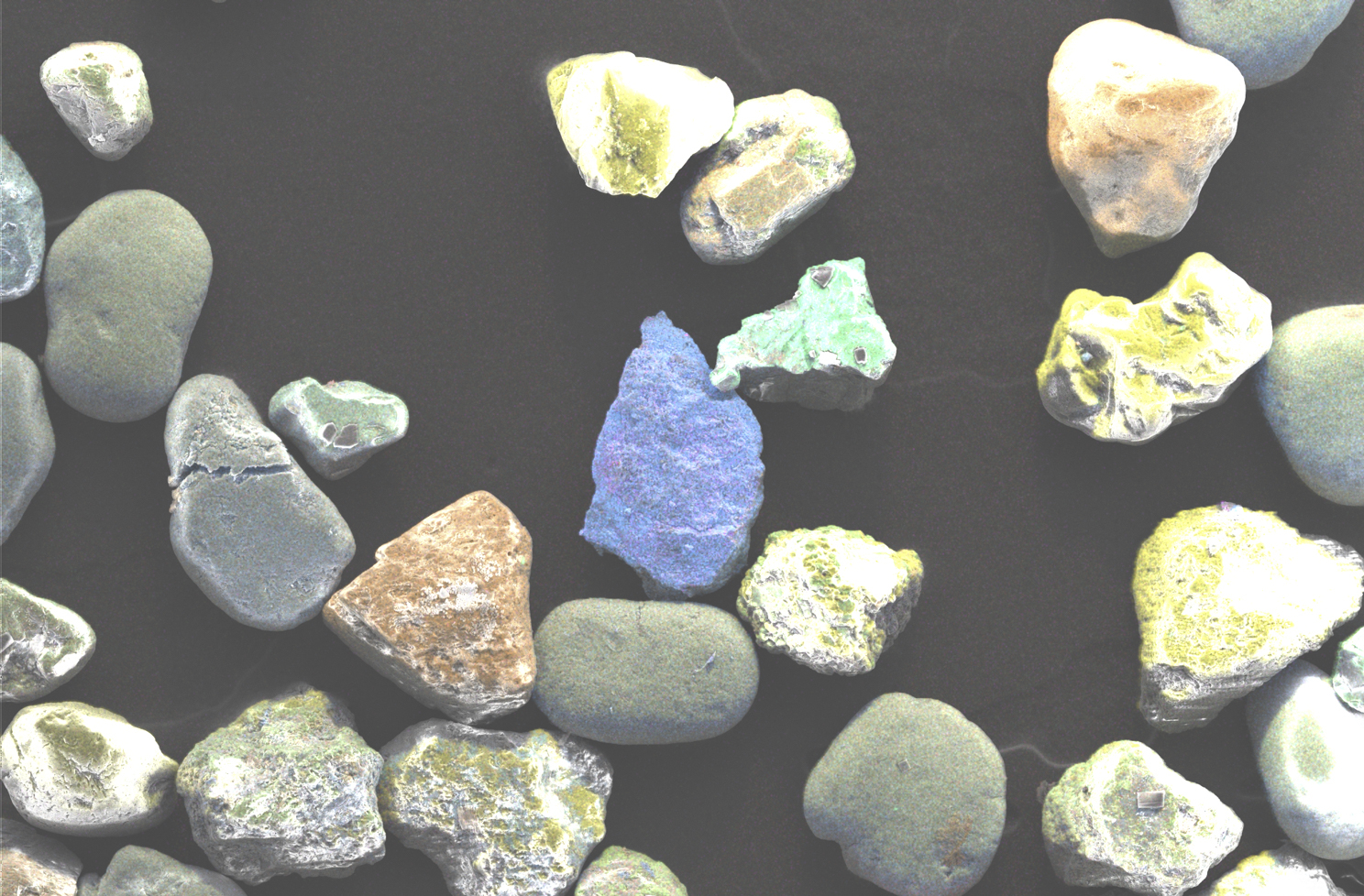

These three images are all from sample O-FG-423-052113 and show the rendering process from a low-resolution bitmap (upper left) to a high-resolution final image (bottom image).

The colour mappings present silicon (Si) as yellow, blue as iron (Fe), orange as calcium (Ca), and red for nickel (Ni), as well as were the final colours used in mapping. There are some naturally occurring nickel minerals in the sand, but moving to the larger image on this page, we find the higher resolution image produced by EDS that incontestably shows a D-day shrapnel particle, depicted in blue, in the very middle of the frame. The two smaller images on the left page are low-resolution bitmaps. A high-resolution image can take upwards of eight hours to render. You can see a key which displays the visible elements: red as nickel (Ni), orange as calcium (Ca), light blue as zinc (Zc), blue as iron (Fe), and yellow as silicon (Si).

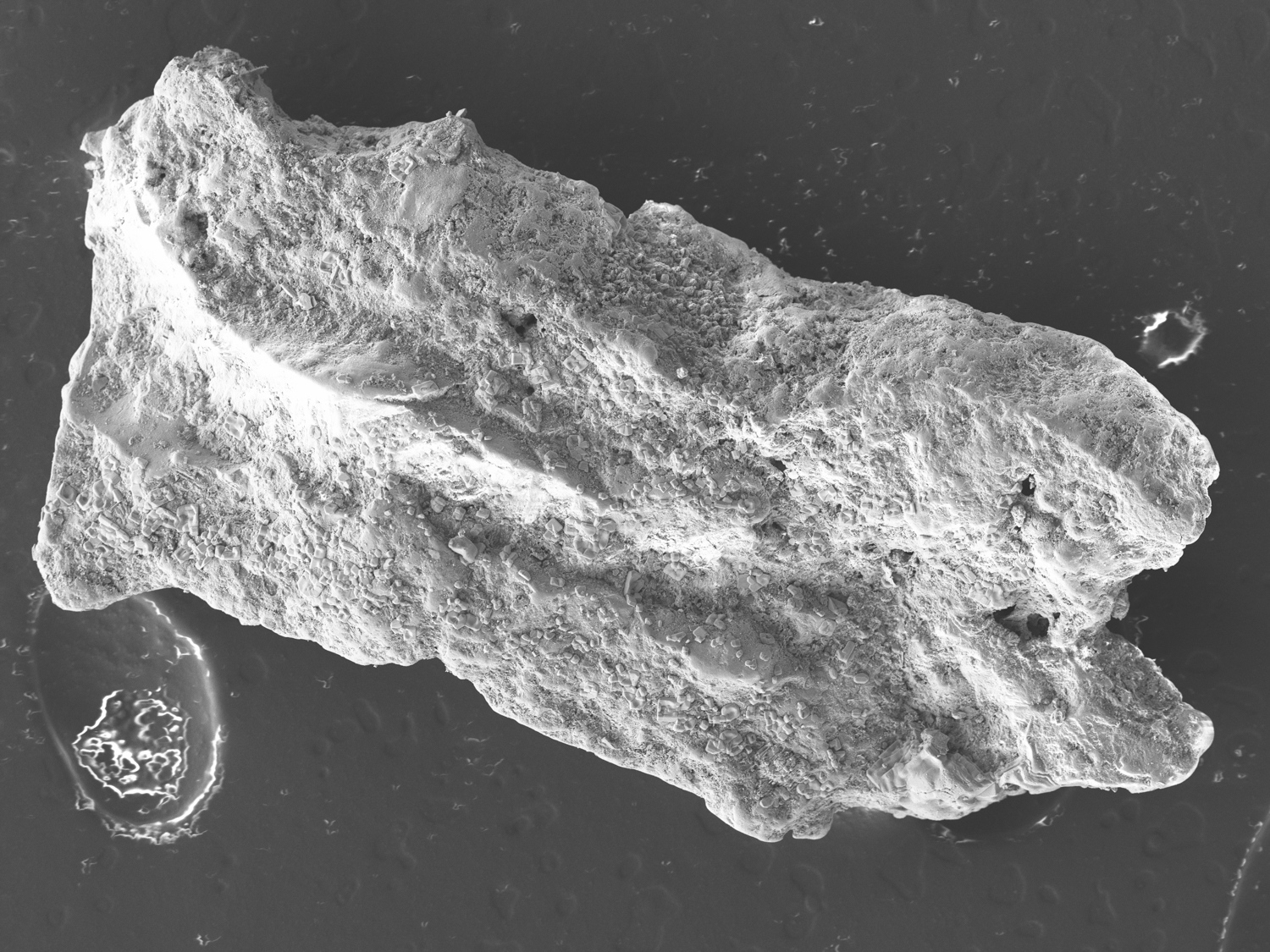

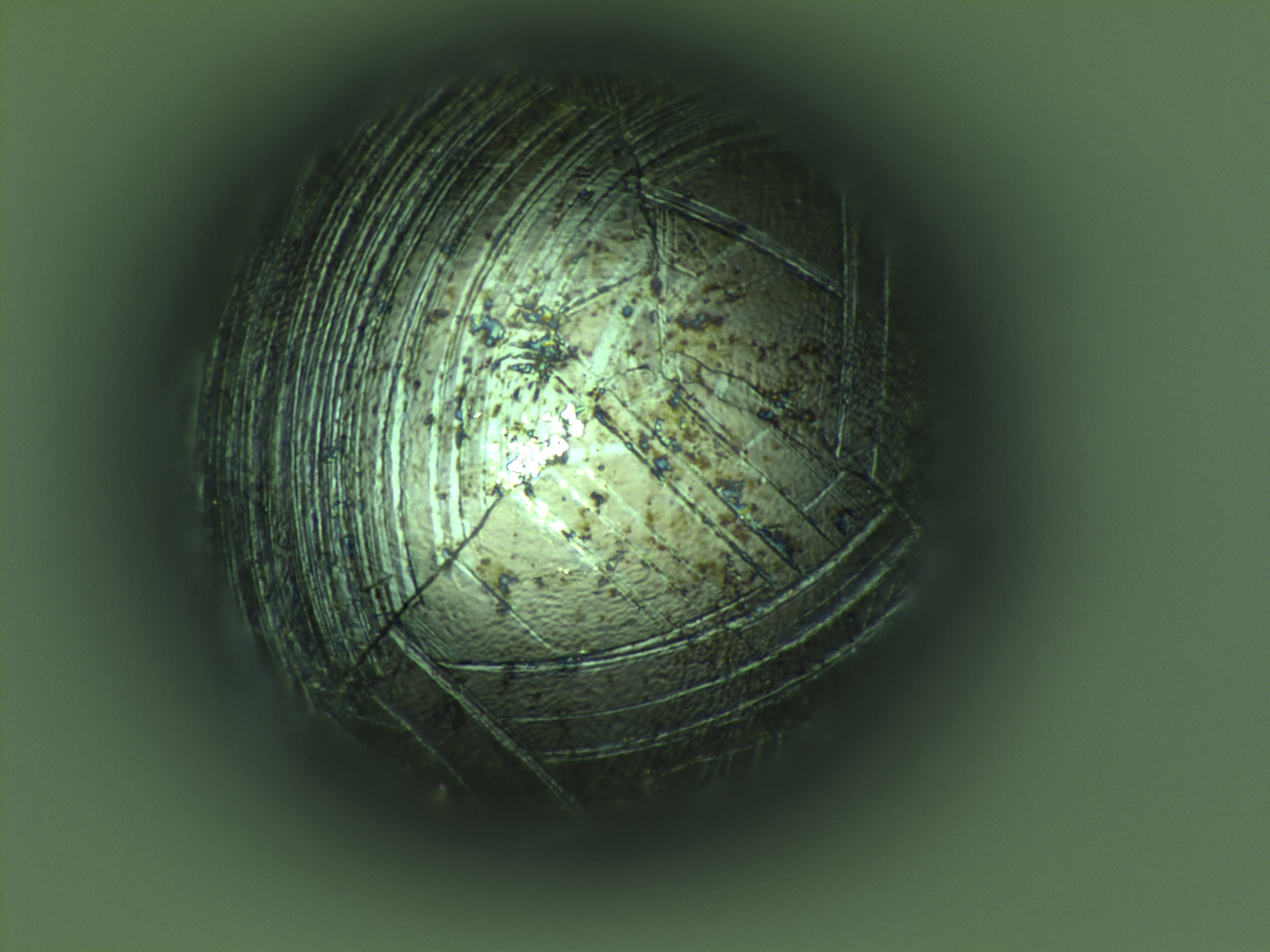

The image above shows iron oxide with faceted crystals of sodium chloride are arrayed on the surface of a shrapnel fragment in the order of one micron each, and is a good example of the unique character of each particle. The striking thing revealed here is their utter lack of uniformity at the microscopic level. Grains of sand are so irregular that one is obliged to consider whether sand hour clocks measured time itself as an irregular dimensionality as well.

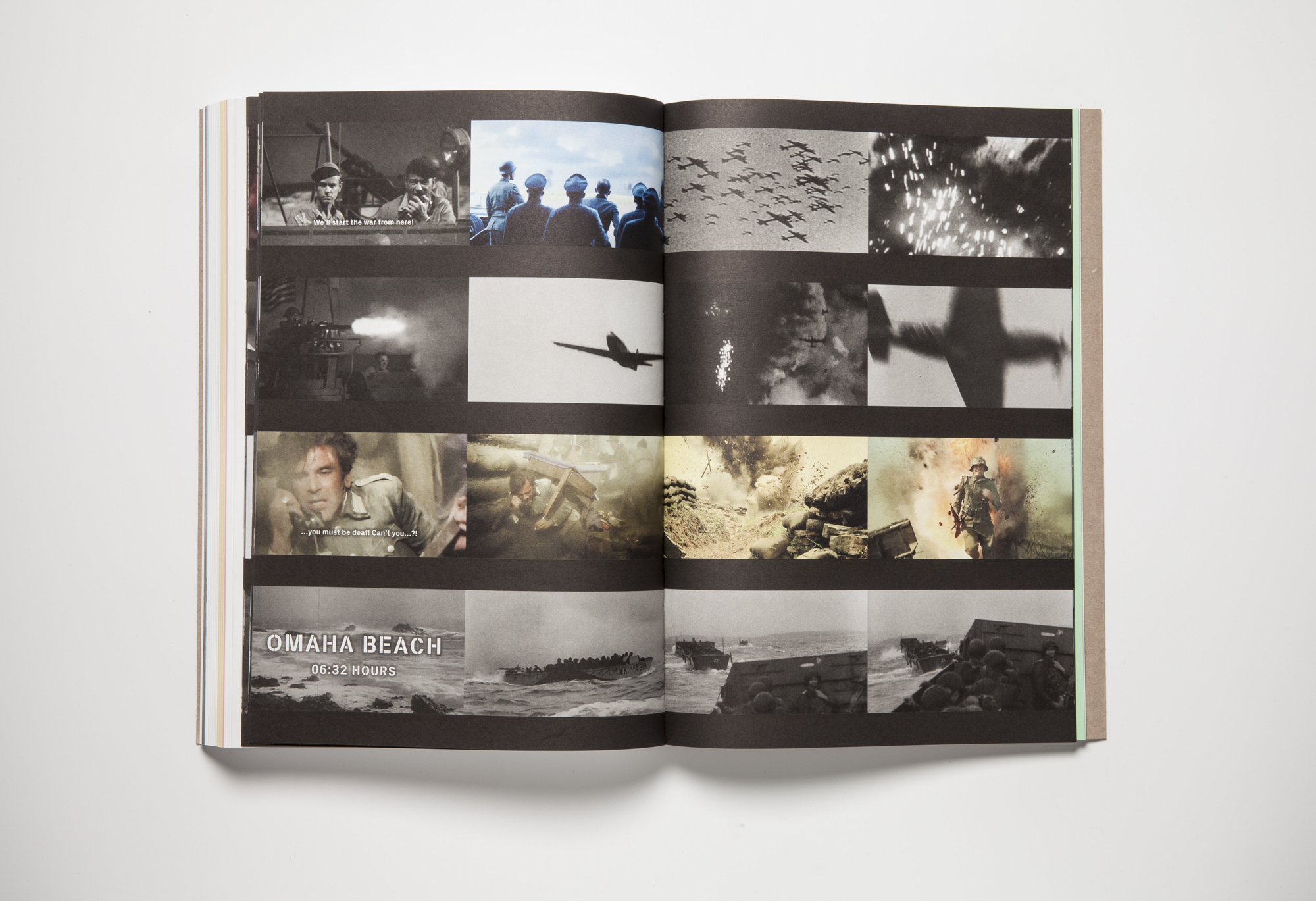

With the advent of the First World War, film has been integral in shaping the public consciousness of military events as they unfold and the public memory of wars after the guns have fallen silent. In Paul Virilio’s book War and Cinema, he traces what he calls the fusion/confusion of technologies of perception and of warfare, with the introduction of searchlights in the Russian-Japanese battle of Port Arthur in 1904. “These searchlights were war’s first projectors – they “illuminated a future where observation and destruction would develop at the same pace. Later the two would merge completely … above all [with] the blinding Hiroshima flash which literally photographed the shadow cast by beings and things, so that every surface immediately became the war’s recording surface, its film.”

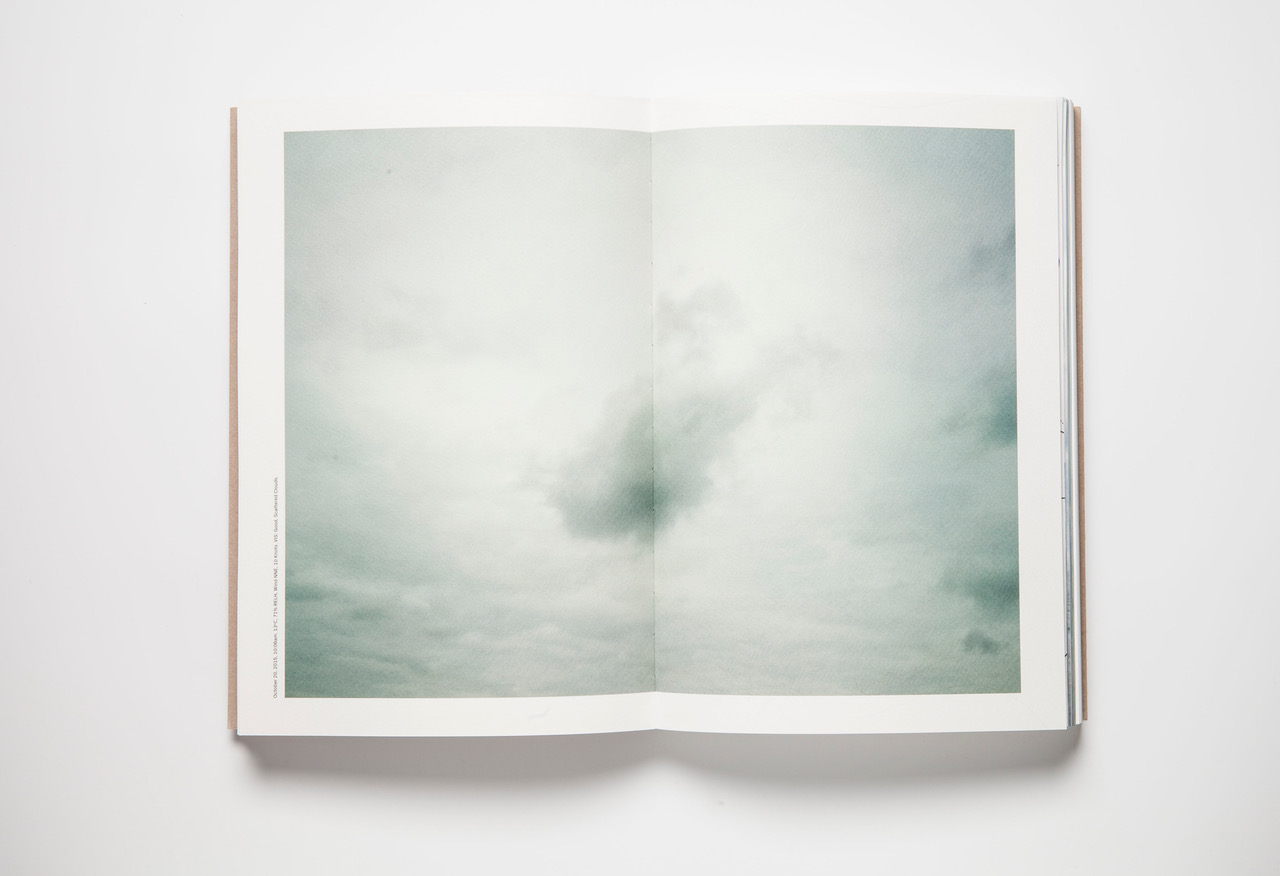

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of gravitational forces exerted by the moon, sun and rotation of the Earth. On D-Day, it was imperative for ground forces to land at low tide. German forecasters also predicted the stormy conditions that indeed rolled in as the Allies had feared. The Luftwaffe’s chief meteorologist, however, went further in reporting that rough seas and gale-force winds were unlikely to weaken until mid-June. Armed with that forecast, Nazi commanders thought it impossible that an Allied invasion was imminent, and many left their coastal defences to participate in nearby war games.

The invasion was originally scheduled for the morning of June 5. It was up to chief meteorologist James Stagg to advise Ike to postpone it by one day, despite protests from his fellow meteorologists, who felt the weather would be good enough for the mission to take place. However, the weather over Normandy had too much cloud cover, the winds were too strong and waves too high. The key element of surprise—location and time—would have been lost, and the conquest of Western Europe might have taken another year.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel believed that any invasion would come at high tide, when the beachhead was at its narrowest and troops would be vulnerable to German fire for the shortest period of time. He therefore devised a series of obstacles adapted for use under water that would be completely concealed during mid and high tides. The jagged edges of iron ‘hedgehogs’ could tear through the bottom of landing craft.

It must be evident to readers by now that the soldiers of D-Day would have, in addition to everything else they endured, also suffered what can be thought of as micro-injuries as a result of weaponized matter bursting into smaller, microscopic fragments and penetrating the flesh.

In all, over 425,000 Allied and German troops were killed, wounded or went missing during the Battle of Normandy. This figure includes over 209,000 Allied casualties, with nearly 37,000 dead among ground forces and a further 16,714 deaths among Allied air forces. Of Allied casualties, 83,045 were from 21st Army Group (British, Canadian, and Polish ground forces) and 125,847 from the U.S. ground forces. The losses of the German forces during the Battle of Normandy can only be estimated. Roughly 200,000 German troops were killed or wounded. The Allies also captured 200,000 prisoners of war (not included in the 425,000 total mentioned above). During the battle, between 15,000 and 20,000 French civilians were killed, mainly as a result of Allied bombing. Thousands more fled their homes to escape the fighting. Today, 27 war cemeteries hold the remains of over 110,000 dead from both sides: 77,866 German, 9,386 American, 17,769 British, 5,002 Canadian and 650 Poles.

In scientific literature, the image (J-MR-172-051813) with this shape and containing scratches on the surface is called a “microsphereule,” composed primarily of iron and nickel (perhaps 5% nickel), and caused by high-heat detonations. Microscopic spherical particles created through a physicochemical process with each sphere containing an equilibrium of forces with a fluid medium, such as water or air. Some microspherules may take the shape of pisolites, chondrules, biolites, pellets, bubbles, and carbonaceous microspherules. Usually, they are the result of meteorites exploding in the earth’s upper atmosphere, however, in this case, it is more than likely the result of an artillery blast. The molten metal solidifies in the air, and surface tension pulls it into a spheroid shaped like raindrops.

Swash

Known as forewash in geography, it is the turbulent layer of water that washes up on a beach after an incoming wave has broken. Swash action can move beach materials up and down the beach, creating cross-shore sediment exchange. The swash motion plays the primary role in the formation of morphological features and their changes in the swash zone and contributes to geological processes in coastal morphodynamics.

Wartime sacrifice on the beaches of Normandy in 1944 is History: massive casualties, but great success. Allied soldiers, numbering in total over 156,000, penetrated into German-occupied France on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and stoutly held their positions despite repeated counter-attacks by German divisions. But where does memory end and History begin?

Donald Weber’s War Sand is a powerful and poetic rumination on historical decay. It examines the evidence that D-Day actually took place; it explores the tidal processes of human memory, and considers the terror of war in its undying timelessness.

In June of 2013, Weber walked the beaches of coastal Normandy, the same month of the Allied invasion, collecting hundreds of sand samples from each of the five D-Day landing beaches (Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword). “I got the idea for the project from my grandfather, a veteran,” Weber says. “He told stories of British frogmen coming up from the sea at midnight to scoop beach samples from the Normandy coast. All very hush-hush, it was a secret investigation that was a prelude to the invasion. I decided to continue this story and collect my own sand samples to analyze.” Weber sent his samples back to Canada. Utilizing the new science of microarcheology, the sand was studied under a powerful scanning electron microscope (SEM) at the Queen’s University Physics Department by Dr. Kevin Robbie. What the microscope revealed, hidden amongst the natural sand grains, were tiny traces of Allied and German war material, evidence that, yes, something cataclysmic had occurred at these sites. Fragments of human bone, brass, steel, titanium, and iron are still there, some 70 years later, transformed by the action of the sea waves and the sun’s heat into an array of micro-artifacts that span the divide between technology and nature. While most are oblivious to the fact, Weber and Robbie estimate that as much as 5 per cent of the sand content of these beaches today is made up of shrapnel and detritus from that fateful day in June.

What does this gritty sand tell us? It becomes a speculation, a matter of interpretation of history, and a marker of time. Like the ocean, human memory is protean. It erodes the scale of reality at two levels, both elevating war into narratives and dissolving it into tiny fragments. When history ends we are left only with a mysterious relationship between myth and micron.

Later in 2013, Weber returned and for the next three years photographed the beaches as they are today, taking in all views (looking out, up, down, and back). He gives us a spectacular array of undulating seascapes and moody landscapes; corroded pillboxes and monuments, seaside towns and beaches; and ever shifting images of the weather and clouds. In addition to the micro-artifacts, Weber incorporates a drone to take aerial macro-images of Normandy’s battle beaches. As he explains: “The resulting images of foggy seascapes and odd wave formations suggest an opposition between unreachable infinity, and the stories we locate in this unknowable setting. Here, at last, the edge. The place of final opposition between matter and idea, meaning and noise, pattern and silence. This littoral edge is the line where War Sand has invested all its efforts.”

The Standard Model of physics gives us particles, frenetic and disparate. Einstein’s Relativity Model offers the elegance of universality and its laws. Facts and interpretation. Neither model confronts the open sea as Weber’s poetic large-scale sea-photos aim to do. The open water, the open question. The limitless sky above the seawater plays with erasure and entrance. The cloud photos both veil fate and suggest the possibility of rapture. That is, if we care to contemplate such things.

War Sand gazes unflinchingly at that which is. The view takes in children playing on the beach in summer, a simulacrum of the cyclical combat harking back to the Normans, and before them, the Vikings, and before them, and them. That which is always there – immanent, unceasing – is the real subject of Weber’s War Sand. At its very core lie questions of truth (historical, experiential, material) and our ability to know anything of it.

War Sand:

Publisher: Polygon, 2018

Paperback: 372 pp., fold-out map insert, 195+ colour and B&W images

Dimensions: 7.6×11.4″ (195×290 mm)

Language: English, French and German

ISBN: 978-0-9959377-0-3

Photography by Donald Weber

Text by Larry Frolick, Kevin Robbie and Donald Weber

Design by Teun van der Heijden

The book is available here.